Scott Taylor: The mystic and the mathematician

The Babylonian mathematical tablet, dated to 1800 B.C.

‘Waterville, Maine

Like most mathematicians, I hear confessions from complete strangers: the inevitable “I was always bad at math.” I suppress the response, “You are forgiven, my child.”

Why does it feel like a sin to struggle in math? Why are so many traumatized by their mathematics education? Is learning math worthwhile?

Sometimes agreeing and sometimes disagreeing, André and Simone Weil were the sort of siblings who would argue about such questions. André achieved renown as a mathematician; Simone was a formidable philosopher and mystic. André focused on applying algebra and geometry to deep questions about the structures of whole numbers, while Simone was concerned with how the world can be soul-crushing.

Both wrestled with the best way to teach math. Their insights and contradictions point to the fundamental role that mathematics and mathematics education play in human life and culture.

André Weil’s rigorous mathematics

André Weil, pictured here in 1956, was a prominent mathematician in the 20th century. Konrad Jacobs via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Unlike the prominent French mathematicians of previous generations, André, who was born in 1906 and died in 1998, spent little time philosophizing. For him, mathematics was a living subject endowed with a long and substantial history, but as he remarked, he saw “no need to defend (it).”

In his interactions with people, André was an unsparing critic. Although admired by some colleagues, he was feared by and at times disdainful of his students. He co-founded the Bourbaki mathematics collective that used abstraction and logical rigor to restructure mathematics from the ground up.

Nicolas Bourbaki’s commitment to proceeding from first principles, however, did not completely encapsulate his conception of what constituted worthwhile mathematics. André was attuned to how math should be taught differently to different audiences.

Tempering the Bourbaki spirit, he defined rigor as “(not) proving everything, but … endeavoring to assume as little as possible at every stage.”

The Bourbaki congress in 1938. Simone, pictured at front left, accompanies André, obscured at back left. Unknown author via Wikimedia Commons

In other words, absolute rigor has its place, but teachers must be willing to take their audience into account. He believed that teachers must motivate students by providing them meaningful problems and provocative examples. Excitement for advanced students comes in encountering the unknown; for beginning students, it emerges from solving questions of, as he put it, “theoretical or practical importance.” He insisted that math “must be a source of intellectual excitement.”

André’s own sense of intellectual excitement came from applying insights from one part of mathematics to other parts. In a letter to his sister, André described his work as seeking a metaphorical “Rosetta stone” of analogies between advanced versions of three basic mathematical objects: numbers, polynomials and geometric spaces.

André described mathematics in romantic terms. Initially, the relationship between the different parts of mathematics is that of passionate lovers, exchanging “furtive caresses” and having “inexplicable quarrels.” But as the analogies eventually give way to a single unified theory, the affair grows cold: “Gone is the analogy: gone are the two theories, their conflicts and their delicious reciprocal reflections … alas, all is just one theory, whose majestic beauty can no longer excite us.”

Despite being passionless, this theory that unifies numbers, polynomials and geometry gets to the heart of mathematics; André pursued it intensely. In the words of a colleague, André sought the “real meaning of every basic mathematical phenomenon.” For him, unlike his sister, this real meaning was found in the careful definitions, precisely articulated theorems and rigorous proofs of the most advanced mathematics of his time. Romantic language simply described the emotions of the mathematician encountering the mathematics; it did not point to any deeper significance.

Simone Weil and the philosophy of mathematics

On the other hand, Simone, who was born three years after André and died 55 years before him, used philosophy and religion to investigate the value of mathematics for nongeniuses, in addition to her work on politics, war, science and suffering.

Simone Weil, pictured here in 1925, was a prominent philosopher. Anonymous via Wikimedia Commons

All of her writing – indeed, her life – has a maddening quality to it. In her polished essays, as well as her private letters and journals, she will often make an extreme assertion or enigmatic comment. Such assertions might concern the motivations of scientists, the psychological state of a sufferer, the nature of labor, an analysis of labor unions or an interpretation of Greek philosophers and mathematicians. She is not a systematic thinker but rather circles around and around clusters of ideas and themes. When I read her writing, I am often taken aback. I start to argue with her, bringing up counterexamples and qualifications, but I eventually end up granting the essence of her point. Simone was known for the single-minded pursuit of her ideals.

Despite the discomfort her viewpoints provoke, they are worth engaging. Although her childhood was largely happy, her whole life she felt stupid in comparison with her brother. She channeled her feelings of inadequacy into an exploration of how to experience a meaningful existence in the face of oppression and affliction. Over her life, she developed an interpretation of beauty and suffering intertwined with geometry.

Along with her lifelong mathematical discussions with André, her views were influenced by one of her first jobs as a teacher. In a letter to a colleague, she described her pupils as struggling because they “regarded the various sciences as compilations of cut-and-dried knowledge.” Like André, Simone saw the ability to motivate students as the key to good teaching. She taught mathematics as a subject embedded in culture, emphasizing overarching historical themes. Even those students who were “most ignorant in science” followed her lectures with “passionate interest.”

For Simone, however, the primary purpose of mathematics education was to develop the virtue of attention. Mathematics confronts us with our mistakes, and the contemplation of these inadequacies brings the ability to concentrate on one thing, at the exclusion of all else, to the fore. As a math teacher, I frequently see students grit their teeth and furrow their brow, developing only a headache and resentment. According to Simone, however, true attention arises from joy and desire. We hold our knowledge lightly and wait with detached thought for light to arrive.

For Simone, the “first duty” of teachers is to help students develop, through their studies, the ability to apprehend God, which she conceptualized as a blending of Plato’s description of the ultimate Good with Christian conceptions of the self-abnegating God. A true understanding of God results in love for the afflicted.

Simone might even locate the lingering anxiety and frustration of many former math students in the absence of attention paid to them by their teachers.

Authors grapple with the Weil legacy

Recently, others have wrestled with the Weil legacy.

Sylvie Weil, André’s daughter, was born shortly before Simone’s death. Her family experience was that of being mistaken for her aunt, ignored or demeaned by her father and not being acknowledged and appreciated by those in her orbit.

Similarly, author Karen Olsson uses Simone and André to explore her own conflicted relationship with mathematics. Her forlorn quest to understand André’s mathematics eerily reflects Simone’s desire to understand André’s work and Sylvie’s desire to be seen as her own person, to not be in Simone’s shadow. Olsson studied with exceptional math teachers and students, all the while feeling out of place, overwhelmed and intimidated by her fellow students. Most painfully, in the process of writing her book on the Weil siblings, Olsson asks a mathematician, who had been a student with her, for help in understanding some aspect of André’s mathematics. She was ignored. Both Sylvie Weil and Karen Olsson are living witnesses to Simone’s observation that each of us cries out to be seen.

Christopher Jackson, on the other hand, gives testimony to how mathematics can live up to Simone’s vision. Jackson is incarcerated in a federal prison but found a new life through mathematics. His correspondence with mathematician Francis Su is the backbone of Su’s 2020 book “Mathematics for Human Flourishing,” which uses Simone’s observation that “every being cries out silently to be read differently” as a leitmotif. Su identifies aspects of mathematics that promote human flourishing, such as beauty, truth, freedom and love. In their own ways, both Simone and André would likely agree.

Scott Taylor is a professor of mathematics at Colby College in Waterville, Maine.

Disclosure statement

He receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the John and Mary Neff Foundation.

Cloudy at Colby

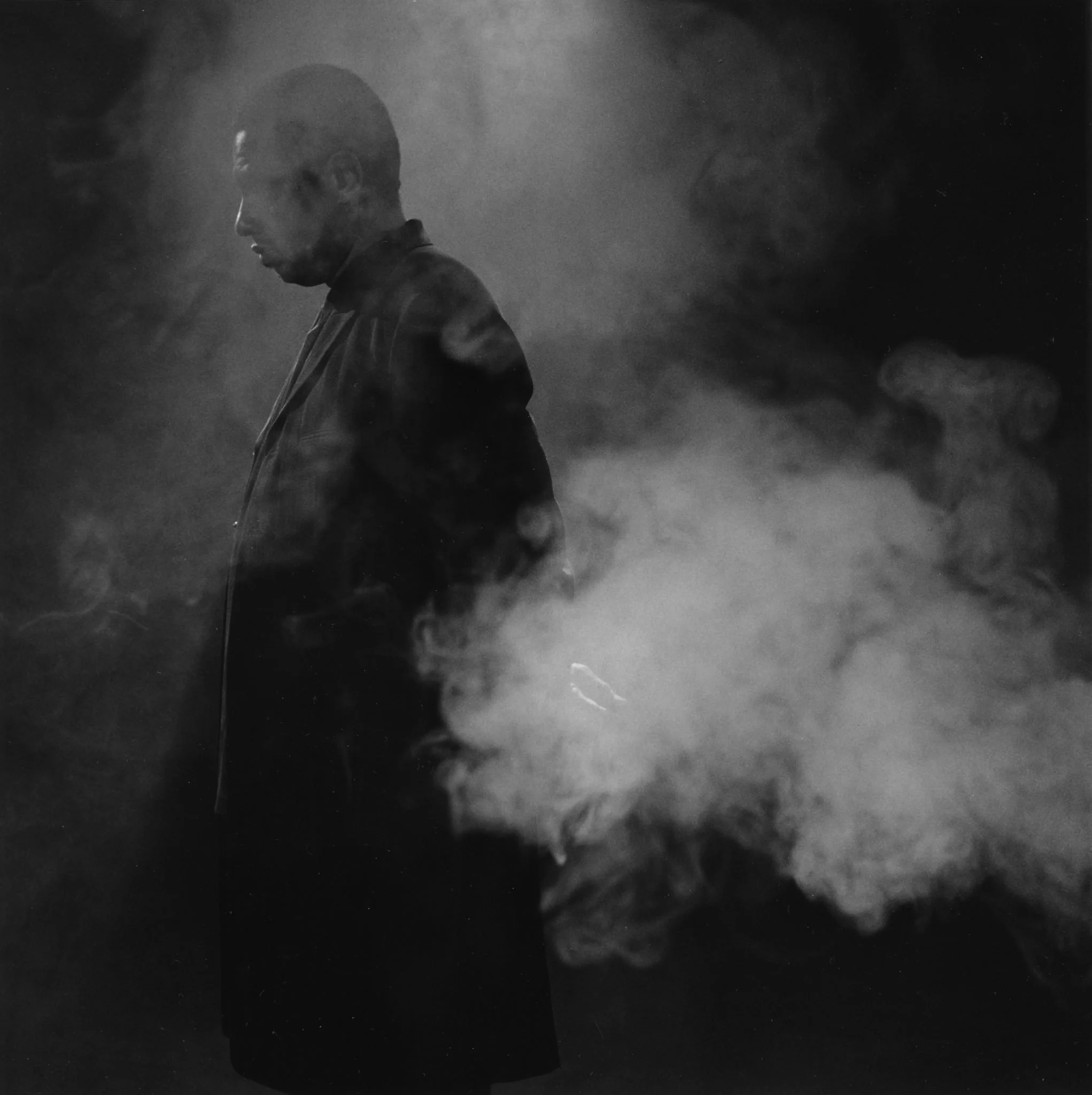

“Cloudscape’’ (still, video, sound), by Lorna Simpson, in the show “The Poetics of Atmosphere: Lorna Simpson’s ‘Cloudscape’ and Other Works from The Collection,’’ at the (surprisingly large) Colby College Museum, Waterville, Maine, Feb 3.-April 17.

The museum says:

“Simpson’s work examines how identity, specifically Black identity, is formed, perceived, and experienced. ‘Cloudscape’ features a singular figure, the artist Terry Adkins, whistling as he is slowly engulfed in clouds. His seeming ability to fade—to appear ethereal, even to disappear—evokes the ways that race and gender inform a person’s capacity, or lack thereof, to determine their desired level of public visibility. ‘Cloudscape’ makes Adkins an apparition, more spirit than body, while distorting the viewer’s temporal and spatial understanding of the world within the video.

‘‘The artworks accompanying ‘Cloudscape’ allude to atmospheric conditions while also reflecting individualized articulations of weight. They challenge, and even circumvent, the embodied ways that we relate to our surroundings.’’

Ed Cervone: How a Maine college has adjusted to pandemic and recession

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

In October 2019, NEBHE called together a group of economists and higher education leaders for a meeting at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston to discuss the future of higher education (Preparing for Another Recession?). No one suspected that just months later, a global pandemic would turn the world upside down. Today, the same challenges highlighted at the meeting persist. The pandemic has only amplified the situation and accelerated the timeline. It also has forced the hands of institutions to advance some of the changes that will sustain higher education institutions through this crisis and beyond.

At the October 2019 meeting, the panelists identified the primary challenges facing colleges and universities: a declining pool of traditional-aged students, mounting student debt, increasing student-loan-default rates and growing income inequality.

Taken together, these trends were creating a perfect storm, simultaneously putting a college education out of reach for more and more students and forcing some New England higher-education institutions to close or merge with other institutions. Those trends were expected to continue.

Just three months later, COVID-19 had begun spreading across the U.S., and the education system had to shut down in-person learning. Students returned home to finish the semester. Higher-education institutions were forced to go fully remote in a matter of weeks. Institutions struggled to deliver content and keep students engaged. Inequities across the system were accentuated, as many students faced connectivity obstacles. Households felt the economic crunch as the unemployment rate increased sharply.

By summer, the pandemic was in full swing. Higher-education institutions looked to the fall. They had to convince students and their families that it would be safe to return to campus in an uncertain and potentially dangerous environment. Safety measures introduced new budgetary challenges: physical infrastructure upgrades, PPE and the development of screening and testing regimens.

In the fall, students resumed their education through combinations of remote and in-person instruction. Activities and engagement looked very different due to health and safety protocols. Many institutions experienced a larger than usual summer melt due to concerns from students and families about COVID and the college experience.

Despite these added challenges, New England higher-education institutions have adapted to keep students engaged in their education, but are running on small margins and expending unbudgeted funds to continue operations during the public-health crisis. Recruiting the next class of students is proving to be a challenge. The shrinking pool of recruits will contract even more and reaching them is much more difficult. Many low- and moderate-income families will find accessing higher education even harder and may choose to defer postsecondary learning.

Change is difficult but a crisis can provide necessary motivation. Maine institutions are using this opportunity to make the changes needed to address the current crisis that will also set them on a more sustainable path over the long term. Maine has a competitive advantage relative to the nation. A low-density rural setting and the comprehensive public-health response from Gov. Janet Mills have kept the overall incidence rate down. Public and private higher-education institutions coordinated their response, developed a set of protocols for resuming in-person education that were reviewed by the governor and public health officials, and successfully returned to in-person education in the fall.

In addition, Mills established the Economic Recovery Committee in May and charged the panel with identifying actions and investments that would be necessary to get the Maine economy back on track. This public process has reinforced the critical ties between education and a healthy economy. Not only is higher education a focus of the work, but the governor appointed Thomas College President Laurie Lachance to co-chair the effort. In addition, the governor appointed University of New England (in Biddeford, Maine) President James Herbert, University of Maine at Augusta President Rebecca Wyke, and Southern Maine Community College President Joseph Cassidy to serve on the committee.

At the individual institution level, a wide array of innovations will enable Thomas College to endure the pandemic and position itself for the future. Consider:

Affordability. Most Thomas College students come from low- to medium-income households and are the first in their families to attend college, so-called “first-generation” students. Cost will always be top of mind. For motivated students, Thomas has an accelerated pathway that allows students to earn their bachelor’s degree in three years (sometimes two) and they have the option of doing a plus-one to earn their master’s. This, coupled with generous merit scholarship packages (up to $72,000 of scholarship over four years) and a significant transition to Open Educational Resources to reduce book costs, represents real savings and the opportunity to be earning sooner than their peers.

Student success supports. Accelerated programs (or any program, for that matter) are not viable without purposeful strategies to keep students on track to complete based on their plans. In addition to a traditional array of academic and financial supports, Thomas College has invested in a true wraparound offering serving the whole student. For eligible students, Thomas has a dedicated TRIO Student Support Services program. Funded through a U.S. Department of Education grant, the program provides academic and personal support to students who are first-generation, are from families of modest incomes, or who have an identified disability. The benefits include individualized academic coaching, financial literacy development and college planning support for families. Thomas was also first in the nation to have a College Success program through JMG (Maine’s Jobs for America’s Graduates affiliate). Thomas College has expanded physical- and mental- health services in the wake of the pandemic, including our innovative Get Out And Live program, which uses Maine’s vast natural setting to provide a range of exciting four-season, outdoor activities for the whole campus community.

Employability. Thomas College students see preparing for a rewarding career as part of their college experience. This is core to the college’s mission and more important than ever in an uncertain economic environment. It is so important that it is guaranteed through the college’s Guaranteed Job Program. Thomas College’s Centers of Innovation focus on the employability of each student. Students pursue a core academic experience in their chosen field, and staff work with each student starting in their first semester to increase their professional and career development. This means field experiences and internships with Maine’s top employers. About 75 percent of Thomas College students have an internship before graduation. As part of their college experience, Thomas College students are coached to earn professional certificates, licenses and digital badges prior to graduation that make them stand out in their professional fields and improve their earning potential. These might include certificates in specific sectors like accounting and real estate or digital badges that show proficiency in professional skills like Design Thinking or Project Management, to name just a few. On the academic side, Thomas has expanded both undergraduate and graduate degree offerings to programs where the market has great demand, including Cybersecurity, Business Analytics, Applied Math, Project Management and Digital Media. Delivery is flexible in terms of mode and timing. And the institution is now offering Certificates of Advance Study (15-credit programs) in Cybersecurity, Human Resource Management and Project Management to meet the stated needs of our business partners seeking to upskill their employees.

Looking Ahead

Some of these changes and investments align with challenges identified before the pandemic as necessary if higher education institutions are to survive and sustain changing demographic and economic trends. The pandemic provided the opportunity to focus on these more quickly, allowing institutions such as Thomas College to right the ship today and set the right course for tomorrow.

Ed Cervone is vice president of innovative partnerships and the executive director of the Center for Innovation in Education at Thomas College, in Waterville, Maine., also the home of Colby College.

The art of saving seeds

Installation view of the show SEED-O-MATIC at the Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, through May 8.

The museum (remarkably large for a small , if well-endowed, college), explains that the artists Emma Dorothy Conley and Halley Roberts created the show in conjunction with the Center for Genomic Gastronomy (CGG), which is dedicated to researching, prototyping and inspiring a "more just, biodiverse, and beautiful food system". As large agrochemical companies buy out seed suppliers and patent their genetic information agricultural biodiversity and food sovereignty are threatened.

Colby College Museum of Art

Photo by Colby Mariam

Waterville used to be a bustling factory town; now it’s best known for Colby. A Wikipedia entry notes:

“The Kennebec River and Messalonskee Stream provided water power for mills, including several sawmills, a gristmill, a sash and blind factory, a furniture factory, and a shovel handle factory. There was also a carriage and sleigh factory, boot shop, brickyard, and tannery. On Sept. 27, 1849, the Androscoggin and Kennebec Railroad opened to Waterville. It would become part of the Maine Central Railroad, which in 1870 established locomotive and car repair shops in the thriving mill town….

‘‘The Ticonic Water Power & Manufacturing Company was formed in 1866 and soon built a dam across the Kennebec. After a change of ownership in 1873, the company began construction on what would become the Lockwood Manufacturing Company, a cotton textile plant. A second mill was added, and by 1900 the firm dominated the riverfront and employed 1,300 workers. …. The iron Waterville-Winslow Footbridge opened in 1901, as a means for Waterville residents to commute to Winslow for work in the Hollingsworth & Whitney Co. and Wyandotte Worsted Co. mills, but in less than a year was carried away by the highest river level since 1832. Rebuilt in 1903, it would be called the Two Cent Bridge because of its toll. In 1902, the Beaux-Arts style City Hall and Opera House designed by George Gilman Adams was dedicated. In 2002, the C.F. Hathaway Company, one of the last remaining factories in the United States producing high-end dress shirts, was purchased by Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway company and was closed after over 160 years of operation in the city….

“In 1813, the Maine Literary and Theological Institution was established. It would be renamed Waterville College in 1821, then Colby College in 1867. Thomas College was established in 1894. The Latin School was founded in 1820 to prepare students to attend Colby and other colleges, and was subsequently named Waterville Academy, Waterville Classical Institute, and Coburn Classical Institute.’’

One Post Office Square, a multiple-use facility, in downtown Waterville