In Greater Boston, the intersection of the pandemic and immigration

Cambridge Hospital, part of the Cambridge Health Alliance

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

CAMBRIDGE, Mass.

A year into the global pandemic, we are grappling with the scale of its impact and the conditions that created, permitted and exacerbated it. For those of us in the mental health field, tentative strides toward telepsychiatry pivoted to a sudden semi-permanent virtual health-care delivery system. Questions of efficacy, equity and risk management have been raised, particularly for underserved and immigrant populations. The structures of our work and its pillars (physical proximity, co-regulation, confidentiality, in-person crisis assessment) have shifted, leading to other unexpected proximities and perhaps intimacies—seeing into patients’ homes, seeing how they interact with their children, speaking with patients with their abusive partners in the room, listening to the conversation, and patients seeing into our lives.

As the pandemic crisis morphs, it is unclear if we are at the point to do meaningful reflective work, but for now, I offer some thoughts through the lens of my work at Cambridge Health Alliance (CHA), an academic health-care system serving about 140,000 patients in the Boston Metro North region.

CHA is a unique system: a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School, which operates the Cambridge Public Health Department and articulates as “core to the mission,” health equity and social justice to underserved, medically indigent populations with a special focus on underserved people in our communities. Within the hospital’s Department of Psychiatry, four linguistic minority mental-health teams serve Haitian, Latinx, Portuguese-speaking (including Portugal, Cape Verde and Brazil) and Asian patients.

While we endeavour to gather data on this across CHA, anecdotal evidence from the minority linguistic teams supports the existing research suggesting that immigrant and communities of color are bearing a disappropriate impact of COVID-19 in multiple intersecting and devastating ways: higher burden of disease and mortality rates, poorer care and access to care, overrepresentation in poorly reimbursed and “front-facing” vulnerable jobs such as cleaning services in hospitals and assisted care facilities, personal care attendants and home health aides, and overrepresentation in industries that have been hardest hit by the pandemic such as food service, thereby facing catastrophic loss of income.

These patients also face crowded multigenerational living conditions and unregulated and crowded work conditions. These “collapsing effects” are further exacerbated by reports from our patients that they are also being targeted by hateful rhetoric such as “the China virus” and larger anti-immigrant sentiment stoked by the Trump administration and the accompanying narrative of “economic anxiety” that has masked the racialized targeting of immigrants at their workplaces and beyond.

Telehealth. As we provide services, we have also observed that, despite privacy concerns, access to and use of our care has expanded due to the flexibility of telehealth. Patients tell us that they no longer have to take the day off from work to come to a therapy appointment and have found care more accessible and understanding of the demands of their material lives.

Some immigrant patients report that since they use phone and video applications to stay in touch with family members, using these tools for psychiatric care feels normative and familiar. For deeply traumatized individuals, despite the loss of face-to-face contact, the fact that they do not have to encounter the stresses inherent in being in contact with others out in the world has made it more possible for them to consistently engage in care with reduced fear as relates to their anxiety and/or PTSD. These are interesting observations as we try to tailor care and understand “what works for whom.”

Immigrant service providers. Another theme in the dynamics of care during the pandemic is found in the experiences of immigrant service providers whose work has been stretched in previously unrecognizable ways—and remains often invisible.

Prior to the pandemic, for example, CHA had established the Volunteer Health Advisors program, which trains respected community health workers, often individuals who were healthcare providers in their home country, who have a close understanding of the community they serve. They participate in community events such as health fairs to facilitate health education and access to services and can serve as a trusted link to health and social services and underserved communities.

What we have seen during the pandemic is even greater strain on immigrant and refugee services providers who are often the front line of contact. We have provided various “care for the caregiver” workshops that address secondary or vicarious trauma to such groups such as medical interpreters often in the position of giving grave or devastating news to families about COVID-19-related deaths as well as school liaisons and school personnel, working with children who may have lost multiple family members to the virus, often the primary breadwinners, leaving them in economic peril.

While such supportive efforts are not negligible, a public system like ours is vulnerable to operating within crisis-driven discourse and decision making. With the pandemic exacerbating inequities, organizational scholars have noted in various contexts that a state of crisis can become institutionalized. This can foreclose efforts at equity that includes both patient care as well as care for those providing it. The challenge going forward will involve keeping these issues at the forefront of decisions regarding catalyzing technology and the resulting demands on our workforce.

Diya Kallivayalil , Ph.D., is the director of training at the Victims of Violence Program at the Cambridge Health Alliance and a faculty member in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

Martha Bebinger: Have you asked your doctor about global warming?

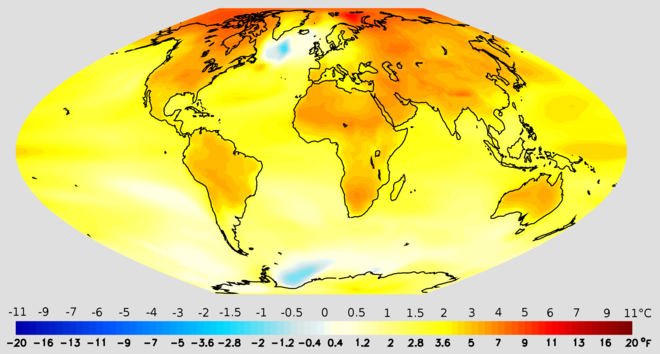

Projected change in annual mean surface air temperature from the late 20th century to the middle 21st century, based on a medium emissions scenario. This scenario assumes that no future policies are adopted to limit greenhouse gas emissions.

— Image credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

BOSTON

When Michael Howard arrived for a checkup with his lung specialist, he was worried about how his body would cope with the heat and humidity of a Boston summer.

“I lived in Florida for 14 years, and I moved back because the humidity was just too much,” Howard told pulmonologist Dr. Mary Rice as he settled into an exam room chair at a Beth Israel Deaconess HealthCare clinic.

Howard, 57, has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a progressive lung disease that can be exacerbated by heat and humidity. Even inside a comfortable, climate-controlled room, his oxygen levels worried Rice.

Howard reluctantly agreed to try using portable oxygen, resigned to wearing the clear plastic tubes looped over his ears and inserted into his nostrils. He assured Rice he has an air conditioner and will stay inside on extremely hot days. The doctor and patient agreed that Howard should take his walks in the evenings to be sure he gets enough exercise without overheating.

Then Howard turned to Rice with a question she didn’t encounter in medical school: “Can I ask you: Last summer, why was it so hot?”

Rice, who studies air pollution, was ready.

“The overall trend of the hotter summers that we’re seeing [is] due to climate change,” Rice said.

For Rice, connecting climate-change consequences — heat waves, more pollen, longer allergy seasons — to her patients’ health is becoming routine. She is among a small but growing number of doctors and nurses who discuss those connections with patients.

In June, the American Medical Association, American Academy of Pediatrics and American Heart Association were among a long list of medical and public health groups that issued a call to action asking the U.S. government, business and leaders to recognize climate change as a health emergency.

The World Health Organization calls climate change “the greatest health challenge of the 21st century,” and a dozen U.S. medical societies urge action to limit global warming.

Some medical societies provide patients with information that explains the related health risks. But none have guidelines on how providers should talk to patients about climate change.

There is no concrete list of “do’s” — as in wear a seat belt, use sunscreen and get exercise — or “don’ts” — as in don’t smoke, don’t drink too much and don’t text while driving ― that doctors can talk about with patients.

Climate change is different, said Rice, because an individual patient can’t prevent it. So Rice focuses on steps her patients can take to cope with the consequences of heat waves, such as more potent pollen and a longer allergy season.

That was Mary Heafy’s main complaint. The 64-year-old has asthma that is worse during the allergy season. During her appointment with Rice, Heafy wanted to know why her eyes and nose were running and her chest feels tight for longer periods every year.

“It feels like once [the allergy season] starts in the springtime, it doesn’t end until there’s a killing frost,” Heafy told Rice.

“Yes,” Rice nodded, “because of global warming, the plants are flowering earlier in the spring. After hot summers, the trees are releasing more pollen the following season.”

Rice checks Mary Heafy's breathing during a checkup for her asthma at the Beth Israel Deaconess clinic. Climate change does seem to be extending the Boston region's ragweed season, Rice tells Heafy.

Rice, who studies the health effects of air pollution, talks with Howard about his increased breathing problems and their possible link to the heat waves, increased pollen and longer allergy seasons associated with climate change.

So Heafy may need stronger medicines and more air filters, her doctor said, and may spend more days wearing a mask — although the effort of breathing through a mask is hard on her lungs as well.

As she and the doctor finalized a prescription plan, Heafy observed that “physicians talk about things like smoking, but I don’t know that every physician talks about the environmental impact.”

Why do so few doctors talk about the impact of the environment on health? Besides a lack of guidelines, doctors say, they don’t have time during a 15- to 20-minute visit to broach something as complicated as climate change.

And the topic can be controversial: While a recent Pew Research Center poll found that 59% of Americans think climate change affects their local community “a great deal or some,” only 31% say it affects them personally, and views vary widely by political party.

We contacted energy-industry trade groups to ask what role — if any — medical providers should have in the climate change conversation, but neither the American Petroleum Institute nor the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers returned calls or email requests for comment.

Some doctors say they worry about challenging a patient’s beliefs on the sometimes fraught topic, according to Dr. Nitin Damle, a past president of the American College of Physicians.

“It’s a difficult conversation to have,” said Damle, who practices internal medicine in Wakefield, R.I.

Damle said he “takes the temperature” of patients, with some general questions about the environment or the weather, before deciding if he’ll suggest that climate change is affecting their health.

Dr. Gaurab Basu, a primary-care physician at Cambridge Health Alliance, said he’s ready if patients want to talk about climate change, but he doesn’t bring it up. He first must make sure patients feel safe in the exam room, he said, and raising a controversial political issue might erode that feeling.

“I have to be honest about the science and the threat that is there, and it is quite alarming,” Basu said.

So alarming, Basu said, that he often refers patients to counseling. Psychiatrists concerned about the effects of climate change on mental healthsay there are no standards of care in their profession yet, but some common responses are emerging.

One environmental group isn’t waiting for doctors and nurses to figure out how to talk to patients about climate change.

Molly Rauch, the public health policy director with Moms Clean Air Force, a project of the Environmental Defense Fund, urges the group’s more than 1 million members to ask doctors and nurses for guidance. For example: When should parents keep children indoors because the outdoor air is too dirty?

“This isn’t too scary for us to hear about,” Rauch said. “We are hungry for information about this. We want to know.”

This story is part of a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

Martha Bebinger, WBUR: marthab@wbur.org, @mbebinger