‘Much harder work’

Mindy Kaling

“Write your own part. It is the only way I've gotten anywhere. It is much harder work, but sometimes you have to take destiny into your own hands. It forces you to think about what your strengths really are, and once you find them, you can showcase them, and no one can stop you.”

— Mindy Kaling (born 1979), American actress, comedian, screenwriter and producer. She grew up in Cambridge, Mass., and graduated from Dartmouth College.

Let the river do the heating

Spring on the Charles River Esplanade

— Photo by Ingfbruno

#heat pump #Charles River

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

Cleaner-energy progress continues in unexpected ways. I recently learned this:

Vicinity Energy, based in Boston, is partnering with Germany’s MAN Energy Solutions to collaborate in developing heat-pump systems for steam generation using water from the Charles River. Vicinity says it will install such an industrial-scale complex at its Kendall Station facility (in Cambridge) by 2026.

A heat pump extracts heat from a source, such as the air, geothermal energy in the ground or nearby sources of water or waste heat from a factory. It then amplifies and transfers the heat to where it is needed.

The giant heat-pump complex will generate steam with which to heat many large buildings in Cambridge and Boston, which could save owners and renters a lot of money.

Vicinity says that this will be the largest such facility in the U.S. and “will be powered by renewable electricity to safely and efficiently harvest energy from the Charles River, returning it at a lower temperature.’’ The idea is to renewably harvest thermal energy from rivers and oceans, which are warming because of climate change, thus helping decarbonize localities, especially cities.

How about something like this in Rhode Island? Lots of water available.

Hit these links:

Water-source heat-exchanger being installed in England

Run by ‘Patton in pumps’

The latter version, since closed, of Upstairs at the Pudding

“But worse, it was a new apartment. We both knew that, in New England, old was better. Old was cozy; old, like our farmhouse, like the Pudding, had magic and charm.”

― Charlotte Silver in her memoir Charlotte Au Chocolat: Memories of a Restaurant Girlhood

Amazon describes the book:

“Like Eloise growing up in the Plaza Hotel, Charlotte Silver grew up in her mother's restaurant. Located in Harvard Square, Upstairs at the Pudding {in reference to the original version or the restaurant being in the former Hasty Pudding Theatricals building before being moved nearby} was a confection of pink linen tablecloths and twinkling chandeliers, a decadent backdrop for childhood. Over dinners of foie gras and Dover sole, always served with a Shirley Temple, Charlotte kept company with a rotating cast of eccentric staff members. After dinner, in her frilly party dress, she often caught a nap under the bar until closing time. Her one constant was her glamorous, indomitable mother, nicknamed ‘Patton in Pumps,’ a wasp-waisted woman in cocktail dress and stilettos who shouldered the burden of raising a family and running a kitchen. Charlotte's unconventional upbringing takes its toll, and as she grows up she wishes her increasingly busy mother were more of a presence in her life. But when the restaurant-forever teetering on the brink of financial collapse-looks as if it may finally be closing, Charlotte comes to realize the sacrifices her mother has made to keep the family and restaurant afloat and gains a new appreciation of the world her mother has built.’’

Former location of the Hasty Pudding Club at 12 Holyoke Street, Cambridge, now owned by Harvard University but still used by Hasty Pudding Theatricals.

‘Large and small visions of nature’

“Multi-cellular” (watercolor, colored pencil, ink and encaustic medium on Strathmore mixed media paper), by Cambridge, Mass.-based artist Katrina Abbott.

She says:

“Nature, color and climate change inspire my art. By representing the beauty and diversity of the natural world, I hope to inspire viewers to take a closer look at the world around us, and ultimately be more thoughtful and careful stewards of our planet. I bring my background in marine biology and environmental studies and the experience of years spent both on the ocean and in the backcountry to my art. I paint, print and work in wax to represent large and small visions of nature from the earth from space to frogs, cells and diatoms.’’

Cambridge City Hall.

Another triumph for New England biotech?

The Philip A. Sharp Building, in Cambridge, which houses the headquarters of Biogen

— Photo by Astrophobe

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’ in GoLocal24.com

This is another “we’ll see’’ situation that gives hope.

Japan’s Eisai Co. and Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen Inc. have developed a drug, called lecanemab, that destroys the amyloid protein plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Patients in the drug trial have had a slowing of symptoms. Researchers have much to learn about the drug’s benefits, side-effects and cost, but the apparent breakthrough may the most hopeful sign yet that a highly effective treatment of this terrible dementia might be in the offing.

Hit this link for The New England Journal of Medicine article on this.

Further, since the buildup of abnormal proteins in the brain is also seen in such (usually) old-age-related ailments as Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease, lecanemab may have wider applications than just for Alzheimer’s as the population continues to age.

This could be another triumph for New England’s bio-tech industry, but it may take many months to find out for sure.

‘Insecurity and surprise’

“Resonance” (encaustic painting), by Deborah Peeples, who has a studio in Somerville, Mass., and lives in neighboring Cambridge.

She writes in the New England Wax Web site:

“Painting is my sensual response to the world, a time-release recording of the sounds, smells, and intensity of a moment. Abstraction is a language that traces my inner turbulence and exuberance. The natural translucent materials of beeswax and damar contain a lush baroque beauty. Mixing pigments, playing with opacity, heating the panel, always touching, breathing the smell of the hot beeswax, brings a slowness and intimacy to the process. The work is layered, incised, inlaid, and scraped; lines cut into the surface, either sharp or blurred, feel alternately vulnerable and impenetrable. Humor and playfulness are found in the saturated, syncopated color and jostling shapes that play off an underlying grid. These juxtapositions create imbalance, insecurity, and surprise, a metaphor for the search to find my place in the world’’.

Harvard Square, in Cambridge

— Photo by chensiyuan

And ‘about meat prices’

The Porter Square Shopping Center in 2009.

“You can’t assume anything in politics. That’s why every Saturday I walk around my district. I talk to the longshoremen in Charlestown. I listen to the people in East Boston and their concern on the airport noise. I walk down to the Star Market in Porter Square, and people tell me about meat prices.’’

— Thomas P. {“Tip”) O’Neill (1912-1994), Massachusetts congressman who served as U.S. House speaker in 1977-87.

The Rand Estate, on site of what is now Porter Square Shopping Center, 1900 or earlier.

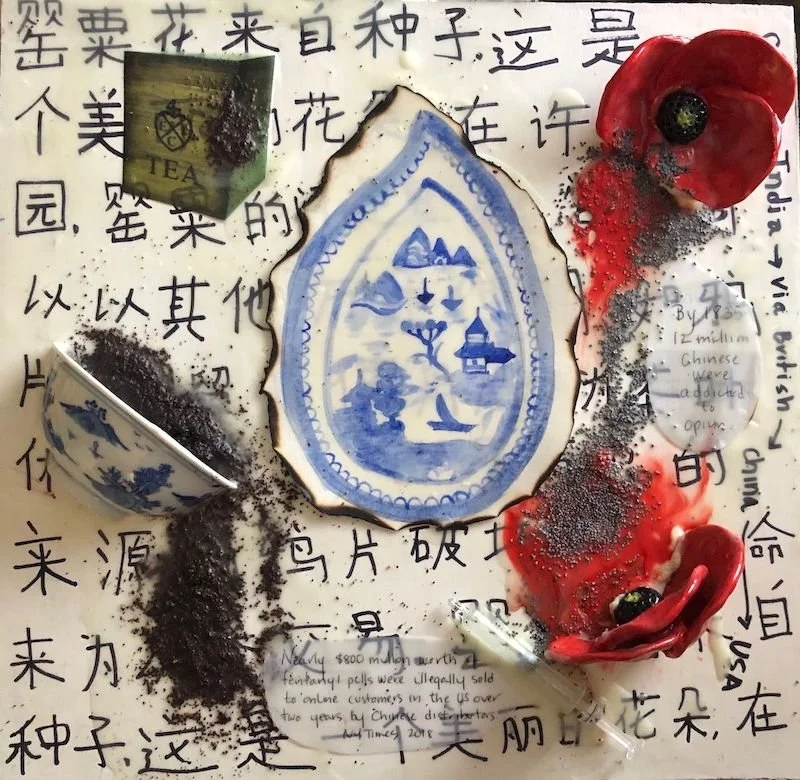

Beauty from New England’s drugged-up China Trade

“China Trade: Opium through the Ages” (encaustic, ceramic made and found objects, tea leaves, poppy seeds on panel), by Cambridge,Mass.-based artist Katrina Abbott.

New England’s “China Trade,’’ in the late 18th Century and the first half of the 19th, created great wealth for some in the region, mostly in and around its ports. Some of the trade involved selling opium to the Chinese. Much of that wealth was invested in what became very lucrative industries, such as textile, shoe and machinery manufacturing and railroads.

In her Web site, Ms. Abbott describes herself thusly:

“Katrina Abbott came to art later in life after her twins were born. Previous to this, she spent 25 years in education, including outdoor education, ocean education at sea and urban public school reform. With a BA in Environmental Biology and a Masters in Botany (studying seaweed!), she reflects her interest in and concern for the natural world in her art. She represents the nature in print, paint, wax ( encaustic) and mosaic. She is a member of the Cambridge Art Association and New England Wax and lives in Cambridge with her husband, their 20 year old boy/girl twins and small brown rabbit named Jarvis.’’

Derby House, in Salem, Mass. Elias Hasket Derby was among the wealthiest and most celebrated of post-Revolutionary War merchants in Salem. He was owner of the Grand Turk, said to be the first New England vessel to be used to trade directly with China. There were many mansions built by merchants in the China Trade, some of which was a drug trade.

—Photo by Daderot

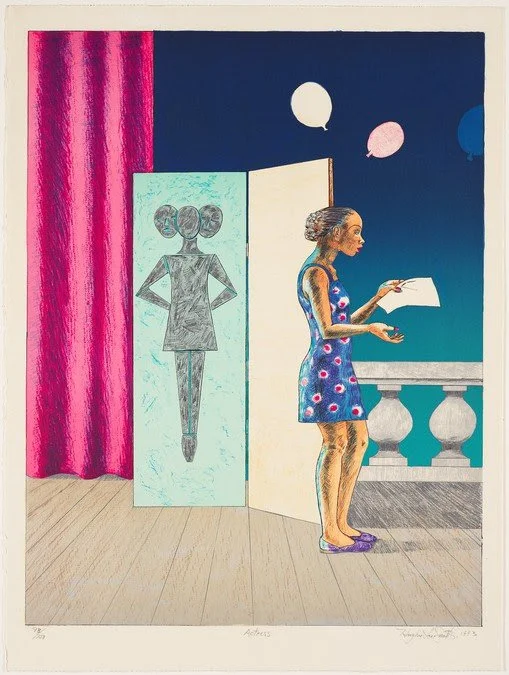

Stage fright

“Actress” (1993) (offset color lithograph), by Hughie Lee-Smith (1915-1999), in the show “Prints from the Brandywine Workshop and Archives: Creative Communities,’’ at Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Mass., opening March 4.

Dare to fail

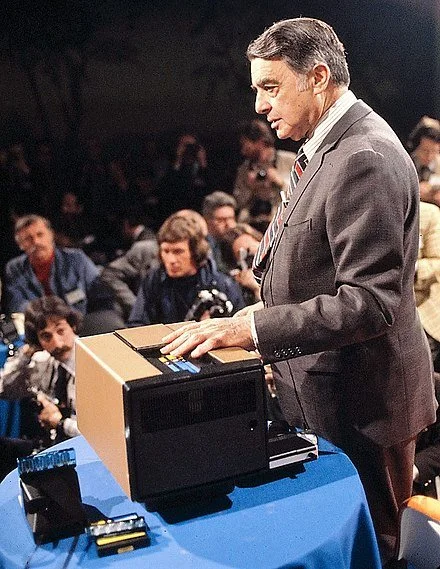

“Dr.” Edwin Land presenting the Polavision home movie system, in1977.

“An essential aspect of creativity is not being afraid to fail.’’

— Edwin Herbert Land (1909-1991) scientist and founder of Polaroid Corporation, founded and based for many years in Cambridge, Mass. (It’s now based in Minnesota.)

He was best known as the co-founder of the Polaroid Corp. for inventing inexpensive filters for polarizing light, in-camera instant photography, and the retinex theory of color vision, among other things. His Polaroid instant camera went on sale in late 1948 and made it possible for a picture to be taken and developed in 60 seconds or less.

For decades, he was probably the best known figure in Greater Boston’s world renown high-technology sector. He was always called “Dr. Land,’’ although he never got a college undergraduate or advanced degree. Later in his career, though, Harvard gave him an honorary doctorate for his scientific and business achievements.

Polaroid Land (name for Mr., Land) Camera Model 95, the first commercially available instant camera, in 1948.

Bring back this urban starter housing

A three-decker in Cambridge, Mass.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s a very useful article by Aaron Renn in Governing Magazine about how “poor neighborhoods” with lots of owner-occupied dwellings provided a springboard for people to enter the middle class. It sure beats massive, impersonal and often crime-ridden public-housing projects. An example would be those New England neighborhoods of “three-deckers” in places like South Boston. The owners often live on just one floor and rent out the rest of the building – a way to start gaining middle-class wealth.

But, as I’ve noticed in the U.S. cities where I’ve lived – Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Providence – public policies and changing social attitudes have eroded the benefits of this “starter housing’’ for years. Among Mr. Renn’s observations:

“The rise of zoning and ever-stricter building codes … played a role, especially in recent years, preventing the construction of traditional starter neighborhoods.”

“Changing zoning regulations to create more affordable neighborhoods in some of America’s most expensive cities would help establish platforms for upward mobility. …{But} other factors played into making these old neighborhoods what they were. They were high in social capital, characterized by intact married families, and populated with people who possessed the skills needed for building maintenance. These exist today in some immigrant communities, but less so in society at large.’’

(Ah yes, the collapse of marriage and the stability that went with it.)

Policy makers take note, particularly considering a housing-cost crisis that shows few signs of abating.

To read Mr. Renn’s article, please hit this link.

Judith Graham: With the arrival of Aduhelm, what is 'mild cognitive impairment'?

19th Century drawing of man with dementia

The approval of a controversial new drug for Alzheimer’s disease, Aduhelm, made by Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen, is shining a spotlight on mild cognitive impairment — problems with memory, attention, language or other cognitive tasks that exceed changes expected with normal aging.

(Kendall Square in Cambridge, Biogen’s neighborhood, has become arguably the bio-tech center of the world.)

After initially indicating that it could be prescribed to anyone with dementia, the Food and Drug Administration now specifies that the prescription drug be given only to individuals with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage Alzheimer’s, the groups in which the medication was studied.

Yet this narrower recommendation raises questions. What does a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment mean? Is Aduhelm appropriate for all people with mild cognitive impairment, or only some? And who should decide which patients qualify for treatment: dementia specialists or primary-care physicians?

Controversy surrounds Aduhelm because its effectiveness hasn’t been proved, its cost is high (an estimated $56,000 a year, not including expenses for imaging and monthly infusions), and its potential side-effects are significant (41 percent of patients in the drug’s clinical trials experienced brain swelling and bleeding).

Furthermore, an FDA advisory committee strongly recommended against Aduhelm’s approval, and Congress is investigating the process leading to the FDA’s decision. Medicare is studying whether it should cover the medication, and the Department of Veterans Affairs has declined to do so under most circumstances.

Clinical trials for Aduhelm excluded people over age 85; those taking blood thinners; those who had experienced a stroke; and those with cardiovascular disease or impaired kidney or liver function, among other conditions. If those criteria were broadly applied, 85 percent of people with mild cognitive impairment would not qualify to take the medication, according to a new research letter in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Given these considerations, carefully selecting patients with mild cognitive impairment who might respond to Aduhelm is “becoming a priority,” said Dr. Kenneth Langa, a professor of medicine, health management and policy at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Ronald Petersen, who directs the Mayo Clinic’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, said, “One of the biggest issues we’re dealing with since Aduhelm’s approval is, ‘Are appropriate patients going to be given this drug?’”

Here’s what people should know about mild cognitive impairment based on a review of research studies and conversations with leading experts:

Basics. Mild cognitive impairment is often referred to as a borderline state between normal cognition and dementia. But this can be misleading. Although a significant number of people with mild cognitive impairment eventually develop dementia — usually Alzheimer’s disease — many do not.

Cognitive symptoms — for instance, difficulties with short-term memory or planning — are often subtle but they persist and represent a decline from previous functioning. Yet a person with the condition may still be working or driving and appear entirely normal. By definition, mild cognitive impairment leaves intact a person’s ability to perform daily activities independently.

According to an American Academy of Neurology review of dozens of stuies, published in 2018, mild cognitive impairment affects nearly 7 percent of people ages 60 to 64, 10 percent of those 70 to 74 and 25 percent of 80-to-84-year-olds.

Causes. Mild cognitive impairment can be caused by biological processes (the accumulation of amyloid beta and tau proteins and changes in the brain’s structure) linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Between 40 percent and 60 percent of people with mild cognitive impairment have evidence of Alzheimer’s-related brain pathology, according to a 2019 review.

But cognitive symptoms can also be caused by other factors, including small strokes; poorly managed conditions, such as diabetes, depression and sleep apnea; responses to medications; thyroid disease; and unrecognized hearing loss. When these issues are treated, normal cognition may be restored or further decline forestalled.

Subtypes. During the past decade, experts have identified four subtypes of mild cognitive impairment. Each subtype appears to carry a different risk of progressing to Alzheimer’s disease, but precise estimates haven’t been established.

People with memory problems and multiple medical issues who are found to have changes in their brain through imaging tests are thought to be at greatest risk. “If biomarker tests converge and show abnormalities in amyloid, tau and neuro-degeneration, you can be pretty certain a person with MCI has the beginnings of Alzheimer’s in their brain and that disease will continue to evolve,” said Dr. Howard Chertkow, chairperson for cognitive neurology and innovation at Baycrest, an academic health-sciences center in Toronto that specializes in care for older adults.

Diagnosis. Usually, this process begins when older adults tell their doctors that “something isn’t right with my memory or my thinking” — a so-called subjective cognitive complaint. Short cognitive tests can confirm whether objective evidence of impairment exists. Other tests can determine whether a person is still able to perform daily activities successfully.

More sophisticated neuropsychological tests can be helpful if there is uncertainty about findings or a need to better assess the extent of impairment. But “there is a shortage of physicians with expertise in dementia — neurologists, geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists” — who can undertake comprehensive evaluations, said Kathryn Phillips, director of health services research and health economics at the University of California-San Francisco School of Pharmacy.

The most important step is taking a careful medical history that documents whether a decline in functioning from an individual’s baseline has occurred and investigating possible causes such as sleep patterns, mental health concerns and inadequate management of chronic conditions that need attention.

Mild cognitive impairment “isn’t necessarily straightforward to recognize, because people’s thinking and memory changes over time [with advancing age] and the question becomes ‘Is this something more than that?’” said Dr. Zoe Arvanitakis, a neurologist and director of Rush University’s Rush Memory Clinic, in Chicago.

More than one set of tests is needed to rule out the possibility that someone performed poorly because they were nervous or sleep-deprived or had a bad day. “Administering tests to people over time can do a pretty good job of identifying who’s actually declining and who’s not,” Langa said.

Progression. Mild cognitive impairment doesn’t always progress to dementia, nor does it usually do so quickly. But this isn’t well understood. And estimates of progression vary, based on whether patients are seen in specialty dementia clinics or in community medical clinics and how long patients are followed.

A review of 41 studies found that 5 percent of patients treated in community settings each year went on to develop dementia. For those seen in dementia clinics — typically, patients with more serious symptoms — the rate was 10 percent. The American Academy of Neurology’s review found that after two years 15 percent of patients were observed to have dementia.

Progression to dementia isn’t the only path that people follow. A sizable portion of patients with mild cognitive impairment — from 14 percent to 38 percent — are discovered to have normal cognition upon further testing. Another portion remains stable over time. (In both cases, this may be because underlying risk factors — poor sleep, for instance, or poorly controlled diabetes or thyroid disease — have been addressed.) Still another group of patients fluctuate, sometimes improving and sometimes declining, with periods of stability in between.

“You really need to follow people over time — for up to 10 years — to have an idea of what is going on with them,” said Dr. Oscar Lopez, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh.

Specialists versus generalists. Only people with mild cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer’s should be considered for treatment with Aduhelm, experts agreed. “The question you want to ask your doctor is, ‘Do I have MCI [mild cognitive impairment] due to Alzheimer’s disease?’” Chertkow said.

Because this medication targets amyloid, a sticky protein that is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s, confirmation of amyloid accumulation through a PET scan or spinal tap should be a prerequisite. But the presence of amyloid isn’t determinative: One-third of older adults with normal cognition have been found to have amyloid deposits in their brains.

Because of these complexities, “I think, for the early rollout of a complex drug like this, treatment should be overseen by specialists, at least initially,” said Petersen of the Mayo Clinic. Arvanitakis of Rush University agreed. “If someone is really and truly interested in trying this medication, at this point I would recommend it be done under the care of a psychiatrist or neurologist or someone who really specializes in cognition,” she said.

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Judith Graham: khn.navigatingaging@gmail.com, @judith_graham

Elisabeth Rosenthal: Why we may never know if Biogen’s Alzheimer’s drug works

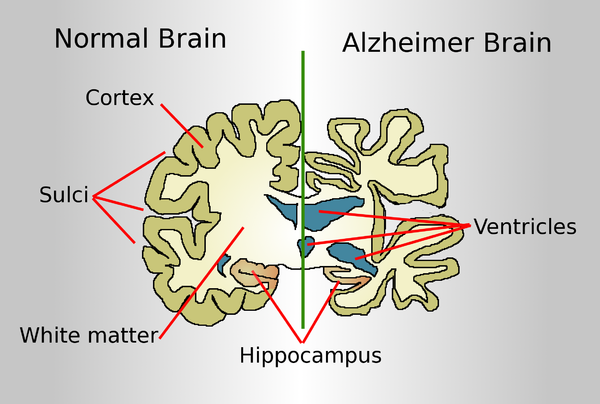

A normal brain on the left and a late-stage Alzheimer's brain on the right.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval in June of a drug purporting to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease was widely celebrated, but it also touched off alarms. There were worries in the scientific community about the drug, developed by Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen, mixed results in studies — the FDA’s own expert advisory panel was nearly unanimous in opposing its approval. And the annual $56,000 price tag of the infusion drug, Aduhelm, was decried for potentially adding costs in the tens of billions of dollars to Medicare and Medicaid.

But lost in this discussion is the underlying problem with using the FDA’s “accelerated” pathway to approve drugs for conditions such as Alzheimer’s, a slow, degenerative disease. Though patients will start taking it, if the past is any guide, the world may have to wait many years to find out whether Aduhelm is actually effective — and may never know for sure.

The accelerated approval process, begun in 1992, is an outgrowth of the HIV/AIDS crisis. The process was designed to approve for sale — temporarily — drugs that studies had shown might be promising but that had not yet met the agency’s gold standard of “safe and effective,” in situations where the drug offered potential benefit and where there was no other option.

Unfortunately, the process has too often amounted to a commercial end run around the agency.

The FDA explained its controversial decision to greenlight the Biogen pharmaceutical company’s latest product: Families are desperate, and there is no other Alzheimer’s treatment. Also, importantly, when drugs receive this type of fast-track approval, manufacturers are required to do further controlled studies “to verify the drug’s clinical benefit.” If those studies fail “to verify clinical benefit, the FDA may” — may — withdraw them.

But those subsequent studies have often taken years to complete, if they are finished at all. That’s in part because of the FDA’s notoriously lax follow-up and in part because drugmakers tend to drag their feet. When the drug is in use and profits are good, why would a manufacturer want to find out that a lucrative blockbuster is a failure?

Historically, so far, most of the new drugs that have received accelerated approval treat serious malignancies.

And follow-up studies are far easier to complete when the disease is cancer, not a neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s. In cancer, “no benefit” means tumor progression and death. The mental decline of Alzheimer’s often takes years and is much harder to measure. So years, possibly decades, later, Aduhelm studies might not yield a clear answer, even if Biogen manages to enroll a significant number of patients in follow-up trials.

Now that Aduhelm is shipping into the marketplace, enrollment in the required follow-up trials is likely to be difficult, if not impossible. If your loved one has Alzheimer’s, with its relentless diminution of mental function, you would want the drug treatment to start right now. How likely would you be to enroll and risk placement in a placebo group?

The FDA gave Biogen nine years for follow-up studies but acknowledged that the timeline was “conservative.”

Even when the required additional studies are performed, the FDA historically has been slow to respond to disappointing results.

In a 2015 study of 36 cancer drugs approved by the FDA, only five ultimately showed evidence of extending life. But making that determination took more than four years, and over that time the drugs had been sold, at a handsome profit, to treat countless patients. Few drugs are removed.

It took 17 years after initial approval via the accelerated process for Mylotarg, a drug to treat a form of leukemia, to be removed from the market after subsequent trials failed to show clinical benefit and suggested possible harm. (The FDA permitted the drug to be sold at a lower dose, with less toxicity.)

Avastin received fast-track approval as a breast cancer treatment in 2008, but three years later the FDA revoked the approval after studies showed the drug did more harm than good in that use. (It is still approved for other, generally less common cancers.)

In April, the FDA said it would be a better policeman of cancer drugs that had come to markets via accelerated approval. But time — as in delays — means money to drug manufacturers.

A few years ago, when I was writing a book about the business of U.S. medicine, a consultant who had worked with pharmaceutical companies on marketing drug treatments for hemophilia told me the industry referred to that serious bleeding disorder as a “high-value disease state,” since the medicines to treat it can top $1 million a year for a single patient.

Aduhelm, at $56,000 a year, is a relative bargain — but hemophilia is a rare disease, and Alzheimer’s is terrifyingly common. Drugs to combat it will be sold and taken. The crucial studies that will define their true benefit will take many years or may never be successfully completed. And from a business perspective, that doesn’t really matter.

Elisabeth Rosenthal, M.D., is editor of Kaiser Health News.

David Warsh: From eugenics to molecular biology

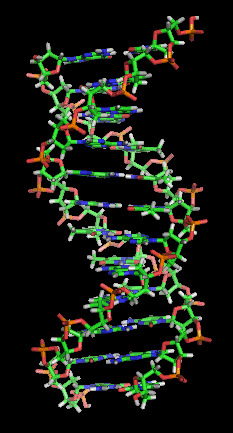

Representation of the now famous “Double Helix’’: Two complementary regions of nucleic acid molecules will bind and form a double helical structure held together by base pairs.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was so long ago that I can no longer remember with any precision the pathways along which the book started me towards economic journalism. What I know with certainty is that The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA (Athenaeum), by James Watson, changed my life when I read it, not long after it was first published, in 1968. Watson’s intimate account of his and Francis Crick’s race with Linus Pauling in 1953 to solve the structure of the molecule at the center of hereditary transmission was thrilling in all its particulars. I went into college one way and came out another, with a durable side-interest in molecular biology.

Thus when Horace Freeland Judson’s The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Modern Biology (Simon and Schuster), came along, in 1979, I marveled at Judson’s much more expansive collective portrait of the age. And when Lily Kay’s The Molecular Vision of Life: Caltech, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Rise of the New Biology (Oxford) came out in, in 1993, I was quite taken by the institutional background it supplied.

Kay told the story of how the mathematician Warren Weaver in the 1930s decisively backed the Rockefeller Foundation away from its ill-considered funding backing of the fringes of the eugenics movement – human engineering through controlled breeding – by initiating “a concerted physiochemical attack on [discovering the nature of] the gene… at the moment in history when it became unacceptable to advocate social control based on crude eugenic principles and outmoded racial theories.”

Not until 1938 would Weaver describe his campaign as “molecular biology.” In the dozen years after 1953, Nobel prizes were awarded to 18 scientists for investigation of the nature of the gene, all but one of them funded by the Rockefeller Foundation under Weaver’s direction.

For the past couple of weeks I have been reading Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race (Simon & Schuster, 2021), by Walter Isaacson. Doudna, you may remember (pronounced Dowd-na), shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry last autumn with collaborator Emmanuelle Charpentier “for the development of a method of genetic editing” known as the CRISPR/Cas 9 genetic scissors. The COVID pandemic prevented the journeys to Stockholm that laureates customary make to deliver lectures and accept prizes. Medalists will be recognized at some later date. At that point, expect the significance of the new code-editing technologies to be emphasized. The new know-how recognized in 2020 Prize in Chemistry is probably the most important breakthrough since the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine went to Crick, Watson and Maurice Wilkins, in 1962. Instead of the sterilization and other forceful measures envisaged by the eugenics movement, CRISPR promises to gradually eliminate hereditary disease.

Three themes emerge from Code Breaker. The first is how much has changed with respect to gender, in biological science at least. X-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin died in 1958, four years before she might have shared the prize. (Dead persons are not eligible for the award.) She was cruelly disparaged in Watson’s book, despite the fact that her photographs were crucial to the discovery of the helical structure of the gene.

Opportunities for female scientists had begun to open up by the time that The Eighth Day was published, but women hadn’t yet reached levels of professional accomplishment such that their photographs would appear except rarely in pages dominated by White males. Doudna, born in 1964, and Charpentier, born in 1968, encountered abundant opportunities.

A second theme, less stressed, underscores the extent to which the tables have turned over the last century with respect to the importance attached by scientists to race. Strongly held view about the dispersion of genetic endowments across various populations are nothing new, but, as The New York Times put it a couple of years ago, “It has been more than a decade since James D. Watson, a founder of modern genetics, landed in a kind of professional exile by suggesting that black people are intrinsically less intelligent than whites.”

A third theme, the main story, is Doudna’s decision, as a graduate student in the 1990s, to study the less-celebrated RNA molecule that performs work by copying DNA-coded information in order to build proteins in cells. All this is clearly explained in Isaacson’s book, in relatively short chapters and sub-sections. The effect of this mosaic technique is to briskly move the story along.

After many twists and turns, Doudna and Charpentier showed in June 2012 that “clustered regularly interspersed palindromic repeats” (hence the easy-to-remember-and- pronounce acronym CRISPR), “Cas9” being a particular associated enzyme that did the cutting work, could be made to cut and replace fragments of genes work in a test tube. Within six months, five different papers appeared showing that such scissors would also work in live animal cells.

The famed Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, in Cambridge, where much important biomedical and genomic research is conducted.

An epic patent battle ensued, involving claims to various ways in which CRISPR systems could be used in different sorts of kinds of organisms. A nearly metaphysical argument developed: Once Doudna and Charpentier demonstrated that the technique would work on bacteria, was it “obvious” that it would work in human cells? Rival claimants included Doudna, of the University of California at Berkeley; Charpentier, of Umeå University, Sweden; geneticist George Church, of the Harvard Medical School; and molecular biologist Feng Zhang, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

Church and Zhang are colorful characters with powerful minds and different scientific backgrounds. Their complicated competition with Doudna and Charpentier is said to reprise the race of Watson and Crick with Pauling forty years before. Well-disposed toward all four principals, author Isaacson spends a fair amount of effort interpreting their rival claims. At the end of the book, he expresses the hope that Zhang and Church might one day share a Nobel Prize in Medicine for their CRISPR work.

If there is a better all-around English-language journalist of the last fifty years than Isaacson, I don’t know who that might be. Born in 1952, he grew up in New Orleans, went to Harvard College and then Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar, before beginning newspaper work. He joined Time magazine as a political reporter in 1978; by 1996 he was its editor. To that point he had written two books (the first with Evan Thomas): The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made; (1986); and Kissinger: A Biography (1992).

In 2001 Isaacson left Time to serve as CEO of CNN. Eighteen months later he was named president of the Aspen Institute. There followed, among other books, biographies of Benjamin Franklin (2003), Albert Einstein (2007), Steve Jobs (2011) and Leonardo da Vinci (2017). He resigned from the Aspen Institute in 2017 to become a professor of American History and Values at Tulane University.

As editor of Time, Isaacson took a call in 2000 from Vice President Al Gore, asking on behalf of President Clinton that the visage of National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins be added to that of biotech entrepreneur J. Craig Venter on the cover of a forthcoming issue. A crash program to sequence the human genome was threatening to break apart after the abrasive Venter devised a cheaper means and formed a private company.

Isaacson consulted his sources, including Broad Institute president Eric Lander, a friend from Rhodes Scholar days, and complied. Science journalist Nicholas Wade wrote the story. At least since then, Isaacson has been involved at the highest levels in the story of molecular biology. He is uniquely well-qualified to describe the most recent segment of its arc, and, in the second half of the book, to lay out the many thorny social choices that lie ahead.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran. © 2021 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

Walter Isaacson

Can't you do better?

— Photo by Maurice van Bruggen

“What are you saying? That you want

eternal life? Are your thoughts really

as compelling as all that?…”

— From “Field of Flowers,’’ by Louise Gluck (born 1943). The winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature for her poems, she lives in Cambridge, Mass., and is writer in residence at Yale.

In Garden in the Woods, a 45-acre woodland botanical garden, at 180 Hemenway Rd., Framingham, Mass. It is the headquarters of The Native Plant Trust, and is open to visitors between April 14 and Oct. 15.

'Materializing the medium's memory'

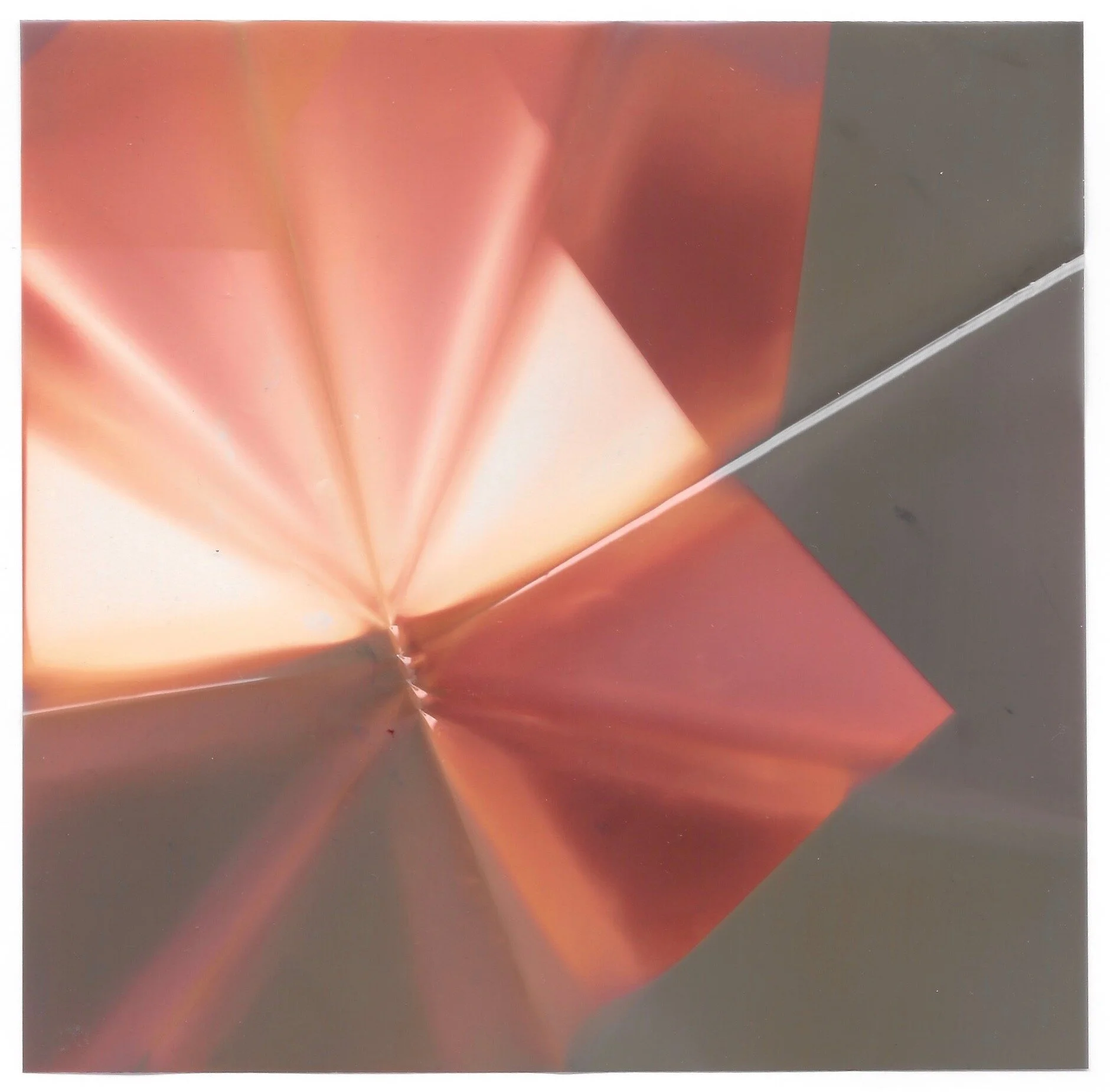

Image from ‘‘LUCID,’’ artist Exeter, N.H.-based Shaina Gates’s show from April 15 to May 15 at Gallery 263, Cambridge

The gallery says:

“This exhibition reflects the artist’s interest in the transfer and translation of images across surfaces, systematized processes, and theories related to dimensionality and the organization of space. In ‘LUCID,’’ a body of lumen prints on both paper and film are on view. The works in ‘LUCID’, which conjure a joy similar to what one may experience when looking through a kaleidoscope, map the physical experience of how the prints were systematically folded by the artist, materializing the medium’s memory as a visible record. In this way, the material becomes lucid.’’

Downtown Exeter, N.H.

Then and now: View over the Charles River

View of Boston from Cambridge. Top, in the early ‘50’s; bottom, last year

New England Council’s new virtual networking series

The New England Ensign, one of several flags historically associated with New England. This flag was used by colonial merchant ships sailing out of New England ports, 1686 – c. 1737.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

The New England Council is pleased to announce the launch of our new virtual networking series, Council Connections. We have heard from many members that one aspect of the Council that they have missed the most during the pandemic when in-person gatherings are not possible is the opportunity to network with fellow Council members across different industries and throughout the region. During this hour-long program, you will have the opportunity to meet and converse with other Council members in a series of smaller, randomly assigned group breakout sessions. Please note that due to technological constraints, capacity for this program is limited, however if there is interest, we hope to hold these sessions regularly.

How it will work:

The session will be conducted using Zoom. We strongly encourage you to connect on a desktop, laptop, or tablet with video enabled.

All participants will join the meeting and first be placed in a large general session, just like any other Zoom meeting.

Once all participants have joined the general session, Jim Brett will welcome everyone and give some brief opening remarks.

There will then be a series of four, 10-minute breakout sessions. During the breakout sessions, participants will be randomly placed into a smaller group meeting of five people total. During the 10-minute session, you will have the opportunity to converse with and get to know those in your breakout room.

Between each session, all participants will return briefly to the general session before being randomly placed in the next breakout session.

We will provide all participants with the full list of program participants including email addresses so that you are able to easily follow up with anyone you meet during the networking program.

Please note that the breakout session participants are randomly selected are we are not able to honor requests to connect with specific individuals. However, if there is someone you are interested in meeting, our staff is happy to help facilitate a connection separate from this event.

While these sessions will be open to all Council members across various industries, we are also considering some sector specific networking programs for our various policy committees.

We hope you will join us for the first Council Connections program, on Tuesday, February 9, 2021, from 1:00 – 2:00 p.m.

View of Cambridge, Mass., home of both Harvard and MIT and, as a result, a high concentration of startups in general and technology companies in particular

Heroic trees

“Willow Heights Trail #2’’’ (gouache on panel), by Vicki Kocher Paret, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Jan 8-31

The Cambridge-based painter says:

"My hero: nature, trees, pretty much the natural world. It has the power to support and heal the environment, and provide peace and spiritual healing with its endless diversity and beauty. It inspires and I strive to capture these powers in my paintings."

Jill Richardson: How do we get skeptics to get COVID shots?

U.S. airman Ramón Colón-López receives Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center this month.

Via OtherWords.org

With the new COVID-19 vaccine available, Dr. Anthony Fauci says Americans can begin to achieve herd immunity by next summer. Herd immunity occurs when so many people are immune to the virus that it can’t spread, because an infected person won’t have anyone left to spread it to.

Yet as of last month, four in ten Americans said they definitely or probably won’t get the vaccine (although about half of that group said they would consider it once a vaccine became available and they could get more information about it).

Why, after living in quarantine for almost 10 months while the economy and our mental health crashes around us, after over 300,000 Americans are dead, is getting the vaccine even a question?

There are two ways to approach this question. The first is to dismiss it: Call vaccine skeptics derogatory names, post memes on social media about how stupid they are, and make rules requiring the vaccine.

The second way to approach the question is to try to understand vaccine skepticism in order to address Americans’ concerns.

Sociologist Jennifer Reich tied vaccine refusal to messages that treat health like a personal project, in which consumers must exercise their own discretion, and a culture of individualism in a world where there is not enough of anything to go around — jobs, money, health care, etc.

In this view, everyone must look out for themselves so they can get ahead, and that’s more important than doing your part to achieve herd immunity for our collective wellbeing.

Reich’s research on anti-vaxxers comes from before the current pandemic. She studied parents who refused to vaccinate their children for preventable diseases like measles. But it’s still worth considering in this new context. Reich believes it is unsurprising that some people do treat vaccines like a consumer choice and disregard that when they decline a vaccine, they endanger others too.

Another take on COVID vaccine refusal comes from Zakiya Whatley and Titilayo Shodiya, who are both women of color with PhDs in natural sciences. They focus on Black, Latinx and indigenous communities, who often distrust doctors. Their suspicion is not unfounded, given how much racism in medicine has harmed people of color, historically and in the present.

Scientists hold the power to define what is true and what is not in a way that non-scientists do not. Consider the power relations within medicine: When a patient goes to the doctor because they are ill, the doctor assesses their symptoms, makes a diagnosis, and prescribes a treatment.

Scientists determine what is recognized as a diagnosis and which treatments are available. Powerful financial interests (like pharmaceutical and insurance companies) play a major role too. The patient’s power is more limited: they can look up their symptoms on WebMD, accept or refuse the treatment prescribed, or go to a different doctor.

Sometimes lay people react to being on the less powerful end of the relationship by simply refusing to believe scientists. They might resist by embracing conspiracy theories or “barstool biology” that uses the language of science but not the scientific method.

Natural scientists have done their part by creating vaccines that are safe and highly effective. To get people to take the vaccine, we need social science. We must learn how to rebuild trust with people who have lost it. And we will do that by listening to them and understanding them, not by calling them stupid.

Jill Richardson, a sociologist, is an OtherWords.org columnist.

Headquarters of a COVID-19 vaccine inventor and maker, Moderna, in Cambridge, Mass. Greater Boston is one of the world’s centers of biotechnology.