Christina Jewett: Did misguided mask advice for hospitals drive up COVID-19 death toll?

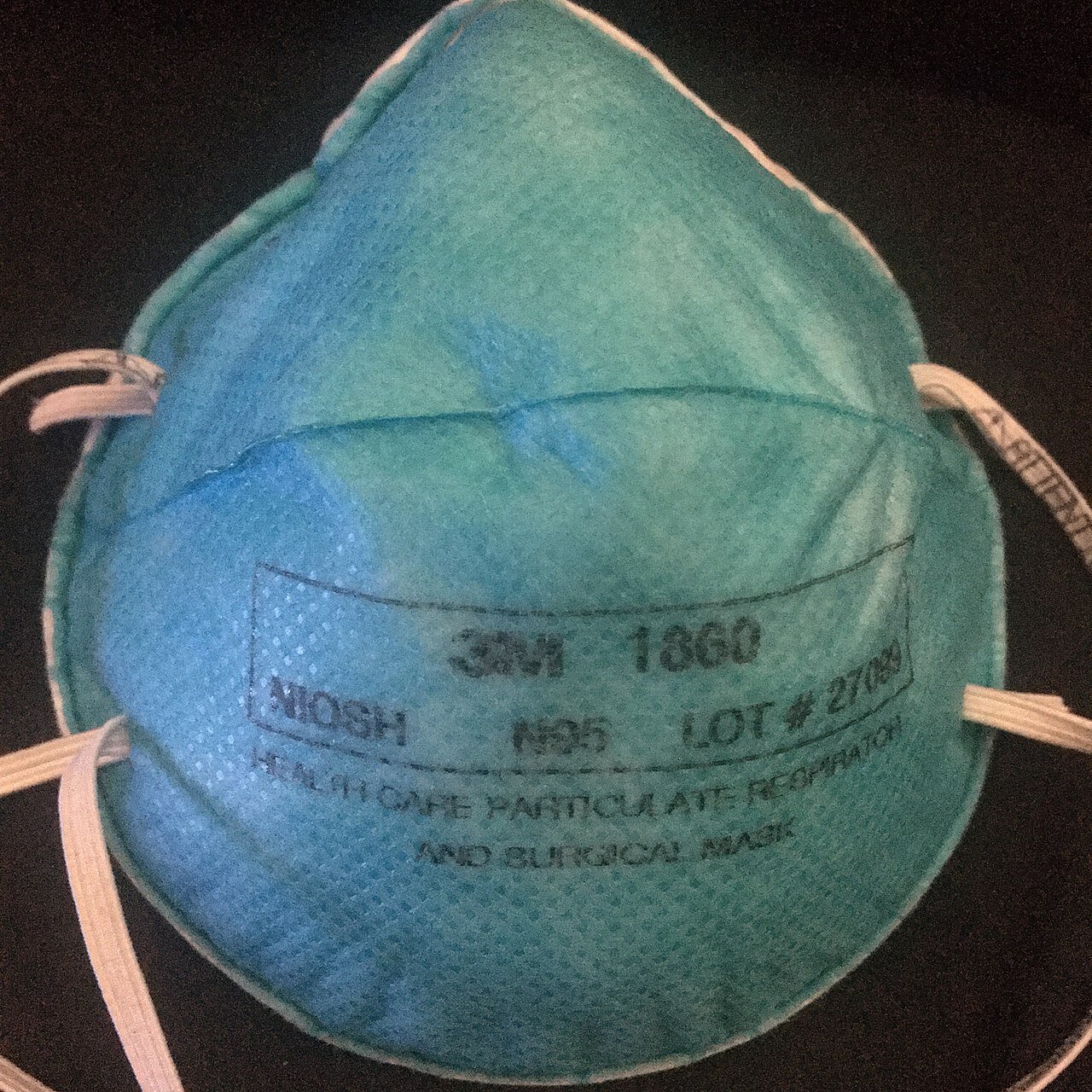

A N95 mask — the safest kind to wear while treating COVID-19 patients

“The whole thing is upside down the way it is currently framed. It’s a huge mistake.’’

— Dr. Michael Klompas, associate professor at the Harvard Medical School, in Boston

Since the start of the pandemic, the most terrifying task in health care was thought to be when a doctor put a breathing tube down the trachea of a critically ill covid patient.

Those performing such “aerosol-generating” procedures, often in an intensive-care unit, got the best protective gear even if there wasn’t enough to go around, per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. And for anyone else working with covid patients, until a month ago, a surgical mask was considered sufficient.

A new wave of research now shows that several of those procedures were not the most hazardous. Recent studies have determined that a basic cough produces about 20 times more particles than intubation, a procedure one doctor likened to the risk of being next to a nuclear reactor.

Other new studies show that patients with COVID simply talking or breathing, even in a well-ventilated room, could make workers sick in the CDC-sanctioned surgical masks. The studies suggest that the highest overall risk of infection was among the front-line workers — many of them workers of color — who spent the most time with patients earlier in their illness and in sub-par protective gear, not those working in the ICU.

“The whole thing is upside down the way it is currently framed,” said Dr. Michael Klompas, a Harvard Medical School associate professor who called aerosol-generating procedures a “misnomer” in a recent paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

“It’s a huge mistake,” he said.

The growing body of studies showing aerosol spread of COVID-19 during choir practice, on a bus, in a restaurant and at gyms have caught the eye of the public and led to widespread interest in better masks and ventilation.

Yet the topic has been highly controversial within the health-care industry. For over a year, international and U.S. nurse union leaders have called for health workers caring for possible or confirmed COVID patients to have the highest level of protection, including N95 masks.

But a widespread group of experts have long insisted that N95s be reserved for those performing aerosol-generating procedures and that it’s safe for front-line workers to care for COVID patients wearing less-protective surgical masks.

Such skepticism about general aerosol exposure within the health-care setting have driven CDC guidelines, supported by national and California hospital associations.

The guidelines still say a worker would not be considered “exposed” to COVID-19 after caring for a sick COVID patient while wearing a surgical mask. Yet in recent months, Klompas and researchers in Israel have documented that workers using a surgical mask and face shield have caught COVID during routine patient care.

The CDC said in an email that N95 “respirators have remained preferred over facemasks when caring for patients or residents with suspected or confirmed” covid, “but unfortunately, respirators have not always been available to health-care personnel due to supply shortages.”

New research by Harvard and Tulane scientists found that people who tend to be super-spreaders of COVID — the 20% of people who emit 80% of the tiny particles — tend to be obese and/or older, a population more likely to live in elder care or be hospitalized.

When highly infectious, such patients emit three times more tiny aerosol particles (about a billion a day) than younger people. A sick super-spreader who is simply breathing can pose as much or more risk to health workers as a coughing patient, said David Edwards, a Harvard faculty associate in bioengineering and an author of the study.

Chad Roy, a co-author who studied other primates with COVID, said the emitted aerosols shrink in size when the monkeys are most contagious at about Day Six of infection. Those particles are more likely to hang in the air longer and are easier to inhale deep into the lungs, said Roy, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Tulane University School of Medicine, in New Orleans.

The study clarifies the grave risks faced by nursing-home workers, of whom more than 546,000 have gotten COVID and 1,590 have died, per reports nursing homes filed to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid since mid-May.

Taken together, the research suggests that health-care workplace exposure was “much bigger” than what the CDC defined when it prioritized protecting those doing “aerosol-generating” procedures, said Dr. Donald Milton, who reviewed the studies but was not involved in any of them.

“The upshot is that it’s inhalation” of tiny airborne particles that leads to infection, said Milton, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Health who studies how respiratory viruses are spread, “which means loose-fitting surgical masks are not sufficient.”

On Feb. 10, the CDC updated its guidance to health-care workers, deleting a suggestion that wearing a surgical mask while caring for covid patients was acceptable and urging workers to wear an N95 or a “well-fitting face mask,” which could include a snug cloth mask over a looser surgical mask.

Yet the update came after most of at least 3,500 U.S. health-care workers had already died of COVID, as documented by KHN and The Guardian in the Lost on the Frontline project.

The project is more comprehensive than any U.S. government tally of health-worker fatalities. Current CDC data shows 1,391 health-care worker deaths, which is 200 fewer than the total staff COVID deaths nursing homes report to Medicare.

More than half of the deceased workers whose occupation was known were nurses or in health-care support roles. Such staffers often have the most extensive patient contact, tending to their IVs and turning them in hospital beds; brushing their hair and sponge-bathing them in nursing homes. Many of them — 2 in 3 — were workers of color.

Two anesthetists in the United Kingdom — doctors who perform intubations in the ICU — saw data showing that non-ICU workers were dying at outsize rates and began to question the notion that “aerosol-generating” procedures were the riskiest.

Dr. Tim Cook, an anesthetist with the Royal United Hospitals Bath, said the guidelines singling out those procedures were based on research from the first SARS outbreak in 2003. That framework includes a widely cited 2012 study that warned that those earlier studies were “very low” quality and said there was a “significant research gap” that needed to be filled.

But the research never took place before COVID-19 emerged, Cook said, and key differences emerged between SARS and COVID-19. In the first SARS outbreak, patients were most contagious at the moment they arrived at a hospital needing intubation. Yet for this pandemic, he said, studies in early summer began to show that peak contagion occurred days earlier.

Cook and his colleagues dove in and discovered in October that the dreaded practice of intubation emitted about 20 times fewer aerosols than a cough, said Dr. Jules Brown, a U.K. anesthetist and another author of the study. Extubation, also considered an “aerosol-generating” procedure, generated slightly more aerosols but only because patients sometimes cough when the tube is removed.

Since then, researchers in Scotland and Australia have validated those findings in a paper pre-published on Feb. 10, showing that two other aerosol-generating procedures were not as hazardous as talking, heavy breathing or coughing.

Brown said initial supply shortages of PPE led to rationing and steered the best respiratory protection to anesthetists and intensivists like himself. Now that it is known emergency room and nursing home workers are also at extreme risk, he said, he can’t understand why the old guidelines largely stand.

“It was all a big house of cards,” he said. “The foundation was shaky and in my mind it’s all fallen down.”

Asked about the research, a CDC spokesperson said via email: “We are encouraged by the publication of new studies aiming to address this issue and better identify which procedures in healthcare settings may be aerosol generating. As studies accumulate and findings are replicated, CDC will update its list of which procedures are considered [aerosol-generating procedures].”

Cook also found that doctors who perform intubations and work in the ICU were at lower risk than those who worked on general medical floors and encountered patients at earlier stages of the disease.

In Israel, doctors at a children’s hospital documented viral spread from the mother of a 3-year-old patient to six staff members, although everyone was masked and distanced. The mother was pre-symptomatic and the authors said in the Jan. 27 study that the case is possible “evidence of airborne transmission.”

Klompas, of Harvard, made a similar finding after he led an in-depth investigation into a September outbreak among patients and staff at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston.

There, a patient who was tested for covid two days in a row — with negative results — wound up developing the virus and infecting numerous staff members and patients. Among them were two patient care technicians who treated the patient while wearing surgical masks and face shields. Klompas and his team used genome sequencing to connect the sick workers and patients to the same outbreak.

CDC guidelines don’t consider caring for a covid patient in a surgical mask to be a source of “exposure,” so the technicians’ cases and others might have been dismissed as not work-related.

The guidelines’ heavy focus on the hazards of “aerosol-generating” procedures has meant that hospital administrators assumed that those in the ICU got sick at work and those working elsewhere were exposed in the community, said Tyler Kissinger, an organizer with the National Union of Healthcare Workers in Northern California.

“What plays out there is there is this disparity in whose exposures get taken seriously,” he said. “A phlebotomist or environmental-services worker or nursing assistant who had patient contact — just wearing a surgical mask and not an N95 — weren’t being treated as having been exposed. They had to keep coming to work.”

Dr. Claire Rezba, an anesthesiologist, has scoured the Web and tweeted out the accounts of health-care workers who’ve died of COVID for nearly a year. Many were workers of color. And fortunately, she said, she’s finding far fewer cases now that many workers have gotten the vaccine.

“I think it’s pretty obvious that we did a very poor job of recommending adequate PPE standards for all health-care workers,” she said. “I think we missed the boat.”

Christina Jewett is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

California Healthline politics correspondent Samantha Young contributed to this report.

Christina Jewett: ChristinaJ@kff.org, @by_cjewett

Victoria Knight: The more opioid marketing, the more overdose deaths

By VICTORIA KNIGHT

Researchers sketched a vivid line on Jan. 18 linking the dollars spent by drugmakers to woo doctors around the country to a vast opioid epidemic that has led to tens of thousands of deaths.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open, looked at county-specific federal data and found that the more opioid-related marketing dollars were spent in a county, the higher the rates of doctors who prescribed those drugs and, ultimately, the more overdose deaths occurred in that county.

For each three additional payments made to physicians per 100,000 people in a county, opioid overdose deaths were up 18 percent, according to the study. The researchers said their findings suggest that “amid a national opioid overdose crisis, reexamining the influence of the pharmaceutical industry may be warranted.”

And the researchers noted that marketing could be subtle or low-key. The most common type: meals provided to doctors.

Dr. Scott Hadland, the study’s lead author and an addiction specialist at Boston Medical Center’s Grayken Center for Addiction, has conducted previous studies connecting opioid marketing and opioid prescribing habits.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to link opioid marketing to a potential increase in prescription opioid overdose deaths, and how this looks different across counties and areas of the country,” said Hadland, who is also a pediatrician.

Nearly 48,000 people died of opioid overdoses in 2017, about 68 percent of the total overdose deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Since 2000, the rate of fatal overdoses involving opioids has increased 200 percent. The study notes that opioid prescribing has declined since 2010, but it is still three times higher than in 1999.

The researchers linked three data sets: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments database that shows drugmakers’ payments to doctors; a database from the CDC that shows opioid prescribing rates; and another CDC set that provides mortality numbers from opioid overdoses.

They found that drugmakers spent nearly $40 million from Aug. 1, 2013, until the end of 2015 on marketing to 67,500 doctors across the country.

Opioid marketing to doctors can take various forms, although the study found that the widespread practice of providing meals for physicians might have the greatest influence. According to Hadland, prior research shows that meals make up nine of the 10 opioid-related marketing payments to doctors in the study.

“When you have one extra meal here or there, it doesn’t seem like a lot,” he said. “But when you apply this to all the doctors in this country, that could add up to more people being prescribed opioids, and ultimately more people dying.”

Dr. Andrew Kolodny, co-director of opioid policy research at Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management, said these meals may happen at conferences or industry-sponsored symposiums.

“There are also doctors who take money to do little small-dinner talks, which are in theory, supposed to educate colleagues about medications over dinner,” said Kolodny, who was not involved in the study. “In reality this means doctors are getting paid to show up at a fancy dinner with their wives or husbands, and it’s a way to incentivize prescribing.”

And those meals may add up.

“Counties where doctors receive more low-value payments is where you see the greatest increases in overdose rates,” said Magdalena Cerdá, a study co-author and director of the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy at the New York University School of Medicine. The amount of the payments “doesn’t seem to matter so much,” she said, “but rather the opioid manufacturer’s frequent interactions with physicians.”

Dr. , who is the co-director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness and was not affiliated with the study, said that the findings about the influence of meals aligns with social science research.

“Studies have found that it may not be the value of the promotional expenditures that matters, but rather that they took place at all,” he said. “Another way to put it, is giving someone a pen and pad of paper may be as effective as paying for dinner at a steakhouse.”

The study says lawmakers should consider limits on drugmakers’ marketing “as part of a robust, evidence-based response to the opioid overdose epidemic.” But they also point out that efforts to put a high-dollar cap on marketing might not be effective since meals are relatively cheap.

In 2018, the New Jersey attorney general implemented a rule limiting contracts and payments between physicians and pharmaceutical companies to $10,000 per year.

The California Senate also passed similar legislation in 2017, but the bill was eventually stripped of the health care language.

The extent to which opioid marketing by pharmaceutical companies fueled the national opioid epidemic is at the center of more than 1,500 civil lawsuitsaround the country. The cases have mostly been brought by local and state governments. U.S. District Judge Dan Polster, who is overseeing hundreds of the cases, has scheduled the first trials for March.

In 2018, Kaiser Health News published a cache of Purdue Pharma’s marketing documents that displayed how the company marketed OxyContin to doctors beginning in 1995. Purdue Pharma announced it would stop marketing OxyContin last February.

Priscilla VanderVeer, a spokeswoman for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, or PhRMA, said that doctors treating patients with opioids need education about benefits and risks. She added that it is “critically important that health care providers have the appropriate training to offer safer and more effective pain management.”

Cerdá said it is also important to consider that the study is not saying doctors change their prescribing practices intentionally.

“Our results suggest that this finding is subtle, and might not be recognizable to doctors that they’re actually changing their behavior,” said Cerdá. “It could be more of a subconscious thing after increased exposure to opioid marketing.”

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

Victoria Knight: vknight@kff.org, @victoriaregisk