William Morgan: Looking lithographically at proud 19th Century Maine

As part of its celebration of the 200th anniversary of Maine statehood, the Bowdoin College Museum of Art last winter held an exhibition of lithographs of 19th-Century town views in the Pine Tree State. Since then, the college and Brandeis University Press have published a handsome oversize book, Maine's Lithographic Landscapes: Town and City Views, 1830-1870.

What it says above:

“View of Portland, Me./Taken from Cape Elizabeth before the great conflagration of July 4th 1866

“Tinted lithograph from a photograph taken by Edward F. Smith and published by B.B. Russell & Co., Boston. 1866. ‘‘

The author is Maine State Historian Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., who was the state's historic-preservation officer for nearly five decades. The modest and scholarly Shettleworth may well know more about the state's architecture and other art than anyone else. Devoting his life to documenting everything Maine, he has written and lectured prodigiously on every aspect of Maine's built environment, and also written studies of female fly fisherman, photographers, painters, and parks.

“Augusta, Me., 1854.

Drawn by Franklin B. Ladd. Tinted lithograph by F. Heppenheimer, New York.’’

In a bit of Maine understatement, the co-director of the Bowdoin Museum, Frank H. Goodyear Jr., writes, "In Nineteenth Century America, the printed city view enjoyed wide popularity." As Shettleworth notes, the prints helped "forge the young state's identity” and served as "expressions of pride of place’’. During the period under review many towns and cities across America were memorialized in printed images drawn by artists famous and unknown.

Still, Maine was still a small state in the back of beyond. (its population was under 300,000 at the time it separated from Massachusetts, in 1820.) Thus, what the book’s creators call the "first comprehensive record of urban prints during the first fifty years of statehood" is somewhat limited: There are a total of 26 views of 11 places. Those are augmented by a score or more images of the often somber Bowdoin campus, including a painting, old photos, and two Wedgwood plates. Groundbreaking as the book is, viewing the exhibition itself would probably be more satisfying.

That said, Maine's Lithographic Landscapes is a handsome production. The Bowdoin Museum has a history of elegant catalogs, and this co-operative venture with Brandeis demonstrates that press's growing role as a publisher of New England studies. I am not sure that anyone looks at colophons (publisher’s emblems) anymore, so it is worth noting that the book was designed by the eminent book designer, Sara Eisenman.

Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Maine's Lithographic Landscapes, Brandeis University Press, 2020, 144 pages, $50.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian, photographer and essayist. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

The first college book?

Bowdoin College about 1845.

"In an ancient though not very populous settlement, in a retired corner of one of the New England states, arise the walls of a seminary of learning, which, for the convenience of a name, shall be entitled 'Harley College'.''

--From the novel Fanshawe: A Tale, by Nathaniel Hawthorne. It is said to be the first novel about college life. Harley is based on Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine, which Hawthorne attended in 1821-25.

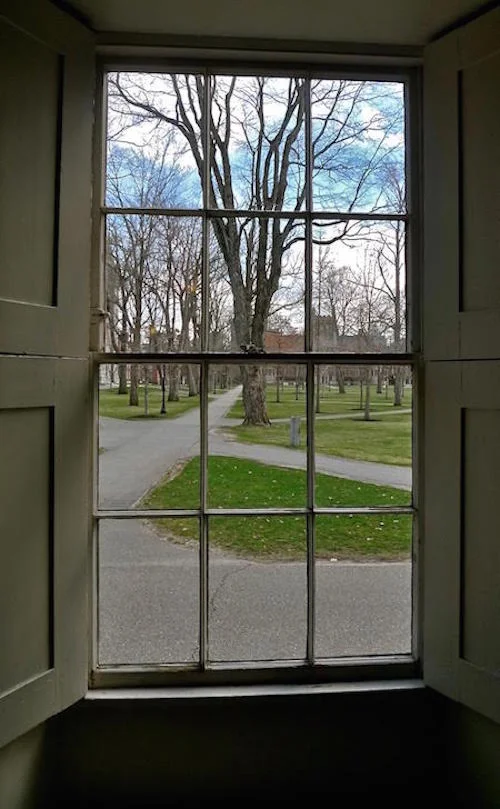

The Main Quad at Bowdoin.

Arctic adventure at Bowdoin

Go while it's still winter. Or go on a hot day in summer to think about cool.

The Peary-McMillan Arctic Museum, at Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine, has lots of neat things (such as an oak-and-rawhide sledge, furry and leathery clothing for surviving Arctic weather and entries from an expedition journal) from the polar expeditions of Robert Peary and Donald MacMillan

Peary claimed to have been the first person to have reached the North Pole, in 1909, although that has been disputed. He was a hell of a promoter. It paid off. See his Eagle Island home in Maine's Casco Bay immediately below.

Most of the Bowdoin campus is lovely, with the Charles McKim-designed college art museum, below, the high point.

Tax your enemies!

View of the Bowdoin College campus, in Brunswick, Maine, from Coles Tower. Bowdoin is one of the rich institutions that would be hit by the GOP endowment tax plan.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

The Trump regime and its allies in Congress are trying to use the powers of the federal government to attack groups that they see as political enemies. There are numerous examples in the House and Senate tax bills, both of which measures are excessively aimed at further expanding the wealth of the very rich and their families and descendants as the current Gilded Age rolls on.Fr

One of particular interest to New Englanders is a plan by congressional Republicans to impose a 1.4 percent tax on the annual income spun off by the endowments of the about 60 schools whose endowments exceed $250,000 per student. This has put pressure on some of our region’s famous private institutions – as The Boston Globe has noted, “including Harvard, Dartmouth and a dozen other New England schools.’’

Now, I have long complained that some of these “not-for-profit’’ schools have long been run in ways that raise eyebrows, especially with the astronomical salaries and perks that they pay too many of their administrators. And one wonders why so much money is spent for luxury frills such as climbing walls, gourmet food and spas.

Still, most of their endowment income is spent to pay for such traditional college functions as teaching, research, financial aid and building maintenance. And many of these institutions have international reputations that draw the brightest students, teachers and researchers, who help strengthen the U.S. economy and wider society, especially through innovation. New England, with its renowned collection of celebrated colleges and universities, has especially benefited from this sector. It bears noting that the bigger the endowment, the more money for scholarships and other forms of financial aid.

The Trump regime and some Republicans in Congress are trying to use the byzantine tax code to weaken institutions associated with the highly educated voters who often oppose the current demagogic version of the Republican Party and who believe in such things as science.

Meanwhile, Harvard Business School Prof. Clayon Christensen predicts: "50 percent of the 4,000 colleges and universities in the U.S. will be bankrupt in 10 to 15 years." Please hit this link to read more: https://www.cnbc.com/2017/11/15/hbs-professor-half-of-us-colleges-will-be-bankrupt-in-10-to-15-years.html?__source=twitter%7Cmain

He’s right. There are too many colleges

William Morgan: Touring the treasures of a cold campus

Spring in northern New England is a sometime thing. It does not usually come until May, if at all, and it doesn’t stay very long. (There's a bit of Yankee humor: "Spring around here is short. Last year, we played baseball that afternoon''.) A recent visit to Maine reminded me that we were still very much in what the late Noel Perrin, my favorite Dartmouth professor, called one of New England's six seasons: "Unlocking''. Except for a few brave daffodils, there were no flowers to be seen and few leaves on the trees.

Waiting for spring: House neat Wiscasset, Maine.

My wife and I walked around Bowdoin College during this period of grayness. Where, we wondered, were the crowds of prospective Polar Bears touring the campus on their spring break? Our own son had seen the Brunswick school in the flush of summer. Would an introduction in November or March have chilled his ardor for Bowdoin? What about students from Virginia or California showing up expecting Maine to look as it appears in online college promotional material?

Main Green at Bowdoin College, looking north.

Yet, we found something strangely appealing about Bowdoin at this time of year–a kind of astringency, a stark honesty defined by barebones trees. There was a sense of what it means to live in Maine year round, or to have attended Bowdoin, say, back in the 1820s, along with Longfellow and Hawthorne, when Brunswick was far away and pretty isolated from the world.

View of the green from Massachusetts Hall (1802),Bowdoin's oldest building.

Minus the leafed-out of shrubbery and flowering trees, it is a lot easier to appreciate the astounding collection of notable 19th Century and early 20th Century architecture that forms the center of the Bowdoin campus.

Charles McKim, of McKim, Mead & White, was the most famous American architect to build at Bowdoin. The Walker Art Museum (1894) is a perfect Renaissance revival jewel. The Western canon of painters, sculptors and architects whose names are carved on the façade might now be seen as a group of dead white men, but it was a typical homage found on Beaux-Arts civic buildings

Richard Upjohn was another giant of American architecture, best known for his Gothic revival churches, such as Trinity Church on Wall Street in New York. Upjohn, however, employed his beloved English Gothic only for Episcopalians. So the Bowdoin Chapel, 1844-55, was built in a severe German Romanesque for the Maine Congregationalists–a commanding if stern house of worship.

The tall and narrow chapel, with its large murals and painted ceiling, is an unexpected change from the starkness of unadorned white interiors of the typical New England meetinghouse.

Although not as famous as either Upjohn or McKim, Boston architect Henry Vaughan was a major designer of churches and colleges. Like Upjohn, he championed English Gothic. Here, Searles Science Hall of 1894 is an early example of a Jacobean-inspired collegiate building in America.

Echoes of Oxford and Cambridge, where Vaughan worked before emigrating to America, inform his Hubbard Library (1903). Soon, the lawn would be home to Frisbee games.

Above the entrance to Hubbard Library is this flowing banner carved with the admonition: Here Seek Converse With The Wise Of All Ages. Would such a motto be welcome in today's politically correct academy?

William Morgan is a longtime architectural historian and essayist. His books include Monadnock Summer: The Architectural Legacy of Dublin, New Hampshire and A Simpler Way of Life: Old Farmhouses of New York and New England

.