David Warsh: From eugenics to molecular biology

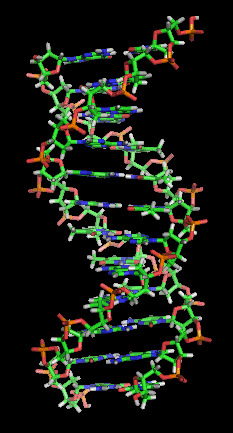

Representation of the now famous “Double Helix’’: Two complementary regions of nucleic acid molecules will bind and form a double helical structure held together by base pairs.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was so long ago that I can no longer remember with any precision the pathways along which the book started me towards economic journalism. What I know with certainty is that The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA (Athenaeum), by James Watson, changed my life when I read it, not long after it was first published, in 1968. Watson’s intimate account of his and Francis Crick’s race with Linus Pauling in 1953 to solve the structure of the molecule at the center of hereditary transmission was thrilling in all its particulars. I went into college one way and came out another, with a durable side-interest in molecular biology.

Thus when Horace Freeland Judson’s The Eighth Day of Creation: Makers of the Revolution in Modern Biology (Simon and Schuster), came along, in 1979, I marveled at Judson’s much more expansive collective portrait of the age. And when Lily Kay’s The Molecular Vision of Life: Caltech, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Rise of the New Biology (Oxford) came out in, in 1993, I was quite taken by the institutional background it supplied.

Kay told the story of how the mathematician Warren Weaver in the 1930s decisively backed the Rockefeller Foundation away from its ill-considered funding backing of the fringes of the eugenics movement – human engineering through controlled breeding – by initiating “a concerted physiochemical attack on [discovering the nature of] the gene… at the moment in history when it became unacceptable to advocate social control based on crude eugenic principles and outmoded racial theories.”

Not until 1938 would Weaver describe his campaign as “molecular biology.” In the dozen years after 1953, Nobel prizes were awarded to 18 scientists for investigation of the nature of the gene, all but one of them funded by the Rockefeller Foundation under Weaver’s direction.

For the past couple of weeks I have been reading Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race (Simon & Schuster, 2021), by Walter Isaacson. Doudna, you may remember (pronounced Dowd-na), shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry last autumn with collaborator Emmanuelle Charpentier “for the development of a method of genetic editing” known as the CRISPR/Cas 9 genetic scissors. The COVID pandemic prevented the journeys to Stockholm that laureates customary make to deliver lectures and accept prizes. Medalists will be recognized at some later date. At that point, expect the significance of the new code-editing technologies to be emphasized. The new know-how recognized in 2020 Prize in Chemistry is probably the most important breakthrough since the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine went to Crick, Watson and Maurice Wilkins, in 1962. Instead of the sterilization and other forceful measures envisaged by the eugenics movement, CRISPR promises to gradually eliminate hereditary disease.

Three themes emerge from Code Breaker. The first is how much has changed with respect to gender, in biological science at least. X-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin died in 1958, four years before she might have shared the prize. (Dead persons are not eligible for the award.) She was cruelly disparaged in Watson’s book, despite the fact that her photographs were crucial to the discovery of the helical structure of the gene.

Opportunities for female scientists had begun to open up by the time that The Eighth Day was published, but women hadn’t yet reached levels of professional accomplishment such that their photographs would appear except rarely in pages dominated by White males. Doudna, born in 1964, and Charpentier, born in 1968, encountered abundant opportunities.

A second theme, less stressed, underscores the extent to which the tables have turned over the last century with respect to the importance attached by scientists to race. Strongly held view about the dispersion of genetic endowments across various populations are nothing new, but, as The New York Times put it a couple of years ago, “It has been more than a decade since James D. Watson, a founder of modern genetics, landed in a kind of professional exile by suggesting that black people are intrinsically less intelligent than whites.”

A third theme, the main story, is Doudna’s decision, as a graduate student in the 1990s, to study the less-celebrated RNA molecule that performs work by copying DNA-coded information in order to build proteins in cells. All this is clearly explained in Isaacson’s book, in relatively short chapters and sub-sections. The effect of this mosaic technique is to briskly move the story along.

After many twists and turns, Doudna and Charpentier showed in June 2012 that “clustered regularly interspersed palindromic repeats” (hence the easy-to-remember-and- pronounce acronym CRISPR), “Cas9” being a particular associated enzyme that did the cutting work, could be made to cut and replace fragments of genes work in a test tube. Within six months, five different papers appeared showing that such scissors would also work in live animal cells.

The famed Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, in Cambridge, where much important biomedical and genomic research is conducted.

An epic patent battle ensued, involving claims to various ways in which CRISPR systems could be used in different sorts of kinds of organisms. A nearly metaphysical argument developed: Once Doudna and Charpentier demonstrated that the technique would work on bacteria, was it “obvious” that it would work in human cells? Rival claimants included Doudna, of the University of California at Berkeley; Charpentier, of Umeå University, Sweden; geneticist George Church, of the Harvard Medical School; and molecular biologist Feng Zhang, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

Church and Zhang are colorful characters with powerful minds and different scientific backgrounds. Their complicated competition with Doudna and Charpentier is said to reprise the race of Watson and Crick with Pauling forty years before. Well-disposed toward all four principals, author Isaacson spends a fair amount of effort interpreting their rival claims. At the end of the book, he expresses the hope that Zhang and Church might one day share a Nobel Prize in Medicine for their CRISPR work.

If there is a better all-around English-language journalist of the last fifty years than Isaacson, I don’t know who that might be. Born in 1952, he grew up in New Orleans, went to Harvard College and then Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar, before beginning newspaper work. He joined Time magazine as a political reporter in 1978; by 1996 he was its editor. To that point he had written two books (the first with Evan Thomas): The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made; (1986); and Kissinger: A Biography (1992).

In 2001 Isaacson left Time to serve as CEO of CNN. Eighteen months later he was named president of the Aspen Institute. There followed, among other books, biographies of Benjamin Franklin (2003), Albert Einstein (2007), Steve Jobs (2011) and Leonardo da Vinci (2017). He resigned from the Aspen Institute in 2017 to become a professor of American History and Values at Tulane University.

As editor of Time, Isaacson took a call in 2000 from Vice President Al Gore, asking on behalf of President Clinton that the visage of National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins be added to that of biotech entrepreneur J. Craig Venter on the cover of a forthcoming issue. A crash program to sequence the human genome was threatening to break apart after the abrasive Venter devised a cheaper means and formed a private company.

Isaacson consulted his sources, including Broad Institute president Eric Lander, a friend from Rhodes Scholar days, and complied. Science journalist Nicholas Wade wrote the story. At least since then, Isaacson has been involved at the highest levels in the story of molecular biology. He is uniquely well-qualified to describe the most recent segment of its arc, and, in the second half of the book, to lay out the many thorny social choices that lie ahead.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran. © 2021 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

Walter Isaacson

John O. Harney: Update on college news in New England

At Wheaton College, which has done very well in facing COVID-19. Left to right: Emerson Hall, Larcom Hall, Park Hall, Mary Lyon Hall, Knapton Hall and Cole Chapel.

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Faculty diversity. In the early 1990s, NEBHE, the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB) and the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) collaborated to develop the first Compact for Faculty Diversity. Formally launched in 1994, with support from the Ford Foundation and Pew Charitable Trust, the compact focused on five key strategies: motivating states and universities to increase financial support for minorities in doctoral programs; increasing institutional support packages to include multiyear fellowships, along with research and teaching assistantships to promote integration into academic departments and doctoral completion; incentivizing academic departments to create supportive environments for minority students through mentorship; sponsoring an annual institute to build support networks and promote teaching ability; and building collaborations for student recruitment to graduate study. With reduced foundation support, collaboration among the three participating regional education compacts declined, but some core compact activities continued through SREB.

Now, NEBHE and its sister regional compacts are launching a collaborative, nine-month planning process to reinvigorate and expand a national Compact for Faculty Diversity. Under the proposed new compact, NEBHE, the Midwestern Higher Education Compact (MHEC), SREB and WICHE would collaborate to invest in the achievement of diversity, equity and inclusion in faculty and staff at postsecondary institutions in all 50 states. Ansley Abraham, the founding director of the SREB State Doctoral Scholars Program at the SREB, has been instrumental in the design and execution of that initiative. He recently published this short piece in Inside Higher Ed.

Fighting COVID. As the head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned of the roughest winter in U.S. public-health history, Wheaton College has stood out. Our Wheaton, in Norton, Mass. (not to be confused with the Wheaton College in Illinois) developed a plan based on science that has kept positive cases low on campus and allowed in-person classes during the fall semester. Wheaton was able to limit the college’s overall fall semester case count to 23 (a .06 positivity rate among 35,000 tests) due to strong protocols, rigorous testing through the Cambridge, Mass.-based Broad Institute and a shared commitment from the community, especially students. In early November, as cases were spiking across the U.S., the private liberal arts college had its own spike of 13 positive cases in one day. But thanks to immediate contact tracing in partnership with the Massachusetts Community Tracing Collaborative, only one positive case resulted after that day, notes President Dennis Hanno. Part of Wheaton’s success owes to its twice-a-week testing throughout the semester. The college also credits its work with the for-profit In-House Physicians to complement internal staff in managing on-campus testing and quarantine/isolation housing.

New England in D.C. The COVID-19 crisis should make national health positions crucial. Earlier this week, President-elect Joe Biden tapped Dr. Rochelle Walensky, an infectious disease physician at Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, to lead the CDC and Dr. Vivek Murthy, who attended Harvard and Yale and did his residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, to be surgeon general. They’ll work with Dr. Anthony Fauci, the chief medical advisor and College of the Holy Cross graduate who has served six presidents.

Last month, as Biden’s transition team began drawing on the nation’s colleges and universities to prepare to take the reins of government, we flashed back to a 2009 NEJHE piece when Barack Obama was stocking his first administration. “As they form their White House brain trusts, new presidents tend to mine two places for talent: their home states and New England—especially New England’s universities, and especially Harvard,” we noted at the time. Most recently, two New England Congresswomen have scored big promotions on Capitol Hill. Rosa DeLauro (D.-Conn.) became Appropriations chair and Katherine Clark (D.-Mass.) was elected assistant speaker of the House. Richard Neal (D.-Mass.) was already chairman of the powerful House Ways and Means Committee.

Indebted. U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D.-Mass.), long a champion of canceling student debt, called on Biden to take executive action to cancel student loan debt. “All on his own, President-elect Biden will have the ability to administratively cancel billions of dollars in student loan debt using the authority that Congress has already given to the secretary of education,” she told a Senate Banking Committee hearing. “This is the single most effective economic stimulus that is available through executive action.” About 43 million Americans have a combined total of $1.5 trillion in federal student loan debt. Such debt has been shown to discourage big purchases, growth of new businesses and rates of home ownership among other life milestones. Warren has outlined a plan in which Biden can cancel up to $50,000 in federal student loan debt for borrowers.

Jobless recovery? Everyone knew the public health crisis would be accompanied by an economic crisis. This week, Moody’s Investors Service projected that the 2021 outlook for the U.S. higher-education sector remains negative, as the coronavirus pandemic continues to threaten enrollment and revenue streams. The sector’s operating revenue will decline by 5 percent to 10 percent over the next year, Moody’s projected. The pace of economic recovery remains uncertain, and some universities have issued or refinanced debt to bolster liquidity. (As this biting piece notes, “Just as decreased state funding has caused students to go into debt to cover tuition and fees, universities have taken on debt to keep their doors open.”)

The name of the game for many higher education institutions (HEIs) is coronavirus relief money from the federal government. NEBHE has written letters to Congress calling for increased relief based on the many New England students and families struggling with reduced incomes or job loss and the costs associated with resuming classes that were significantly higher than anticipated. These costs have been growing based on regular virus testing, contact tracing, health monitoring, quarantining, building reconfigurations, expanded health services, intensified cleaning and the ongoing transition to virtual learning. Citing data from the National Student Clearinghouse, NEBHE estimated that New England’s institutions in all sectors lost tuition and fee revenue of $413 million. And that’s counting only revenue from tuition and fees. Most institutions also face additional budget shortfalls due to lost auxiliary revenues (namely, from room and board) and the high costs of compliance with new health regulations and the administration of COVID-19 tests to students, faculty and staff. (When the relief money is spent and by whom is important too. Tom Brady’s sports performance company snagged a Paycheck Protection Program loan of $960,855 in April.) Anna Brown, an economist at Emsi, told our friends at the Boston Business Journal that higher-ed staffers working in dorms, maintenance roles, housing and food services have been hit hard, and faculty will not be far behind

Admissions blast from the past. I’ve overheard too many conversations lately with reference to “testing” and wondered if the subject was COVID testing or interminable academic exams. Given admissions tests being de-emphasized by colleges, we were reminded me of a 10-year-old piece by Tufts University officials on how novel admissions questions would move applicants to flaunt their creativity. The authors told of how “Admissions officers use Kaleidoscope, as well as the other traditional elements of the application, to rate each applicant on one or more of four scales: wise thinking, analytical thinking, practical thinking and creative thinking.” Could be their moment?

Anti-wokism. The U.S. Department of Education held “What is to be Done? Confronting a Culture of Censorship on Campus” on Dec. 8 (presumably not deliberately on the anniversary of John Lennon’s assassination). The hook was to unveil the department’s “Free Speech Hotline” to take complaints of campus violations. The event organizers contended that “Due to strong demand, the event capacity has been increased!” The department’s Assistant Secretary for Postsecondary Education Robert King began noting that we’ll hear from “victims of cancel culture’s pernicious compact” where generally “administrators cave to the mob and punish the culprit.” He noted, “Coming just behind this are Communist-style re-education camps” and assured the audience that the department has launched several investigations into these kinds of offenses like those that land awkwardly in my inbox from Campus Reform. Universities are no place for “wokism,” one speaker warned, adding that calls for diversity and tolerance actually aim to squelch unpopular opinions.

Welcome dreamers. Last week, a federal judge ordered the Trump administration to restore the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program to how it was before the administration announced plans to end it in September 2017. DACA provides protection against deportation and work authorization to certain undocumented immigrants who were brought to the U.S. as children. DACA participants include many current and former college students. NEBHE issued a statement in support of DACA in September 2017 and has advocated for the initiative’s support.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

David Warsh: In which the whys didn't matter

Jim Simons speaking at the Differential Geometry, Mathematical Physics, Mathematics and Society conference in 2007 in Bures-sur-Yvette, France. He’s a giant of the quants revolution.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The latest book from Gregory Zuckerman is an ideal companion on the reading table next to whatever it is you haven’t read by Michael Lewis, the author who has replaced Tom Wolfe – The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), “The Me Decade and the Third Great Awakening” (1976), Bonfire of the Vanities (1987), A Man in Full (1998) – as the premier storyteller of his age.

Lewis, from Liar’s Poker: Rising through the Wreckage on Wall Street (1989 about Salomon Brothers’ John Gutfreund and financial deregulation) and The New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story (1999, about software entrepreneur Jim Clark and the browser wars that followed the invention of the World Wide Web); to Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game (2003, about new-fangled baseball analytics and Oakland Athletics general manager Billy Bean) to The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game (2006, about new-fangled football analytics and left tackle Michael Oher), has illuminated major changes in familiar institutions, in always entertaining but sometimes misleading ways.

After the 2007-08 financial crisis, Lewis published The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine (2010, about the use of credit default swaps to bet against the subprime mortgage market), followed by Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt (2014, about high-frequency trading).

Zuckerman, who has the advantage of being a special writer for The Wall Street Journal, is the journalist who gets those changes more nearly right, on the stories on which he and Lewis compete.

The Big Short is about Michael Burry, the physician-turned-hedge-fund-operator who recognized the possibilities inherent in the subprime bubble but who failed to get the timing right. Zuckerman’s The Greatest Trade Ever: The Behind-the-Scenes Story of How John Paulson Defied Wall Street and Made Financial History (2009) tells the story of the money manager who made $15 billion for his investors – and $4 billion for himself – by getting the bet down right.

Zuckerman’s new book is The Man Who Solved the Market: How Jim Simons Launched the Quant Revolution (2019). In between he wrote The Frackers: The Outrageous Inside Story of the New Billionaire Wildcatters (2013). When Simons stepped down as head of Renaissance Technologies Corp., in 2009, he was worth more than $11 billion, accumulated in the course of nearly constant trading – a more daunting task, perhaps, than scoring a single brilliant success, as Paulson’s post-2008 experience suggests.

The new book’s title is not quite right. There were plenty of quants before Simons quit the math department at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, many of them making good money. (See The Quants: How a New Breed of Math Whizzes Conquered Wall Street and Nearly Destroyed It (2010), by Scott Patterson, More Money Than God: Hedge Funds and the Making of a New Elite (2011) by Sebastian Mallaby). What set Simons apart was his drive to make the most money from his considerable skills as a professor of mathematics, in collaboration with others possessing an academic degree or skill at the same level.

Nor is the account quite as inside as Zuckerman’s other books. Simons declined to talk to him until fairly late in the game, and then only about certain topics, not including his still-secret recipes. Zuckerman had to work harder for this yarn than he did for the Paulson story, which featured a full-page portrait of its subject opposite the title page.

Simons, a well-adjusted prodigy, grew up in Newton, Mass., and attended Brookline’s Lawrence School. He discovered as an undergraduate at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology that he wasn’t quite at the top level of contemporaries in math, including fellow student Barry Mazur. He was, however, close enough to sail through his math PhD at the University of California at Berkeley in three years, before returning, in 1962, to Cambridge to teach.

Bored, Simons quit after a year to become a code-breaker at the Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA), a Pentagon contractor in Princeton, N.J. In 1968, in collaboration with a Princeton University professor, he published a path-breaking paper in differential geometry that assured his reputation. But Simons had acquired a taste in California for commodity trading, and in his spare-time as a code breaker he and three colleagues published a stock-trading scheme. Zuckerman writes,

Here’s what was really unique. The paper didn’t try to identify or predict [various market] states using economic theory or other conventional methods, nor did the researchers seek to address why the market entered certain states. Simons and his colleagues used mathematics to determine the set of states best fitting the observed pricing data; their model then made its bet accordingly. The whys didn’t matter, Simons and his colleagues seem to suggest, just the strategies to take advantage of the inferred states.

One thing led to another. In 1968, at the age of 30, Simons left IDA for Stony Brook, on the north shore of Long Island, where the university administration had set out to establish a mathematics department strong enough to complement its world-class biology department. In 1976 he was recognized with the Oswald Veblen Prize, the profession’s highest honor in geometry. Two years after that, he quit the university and rented a storefront office in a strip mall across from the Stony Brook railroad station as proprietor of Monemetrics, a currency-trading firm, and Limroy, a tiny hedge-fund. A year later, two other distinguished mathematicians signed on as his partners.

It wasn’t a smooth beginning. Partners came and went. Mergers and acquisitions flourished, and with them the return to inside information – the opposite of the advantage Simons sought. But computer power doubled every two years, according to Moore’s Law, while prices fell by half. Simons changed his firm’s name to Renaissance Technologies.

By 1991 the talk of Wall Street was a former Columbia University computer science professor named David Shaw. He had learned the techniques of statistical arbitrage at Morgan Stanley before the old-line investment bank slashed the funding of one of its most profitable units after it had a bad year. Now, backed by veteran bond trader Donald Sussman, Shaw’s startup was the cutting edge of computer-based trading strategies.

Simons understood that, in order to compete with Shaw, he would need to develop new methods. Financial backers whom he sought, including legendary Commodities Corp., turned him down Among those he hired was mathematician Henry Laufer, a former Stony Brook colleague with a knack for programming. And among those Laufer hired was a British code-breaker named Greg Patterson now working at the IDA.

Patterson possessed a special advantage. As a Brit, trained in the out-of-style methods that enabled British cryptographers to decipher the Germans’ wartime Enigma code, he was aware of new computer-based applications of Bayesian statistics. These were techniques based on the fundamental insight of Rev. Thomas Bayes, an eighteenth-century amateur mathematician that, by periodically updating one’s initial presuppositions with newly arrived objective information, one could continually improve one’s understanding of many matters. For an especially clear account of the history of Bayes’ Theorem, see The Theory That Would Not Die: How Bayes’ Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines, and Emerged Triumphant from Two Centuries of Controversy (2011), by veteran science writer Sharon Bertsch McGrayne

In 1992, the cynosure of the Bayesian community was the little group of computational linguists at IBM Corp. that had run rings around a competing team of linguistics theorists working on machine translation – by the simple expedient of feeding into its powerful computers decades of French-English translations of Canadian parliamentary debates. The computers were armed with machine-learning algorithms that had been instructed to search for patterns. Ever-more dependable translation patterns emerged.

When Patterson learned that IBM was reluctant to permit its team leaders to commercialize their discoveries, he hired Robert Mercer and Peter Brown who had been leaders of the team. Laufer had built a platform that permitted trading across asset classes. It turned out that the methods Mercer and Brown brought with them had wide applicability to the enormous streams of financial data that was becoming ever more plentiful. It was at that point that Renaissance Technologies began to overtake its competitors.

Medallion, the firm’s main fund, earned 71 percent on its capital in 1994, 38 percent in 1995, 31 percent in 1996, and a paltry 21 percent in 1997, a bad year. In 1998, though, D.E. Shaw suffered stinging losses, and Long Term Capital management, Simons’ other main competitor, went bust, after Russia defaulted on its government bonds. By 2000, Medallion returned 99 percent on the $4 billion invested with it, even after Simons collected 20 percent of the gains and five percent of the total invested.

Simons and his colleagues had indeed “solved the market,” at least until their competitors got wise to their methods, but the tumult didn’t go away. Mercer and Brown gradually took over day-to-day management of the firm. A couple of disagreeable Ukrainians traders signed on. The Bayesian Patterson departed for the Broad Institute, in Cambridge, Mass., to work on genomic problems. And in 2016, the libertarian Mercer, by now a billionaire himself, turned out to be, with his daughter Rebekah, a major strategist and funder of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. Simons forced his resignation from the firm. It all makes for fascinating reading.

At one point, Zuckerman jokes that his next book will be about fortunes made in “the golden age of porn.” He is kidding, and a good thing too. The still-bigger fortune out there is BlackRock, the $7 trillion asset-management firm founded by Larry Fink and partners in 1987, the year of a great “market break,” after which a great deal of modern financial technology took hold. With such a book, covering the rise of private equity firms as well, a basic map of the major features of twenty-first century finance would be complete.

David Warsh, an economic historian veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

© 2020 DAVID WARSH, PROPRIETOR

How microbiomes affect disease

Escherichia coli: a long-term resident in our gut

This is from the New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com):

"IBM and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) are joining forces to study how human microbiomes affect various diseases.

"In collaboration with the Broad Institute, the University of California {at} San Diego and the Simons Foundation’s Flatiron Institute, IBM and MGH will attempt to map the three million bacterial genes found in the human microbiome to further understand how to treat diseases such as Type 1 diabetes, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis. Research at this level is unprecedented and a massive amount of computing power is required for analysis which is where IBM’s 'citizen science' World Community Grid enters the picture. The World Community Grid is a hyper-secure software that can gauge when a personal computer has processing power to spare and then remotely run experiments for the project. Anyone with Internet can chose to contribute to the study by joining the Microbiome Immunity Project through IBM’s World Community Grid.

“'This type of research on the human microbiome, on this scale, has not been done before,' said Ramnik Xavier, co-director of the Infectious Disease and Microbiome Program at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and chief of the gastrointestinal unit at MGH. 'It’s only possible with massive computational power.'''