Sam Pizzigati: No, 'the market' doesn't set astronomical CEO pay

Via OtherWords.org

Back in 1999, no executive personified the soaring pay packages of America’s CEOs more than Jack Welch at General Electric. Welch took home $75 million that year.

Welch credited that exorbitant salary not to his own genius, but to the genius of the free market.

“Is my salary too high?” mused Welch. “Somebody else will have to decide that, but this is a competitive marketplace.”

Translation: “I deserve every penny. The market says so.”

Top executives today are doing even better. In 1999, the Economic Policy Institute reports, CEOs at the nation’s 350 biggest corporations pocketed 248 times the pay of average workers in their industries. Top execs last year averaged 312 times more.

Why? Like Welch a generation ago, today’s CEOs point to the market.

As the University of Chicago’s Steven Kaplan puts it, “The market for talent puts pressure on boards to reward their top people at competitive pay levels in order to both attract and retain them.”

In the world of CEO cheerleaders like Kaplan, corporate boards simply pay their execs what the impartial, unbiased market — supply and demand — says they deserve. If they don’t, they risk losing talent.

But do corporations really face a shortage of qualified CEOs?

In fact, Corporate America has never had more talent to choose from to run their multibillion-dollar companies. America’s graduate schools of business have been graduating, year after year, thousands of rigorously trained executives.

The Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth boasts an alumni network over 10,000 strong. MBAs in the equally prestigious Harvard Business School alumni network total over 46,000. Several hundred thousand more execs have been trained at America’s other top-notch business schools.

Let’s assume, conservatively, that only 1 percent of the alumni from the “best” business schools have enough skills and experience to run a big-time corporation. Even that would give Fortune 500 companies looking for a new CEO several thousand qualified candidates.

That’s not even counting the grads from business schools abroad. INSEAD, perhaps the most prominent of these international schools, now has over 56,000 active alumni. In our celebrated “globalized” economy, executives from elsewhere in the world constitute a huge new pool of talent for American corporations.

By classic market logic, any competition between highly paid American executives and equally qualified but more modestly paid international executives ought to end up lowering, not raising, the higher pay rates in the United States. Yet American executives take home over triple the pay of execs in America’s peer nations.

In short, we have a situation that the “market” doesn’t explain. In the executive talent marketplace, American corporations face plenty, not scarcity — yet the going rate for American executives keeps rising.

Simply put, markets don’t set executive pay.

“CEOs who cheerlead for market forces wouldn’t think of having them actually applied to their own pay packages,” as commentator Matthew Miller has noted in the Los Angeles Times. “The reality is that CEO pay is set through a clubby, rigged system in which CEOs, their buddies on board compensation committees, and a small cadre of lawyers and ‘compensation consultants’ are in cahoots to keep the millions coming.”

If CEOs earned less, the Economic Policy Institute study concludes, we would see “no adverse impact on output or employment.” Instead, we’d see higher rewards for workers, since the huge paydays that go to CEOs today reflect “income that otherwise would have accrued to others.”

Back in 1965, the study notes, America’s top execs only pulled down 20 times more pay than the nation’s average workers, as opposed to over 300 times today. If we want an economy where all of us can thrive, not just CEOs, we’d do well to drive that number back down.

Sam Pizzigati co-edits Inequality.org for the Institute for Policy Studies, where a longer version of this piece first appeared. His latest book is The Case for a Maximum Wage.

Steven Clifford: How rigged system produces grotesque CEO pay and hurts America

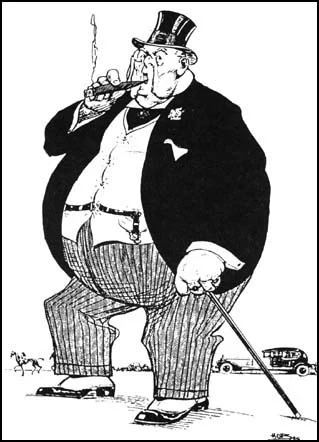

"Avarice'' (2012), by Jesus Solana

Via OtherWords.org

CEO pay at America’s 500 largest companies averaged $13.1 million in 2016. That’s 347 times what the average employee makes.

So CEOs make a lot of money. But, some say, so do athletes and movie stars. Why pick on corporate bosses, then?

First, because the market sets compensation for athletes and movie stars, but not for CEOs. Teams and movie studios bid for athletes and movie stars. CEO pay is set by a rigged system that has nothing to do with supply and demand.

NBA teams bid for LeBron James because his skills are portable: He’d be a superstar on any team. CEOs’ skills are much more closely tied to their knowledge of a single company — its finances, products, personnel, culture, competitors, etc. Such knowledge and skills are best gained working within the company, and not worth much outside.

In fact, a CEO jumping between large companies happens less than once a year. And when they jump, they usually fail.

Lacking a market, CEO pay is set by a series of complex administrative pay practices. Usually a board, often dominated by other sitting or retired CEOs, sets their CEOs pay based on the compensation of other highly paid CEOs. The CEO can then double or triple this target by surpassing negotiated bonus goals.

This amount then increases target pay for his or her peer CEOs, giving another bump. Since 1978 these annual rounds of CEO pay leapfrog have produced a 1,000 percent inflation-adjusted increase in CEO pay.

At the same time, the bottom 90 percent of American workers have seen their real incomes decrease by 3 percent.

American workers were once rewarded for productivity. Inflation-adjusted wages and productivity rose in tandem at about 3 percent annually from 1945 through the mid-'70s. But since then the bosses have taken it all. Although productivity growth increased inflation-adjusted per-capita GDP by 84 percent over the last 36 years, real wages have remained essentially flat.

Where did the money go? It went to the 1 percent, and especially to the 0.1 percent.

The latter group, a mere 124,000 households, pocketed 40 percent of all economic gains. Business executives, CEOs, or others whose compensation is guided by CEO pay constitute two-thirds of this sliver.

In other words, it’s business executives — not movie stars, professional athletes, or heiresses — who grabbed the dollars that once flowed to the American worker.

Outsize CEO compensation harms American companies, and not just in the tens of millions they waste on executive pay. The effects on employee morale are much more costly. When the boss makes 347 times what you do, it’s difficult to swallow his canard that “there’s no I in team.”

Worse, CEO pay encourages a short-term focus. Instead of making productive investments, companies buy back their own stock to keep its price high, which boosts their own paycheck. From 2005 to 2014, stock buybacks by America’s 500 largest public companies totaled $3.7 trillion. This consumed over half of their net income.

That $3.7 trillion could have been invested in plants and equipment, new technology, employee training, and research and development. Instead, corporate America cut R&D by 50 percent, essentially eating the seed corn.

If athletes and movie stars were paid less, team owners and studios would simply make more. The hundreds of millions paid to CEOs, on the other hand, hurts their companies, employees and our economy. It’s a principal driver of our country’s startling income inequality.

One of the few checks on CEO pay is a rule under the Dodd-Frank financial-reform law requiring companies to disclose the ratio of CEO to average worker pay. Congress is now considering repealing this rule.

If you think that CEOs making 347 times what you do shouldn’t be held secret, maybe it’s time to let your representatives know.

Steven Clifford is the former CEO of King Broadcasting and the author of The CEO Pay Machine: How It Trashes America and How to Stop It.

Sam Pizzigati: The insider who blew the whistle on executives' greed

Via OtherWords.org

If you work in a corrupt system, you have two basic options.

First, you could rationalize away your role in the corruption. If you ever left, you tell yourself, they’d just get someone else to do your job. Might as well shut your mouth and collect your paycheck.

But you could also go in an entirely different direction. Graef Crystal certainly did.

Crystal once ranked as one of America’s top enablers of a deeply corrupt — and corrupting — corporate CEO pay system. He could have continued down that path. But he chose to push for change instead. And he kept pushing for years after most people step back.

Crystal just passed away at age 82. We can learn plenty from his remarkable life.

The first lesson: We all have it in us to walk away from corruption.

Crystal had it made back in the 1980s. He had won national renown as an astute and reliable expert on CEO pay. America’s top corporations — such outfits as American Express and General Electric — regularly hired him to consult on their executive pay packages.

Crystal delivered what these major corporations needed: an “expert” rationalization for ever higher levels of executive compensation.

He played this CEO pay game well. Ample rewards came his way. But the game, over time, came to thoroughly disgust him. At the height of his career, Crystal walked away from his corporate gravy train and stopped telling unconscionably overpaid corporate honchos what they wanted to hear.

By the early 1990s, Crystal had a new role: blowing the whistle on executive pay outrages. Crystal brought to the executive pay wars both a firm command of the basic facts — between 1980 and 1990 real CEO pay had doubled — and a wealth of insider anecdotes.

In 1991, Crystal would pen a widely acclaimed book, In Search of Excess: The Overcompensation of American Executives. And over the next quarter-century, he’d take every opportunity to spread the book’s message. He spent years writing nationally syndicated newspaper columns and reached millions through such media outlets as 60 Minutes.

But all of Crystal’s noble efforts in the end fell short. Way short. In the quarter-century after 1990, CEO pay didn’t fall. It soared.

In 1990, as the Economic Policy Institute has detailed, CEO pay at America’s top 350 companies averaged $2.8 million, after adjusting for inflation. In 2014, it was up to $16.3 million.

Meanwhile, over those same years, the pay gap between top CEOs and average workers quadrupled.

And that brings us to a second key lesson from the life and work of Graef Crystal: We simply cannot rely on corporations to clean their own houses.

Crystal worked on the assumption that corporate decision makers, once they understood the games that unworthy CEOs were playing, would bring much better judgment to bear on executive compensation. But that assumption never reflected corporate reality, as we understand quite well on other issues.

We don’t as a society, for instance, trust those who run our corporations to police themselves on corporate behaviors that impact the environment. So why should we trust those who run our corporations to distribute rewards fairly — or keep their own hands out of the till?

We shouldn’t, of course.

That’s why there’s a growing consensus on the need for public action against CEO pay excess. One particularly promising approach: We could start denying government contracts and tax breaks to corporations that pay their executives over 25 or 50 times more than their typical workers are making.

In Graef Crystal’s early adult years, most American corporations could meet that standard. Today most don’t even come close. The current CEO-worker pay gap: 335 times.

Sam Pizzigati, an Institute for Policy Studies associate fellow, co-edits Inequality.org and writes for OtherWords.org. His latest book is The Rich Don’t Always Win.