Liz Szabo: COVID's silver lining may be breakthroughs against other severe diseases

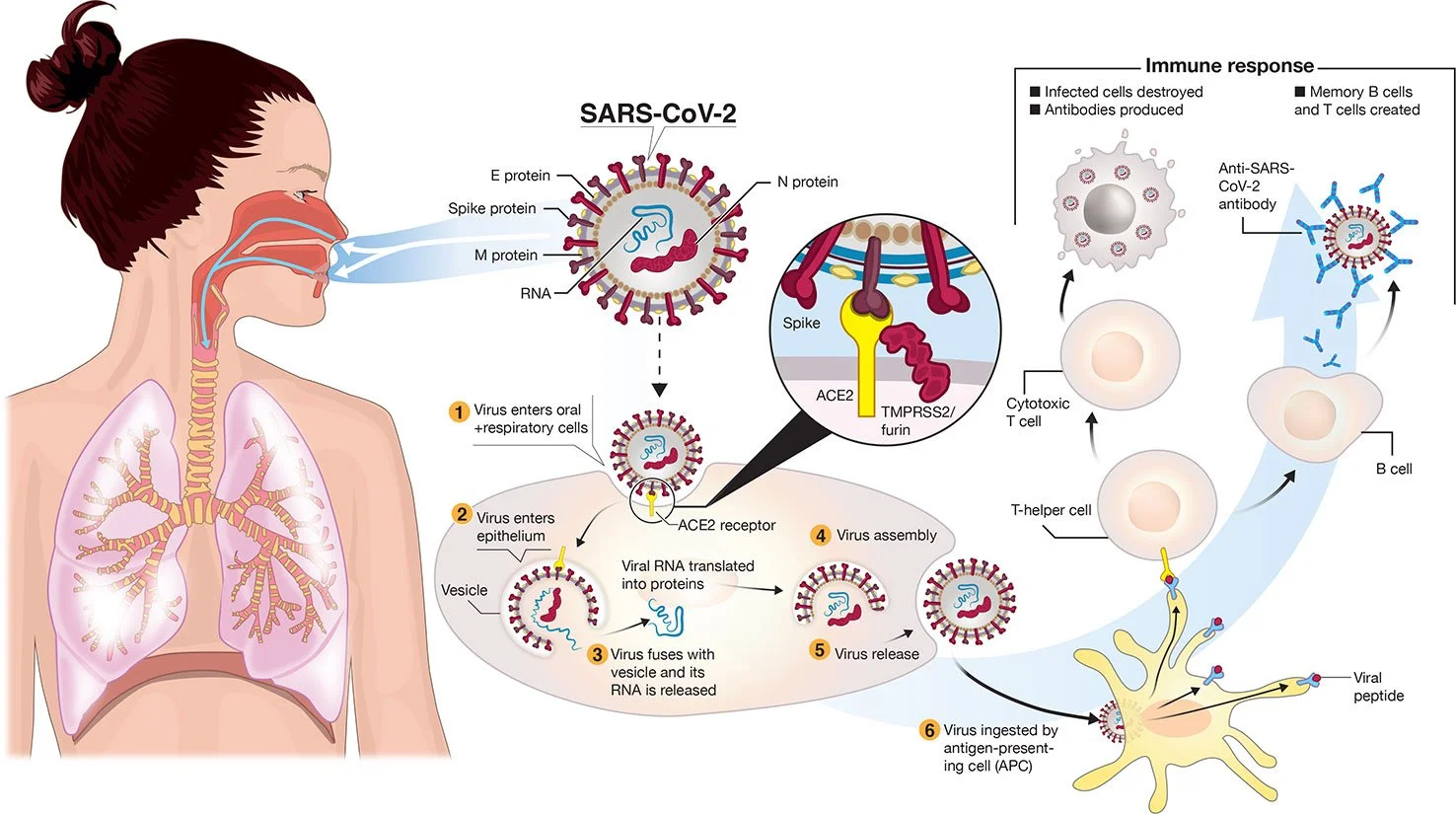

Transmission and life-cycle of SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19. 2/furin. A simplified depiction of the life cycle of the virus is shown along with potential immune responses elicited.

— Colin D. Funk, Craig Laferrière, and Ali Ardakani. Graphic by Ian Dennis - http://www.iandennisgraphics.com

“It’s not either/or. We’ve created this artificial dichotomy about how we think about these viruses. But we always put out a mixture of both” when we breathe, cough and sneeze.

— Dr. Michael Klompas, a professor at Harvard Medical School and infectious- disease doctor.

xxx

“There is a lot of frustration about being written off by the medical community, being told that it’s all in one’s head, that they just need to see a psychiatrist or go to the gym.’’

— Dr. David Systrom, a pulmonary and critical-care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston.

The billions of dollars invested in COVID-19 vaccines and research so far are expected to yield medical and scientific dividends for decades, helping doctors battle influenza, cancer, cystic fibrosis and far more diseases.

“This is just the start,” said Dr. Judith James, vice president of clinical affairs for the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. “We won’t see these dividends in their full glory for years.”

Building on the success of mRNA vaccines for covid, scientists hope to create mRNA-based vaccines against a host of pathogens, including influenza, Zika, rabies, HIV, and respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, which hospitalizes 3 million children under age 5 each year worldwide.

Researchers see promise in mRNA to treat cancer, cystic fibrosis and rare, inherited metabolic disorders, although potential therapies are still many years away.

Pfizer and Moderna worked on mRNA vaccines for cancer long before they developed covid shots. Researchers are now running dozens of clinical trials of therapeutic mRNA vaccines for pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, and melanoma, which frequently responds well to immunotherapy.

Companies looking to use mRNA to treat cystic fibrosis include ReCode Therapeutics, Arcturus Therapeutics, and Moderna and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, which are collaborating. The companies’ goal is to correct a fundamental defect in cystic fibrosis, a mutated protein.

Rather than replace the protein itself, scientists plan to deliver mRNA that would instruct the body to make the normal, healthy version of the protein, said David Lockhart, ReCode’s president and chief science officer.

None of these drugs is in clinical trials yet.

That leaves patients such as Nicholas Kelly waiting for better treatment options.

Kelly, 35, was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis as an infant and has never been healthy enough to work full time. He was recently hospitalized for 2½ months due to a lung infection, a common complication for the 30,000 Americans with the disease. Although novel medications have transformed the lives of most people with CF, they don’t work in 10% of patients. About one-third of patients who don’t benefit from the new medications are Black and/or Hispanic, said JP Clancy, vice president of clinical research for the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

“Nobody wants to be hospitalized,” said Kelly, who lives in Cleveland. “If something could decrease my symptoms even 10%, I would try it.”

Predicting Which COVID Patients Are Most Likely to Die

Ambitious scientific endeavors have provided technological windfalls for consumers in the past; the race to land on the moon in the 1960s led to the development of CT scanners and MRI machines, freeze-dried food, wireless headphones, water purification systems, and the computer mouse.

Likewise, funding for AIDS research has benefited patients with a variety of diseases, said Dr. Carlos del Rio, a professor of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine. Studies of HIV led to the development of better drugs for hepatitis C and cytomegalovirus, or CMV; paved the way for successful immunotherapies in cancer; and speeded the development of covid vaccines.

Over the past two years, medical researchers have generated more than 230,000 medical journal articles, documenting studies of vaccines, antivirals, and other drugs, as well as basic research into the structure of the virus and how it evades the immune system.

Dr. Michelle Monje, a professor of neurology at Stanford University, has found similarities in the cognitive side effects caused by COVID and a side effect of cancer therapy often called “chemo brain.” Learning more about the root causes of these memory problems, Monje said, could help scientists eventually find ways to prevent or treat them.

James hopes that computer technology used to detect COVID will improve the treatment of other diseases. For example, researchers have shown that cell-phone apps can help detect potential covid cases by monitoring patients’ self-reported symptoms. James said she wonders if the same technology could predict flare-ups of autoimmune diseases.

“We never dreamed we could have a PCR test that could be done anywhere but a lab,” James said. “Now we can do them at a patient’s bedside in rural Oklahoma. That could help us with rapid testing for other diseases.”

One of the most important pandemic breakthroughs was the discovery that 15 to 20 percent of patients over 70 who die of COVID have rogue antibodies that disable a key part of the immune system. Although antibodies normally protect us from infection, these “autoantibodies” attack a protein called interferon that acts as a first line of defense against viruses.

By disabling key immune fighters, autoantibodies against interferon allow the coronavirus to multiply wildly. The massive infection that results can lead the rest of the immune system to go into hyperdrive, causing a life-threatening “cytokine storm,” said Dr. Paul Bastard, a researcher at Rockefeller University.

The discovery of interferon-targeting antibodies “certainly changed my way of thinking at a broad level,” said E. John Wherry, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Institute for Immunology, who was not involved in the studies. “This is a paradigm shift in immunology and in COVID.”

Antibodies that disable interferon may explain why a fraction of patients succumb to viral diseases, such as influenza, while most recover, said Dr. Gary Michelson, founder and co-chair of Michelson Philanthropies, a nonprofit that funds medical research and recently gave Bastard its inaugural award in immunology.

The discovery “goes far beyond the impact of COVID-19,” Michelson said. “These findings may have implications in treating patients with other infectious diseases” such as the flu.

Bastard and colleagues have also found that one-third of patients with dangerous reactions to yellow fever have autoantibodies against interferon.

International research teams are now looking for such autoantibodies in patients hospitalized by other viral infections, including chickenpox, influenza, measles, respiratory syncytial virus, and others.

Overturning Dogma

For decades, public health officials created policies based on the assumption that viruses spread in one of two ways: either through the air, like measles and tuberculosis, or through heavy, wet droplets that spray from our mouths and noses, then quickly fall to the ground, like influenza.

For the first 17 months of the covid pandemic, the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said the coronavirus spread through droplets and advised people to wash their hands, stand 6 feet apart, and wear face coverings. As the crisis wore on and evidence accumulated, researchers began to debate whether the coronavirus might also be airborne.

Today it’s clear that the coronavirus — and all respiratory viruses — spread through a combination of droplets and aerosols, said Dr. Michael Klompas, a professor at Harvard Medical School and infectious disease doctor.

“It’s not either/or,” Klompas said. “We’ve created this artificial dichotomy about how we think about these viruses. But we always put out a mixture of both” when we breathe, cough, and sneeze.

Knowing that respiratory viruses commonly spread through the air is important because it can help health agencies protect the public. For example, high-quality masks, such as N95 respirators, offer much better protection against airborne viruses than cloth masks or surgical masks. Improving ventilation, so that the air in a room is completely replaced at least four to six times an hour, is another important way to control airborne viruses.

Still, Klompas said, there’s no guarantee that the country will handle the next outbreak any better than this one. “Will we do a better job fighting influenza because of what we’ve learned?” Klompas said. “I hope so, but I’m not holding my breath.”

Fighting Chronic Disease

Lauren Nichols, 32, remembers exactly when she developed her first covid symptoms: March 10, 2020.

It was the beginning of an illness that has plagued her for nearly two years, with no end in sight. Although Nichols was healthy before developing what has become known as “long COVID,” she deals with dizziness, headaches, and debilitating fatigue, which gets markedly worse after exercise. She has had shingles — a painful rash caused by the reactivation of the chickenpox virus — four times since her covid infection.

Six months after testing positive for COVID, Nichols was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis, or ME/CFS, which affects more than 1 million Americans and causes many of the same symptoms as COVID. There are few effective treatments for either condition.

In fact, research suggests that “the two conditions are one and the same,” said Dr. Avindra Nath, clinical director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, part of the National Institutes of Health. The main difference is that people with long COVID know which virus caused their illness, while the precise virus behind most cases of chronic fatigue is unknown, Nath said.

Advocates of patients with long COVID want to ensure that future research — including $1.15 billion in targeted funding from the NIH — benefits all patients with chronic, post-viral diseases.

“Anything that shows promise in long covid will be immediately trialed in ME/CFS,” said Jarred Younger, director of the Neuroinflammation, Pain and Fatigue Laboratory at the University of Alabama-Birmingham.

Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome have felt a kinship with long COVID patients, and vice versa, not just because they experience the same baffling symptoms, but also because both have struggled to obtain compassionate, appropriate care, said Nichols, vice president of Body Politic, an advocacy group for people with long COVID and other chronic or disabling conditions.

“There is a lot of frustration about being written off by the medical community, being told that it’s all in one’s head, that they just need to see a psychiatrist or go to the gym,” said Dr. David Systrom, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

That sort of ignorance seems to be declining, largely because of increasing awareness about long COVID, said Emily Taylor, vice president of advocacy and engagement at Solve M.E., an advocacy group for people with post-infectious chronic illnesses. Although some doctors still refuse to believe long covid is a real disease, “they’re being drowned out by the patient voices,” Taylor said.

A new study from the National Institutes of Health, called RECOVER (Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery), is enrolling 15,000 people with long covid and a comparison group of nearly 3,000 others who haven’t had covid.

“In a very dark cloud,” Nichols said, “a silver lining coming out of long covid is that we’ve been forced to acknowledge how real and serious these conditions are.”

Liz Szabo is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Barbara Ann Fenton-Fung: Broaden outreach to reach more in the urban core in the pandemic

Broad Street in Central Falls

While medical professionals stare down Round #2 of our COVID-19 nightmare, the arrival of a vaccine in Rhode Island is like the bright stars on top of our trees this holiday season. Indeed, it is a beacon of hope for so many whose loved ones have been afflicted by the disease and for those who have cared for those patients for the past 10 months.

So it is imperative that we learn from the bumps in the road in testing rollouts earlier this year. When negative national headlines surrounded such communities as Central Falls, where the consequences of socio-economic disparities created a horrific storm of disease transmission, government was on its heels when trying to right the ship to create buy-in for the vaccine's distribution and use in our very diverse communities.

This is particularly a challenge in urban-core neighborhoods, where there is a large non-native English-speaking population and where many use languages that do not use Latin-based alphabets. Very few and far between are the official government communications in Khmer script for our Cambodian residents, or Chinese pictographs, or Arabic for our neighbors from the Middle East. My own mother-in-law's native language is Cantonese, and I can remember her not quite understanding the full scope of COVID as it hit Rhode Island. But once my husband, Allan Fung, who had to deal with some of these issues as Cranston’s mayor, laid it out in her native language, she became the biggest promoter of guidance from our public-health leaders. To have better outcomes, we need to go the extra mile in different languages via digital video communications, mailers and multilingual media entities to reach those we didn't reach the last time around.

And effective communications also include having the right messenger. That, in some cultures, may not be a government official. Indeed, the cultural aspects of medicine are often overlooked in the midst of a pandemic when time is of the essence. Yet revered religious leaders or well-known community organizers might be the best people to connect with marginalized communities and work through cultural hesitations towards medical treatments.

As we look toward mass vaccination, let’s start now in connecting with these influencers in our faith communities and social organizations to create a more cohesive and effective community response. Government officials need to engage with, and empower, other community leaders here, and not act as if they alone had the right answers.

We all can agree that 2020 was a year of challenges, including many that will stick around in 2021. As we enter the new year, we should vow to be smarter and more inclusive in our approach to beating the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure that we lift everyone, in communities from rich to poor, up and across the finish line.

Barbara Ann Fenton-Fung (MSPT) is a physical therapist, whose expertise includes the cultural aspects of medicine. She is also a Republican state representative-elect from Cranston.

Some COVID-19 symptoms

Victoria Knight: Inadequate data on efficacy of face masks

“We simply don’t have data to say this,” Andrew Lover, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

A popular social media post that’s been circulating on Instagram and Facebook since April depicts the degree to which mask-wearing interferes with the transmission of the novel coronavirus. It gives its highest “contagion probability” — a very precise 70% — to a person who has COVID-19 but interacts with others without wearing a mask. The lowest probability, 1.5%, is when masks are worn by all.

The exact percentages assigned to each scenario had no attribution or mention of a source. So we wanted to know if there is any science backing up the message and the numbers — especially as mayors, governors and members of Congress increasingly point to mask-wearing as a means to address the surges in coronavirus cases across the country.

Doubts About The Percentages

As with so many things on social media, it’s not clear who made this graphic or where they got their information. Since we couldn’t start with the source, we reached out to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to ask if the agency could point to research that would support the graphic’s “contagion probability” percentages.

“We have not seen or compiled data that looks at probabilities like the ones represented in the visual you sent,” Jason McDonald, a member of CDC’s media team, wrote in an email. “Data are limited on the effectiveness of cloth face coverings in this respect and come primarily from laboratory studies.”

McDonald added that studies are needed to measure how much face coverings reduce transmission of COVID-19, especially from those who have the disease but are asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic.

Other public health experts we consulted agreed: They were not aware of any science that confirmed the numbers in the image.

“The data presented is bonkers and does not reflect actual human transmissions that occurred in real life with real people,” Peter Chin-Hong, a professor of medicine at the University of California-San Francisco, wrote in an email. It also does not reflect anything simulated in a lab, he added.

Andrew Lover, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, agreed. He had seen a similar graphic on Facebook before we interviewed him and done some fact-checking on his own.

“We simply don’t have data to say this,” he wrote in an email. “It would require transmission models in animals or very detailed movement tracking with documented mask use (in large populations).”

Because COVID-19 is a relatively new disease, there have been only limited observational studies on mask use, said Lover. The studies were conducted in China and Taiwan, he added, and mostly looked at self-reported mask use.

Research regarding other viral diseases, though, indicates masks are effective at reducing the number of viral particles a sick person releases. Inhaling viral particles is often how respiratory diseases are spread.

SOURCES:

ACS Nano, “Aerosol Filtration Efficiency of Common Fabrics Used in Respiratory Cloth Masks,” May 26, 2020

Associated Press, “Graphic Touts Unconfirmed Details About Masks and Coronavirus,” April 28, 2020

BMJ Global Health, “Reduction of Secondary Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Households by Face Mask Use, Disinfection and Social Distancing: A Cohort Study in Beijing, China,” May 2020

Email interview with Andrew Noymer, associate professor of population health and disease prevention, University of California-Irvine, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Jeffrey Shaman, professor of environmental health sciences and infectious diseases, Columbia University, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Linsey Marr, Charles P. Lunsford professor of civil and environmental engineering, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Peter Chin-Hong, professor of medicine, and George Rutherford, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics, University of California-San Francisco, June 29, 2020

Email interview with Werner Bischoff, medical director of infection prevention and health system epidemiology, Wake Forest Baptist Health, June 30, 2020

Email statement from Jason McDonald, member of the media team, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 29, 2020

The Lancet, “Physical Distancing, Face Masks, and Eye Protection to Prevent Person-to-Person Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” June 1, 2020

Nature Medicine, “Respiratory Virus Shedding in Exhaled Breath and Efficacy of Face Masks,” April 3, 2020

Phone and email interview with Andrew Lover, assistant professor of epidemiology, University of Massachusetts Amherst, June 29, 2020

Reuters, “Partly False Claim: Wear a Face Mask; COVID-19 Risk Reduced by Up to 98.5%,” April 23, 2020

The Washington Post, “Spate of New Research Supports Wearing Masks to Control Coronavirus Spread,” June 13, 2020

One recent study found that people who had different coronaviruses (not COVID-19) and wore a surgical mask breathed fewer viral particles into their environment, meaning there was less risk of transmitting the disease. And a recent meta-analysis study funded by the World Health Organization found that, for the general public, the risk of infection is reduced if face masks are worn, even if the masks are disposable surgical masks or cotton masks.

The Sentiment Is On Target

Though the experts said it’s clear the percentages presented in this social media image don’t hold up to scrutiny, they agreed that the general idea is right.

“We get the most protection if both parties wear masks,” Linsey Marr, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech who studies viral air droplet transmission, wrote in an email. She was speaking about transmission of COVID-19 as well as other respiratory illnesses.

Chin-Hong went even further. “Bottom line,” he wrote in his email, “everyone should wear a mask and stop debating who might have [the virus] and who doesn’t.”

Marr also explained that cloth masks are better at outward protection — blocking droplets released by the wearer — than inward protection — blocking the wearer from breathing in others’ exhaled droplets.

“The main reason that the masks do better in the outward direction is that the droplets/aerosols released from the wearer’s nose and mouth haven’t had a chance to undergo evaporation and shrinkage before they hit the mask,” wrote Marr. “It’s easier for the fabric to block the droplets/aerosols when they’re larger rather than after they have had a chance to shrink while they’re traveling through the air.”

So, the image is also right when it implies there is less risk of transmission of the disease if a COVID-positive person wears a mask.

“In terms of public health messaging, it’s giving the right message. It just might be overly exact in terms of the relative risk,” said Lover. “As a rule of thumb, the more people wearing masks, the better it is for population health.”

Public health experts urge widespread use of masks because those with COVID-19 can often be asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic — meaning they may be unaware they have the disease, but could still spread it. Wearing a mask could interfere with that spread.

Our Ruling

A viral social media image claims to show “contagion probabilities” in different scenarios depending on whether masks are worn.

Experts agreed the image does convey an idea that is right: Wearing a mask is likely to interfere with the spread of COVID-19.

But, although this message has a hint of accuracy, the image leaves out important details and context, namely the source for the contagion probabilities it seeks to illustrate. Experts said evidence for the specific probabilities doesn’t exist.

We rate it Mostly False.

Victoria Knight is a journalist at Kaiser Health News.

Partly non-virus-related!

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

With many newspapers shrinking unto death, all they seem to have room for is COVID-19 stuff; there are many other important things happening around the world that aren’t being reported. As the late Bill Kreger, a news editor to whom I reported at The Wall Street Journal once observed: “Sometimes the most important story starts out at the bottom of Page 37.’’ What might we be missing?

Well, The Boston Guardian reports that property and violent crime is down in its circulation area (the Back Bay, Beacon Hill , downtown and Fenway) this year. But maybe that’s a virus-related story? As newly unemployed people run out of money will property crimes increase?

Then there’s an inspiring little item from the March 24 Wall Street Journal: Voters in Mexican border city of Mexicali have admirably told the U.S. company Constellation Brands not to complete a $1.4 billion brewery there because the facility would take so much water that it could jeopardize the irrigation-dependent agriculture in the region.

In other heartening, if mostly symbolic, news, the U.S. has indicted Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro and some sidekicks for drug trafficking and is offering $15 million to those who aid his capture. Don’t expect Maduro to appear any time soon in a federal court, but the move is apt to make him nervous.

And there’s the important unhappy news that the world’s greatest coral reef, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, had just suffered another mass bleaching caused by global warming, whose associated increase in carbon dioxide makes sea water more acidic. For more information, please hit this link.