Jill Richardson: Whites should consider what it's like being black

Via OtherWords.org

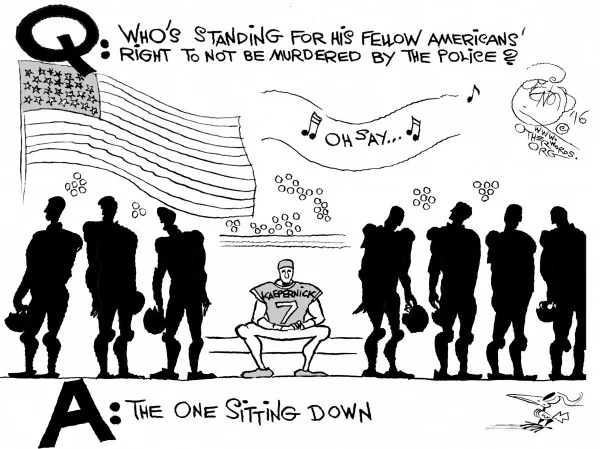

As white people across the nation criticize Colin Kaepernick and other NFL players who “take a knee” for the national anthem, they ought to know something first.

White people in America have no idea what life is like for black people in America.

How can I make such a broad statement? How would I possibly know?

For one thing, I’m white. I grew up in a mostly white town. Like many white people, I was raised to oppose racism, at least as I understood it then. I celebrated Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr.

I wasn’t quite sure who Malcolm X was — I’d heard the name, but we never studied him in school. I’d never heard of other black leaders like Marcus Garvey or Bayard Rustin.

I never used the N-word. I wouldn’t even write it in my essay on Huckleberry Finn in ninth grade English. And I’d never even heard of most other racial slurs for African Americans — or any other race for that matter. Nobody used language like that.

But that was the extent of my background when, three years ago, I found myself assigned to be a teaching assistant in a sociology class on race. The professor would give the lectures; I would lead the discussions.

To say it was terrifying is an understatement. I didn’t know any of the material I now had to teach, and I was flying by the seat of my pants.

Fortunately, I did know how to listen. And I know how to empathize.

In the years since, I’ve taught hundreds of students of all races — first as a teaching assistant and now as an adjunct professor.

And it’s funny. When you start listening, you learn things.

I learned that being black in America means people who aren’t black think it’s OK to touch your hair whenever they want — often without asking, even if they don’t know you.

When my students inadvertently made racist remarks, it didn’t hurt me as a white person. If I weren’t white, it would’ve stung. And I would’ve had to remain cool and professional while continuing to do my job — something I learned nonwhite people have to do all the time.

I learned that decades of housing discrimination robbed black people of wealth as most whites bought homes and built equity. The effects of those disparities live on.

Long after segregation was legal, we continue to live in racially segregated neighborhoods, and students like Michael Brown attend schools so poor I couldn’t even fathom that such a place would be called a school.

How can anyone succeed in college or find a good job if they barely even have one class a day where a teacher shows up and teaches using, as was the case in a district detailed in a 2015, This American Life, the NPR show?

Each year, I face the same conundrum: My students inhabit different worlds. The white students think that they know all there is to know about life in America. My job is to gently show them they have no idea — as I had no idea — what it’s like not to be white in America.

I can’t speak for black people, and I wouldn’t try to. They speak very well for themselves. I’ll just say that those of us who are white should listen when they do.

And to do that, white people must overcome their defensiveness. Not every protest against racism is a personal attack against them, the flag, the country, or whatever else.

So if you’re white, next time you see black football players take a knee and don’t understand, take it as a sign you have something to learn.

Jill Richardson is an OtherWords,org columnist.

Chris Powell: He won't stand for the country that made him rich

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Good for President Obama for acknowledging that the quarterback of the San Francisco 49ers has a right to protest racial injustice by refusing to stand when the national anthem is played.

Thanks to a heroic decision of the Supreme Court during World War II, schoolchildren also have the right to refuse to salute the flag in class -- a right that actually proclaims the flag to be the flag most worth saluting.

But the quarterback, Colin Kaepernick, isn't necessarily persuasive. For of course the country isn't and never will be perfect; it will always be full of legitimate grievances, like Kaepernick's -- recent shootings of black people by police officers, several of which, captured on cellphone video, seem murderous.

The key questions are whether such shootings are policy or aberrations and whether the country remains worth supporting for its ideals and the rights it bestows on everyone -- worth supporting for its objectives of "liberty and justice for all."

"I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color," Kaepernick said last month. "To me this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder."

But "people getting paid leave" is only a matter of due process of law while they are being investigated. Further, since the criminal-justice system will always be imperfect, either because its participants are fallible or because proof is not always available, some people will always be "getting away with murder." They're not all white police officers. Some are black, like O.J. Simpson.

Kaepernick is black, and if this country is really so oppressive to black people, why does he stay? Obviously the country is not so oppressive to him, as he is being paid $114 million under a six-year contract with the 49ers, wealth that casts an ironic sheen on his indignation. That's because his own well-earned success, duplicated by many other members of minority groups, is no aberration. National policy, flawed as it may be, is to facilitate it.

Exercising them as he has done, Kaepernick at least has reminded people of their constitutional rights and thus of the country's greatness. But he still may be rebuked, since, as Robert Frost wrote:

No one of honest feeling would approve

A ruler who pretended not to love

A turbulence he had the better of.

INDIGNATION INDUSTRY IS ASKING FOR IT: Years ago the comedian Steve Martin apologized facetiously to the National Association of Colored People "for referring to its members as ‘colored people.'" The other day a host of ABC's Good Morning, America, Amy Robach, apologized seriously for having said "colored people" on the air in a report about casting practices in the movie industry.

For reasons that aren't clear, it is OK for the NAACP to perpetuate the phrase but insulting if not racist for anyone else to use it. It's also OK to say "people of color."

So what's the difference? Only fashion.

Robach may have been unaware of that fashion and she plainly meant no harm, but she was quickly condemned on "social media" and was intimidated. So she issued a statement calling her choice of words "a mistake" and "not a reflection of how I feel or speak in my everyday life," adding that she had intended to say "people of color."

The indignation industry may snicker at all the innocents it is intimidating, but if it wants to understand what has given rise to Donald Trump and other forms of angry reaction in politics and public life, it needs only to look in the mirror.

Chris Powell, an essayist on social, political and economic maters, is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.