Llewellyn King: The ‘service’ sector’s assault on its customers

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The wreckage from COVID-19 continues to litter our lives. We work differently, play differently and are entertained differently.

For all I know, romance isn’t how it was. How can it be? So many fell in love, or just got into dating, at work. Zooming at home doesn’t quite cut it.

Customer service of all kinds has been laid waste. Excuse the bitter laughter, but what was for a while called the service economy was sent packing by COVID, as companies in droves found out that they could serve less and get the same money.

Let us start with the airlines. If you have had the misfortune to take a flight, you are as likely suffering from your own brand of PTSD. You may get counseling at the YMCA or find a support group online.

First off, booking online. This isn’t for the faint of heart. Some people aren’t computer-wise but they shouldn’t think that they can call the airlines and get help. That is so last century. You had best find one of the few independent travel agents still in business. This person, you soon learn, will book you on Expedia and charge you a fee for doing the obvious. What price hassle reduction?

The Transportation Security Administration infuriates us all. More so since COVID erupted, because many people don’t want to put on the TSA uniform when they can get work where everyone doesn’t hate them.

It didn’t have to be this way. If the airlines and their friendly regulator, the Federal Aviation Administration, had just put locks on cockpit doors after the first hijackings in the 1950s, chances are that there would have been no 9/11, no TSA, and I could keep my shoes on and TSA hands off. If you like being patted down, get a dog.

Then there is the cash conundrum. On bank notes, it says, “This note is legal tender for all debts public and private.” Not anymore. Try using cash at the airline counter. Not since COVID do they take it. I saw a sad situation when a young woman, already pulled up short for having to pay for checking her backpack, was told to convert her cash into a credit voucher at a machine, which has suddenly appeared near the check-in — for another fee, of course. Friendly skies, eh?

Once you have paid extra for luggage, extra for a marginally larger seat, extra to board early, and extra for Wi-Fi, you might think all is well, and it is time for the boarding scrum. No way. The flight is canceled. No pilot. To my mind, that would be a critical job in aviation, and if you have the temerity to run an airline, you might want to have a few extra pilots. Soon, the airlines may ask passengers to pop forward and handle the controls — for a fee, of course.

Banks responded to COVID by closing branches and putting ATM machines in parking lots.

Maybe you have tried to pay your credit-card bill when it is already in arrears because the bank-card company has stopped sending out paper bills without telling you? Next thing is that they are calling you in the middle of dinner to tell you that your credit is being damaged by your being tardy paying. “No problem,” you tell the recorded voice, which has just ruined dinner.

Don’t call them unless you have half a day to spare because you are aren’t supposed to call the bank and speak to anyone anymore. It used to be a person, but they are now “representatives” who have just crossed the border and sent to a call center by a Southern governor. They know enough English to tell you that they are trying to collect a debt, not solve your problem because you don’t have the paper bill.

You give up. You don’t care about your credit score anymore. You read this person the information from your check and ask them to take the money and do something unsanitary with their card. Over? Hell no. Later, you will get a letter from the “customer relations team” telling you impolitely that your check didn’t clear because you gave them the wrong routing number.

You may find it tough to get someone to clean up your hotel room.

— Photo by JIP

Hotels also have jumped at the opportunity to stick it to you since the COVID outbreak. You have to beg to have your room cleaned, even though you pay hundreds of dollars a night. More begging for towels. When you complain about how you are being treated, they say this is for your safety due to COVID.

The hospitality industry is reeling from COVID. Yes. Reeling it in

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

White House Chronicle

— Photo by Jengod

Llewellyn King: The new normal will take time, not politics

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Loud detonations are going off in the economy. When the debris settles, new realities will emerge. We won’t return to the status quo ante, although that is what politicians like to promise.

After great cataclysmic events — wars, natural disasters or the impact of new technologies — we need to acknowledge the realities and find the opportunities.

The inflation that is shaking the world is the inflammation that arises as markets seek equilibrium — as markets always do.

The greatest disrupter has been the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ramifications of how it has reshaped economies and societies are still evolving. For example, will we need as much office space as we did pre-pandemic? Is the delivery revolution the new normal?

Russia’s war in Ukraine has added to the pandemic-caused changes before they have fully played out. They, in turn, were playing out against the larger imperatives of climate change, and the sweeping adjustments that are underway to head off climate disaster.

Some political actions have exacerbated the turbulence of the economic situation, but they aren’t the root causes, just additional economic inflammation. These include former president Donald Trump’s tariffs and President Biden’s mindless moves against pipelines, followed by attempts to lower gasoline prices, or wean us from natural gas while supplying more natural gas to Europe.

In the energy crisis (read shortage) of the 1970s, I invited Norman Macrae, the late, great deputy editor of The Economist, to give a speech at the annual meeting of The Energy Daily, which I had created in 1973 — and which was then a kind of bible to those interested in energy and the crisis. Macrae, who had a profound influence in making The Economist a power in world thinking, shared a simple economic verity with the audience: “Llewellyn has invited me here to discuss the energy crisis. That is simple: the consumption will fall, and the supply will increase. Poof! End of crisis. Now, can we talk about something interesting?”

Of the many, many experts I have brought to podiums around the world, never has one been as warmly received as Macrae. Not only did the audience stand and applaud, but many also climbed on their chairs and applauded. I’m not sure Washington’s venerable Shoreham Hotel had ever seen anything like that, at least not at a business conference.

In today’s chaotic situation with political accusations clashing with supply realities, the temptation is to find a political fix while the markets seek out the new balance. Politicians want to be seen to do something, no matter what, and before it has been established what needs to be done.

An example of this was Biden increasing the allowed amount of ethanol derived from corn and added to gasoline. It is so small an addition that it won’t affect the price at the pump, but it might affect the price of meat at the supermarket. Corn is important in raising cattle and feeding large parts of the world.

There is a global grain crisis as a result of Russia’s war in Ukraine, which is a huge grain producer. Parts of the world, especially Africa, face starvation. The last thing that is needed is to sop up American grain production by burning it as gasoline.

We are, in the United States, gradually moving from fossil fuels to renewables, but this is going to move our dependence offshore, and has the chance of creating new cartels in precious metals and minerals.

Essential to this move is the lithium-ion battery, the heart of electric vehicles and battery storage for renewables, and its tenuous supply chain. Lithium has increased in price nearly 500 percent in one year. It is so in demand that Elon Musk has suggested he might get into the lithium mining business.

But lithium isn’t the only key material coming from often unstable countries: There is cobalt, mostly supplied from the Democratic Republic of the Congo; nickel, mostly sourced in Indonesia; and copper, where supply comes primarily from Chile.

Across the board, supplies will increase, and demand will decline. Equilibrium will arrive, but vulnerability won’t be eliminated. That is an emerging supply chain constant as the economy shifts to the new normal.

The aftershocks of the pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine will be felt for a long time — and endured as inflation.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Victoria Knight: No, your cotton face mask isn’t all that effective

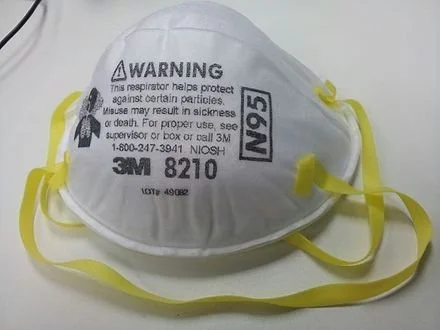

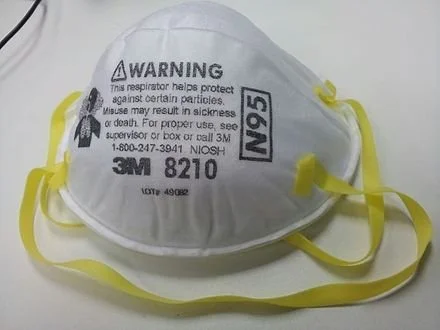

This N95 mask is highly effective.

— Photo by Banej

From Kaiser Health News in cooperation with PolitiFact

“From the perspective of knowing how covid is transmitted, and what we know about omicron, wearing a higher-quality mask is really critical to stopping the spread of omicron.’’

— Dr. Megan Ranney, academic dean for the School of Public Health at Brown University.

The highly transmissible omicron variant is sweeping the U.S., causing a huge spike in COVID-19 cases and overwhelming many hospital systems. Besides urging Americans to get vaccinated and boosted, public health officials are recommending that people upgrade from their cloth masks to higher-quality medical-grade masks.

But what does this even mean?

At a recent Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee hearing, top public health officials displayed different types of masking. Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, wore what appeared to be a surgical mask layered under a cloth mask, while Dr. Anthony Fauci, chief medical adviser to the president, wore what looked like a KN95 respirator.

(Dr. Wakensky was formerly chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.)

Some local governments and other organizations are offering their own policies. Los Angeles County, for instance, will require as of Jan. 17 that employers provide N95 or KN95 masks to employees. In late December, the Mayo Clinic began requiring all visitors and patients to wear surgical masks instead of cloth versions. The University of Arizona has banned cloth masks and asked everyone on campus to wear higher-quality masks.

Questions about the level of protection against COVID that masks provide — whether cloth, surgical or higher-end medical grade — have been a subject of debate and discussion since the earliest days of the pandemic. We looked into the question last summer. And as science changes and variants emerge with higher transmissibility, so do opinions.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has not updated its mask guidance since October, before the omicron variant emerged. That guidance doesn’t recommend the use of an N95 respirator but states only that masks should be at least two layers, well-fitting and contain a nose wire.

Multiple experts we consulted said that the current CDC guidance does not go far enough. They also agreed on another point: Wearing a cloth mask is better than not wearing a mask at all, but if you can upgrade — or layer cloth with surgical — now is the time.

Although cloth masks may appear to be more substantial than the paper surgical mask option, surgical masks as well as KN95 and N95 masks are infused with an electrostatic charge that helps filter out particles.

“From the perspective of knowing how COVID is transmitted, and what we know about omicron, wearing a higher-quality mask is really critical to stopping the spread of omicron,” said Dr. Megan Ranney, academic dean for the School of Public Health at Brown University.

A large-scale real-world study conducted in Bangladesh and published in December showed that surgical masks are more effective at preventing covid transmission than cloth masks.

So, one easy strategy to improve protection is to layer a surgical mask underneath cloth. Surgical masks can be bought relatively cheaply online and reused for about a week.

Ranney said she advises people who opt for layering to put the better-quality mask, such as the surgical mask, closest to your face, and put the lesser-quality mask on the outside.

If you’re really pressed for resources, Dr. Stephen Luby, a professor specializing in infectious diseases at Stanford University and one of the authors of the Bangladesh mask study, said surgical masks can be washed and reused, if finances are an issue. Nearly two years into the pandemic, such masks are cheap and plentiful in the U.S. and many retailers make them available free of charge to customers as they enter businesses.

“During the study, we told the participants they could wash the surgical masks with laundry detergent and water and reuse them,” Luby said. “You lose some effect of the electrostatic charge, but they still outperformed cloth masks.”

Still, experts maintain that wearing either a KN95 or an N95 respirator is the best protection against omicron, since these masks are highly effective at filtering out viral particles. The “95” in the names refers to the masks’ 95% filtration efficacy against certain-sized particles. N95 masks are regulated by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, while KN95s are regulated by the Chinese government and KF94s by the South Korean government.

Americans were initially urged not to buy either surgical or N95 masks early in the pandemic to ensure there would be a sufficient supply for health care workers. But now there are enough to go around.

So, if you have the resources to upgrade to an N95, a KN95 or a KF94 mask, you should absolutely do so, said Dr. Leana Wen, a professor of health policy and management at George Washington University. Although these models are more expensive and can be more uncomfortable, they are worth the investment for the safety they provide, she said.

“[Omicron is] a much more contagious virus, so there is a much lower margin of error in regards to the activities you were once able to do without getting infected,” Wen said. “We have to increase our protection in every way, because everything is riskier now.”

Wen also said that though these masks are characterized as one-use, unless you are in a health care setting, KN95s and N95s can be worn more than once. She uses one of her personal KN95s for more than a week at a time.

Another important thing to note is there are many counterfeit N95 and KN95 masks being sold online, so consumers must be careful when ordering them and be sure to get them only from a legitimate, trusted vendor.

The CDC maintains a list of NIOSH-approved N95 respirators. Wirecutter and The Strategist have both published guides to purchasing approved KN95 and KF94 masks. Ranney also recommends consulting the website Project N95 or engineer Aaron Collins’s “Mask Nerd” YouTube channel.

And remember, the risk of transmission depends not just on the mask you wear but also the masking practices of others in the room — so going into a meeting or restaurant where others are unmasked or wearing only cloth masks increases the odds of getting infected, no matter how careful you are. This chart demonstrates the huge differences.

Even with a mask upgrade, if you are still worried about omicron and, in particular, a serious case of , the No. 1 thing you can do to protect yourself is get vaccinated and boosted, said Dr. Neal Chaisson, an assistant professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

“There’s been a lot of talk about people who have been vaccinated getting omicron,” said Chaisson. “But I’ve been working in the ICU and probably 95% of the patients that we’re taking care of right now did not take the advice to get vaccinated.”

Victoria Knight is a Kaiser Health News reporter

vknight@kff.org, @victoriaregisk

Chris Powell: $75 million could be spent better; stop hysteria over COVID home testing

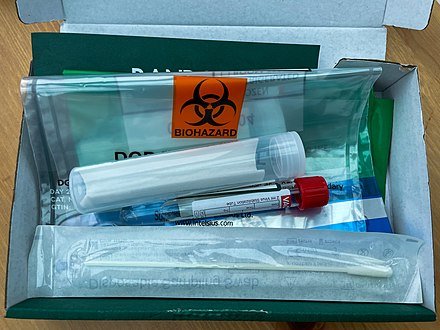

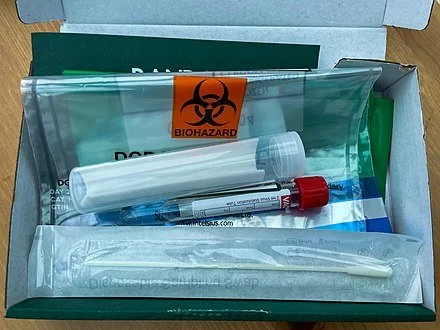

COVID-19 home test kit.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont could have found worse things to do with the $75 million in federal emergency aid he ordered distributed last week as a bonus to poor households receiving the state's earned-income tax credit. On average those households probably have suffered more financially from the long virus epidemic, since many of their breadwinners hold, or held, the service-sector jobs that were the first to be cut back or eliminated.

Complaints from Republicans that the bonuses mainly will reward a constituency of the governor's party, the Democrats, as his re-election campaign begins are not so compelling. For nearly everything government does rewards some political constituency, and state law already had identified the earned income tax credit constituency as deserving. If Connecticut ever again has a Republican administration, it will be unusual if Republican-leaning constituencies -- if only ordinary taxpayers -- are not rewarded too.

The governor's dispensing that $75 million is troublesome for different reasons, starting with the disregard for democratic procedure.

The governor's office says the federal law that sent the emergency money to the state authorizes his administration to spend it on expenses incurred because of the virus epidemic. But the state has been paying its earned income-tax-credit obligations all along. No payments by the government were cut because of the epidemic. While many recipients surely suffered losses because of the epidemic, it's unlikely that all did, and no one receiving the bonus will have to show evidence of such losses. The expenses to be reimbursed here are merely being assumed.

Additionally, $75 million is a lot of money for state government to dispense out of the blue at the command of just one official, an amount never formally appropriated by the General Assembly. Indeed, as Republican legislators note, state law already had determined how much was to be spent on the tax credit. The bonus created by the governor overrides that legislation.

Since he still exercises -- at least until February -- emergency powers to rule Connecticut by decree, the governor presumably could have rewritten the tax-credit law by himself to authorize the bonus. But he did not do so, perhaps because it might have emphasized his gathering unnecessary power to himself.

Republican legislators note that Connecticut faces many other compelling needs apart from those of the tax-credit recipients and that ordinary democracy first would have summoned the legislature or legislative leaders to discuss how to spend the $75 million. That's why the governor's high-handedness here is another argument for letting his emergency powers expire.

Having continued for two years, the virus epidemic is no longer an emergency. While the epidemic will wax and wane as epidemics do, government is fully aware of what combating it may require. Most of all, combating it may require more medical facilities and staff, and thus, to finance them, fewer raises for government employees, fewer stupid imperial wars and that $75 million that instead will be spent to expand the tax credit.

That money might build a few hospital wards and hire more doctors, nurses, and auxiliary staff. It might buy and distribute antivirals and vitamins.

If the tax-credit bonus can be construed as an expense of the epidemic, surely expanding medical capacity and services could be construed similarly. With so much free money flowing from Washington, the federal government probably wouldn't object if Connecticut chose to get more relevant.

After all, unlike the tax-credit bonus, increasing medical capacity might benefit everyone who got sick.

Meanwhile government's frantic efforts to distribute home testing kits for the virus and the public's frantic efforts to obtain them seem misplaced.

Surely quite without a test most people can tell if they are sick with symptoms like those attributed to the virus, and surely most people with such symptoms might have enough sense to get to a doctor or hospital quickly, especially since early treatment of the virus is crucial to defeating it.

The people lately waiting in long lines for a home test kit for the virus well may be putting themselves at greater risk of contracting it. The virus is bad enough. Test hysteria induced by government will make it worse.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Chris Powell: Amid most infections ever, time to reappraise pandemic policies

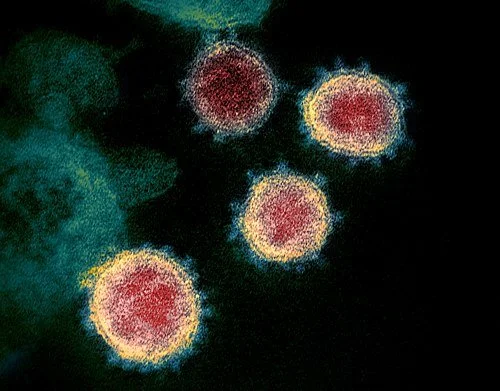

Graphic of COVID-19 infection by Colin D. Funk, Craig Laferrière, and Ali Ardakani.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut doesn't audit the performance of any of its major and expensive state government policies -- not education, not welfare, not urban -- but now would be a pretty good time for state government to audit its response to the virus epidemic.

For the epidemic has consumed nearly two years of state government's focus, impairing everything important -- commerce, schools, mental health, social order and basic liberty and democracy themselves -- only for all official efforts to fail to stop the spread of the virus. New daily confirmed cases in Connecticut in the last week averaged almost 4,000, the most yet, and weekly "virus-associated" deaths are double what they were only a few weeks ago.

An increase in infections might have been expected as colder weather pushed people closer together indoors and because of the holidays. But then a decline in infections also might have been expected because of the state population's high degree of vaccination and face-masking -- that is, might have been expected if vaccines and face-masking really work as promoted.

But even government and government-friendly medical officials admit that the vaccines are quickly losing effect. Needing frequent "boosters," they aren't half as good as traditional vaccines, and there is growing concern that too many "boosters" may damage the human immune system.

This doesn't mean that the vaccines and masks haven't helped or that the epidemic might not be worse without them. It means that another approach to the epidemic is necessary -- greater emphasis on therapies, of which there are many, and not only the antiviral pills just developed by pharmaceutical giants Pfizer and Merck, which, like the vaccines themselves, are not yet adequately tested and thus full of risk.

Even government-friendly medical authorities acknowledge the correlation between virus infection and deficiency in Vitamin D, the "sunshine vitamin," especially in people with dark complexions, and many authorities recommend strengthening the immune system with Vitamin D and C and zinc supplements. Natural and manmade antivirals and anticoagulants abound and many studies have found them effective against the virus, especially if administered soon after infection.

Unfortunately at the outset of the epidemic, when medicine did not understand the virus, patients were commonly told only to go home and take cold medicine and return to a doctor or hospital if their symptoms worsened. But when their symptoms worsened, it was often too late to save them.

Now treatment is more sophisticated. On any particular day infections in Connecticut may increase by thousands but hospitalizations and deaths by only a few. On some days infections soar but hospitalizations decline. Many infected people have no symptoms and nearly all people survive infection.

Even government-friendly medical authorities also acknowledge the correlation between virus fatalities and "co-morbidities" like obesity and diabetes, which most people could control.

Gov. Ned Lamont announced last week that state government soon will distribute, without charge, millions of masks and virus tests that can be taken at home. While the tests may be helpful, there is no shortage of masks and the virus penetrates them easily. It might be far better for state government to help people understand that their immune systems and general fitness may be defenses as good as if not better than masks and vaccines, and if state government distributed free immunity-boosting vitamins and supplements and even gym memberships.

State and local government officials and the medical authorities on whom they rely have done their best in circumstances that have no precedent in living memory. But their good intentions don't vindicate mistakes.

Despite lockdowns, mandatory masks, vaccines, "boosters," and damage to society that will not be repaired for many years, Connecticut and the country are facing more virus infections than ever. So government should start questioning its policies and assumptions about the epidemic, including the assumption that the epidemic is so deadly that combating it must take priority over all other objectives in life.

What isn't working needs to change, if only to set an example for the other things in state government that, after long experience, don't work except to sustain the government itself.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Liz Szabo: Tracking a mysterious COVID-related ailment in children (Copy)

Image of SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19:

MIS-C is thought to be caused by an unusual biological response to infection in certain children.

Like most other kids with COVID-19, Dante and Michael DeMaino seemed to have no serious symptoms.

Infected in mid-February, both lost their senses of taste and smell. Dante, 9, had a low-grade fever for a day or so. Michael, 13, had a “tickle in his throat,” said their mother, Michele DeMaino, of Danvers, Mass.

At a follow-up appointment, “the pediatrician checked their hearts, their lungs, and everything sounded perfect,” DeMaino said.

Then, in late March, Dante developed another fever. After examining him, Dante’s doctor said his illness was likely “nothing to worry about” but told DeMaino to take him to the emergency room if his fever climbed above 104.

Two days later, Dante remained feverish, with a headache, and began throwing up. His mother took him to the ER, where his fever spiked to 104.5. In the hospital, Dante’s eyes became puffy, his eyelids turned red, his hands began to swell and a bright red rash spread across his body.

Hospital staffers diagnosed Dante with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C, a rare but life-threatening complication of COVID-19 in which a hyperactive immune system attacks a child’s body. Symptoms — fever, stomach pain, vomiting, diarrhea, bloodshot eyes, rash and dizziness — typically appear two to six weeks after what is usually a mild or even asymptomatic infection.

More than 5,200 of the 6.2 million U.S. children diagnosed with COVID have developed MIS-C. About 80% of MIS-C patients are treated in intensive-care units, 20% require mechanical ventilation, and 46 have died.

Throughout the pandemic, MIS-C has followed a predictable pattern, sending waves of children to the hospital about a month after a covid surge. Pediatric intensive care units — which treated thousands of young patients during the late-summer delta surge — are now struggling to save the latest round of extremely sick children.

The South has been hit especially hard. At the Medical University of South Carolina Shawn Jenkins Children’s Hospital, for example, doctors in September treated 37 children with COVID and nine with MIS-C — the highest monthly totals since the pandemic began.

Doctors have no way to prevent MIS-C, because they still don’t know exactly what causes it, said Dr. Michael Chang, an assistant professor of pediatrics at Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, in Houston. All doctors can do is urge parents to vaccinate eligible children and surround younger children with vaccinated people.

Given the massive scale of the pandemic, scientists around the world are now searching for answers.

Although most children who develop MIS-C were previously healthy, 80% develop heart complications. Dante’s coronary arteries became dilated, making it harder for his heart to pump blood and deliver nutrients to his organs. If not treated quickly, a child could go into shock. Some patients develop heart rhythm abnormalities or aneurysms, in which artery walls balloon out and threaten to burst.

“It was traumatic,” DeMaino said. “I stayed with him at the hospital the whole time.”

Such stories raise important questions about what causes MIS-C.

“It’s the same virus and the same family, so why does one child get MIS-C and the other doesn’t?” asked Dr. Natasha Halasa of the Vanderbilt Institute for Infection, Immunology and Inflammation.

Doctors have gotten better at diagnosing and treating MIS-C; the mortality rate has fallen from 2.4% to 0.7% since the beginning of the pandemic. Adults also can develop a post-COVID inflammatory syndrome, called MIS-A; it’s even rarer than MIS-C, with a mortality rate seven times as high as that seen in children.

Although MIS-C is new, doctors can treat it with decades-old therapies used for Kawasaki disease, a pediatric syndrome that also causes systemic inflammation. Although scientists have never identified the cause of Kawasaki disease, many suspect it develops after an infection.

Researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital and other institutions are looking for clues in children’s genes.

In a July study, the researchers identified rare genetic variants in three of 18 children studied. Significantly, the genes are all involved in “removing the brakes” from the immune system, which could contribute to the hyper-inflammation seen in MIS-C, said Dr. Janet Chou, chief of clinical immunology at Boston Children’s, who led the study.

Chou acknowledges that her study — which found genetic variants in just 17% of patients — doesn’t solve the puzzle. And it raises new questions: If these children are genetically susceptible to immune problems, why didn’t they become seriously ill from earlier childhood infections?

Some researchers say the increased rates of MIS-C among racial and ethnic minorities around the world — in the United States, France and the United Kingdom — must be driven by genetics.

Others note that rates of MIS-C mirror the higher COVID rates in these communities, which have been driven by socio-economic factors such as high-risk working and living conditions.

“I don’t know why some kids get this and some don’t,” said Dr. Dusan Bogunovic, a researcher at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai who has studied antibody responses in MIS-C. “Is it due to genetics or environmental exposure? The truth may lie somewhere in between.”

A Hidden Enemy and a Leaky Gut

Most children with MIS-C test negative for COVID, suggesting that the body has already cleared the novel coronavirus from the nose and upper airways.

That led doctors to assume MIS-C was a “post-infectious” disease, developing after “the virus has completely gone away,” said Dr. Hamid Bassiri, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist and co-director of the immune dysregulation program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Now, however, “there is emerging evidence that perhaps that is not the case,” Bassiri said.

Even if the virus has disappeared from a child’s nose, it could be lurking — and shedding — elsewhere in the body, Chou said. That might explain why symptoms occur so long after a child’s initial infection.

Dr. Lael Yonker noticed that children with MIS-C are far more likely to develop gastrointestinal symptoms — such as stomach pain, diarrhea and vomiting — than the breathing problems often seen in acute covid.

In some children with MIS-C, abdominal pain has been so severe that doctors misdiagnosed them with appendicitis; some actually underwent surgery before their doctors realized the true source of their pain.

Yonker, a pediatric pulmonologist at Boston’s MassGeneral Hospital for Children, recently found evidence that the source of those symptoms could be the coronavirus, which can survive in the gut for weeks after it disappears from the nasal passages, Yonker said.

In a May study in The Journal of Clinical Investigation, Yonker and her colleagues showed that more than half of patients with MIS-C had genetic material — called RNA — from the coronavirus in their stool.

The body breaks down viral RNA very quickly, Chou said, so it’s unlikely that genetic material from a covid infection would still be found in a child’s stool one month later. If it is, it’s most likely because the coronavirus has set up shop inside an organ, such as the gut.

While the coronavirus may thrive in our gut, it’s a terrible houseguest.

In some children, the virus irritates the intestinal lining, creating microscopic gaps that allow viral particles to escape into the bloodstream, Yonker said.

Blood tests in children with MIS-C found that they had a high level of the coronavirus spike antigen — an important protein that allows the virus to enter human cells. Scientists have devoted more time to studying the spike antigen than any other part of the virus; it’s the target of covid vaccines, as well as antibodies made naturally during infection.

“We don’t see live virus replicating in the blood,” Yonker said. “But spike proteins are breaking off and leaking into the blood.”

Viral particles in the blood could cause problems far beyond upset stomachs, Yonker said. It’s possible they stimulate the immune system into overdrive.

In her study, Yonker describes treating a critically ill 17-month-old boy who grew sicker despite standard treatments. She received regulatory permission to treat him with an experimental drug, larazotide, designed to heal leaky guts. It worked.

Yonker prescribed larazotide for four other children, including Dante, who also received a drug used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. He got better.

But most kids with MIS-C get better, even without experimental drugs. Without a comparison group, there’s no way to know if larazotide really works. That’s why Yonker is enrolling 20 children in a small randomized clinical trial of larazotide, which will provide stronger evidence.

A month after Dante DeMaino left the hospital, doctors examined his heart with an echocardiogram to check for lingering heart damage from MIS-C. To his mother’s relief, his heart had returned to normal. Now, more than six months later, Dante is an energetic 10-year-old who has resumed playing hockey and baseball, swimming and rollerblading.

Rogue Soldiers

Dr. Moshe Arditi has also drawn connections between children’s symptoms and what might be causing them.

Although the first doctors to treat MIS-C compared it to Kawasaki disease — which also causes red eyes, rashes and high fevers — Arditi notes that MIS-C more closely resembles toxic shock syndrome, a life-threatening condition caused by particular types of strep or staph bacteria releasing toxins into the blood. Both syndromes cause high fever, gastrointestinal distress, heart muscle dysfunction, plummeting blood pressure and neurological symptoms, such as headache and confusion.

Toxic shock can occur after childbirth or a wound infection, although the best-known cases occurred in the 1970s and ’80s in women who used a type of tampon no longer in use.

Toxins released by these bacteria can trigger a massive overreaction from key immune system fighters called T cells, which coordinate the immune system’s response, said Arditi, director of the pediatric infectious diseases division at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

T cells are tremendously powerful, so the body normally activates them in precise and controlled ways, Bassiri said. One of the most important lessons T cells need to learn is to target specific bad guys and leave civilians alone. In fact, a healthy immune system normally destroys many T cells that can’t distinguish between germs and healthy tissue in order to prevent autoimmune disease.

In a typical response to a foreign substance — known as an antigen — the immune system activates only about 0.01% of all T cells, Arditi said.

Toxins produced by certain viruses and the bacteria that cause toxic shock, however, contain “superantigens,” which bypass the body’s normal safeguards and attach directly to T cells. That allows superantigens to activate 20% to 30% of T cells at once, generating a dangerous swarm of white blood cells and inflammatory proteins called cytokines, Arditi said.

This massive inflammatory response causes damage throughout the body, from the heart to the blood vessels to the kidneys.

Although multiple studies have found that children with MIS-C have fewer total T cells than normal, Arditi’s team has found an explosive increase in a subtype of T cells capable of interacting with a superantigen.

Several independent research groups — including researchers at Yale School of Medicine, the National Institutes of Health and France’s University of Lyon — have confirmed Arditi’s findings, suggesting that something, most likely a superantigen, caused a huge increase in this T cell subtype.

Although Arditi has proposed that parts of the coronavirus spike protein could act like a superantigen, other scientists say the superantigen could come from other microbes, such as bacteria.

“People are now urgently looking for the source of the superantigen,” said Dr. Carrie Lucas, an assistant professor of immunobiology at Yale, whose team has identified changes in immune cells and proteins in the blood of children with MIS-C.

Uncertain Futures

One month after Dante left the hospital, doctors examined his heart with an echocardiogram to see if he had lingering damage.

To his mother’s relief, his heart had returned to normal.

Today, Dante is an energetic 10-year-old who has resumed playing hockey and baseball, swimming and rollerblading.

“He’s back to all these activities,” said DeMaino, noting that Dante’s doctors rechecked his heart six months after his illness and will check again after a year.

Like Dante, most other kids who survive MIS-C appear to recover fully, according to a March study in JAMA.

Such rapid recoveries suggest that MIS-C-related cardiovascular problems result from “severe inflammation and acute stress” rather than underlying heart disease, according to the authors of the study, called Overcoming COVID-19.

Although children who survive Kawasaki disease have a higher risk of long-term heart problems, doctors don’t know how MIS-C survivors will fare.

The NIH and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have launched several long-term trials to study young covid patients and survivors. Researchers will study children’s immune systems to uncover clues to the cause of MIS-C, check their hearts for signs of long-term damage and monitor their health over time.

DeMaino said she remains far more worried about Dante’s health than he is.

“He doesn’t have a care in the world,” she said. “I was worried about the latest cardiology appointment, but he said, ‘Mom, I don’t have any problems breathing. I feel totally fine.’”

Liz Szabo is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

Chris Powell: Censorship undermines faith in medical science

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Science is wonderful. But it is not always settled. Sometimes the prevailing view in science is wrong, especially in medicine.

For 2,000 years a primary treatment for disease was bloodletting, sometimes administered with leeches. Doctors don't do that anymore.

A sedative called thalidomide was approved for use in European and other countries in the 1960s before it was found to cause birth defects.

The painkiller OxyContin, about which federal litigation is raging because of its highly addictive and even deadly properties, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1995. A year later an FDA official involved in OxyContin's approval was hired for a six-figure job at the drug's manufacturer, Stamford-based Purdue Pharma. Now the drug is blamed for thousands of deaths.

Medical mistakes are considered the third leading cause of death in the United States.

This week it was reported that the Food and Drug Administration had given full, formal approval to the Pfizer vaccine for the COVID-19 virus. But the FDA seems just to have extended the vaccine's authorization for emergency use.

Whereupon the acting commissioner of Connecticut's Public Health Department, Dr. Deidre Gifford, urged state residents to "trust the science" and get vaccinated.

It would have been fair to ask the commissioner: Whose science, exactly?

Of course, the commissioner wants people to follow the government's science. But there is other science, though it is increasingly subject to censorship by Internet sites and social media under government pressure.

Yes, quacks and cranks infiltrate discussion of the virus epidemic, as they always have infiltrated medicine. But the discussion also includes many highly credentialed doctors and scientists who -- at least before they voiced objections and concerns -- were renowned and honored in their fields. Some dispute the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines, while others dispute the vaccines' necessity, arguing that effective treatments for the virus are available.

These doctors and scientists could be mistaken. But censorship isn't how contrary assertions should be handled. Contrary assertions should be rebutted and learned from in the open.

This isn't happening because government, its allied medical authorities, and, it seems, journalism don't want a debate that might interfere with their preferred policy, vaccination. They are convinced that they have nothing to learn from the dissenters.

But the public isn't convinced. Many people are indifferent or even opposed to COVID-19 vaccination, and the policy advocated by many in government and the medical establishment is to stop trying to persuade people and start coercing them by denying them the right to live ordinary lives if they don't get vaccinated.

Much indifference and much opposition to vaccination are grounded in ignorance and contrariness. But not all.

Anyone paying attention to developments can perceive fair questions. For example, in regard to the Pfizer vaccine particularly, why is the government pushing it when it is still being tested and side-effects are still being discovered? Is this "approval" really a matter of safety or just political necessity?

And why is Israel's epidemic worsening, with a new wave of virus cases exploding to the level of the country's first wave even though Israel's population now may be the world's most thoroughly vaccinated -- primarily with the Pfizer vaccine?

The more what is said to be science relies on censorship and coercion, the less trust it will deserve.

Taliban religious police beating a woman in Kabul on Aug. 26, 2001.

- Photo by RAWA

If the thousands of Afghans who have swarmed the airport in Kabul for airlift out of the country really think that their country's new Taliban regime will be so terrible, where were they a few weeks ago when the U.S. military began withdrawing from the country?

Why did those thousands not enlist in the Afghan army in defense of the less totalitarian culture the U.S.-assisted government supported?

Those thousands might have formed a few useful military divisions, just as throughout history civilians were mobilized to defend cities under siege. Since women will be oppressed by the Taliban again, where was the Afghan army's 1st Women's Infantry Division? And how will Afghanistan's prospects be improved by removing so many people who oppose theocratic fascism?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

David Warsh: Article seems to have prompted Biden to order probe into idea that engineered COVID leaked from lab

Did COVID-19 escape from this complex?

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

There are few better-known brands in public service journalism than the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Founded in 1945 by University of Chicago physicists who helped produce the atom bomb, the organization adopted its famous clock logo two years later, with an original setting of seven minutes to midnight. Since then it has expanded the coverage of its monthly magazine and Web page to include climate change, biotech and other disruptive technologies.

In May, it published “The origin of COVID: Did people or nature open Pandora’s box at Wuhan?,” by veteran science journalist Nicholas Wade. Its appearance apparently prompted President Biden to ask U.S. intelligence agencies to reassess the possibility that a virus genetically engineered to become more dangerous had inadvertently escaped from a partly U.S.-funded laboratory in Wuhan, China, the Wuhan Institute of Virology. So when the Bulletin last week produced publisher Rachel Bronson, editor-in-chief John Mecklin and Wade for a one-hour q&a podcast, I tuned in.

Wade, too, has a substantial reputation. He served for many years as a staff writer and editor for Nature, Science and the science section of The New York Times. He is the author of many books as well, including The Nobel Duel: Two Scientists’ Twenty-one Year Race to Win the World’s Most Coveted Research Prize (1980), Before the Dawn: Recovering the Lost History of Our Ancestors (2006), and The Faith Instinct (2009).

True, Wade took a bruising the last time out, with Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race, and Human History (2014), which argued that human races are a biological reality and that recent natural selection has led to genetic difference responsible for disparities in political and economic development around the world. Some 140 senior human-population geneticists around the world signed a letter to The New York Times Book Review complaining that Wade had misinterpreted their work. But the editors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists would have taken that controversy into consideration.

The broadcast was what I expected. Publisher Bronson was proud of the magazine’s consistent attention to issues of lab safety; investigative journalist Wade, pugnacious and gracious by turns; editor-in-chief Mecklin, cautious and even-handed. When they were done, I re-read Wade’s article. I highly recommend it to anyone interested in the details. He is a most lucid writer.

What comes through is connection between the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Wuhan lab, one of several, in which NIH was funding a dangerous but essentially precautionary vaccine-development enterprise known as “gain-of-function” research (see Wade’s piece for a lucid explanation). Experts have known since the beginning that the virus was not a bioweapon. The only question was how it got loose in the world. What I find lacking in Wade’s account is context.

From the beginning, the Trump, administration sought a Chinese scapegoat to distract from the president’s failure to comprehend the emergency his government was facing. Wade complains that “The political agendas of governments and scientists” had generated “thick clouds of obfuscation that the mainstream media seem helpless to dispel.”

What he fails to recognize is the degree to which the obfuscation may have been deliberate, foam on the runway, designed to prevent an apocalyptic political explosion until vaccines were developed and the contagion contained. In the process, a few whoppers about the likelihood that the virus had evolved by itself in nature were devised by members of the world’s virology establishment. Wade’s generosity in his acknowledgments at the end of his article make it clear there was ample reason to want to know more about the lab-leak explanation long before Biden commissioned a review.

Wade is a journalist of a very high order, but to me he seems tone-deaf to the overtones of his assertions. I was reminded of a conversation that Emerson recorded in his journal in 1841. “I told [William Lloyd] Garrison that I thought he must be a very young man, or his time hang very heavy on his hands, who can afford to think much, and talk much, about the foible of his neighbors, or ‘denounce’ and ‘play the son of thunder,’ as he called it.” Wade, in contrast, likes to quote Francis Bacon: “Truth is the daughter, not of authority, but time.”

But remember too that time, as the saying goes, is God’s way of keeping everything from happening at once. The news Friday that The New York Times has been recognized with the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for its coverage of the pandemic was not surprising. There are six months of developments yet to go in 2021, but my hunch is that, when preparations begin for the award next year, a leading nominee will be the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

Arthur Allen: Theory that COVID-19 leaked from Wuhan lab picks up more backers

“Would we throw out the red carpet, ‘Come on over to Fort Detrick and the Rocky Mountain Lab?’ We’d have done exactly what the Chinese did, which is say, ‘Screw you!’”

— Dr. Gerald Keusch, associate director of the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory Institute at Boston University

Once dismissed as a conspiracy theory, the idea that the COVID-19 virus escaped from a Chinese lab is gaining high-profile attention. As it does, reputations of renowned scientists are at risk — and so is their personal safety.

At the center of the storm is Peter Daszak, whose EcoHealth Alliance has worked directly with Chinese coronavirus scientists for years. The scientist has been pilloried by Republicans and lost National Institutes of Health funding for his work. He gets floods of threats, including hate mail with suspicious powders. In a rare interview, he conceded that he can’t disprove that the deadly COVID-19 virus resulted from a lab leak at the Wuhan Institute of Virology — though he doesn’t believe it.

“It’s a good conspiracy theory,” Daszak told KHN. “Foreigners designing a virus in a mysterious lab, a nefarious activity, and then the cloak of secrecy around China.”

But to attack scientists “is not only shooting the messenger,” he said. “It’s shooting the people with the conduit to where the next pandemic could happen.”

Yet what if the messengers were not only bearing bad news but also accidentally unleashed a virus that went on to kill more than 3 million people?

The generally accepted scientific hypothesis holds that the COVID virus arose through natural mutations as it spread from bats to humans, possibly at one of China’s numerous “wet markets,” where caged animals are sold and slaughtered. An alternative explanation is that the virus somehow leaked from the Wuhan Institute, one of Daszak’s scientific partners, possibly by way of an infected lab worker.

The lab-leak hypothesis has picked up more adherents as time passes and scientists fail to detect a bat or other animal infected with a virus that has COVID’s signature genetics. By contrast, within a few months of the start of the 2003 SARS pandemic, scientists found the culprit coronavirus in animals sold in Chinese markets. But samples from 80,000 animals to date have failed to turn up a virus pointing to the origins of SARS-CoV-2 — the virus that causes COVID. The virus’s ancestors originated in bats in southern China, 600 miles from Wuhan. But COVID contains unusual mutations or sequences that made it ideal for infecting people, an issue explored in depth by journalist Nicholas Wade.

Scientists from the Wuhan Institute have collected thousands of coronavirus specimens from bats and registered them in databases closed to inspection. Could one of those viruses have escaped, perhaps after a “gain of function” experiment that rendered it more dangerous?

Daszak, who finds such theories specious, was the only American on a 10-member team that the World Health Organization sent to China this winter to investigate the origins of the virus. The group concluded its work without gaining access to databases at the Wuhan Institute, but dismissed the lab leak hypothesis as unlikely. WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, however, said the hypothesis “requires further investigation.”

On Friday, 18 virus and immunology experts published a letter in the journal Science demanding a deeper dive. “Theories of accidental release from a lab and zoonotic spillover both remain viable,” they said, adding that the Wuhan Institute should open its records. One of the signatories was a North Carolina virologist who has worked directly with the Wuhan Institute’s top scientists.

That demand is “definitely not acceptable,” responded Shi Zhengli, who directs the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases at the Wuhan Institute. “Who can provide evidence that does not exist?” she told MIT Technology Review. Shi has said that thousands of attempts to hack its computer systems forced the institute to close its database.

Many leading virologists continue to believe that “zoonotic transmission” — from a bat or some other animal to a human — remains the most likely origin story. Yet the lack of evidence for that is troubling, 17 months after the emergence of COVID said Stanley Perlman, a University of Iowa virologist who was not among the Science letter signatories.

The fact that no bat or other animal has been found infected with anything resembling the COVID virus, which suddenly swept through Wuhan at the end of 2019, “has put the lab leak hypothesis back on the table,” although there is no evidence supporting that theory either, he said.

Alina Chan, a Broad Institute (based in Cambridge, Mass.) postdoctoral researcher who signed the Science letter, agrees that there is no “dispositive” evidence either way for COVID’s emergence. But a network of amateur sleuths have put together evidence, she said, that the Wuhan Institute has COVID-like viruses in its collection that it has not deposited in global databases, as would be customary during a global pandemic. Chan and others are particularly curious about a bunch of SARS-like viruses that the institute collected from a cave in Yunnan province where guano miners suffered a deadly outbreak of respiratory disease in 2012.

“We don’t have access to that data,” Chan said. She and other scientists wonder why the COVID virus was so ideally suited to human-to-human transmission from the onset without signs of an intermediate host or circulation in the human population before the Wuhan outbreak.

In a paper posted to a virology forum last week, Robert Garry, of Tulane University, who doubts the lab-leak hypothesis, brought forth a new fragment of “spillover” evidence: The WHO report shows that some of the first 168 cases of COVID were linked to two or more animal markets in Wuhan, he said, with strains from different markets showing slight differences in their genetic sequence. “Maybe one animal was in a truck with a bunch of cages and then it spread it to another species and that’s where the shift took place,” Garry said.

Garry and other international scientists have worked with Shi and her lab for years. The evidence for Garry’s supposition isn’t airtight, he admitted, but it’s more convincing than “contriving something where some of the world’s leading virologists are covering up at the behest of the Chinese Communist Party,” he said.

Shi has no greater defender in the United States than Daszak, whose EcoHealth Alliance was a wildlife- protection organization when he joined it two decades ago. The group has since expanded its goals from protecting endangered animals to protecting humans endangered by the pathogens trafficked with those animals. The more than $50 million EcoHealth Alliance had received in U.S. funding since 2007 includes contracts and grants from two NIH institutes, the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Agency for International Development, as well as Pentagon funds to look for organisms that could be fashioned into bioterror weapons.

Daszak has co-authored at least 21 research papers on bat coronaviruses since 2005, finding hundreds of viruses capable of infecting people. He estimated that about 1 million people a year are infected with bat viruses — a number that’s grown as humans encroach on bat habitats.

He recalled a 2019 visit to a cave filled with millions of bats. “Tourists were going in there in shorts, and we were in there in full PPE. They asked us, ‘What are you doing?’ and we told them, ‘We’re looking for viruses like SARS.’’’

In April 2020, citing what he said was evidence of the virus’s link to the Wuhan lab, former President Trump ordered the NIH to cancel a five-year, $3.7 million grant for EcoHealth Alliance’s bat-virus research. But about 70 percent of the group’s annual $12 million budget continues to come from the U.S. government, Daszak said.

When the NIH grant was frozen, Daszak called the lab leak hypothesis “pure baloney,” saying he was confident his Chinese scientific partners were not hiding anything. But he admits it is impossible to disprove.

“There are plenty of reasons to question China’s openness and transparency on a whole range of issues including early reporting of the pandemic,” he told KHN. “You can never definitively say that what China is telling us is correct.”

Daszak said he thinks it more likely that China is covering up the role of the country’s wildlife markets in COVID’s origin. Farming of these animals employs 14 million people, and the government has closed and reopened the markets since SARS. Following the COVID outbreak, the Chinese authorities’ investigation of Wuhan’s animal markets, where the virus could have mutated after passage through different species, was incomplete, Daszak said.

“People don’t realize how sensitive China is about this,” he said. “It’s plausible that they recognized there were cases coming out of a market and they shut it down.”

A Controversy With Roots

The scientific conflict over the lab hypothesis is partly rooted in a debate over “gain-of-function’’ experiments, work that in theory could lead to the creation and release of more infectious or deadly organisms. In such experiments, scientists in a lab can, for example, test a virus’s ability to mutate by exposing it to different cell types or to mice genetically engineered with human immune system traits.

At least six of the 18 signatories of the Science letter are part of the Cambridge Working Group, whose members worry about the release of pathogens from the growing number of virus labs around the world.

In 2012, Dr. Anthony Fauci, who leads NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, came out in support of a moratorium on such research, posing a hypothetical scenario involving a poorly trained scientist in a poorly regulated lab: “In an unlikely but conceivable turn of events, what if that scientist becomes infected with the virus, which leads to an outbreak and ultimately triggers a pandemic?” Fauci wrote.

In 2017, the federal government lifted its pause on such experiments but has since required some be approved by a federal board.

In his questioning of Fauci in the Senate last week, Sen. Rand Paul (R.-Ky.) cited a 2015 paper written by Shi, Ralph Baric, of the University of North Carolina, and others in which they fused a SARS-like virus with a novel bat-virus spike protein and found that it sickened research mice. The experiment provided evidence of the perils that lurked in Chinese bat caves, but the authors also raised the question of whether such studies were “too risky to pursue.”

Critics have jumped on this paper as evidence that Shi was conducting “gain of function” experiments that could have created a superbug, but Shi denies it. The research cited in the paper was conducted in North Carolina.

Using a similar technique, in 2017, Baric’s lab showed that remdesivir — currently the only licensed drug for treating COVID — could be useful in fighting coronavirus infections. Baric also helped test the Moderna covid vaccine and a leading new drug candidate against covid.

Research into COVID-like viruses is vital, Baric said. “A terrible truth,” he said, “is that millions of coronaviruses exist in animal reservoirs, like bats, and unfortunately many appear poised for rapid transmission between species.”

Baric told KHN he does not believe that COVID resulted from gain-of-function research. But he signed the Science letter calling for a more thorough investigation of his Chinese colleagues’ laboratory, he said in an email, because while he “personally believe[s] in the natural origin hypothesis,” WHO should arrange for a rigorous, open investigation. It should review the biosafety level under which bat coronavirus research was conducted at the Wuhan Institute, obtaining detailed information on the training and safety procedures and efforts to monitor possible infections among lab personnel.

Fauci also told KHN, in an email, that “we at the NIH are very much in favor of a thorough investigation as to the origins of SARS-CoV-2.”

Scaling the Wall of Secrecy

U.S.-China tensions will make it very difficult to conclude any such study, scientists on both sides of the issue suggest. With their anti-China rhetoric, Trump and his aides “could not have made it more difficult to get cooperation,” said Dr. Gerald Keusch, associate director of the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory Institute at Boston University. If a disease had emerged from the U.S. and the Chinese blamed the Pentagon and demanded access to the data, “what would we say?” Keusch asked. “Would we throw out the red carpet, ‘Come on over to Fort Detrick and the Rocky Mountain Lab?’ We’d have done exactly what the Chinese did, which is say, ‘Screw you!’”

Still, while China has shut off its laboratories to outside inquiry, that doesn’t mean all investigative avenues are closed, Chan said. Many Chinese scientists were in contact with colleagues and journals outside the country as the pandemic emerged. Those communications may contain clues, Chan said, and someone should methodically interview the contacted individuals.

It’s worth recalling that the only U.S. bioterror attack so far in the 21st Century consisted of a U.S. bioterrorism researcher mailing anthrax spores to politicians and journalists. Hundreds of millions of dollars go into researching organisms around the world and there are risks of leaks, accidental or intentional, no matter how sophisticated the lab, Chan said.

But it would be unwise to limit support for global virus research, said Jonna Mazet, a University of California-Davis professor who led a USAID-funded program that trained scientists around the world to collect and research animal viruses. For her pains, she has received death threats and hacking attacks on her computers and home alarm system.

“If we don’t do the work,” she said, “we’re just sitting ducks for the next one.”

Arthur Allen is a Kaiser Health News journalist.

KHN correspondent Rachana Pradhan contributed to this report.

Phil Galewitz: Vermont giving priority to minorities for COVID vaccinations

Starting April 1, Vermont has explicitly been giving Black adults and people from other minority communities priority status for vaccinations. Although other states have made efforts to get vaccine to people of color, Vermont is the first to offer them priority status, said Jen Kates, director of global health and HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

All Black, Indigenous residents and other people of color who are permanent Vermont residents and 16 or older are eligible for the vaccine.

It will be a short-term advantage, since Vermont opens COVID-19 inoculations to all adults April 19.

Still, Vermont health officials say they hope that the change will lower the risk for people of color, who are nearly twice as likely as whites to end up in the hospital with COVID-19. “It is unacceptable that this disparity remains for this population,” Dr. Mark Levine, M.D.,

Vermont’s health commissioner, said at a recent news conference.

But providing priority may not be enough to get more minority residents vaccinated — and could send the wrong message, some health experts say.

“Giving people of color priority eligibility may assuage liberal guilt, but it doesn’t address the real barriers to vaccination,” said Dr. Céline Gounder, an infectious-diseases specialist at NYU Langone Health and a former member of President Biden’s COVID advisory board. “The reason for lower vaccination coverage in communities of color isn’t just because of where they are ‘in line’ for the vaccine. It’s also very much a question of access.”

Vaccination sites need to be more convenient to where these targeted populations live and work, and more education efforts are necessary so people know the shots are free and safe, she said.

“Explicitly giving people of color priority for vaccination could backfire,” Gounder said. “It could give some the impression that the vaccine is being rolled out to them first as a test. It could reinforce the fear that people of color are being used as guinea pigs for something new.”

Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, said that’s why he has opposed using race as a risk factor to determine covid vaccine eligibility.

But he sees signs that vaccine hesitancy is declining nationally and called Vermont’s new approach “admirable.” Still, he said, states should continue to use a range of options to get vaccines to minority communities, such as providing vaccination sites in Black neighborhoods and places that residents trust, like churches.

No state is achieving equity in its vaccine distribution, said KFF’s Kates.

“People of color, whether they be Black or brown, are being vaccinated at lower rates compared to their representation among covid cases and deaths, and often their population overall,” she said.

Blacks make up about 2 percent of Vermont’s population and 4 percent of its COVID infections, but they have received 1 percent of the state’s vaccines, according to KFF.

“Since states are really not doing well on equity, other strategies are welcome at this point,” said Kates.

Yet, there’s another reason public health officials have balked at explicitly giving people of color vaccine priority. “It could be politically sensitive,” she said.

Phil Galewitz is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Phil Galewitz: pgalewitz@kff.org, @philgalewitz

In Greater Boston, the intersection of the pandemic and immigration

Cambridge Hospital, part of the Cambridge Health Alliance

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

CAMBRIDGE, Mass.

A year into the global pandemic, we are grappling with the scale of its impact and the conditions that created, permitted and exacerbated it. For those of us in the mental health field, tentative strides toward telepsychiatry pivoted to a sudden semi-permanent virtual health-care delivery system. Questions of efficacy, equity and risk management have been raised, particularly for underserved and immigrant populations. The structures of our work and its pillars (physical proximity, co-regulation, confidentiality, in-person crisis assessment) have shifted, leading to other unexpected proximities and perhaps intimacies—seeing into patients’ homes, seeing how they interact with their children, speaking with patients with their abusive partners in the room, listening to the conversation, and patients seeing into our lives.

As the pandemic crisis morphs, it is unclear if we are at the point to do meaningful reflective work, but for now, I offer some thoughts through the lens of my work at Cambridge Health Alliance (CHA), an academic health-care system serving about 140,000 patients in the Boston Metro North region.

CHA is a unique system: a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School, which operates the Cambridge Public Health Department and articulates as “core to the mission,” health equity and social justice to underserved, medically indigent populations with a special focus on underserved people in our communities. Within the hospital’s Department of Psychiatry, four linguistic minority mental-health teams serve Haitian, Latinx, Portuguese-speaking (including Portugal, Cape Verde and Brazil) and Asian patients.

While we endeavour to gather data on this across CHA, anecdotal evidence from the minority linguistic teams supports the existing research suggesting that immigrant and communities of color are bearing a disappropriate impact of COVID-19 in multiple intersecting and devastating ways: higher burden of disease and mortality rates, poorer care and access to care, overrepresentation in poorly reimbursed and “front-facing” vulnerable jobs such as cleaning services in hospitals and assisted care facilities, personal care attendants and home health aides, and overrepresentation in industries that have been hardest hit by the pandemic such as food service, thereby facing catastrophic loss of income.

These patients also face crowded multigenerational living conditions and unregulated and crowded work conditions. These “collapsing effects” are further exacerbated by reports from our patients that they are also being targeted by hateful rhetoric such as “the China virus” and larger anti-immigrant sentiment stoked by the Trump administration and the accompanying narrative of “economic anxiety” that has masked the racialized targeting of immigrants at their workplaces and beyond.

Telehealth. As we provide services, we have also observed that, despite privacy concerns, access to and use of our care has expanded due to the flexibility of telehealth. Patients tell us that they no longer have to take the day off from work to come to a therapy appointment and have found care more accessible and understanding of the demands of their material lives.

Some immigrant patients report that since they use phone and video applications to stay in touch with family members, using these tools for psychiatric care feels normative and familiar. For deeply traumatized individuals, despite the loss of face-to-face contact, the fact that they do not have to encounter the stresses inherent in being in contact with others out in the world has made it more possible for them to consistently engage in care with reduced fear as relates to their anxiety and/or PTSD. These are interesting observations as we try to tailor care and understand “what works for whom.”

Immigrant service providers. Another theme in the dynamics of care during the pandemic is found in the experiences of immigrant service providers whose work has been stretched in previously unrecognizable ways—and remains often invisible.

Prior to the pandemic, for example, CHA had established the Volunteer Health Advisors program, which trains respected community health workers, often individuals who were healthcare providers in their home country, who have a close understanding of the community they serve. They participate in community events such as health fairs to facilitate health education and access to services and can serve as a trusted link to health and social services and underserved communities.

What we have seen during the pandemic is even greater strain on immigrant and refugee services providers who are often the front line of contact. We have provided various “care for the caregiver” workshops that address secondary or vicarious trauma to such groups such as medical interpreters often in the position of giving grave or devastating news to families about COVID-19-related deaths as well as school liaisons and school personnel, working with children who may have lost multiple family members to the virus, often the primary breadwinners, leaving them in economic peril.

While such supportive efforts are not negligible, a public system like ours is vulnerable to operating within crisis-driven discourse and decision making. With the pandemic exacerbating inequities, organizational scholars have noted in various contexts that a state of crisis can become institutionalized. This can foreclose efforts at equity that includes both patient care as well as care for those providing it. The challenge going forward will involve keeping these issues at the forefront of decisions regarding catalyzing technology and the resulting demands on our workforce.

Diya Kallivayalil , Ph.D., is the director of training at the Victims of Violence Program at the Cambridge Health Alliance and a faculty member in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

Keep your virus off our island!

On Matinicus, 20 miles off Maine’s mainland

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The reaction of residents of islands off the New England coast, from big ones, such as Nantucket, to tiny Matinicus, off Maine, to the pandemic has, in a way, been paradoxical. These folks (more than a few of whom tend to be recluses) sometimes feel safer because they are separated by water from the worst COVID case densities, on the mainland, while fearful that a few cases will make their way onto their islands and explode.

There have been some ugly scenes, such as locals stretching chains across driveways of summer people “From Away’’ trying to shelter in place from COVID there and nasty notes.

xxx

Of course, New England’s islands are a big lure in the summer. I wonder how the vaccination surge will affect how many tourists and vacation-home residents visit them this summer as they play travel catch-up.

John O. Harney: New England and other experts address racial and economic reckoning'

Logo of the Color of Change reform group

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Even in this time when people presume to be having a “racial reckoning,” signs of enduring racial inequity pop up everywhere. From nagging disparities in health—Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) die at higher rates than other groups from COVID-19 and are underrepresented in medical research (except in vile experiments such as in the Tuskegee study) … to the steep declines in Black and Latino students submitting the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) … to Black food-service workers experiencing disproportionate short-tipping for enforcing social-distancing rules … inequality reigns. These persistent forces should be a big deal for New England’s Historically White Colleges and Universities, which are rarely called out as HWCUs.

Some help is on the way. Beside targeting $128.6 billion for the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, $39.6 billion to the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund, $39 billion for child care and $1 billion for Head Start, the new $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief plan does other less visible things to begin to address structural racism. For example, the package provides Black farmers with debt relief and help acquiring land. Black farmers lost more than 12 million acres of farmland over the past century, attributed to systemic racism and inequitable access to markets.

I’ve been trying to monitor the racial-equity conversation mostly via Zoom since the pandemic began. This mention of aid to Black farmers reminded me of something I heard Chuck Collins say at a webinar convened last month by MIT’s Sloan School of Management via Zoom titled “The Inclusive Innovation Economy: Amplifying Our Voices Through Public Policy’’.

Collins is the director of inequality and the common good at the Institute for Policy Studies and a white man. He told of his uncle getting a 1 percent fixed-rate mortgage in 1949 to buy an Ohio farm—a public investment that led his cousins to get on “America’s wealth-building train.” Black and Brown people did not get the same benefits. Collins suggested that systems such as CARES relief should be examined with a racial-equity lens, as should policies such as raising the minimum wage or forgiving student loans. Unquestionably, Black students struggle more than whites with student debt. But with Capitol Hill debating the right amount of debt to forgive, Collins suggested we need to test how well these changes would affect racial inequity.

Dynastic wealth

Noting that we’re living through an updraft of “dynastic wealth,” Collins asked why the U.S. taxes work income higher than income from investments. He pointed out that “50 families in the U.S. that are now in their third generation of billionaires coming online and that represents a sort of Democracy-distorting and market-distorting concentration of wealth and power.”

That distortion could be partly cushioned with a “dignity floor,” said Collins. “It’s not a coincidence that a society like Denmark has much higher rates of entrepreneurship than the U.S. per capita because they have a social-safety net and because they have social investments that create a decency floor through which people cannot all. So if you want to start a business, you know you can take that leap and not end up living in your car.”

We need to disrupt the narrative of “everyone is where they deserve to be,” said Collins. So many entrepreneurs tell their story from the standpoint of I did this. We need to talk about the web of supports and multigenerational advantages behind their ability to take the step they took.

Color-coded

An audience member asked if a bridge could be built to connect the rich and poor. To this, one of the conversation moderators, Sloan School lecturer and former chief experience and culture officer at Berkshire Bank Malia Lazu, quipped that in the U.S., there’s another dimension: The sides of the bridge are “color-coded.”