Another triumph for New England biotech?

The Philip A. Sharp Building, in Cambridge, which houses the headquarters of Biogen

— Photo by Astrophobe

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’ in GoLocal24.com

This is another “we’ll see’’ situation that gives hope.

Japan’s Eisai Co. and Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen Inc. have developed a drug, called lecanemab, that destroys the amyloid protein plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Patients in the drug trial have had a slowing of symptoms. Researchers have much to learn about the drug’s benefits, side-effects and cost, but the apparent breakthrough may the most hopeful sign yet that a highly effective treatment of this terrible dementia might be in the offing.

Hit this link for The New England Journal of Medicine article on this.

Further, since the buildup of abnormal proteins in the brain is also seen in such (usually) old-age-related ailments as Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease, lecanemab may have wider applications than just for Alzheimer’s as the population continues to age.

This could be another triumph for New England’s bio-tech industry, but it may take many months to find out for sure.

Judith Graham: Patients sharply divided over Alzheimer’s drug

Self-portrait of American figurative artist William Utermohlen, created after he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, in 1995. He experienced memory loss beginning in 1991. After his diagnosis he began creating self-portraits and continued it for another six years, until he made the final self-portraits in 2001. He died in 2007. In the years after the publication of his works in The Lancet in 2001, Utermohlen's self-portraits have been displayed in several exhibitions. His self-portraits inspired the 2019 short film Mémorable.

If you listen to the nation’s largest Alzheimer’s disease advocacy organizations, you might think everyone living with Alzheimer’s wants unfettered access to Aduhelm, a controversial new treatment produced by the Cambridge, Mass., biotech company Biogen.

But you’d be wrong.

Opinions about Aduhelm (also known as aducanumab) in the dementia community are diverse, ranging from “we want the government to cover this drug” to “we’re concerned about this medication and think it should be studied further.”

The Alzheimer’s Association and UsAgainstAlzheimer’s, the most influential advocacy organizations in the field, are in the former camp.

Both are pushing for Medicare to cover Aduhelm’s $28,000 annual per-patient cost and fiercely oppose the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ January proposal to restrict coverage only to people enrolled in clinical trials. Nearly 10,000 comments were received on that proposal, and a final decision is expected in April.

“With respect, we have no more time for debate or delay,” the Alzheimer’s Association national Early-Stage Advisory Group wrote in a Feb. 10 comment. “Every passing day without access to potential treatments subjects us to a future of irreversible decline.” For its part, UsAgainstAlzheimer’s called CMS’ proposal “anti-patient.”

Yet the scientific evidence behind Aduhelm is inconclusive, its efficacy in preventing the progression of Alzheimer’s remains unproved, and there are concerns about its safety. The FDA granted accelerated approval to the medication last June but ordered the drugmaker, Biogen, to conduct a new clinical trial to verify its benefit. And the agency’s decision came despite a 10-0 recommendation against doing so from its scientific advisory committee. (One committee member abstained, citing uncertainty.)

Other organizations representing people living with dementia are more cautious, calling for more research about Aduhelm’s effectiveness and potential side effects. More than 40 percent of people who take the medication have swelling or bleeding in the brain — complications that need to be carefully monitored.

The Dementia Action Alliance, which supports people living with dementia, is among them. In a statement forwarded to me by CEO Karen Love, the organization said, “DAA strongly supports CMS’s decision to limit access to aducanumab to people enrolled in qualifying clinical trials in order to better study aducanumab’s efficacy and adverse effects.”

Meanwhile, Dementia Alliance International — the world’s largest organization run by and for people with dementia, with more than 5,000 members — has not taken a position on Aduhelm. “We felt that coming out with a statement on one side or another would split our organization,” said Diana Blackwelder, its treasurer, who lives in Washington, D.C.

Blackwelder, 60, who was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in 2017, told me, “To say that millions of people afflicted with a disease are all up in arms against CMS’s proposal is just wrong. We’re all individuals, not a collective.”

“I understand the need for hope,” she said, expressing a personal opinion, “but people living with dementia need to be protected as well. This drug has very serious, frequent side effects. My concern is that whatever CMS decides, they at least put in some guardrails so that people taking this drug get proper workups and monitoring.”

The debate over Medicare’s decision on Aduhelm is crucial, since most people with Alzheimer’s are older or seriously disabled and covered by the government health program.

To learn more, I talked to several people living with dementia. Here’s some of what they told me:

Jay Reinstein, 60, is married and lives in Raleigh, N.C. He was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease three years ago and formerly served on the national board of directors of the Alzheimer’s Association.

“I understand [Aduhelm] is controversial, but to me it’s a risk I’m willing to take because there’s nothing else out there,” Reinstein said, noting that people he’s met through support groups have progressed in their disease very quickly. “Even if it’s a 10 percent chance of slowing [Alzheimer’s] down by six months, I am still willing to take it. While I am progressing slowly, I want more time.”

Laurie Scherrer of Albertville, Ala., was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s and frontotemporal dementia in 2013, at age 55.

Early on, she was prescribed Aricept (donepezil), one of a handful of medications that address Alzheimer’s symptoms. “I became totally confused and disoriented, I couldn’t think, I couldn’t concentrate,” she told me. After stopping the medication, those symptoms went away.

“I am not for CMS approving this drug, and I wouldn’t take it,” Scherrer said. At discussion groups on Aduhelm hosted by the Dementia Action Alliance (Scherrer is on the board), only two of 50 participants wanted the drug to be made widely available. The reason, she said: “They don’t think there are enough benefits to counteract the possible harms.”

Rebecca Chopp, 69, of Broomfield, Colo., was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in March 2019. She’s a former chancellor of the University of Denver.

Chopp is a member of a newly formed group of five people with dementia who meet regularly, “support one another,” and want to “tell the story of Alzheimer’s from our perspective,” she said.

Two people in the group have taken Aduhelm, and both report that it has improved their well-being. “I believe in science, and I am very respectful of the large number of scientists who feel that [Aduhelm] should not have been approved,” she told me. “But I’m equally compassionate toward those who are desperate and who feel this [drug] might help them.”

Chopp opposes CMS’s decision because “Aduhelm has been FDA-approved and I think it should be funded for those who choose to take it.”

Joanna Fix, 53, of Colorado Springs was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in October 2016. She, too, developed serious complications after taking Aricept and another dementia medication, Namenda (memantine).

“I would love it if tomorrow somebody said, ‘Here’s something that can cure you,’ but I don’t think we’re at that point with Aduhelm,” Fix told me. “We haven’t been looking at this [drug] long enough. It feels like this is just throwing something at the disease because there’s nothing else to do.”

“Please, please take it from someone living with this disease: There is more to life than taking a magic pill,” Fix continued. “All I care about is my quality of life. My marriage. Educating and helping other people living with dementia. And what I can still do day to day.”

Phil Gutis, 60, of Solebury, Penn., has participated in clinical trials and taken Aduhelm for 5½ years after being diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in 2016.

He’s convinced the medication has helped him. “I don’t know how to describe it other than to say my head feels so much clearer now,” he told me. “I feel much more capable of doing things now. It’s not like I’ve gained my memories back, but I certainly haven’t deteriorated.”

Gutis thinks CMS’s proposed restrictions on Aduhelm are misguided. “When the FDA approved it, there was this sense of excitement — oh, we’re getting somewhere. With the CMS decision, I feel we are setting the field back again. It’s this constant feeling that progress is being made and then — whack.”

Christine Thelker, 62, is a widow who lives alone in Vernon, British Columbia. She was diagnosed with vascular dementia seven years ago and is a board member for Dementia Advocacy Canada, which supports restrictions on Aduhelm’s availability.

“Most of us who live with dementia understand a cure is not likely: There are too many different types of dementia, and it’s just too complicated,” Thelker told me. “To think we’re just going to take a pill and be better is not realistic. Don’t give us false hope.”

What people with Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia need, instead, is “various types of rehabilitation and assistance that can improve our quality of life and help us maintain a sense of hope and purpose,” Thelker said.

Jim Taylor of New York City and Sherman, Conn., is a caregiver for his wife, Geri Taylor, 78, who has moderate Alzheimer’s. She joined a clinical trial for Aduhelm in 2015 and has been on the drug since, with the exception of about 12 months when Biogen temporarily stopped the clinical trial. “In that period, her short-term memory and communications skills noticeably declined,” Jim Taylor said.

“We’re convinced the medication is a good thing, though we know it’s not helpful for everybody,” Taylor continued. “It really boosts [Geri’s] spirits to think she’s part of research and doing everything she can.

“If it’s helpful for some and it can be monitored so that any side effects are caught in a timely way, then I think [Aduhelm] should be available. That decision should be left up to the person with the disease and their care partner.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Biogen headquarters in Cambridge, one of the world’s biotech centers.

Judith Graham: With the arrival of Aduhelm, what is 'mild cognitive impairment'?

19th Century drawing of man with dementia

The approval of a controversial new drug for Alzheimer’s disease, Aduhelm, made by Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen, is shining a spotlight on mild cognitive impairment — problems with memory, attention, language or other cognitive tasks that exceed changes expected with normal aging.

(Kendall Square in Cambridge, Biogen’s neighborhood, has become arguably the bio-tech center of the world.)

After initially indicating that it could be prescribed to anyone with dementia, the Food and Drug Administration now specifies that the prescription drug be given only to individuals with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage Alzheimer’s, the groups in which the medication was studied.

Yet this narrower recommendation raises questions. What does a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment mean? Is Aduhelm appropriate for all people with mild cognitive impairment, or only some? And who should decide which patients qualify for treatment: dementia specialists or primary-care physicians?

Controversy surrounds Aduhelm because its effectiveness hasn’t been proved, its cost is high (an estimated $56,000 a year, not including expenses for imaging and monthly infusions), and its potential side-effects are significant (41 percent of patients in the drug’s clinical trials experienced brain swelling and bleeding).

Furthermore, an FDA advisory committee strongly recommended against Aduhelm’s approval, and Congress is investigating the process leading to the FDA’s decision. Medicare is studying whether it should cover the medication, and the Department of Veterans Affairs has declined to do so under most circumstances.

Clinical trials for Aduhelm excluded people over age 85; those taking blood thinners; those who had experienced a stroke; and those with cardiovascular disease or impaired kidney or liver function, among other conditions. If those criteria were broadly applied, 85 percent of people with mild cognitive impairment would not qualify to take the medication, according to a new research letter in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Given these considerations, carefully selecting patients with mild cognitive impairment who might respond to Aduhelm is “becoming a priority,” said Dr. Kenneth Langa, a professor of medicine, health management and policy at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Ronald Petersen, who directs the Mayo Clinic’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, said, “One of the biggest issues we’re dealing with since Aduhelm’s approval is, ‘Are appropriate patients going to be given this drug?’”

Here’s what people should know about mild cognitive impairment based on a review of research studies and conversations with leading experts:

Basics. Mild cognitive impairment is often referred to as a borderline state between normal cognition and dementia. But this can be misleading. Although a significant number of people with mild cognitive impairment eventually develop dementia — usually Alzheimer’s disease — many do not.

Cognitive symptoms — for instance, difficulties with short-term memory or planning — are often subtle but they persist and represent a decline from previous functioning. Yet a person with the condition may still be working or driving and appear entirely normal. By definition, mild cognitive impairment leaves intact a person’s ability to perform daily activities independently.

According to an American Academy of Neurology review of dozens of stuies, published in 2018, mild cognitive impairment affects nearly 7 percent of people ages 60 to 64, 10 percent of those 70 to 74 and 25 percent of 80-to-84-year-olds.

Causes. Mild cognitive impairment can be caused by biological processes (the accumulation of amyloid beta and tau proteins and changes in the brain’s structure) linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Between 40 percent and 60 percent of people with mild cognitive impairment have evidence of Alzheimer’s-related brain pathology, according to a 2019 review.

But cognitive symptoms can also be caused by other factors, including small strokes; poorly managed conditions, such as diabetes, depression and sleep apnea; responses to medications; thyroid disease; and unrecognized hearing loss. When these issues are treated, normal cognition may be restored or further decline forestalled.

Subtypes. During the past decade, experts have identified four subtypes of mild cognitive impairment. Each subtype appears to carry a different risk of progressing to Alzheimer’s disease, but precise estimates haven’t been established.

People with memory problems and multiple medical issues who are found to have changes in their brain through imaging tests are thought to be at greatest risk. “If biomarker tests converge and show abnormalities in amyloid, tau and neuro-degeneration, you can be pretty certain a person with MCI has the beginnings of Alzheimer’s in their brain and that disease will continue to evolve,” said Dr. Howard Chertkow, chairperson for cognitive neurology and innovation at Baycrest, an academic health-sciences center in Toronto that specializes in care for older adults.

Diagnosis. Usually, this process begins when older adults tell their doctors that “something isn’t right with my memory or my thinking” — a so-called subjective cognitive complaint. Short cognitive tests can confirm whether objective evidence of impairment exists. Other tests can determine whether a person is still able to perform daily activities successfully.

More sophisticated neuropsychological tests can be helpful if there is uncertainty about findings or a need to better assess the extent of impairment. But “there is a shortage of physicians with expertise in dementia — neurologists, geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists” — who can undertake comprehensive evaluations, said Kathryn Phillips, director of health services research and health economics at the University of California-San Francisco School of Pharmacy.

The most important step is taking a careful medical history that documents whether a decline in functioning from an individual’s baseline has occurred and investigating possible causes such as sleep patterns, mental health concerns and inadequate management of chronic conditions that need attention.

Mild cognitive impairment “isn’t necessarily straightforward to recognize, because people’s thinking and memory changes over time [with advancing age] and the question becomes ‘Is this something more than that?’” said Dr. Zoe Arvanitakis, a neurologist and director of Rush University’s Rush Memory Clinic, in Chicago.

More than one set of tests is needed to rule out the possibility that someone performed poorly because they were nervous or sleep-deprived or had a bad day. “Administering tests to people over time can do a pretty good job of identifying who’s actually declining and who’s not,” Langa said.

Progression. Mild cognitive impairment doesn’t always progress to dementia, nor does it usually do so quickly. But this isn’t well understood. And estimates of progression vary, based on whether patients are seen in specialty dementia clinics or in community medical clinics and how long patients are followed.

A review of 41 studies found that 5 percent of patients treated in community settings each year went on to develop dementia. For those seen in dementia clinics — typically, patients with more serious symptoms — the rate was 10 percent. The American Academy of Neurology’s review found that after two years 15 percent of patients were observed to have dementia.

Progression to dementia isn’t the only path that people follow. A sizable portion of patients with mild cognitive impairment — from 14 percent to 38 percent — are discovered to have normal cognition upon further testing. Another portion remains stable over time. (In both cases, this may be because underlying risk factors — poor sleep, for instance, or poorly controlled diabetes or thyroid disease — have been addressed.) Still another group of patients fluctuate, sometimes improving and sometimes declining, with periods of stability in between.

“You really need to follow people over time — for up to 10 years — to have an idea of what is going on with them,” said Dr. Oscar Lopez, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of Pittsburgh.

Specialists versus generalists. Only people with mild cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer’s should be considered for treatment with Aduhelm, experts agreed. “The question you want to ask your doctor is, ‘Do I have MCI [mild cognitive impairment] due to Alzheimer’s disease?’” Chertkow said.

Because this medication targets amyloid, a sticky protein that is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s, confirmation of amyloid accumulation through a PET scan or spinal tap should be a prerequisite. But the presence of amyloid isn’t determinative: One-third of older adults with normal cognition have been found to have amyloid deposits in their brains.

Because of these complexities, “I think, for the early rollout of a complex drug like this, treatment should be overseen by specialists, at least initially,” said Petersen of the Mayo Clinic. Arvanitakis of Rush University agreed. “If someone is really and truly interested in trying this medication, at this point I would recommend it be done under the care of a psychiatrist or neurologist or someone who really specializes in cognition,” she said.

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Judith Graham: khn.navigatingaging@gmail.com, @judith_graham

Elisabeth Rosenthal: Why we may never know if Biogen’s Alzheimer’s drug works

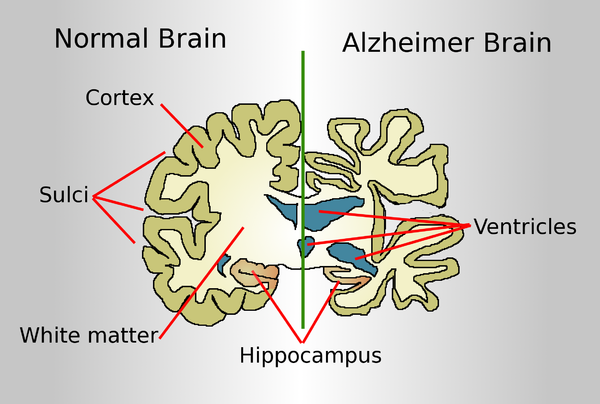

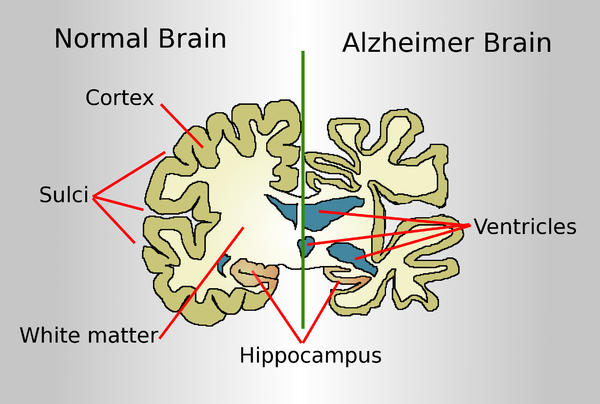

A normal brain on the left and a late-stage Alzheimer's brain on the right.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval in June of a drug purporting to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease was widely celebrated, but it also touched off alarms. There were worries in the scientific community about the drug, developed by Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen, mixed results in studies — the FDA’s own expert advisory panel was nearly unanimous in opposing its approval. And the annual $56,000 price tag of the infusion drug, Aduhelm, was decried for potentially adding costs in the tens of billions of dollars to Medicare and Medicaid.

But lost in this discussion is the underlying problem with using the FDA’s “accelerated” pathway to approve drugs for conditions such as Alzheimer’s, a slow, degenerative disease. Though patients will start taking it, if the past is any guide, the world may have to wait many years to find out whether Aduhelm is actually effective — and may never know for sure.

The accelerated approval process, begun in 1992, is an outgrowth of the HIV/AIDS crisis. The process was designed to approve for sale — temporarily — drugs that studies had shown might be promising but that had not yet met the agency’s gold standard of “safe and effective,” in situations where the drug offered potential benefit and where there was no other option.

Unfortunately, the process has too often amounted to a commercial end run around the agency.

The FDA explained its controversial decision to greenlight the Biogen pharmaceutical company’s latest product: Families are desperate, and there is no other Alzheimer’s treatment. Also, importantly, when drugs receive this type of fast-track approval, manufacturers are required to do further controlled studies “to verify the drug’s clinical benefit.” If those studies fail “to verify clinical benefit, the FDA may” — may — withdraw them.

But those subsequent studies have often taken years to complete, if they are finished at all. That’s in part because of the FDA’s notoriously lax follow-up and in part because drugmakers tend to drag their feet. When the drug is in use and profits are good, why would a manufacturer want to find out that a lucrative blockbuster is a failure?

Historically, so far, most of the new drugs that have received accelerated approval treat serious malignancies.

And follow-up studies are far easier to complete when the disease is cancer, not a neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s. In cancer, “no benefit” means tumor progression and death. The mental decline of Alzheimer’s often takes years and is much harder to measure. So years, possibly decades, later, Aduhelm studies might not yield a clear answer, even if Biogen manages to enroll a significant number of patients in follow-up trials.

Now that Aduhelm is shipping into the marketplace, enrollment in the required follow-up trials is likely to be difficult, if not impossible. If your loved one has Alzheimer’s, with its relentless diminution of mental function, you would want the drug treatment to start right now. How likely would you be to enroll and risk placement in a placebo group?

The FDA gave Biogen nine years for follow-up studies but acknowledged that the timeline was “conservative.”

Even when the required additional studies are performed, the FDA historically has been slow to respond to disappointing results.

In a 2015 study of 36 cancer drugs approved by the FDA, only five ultimately showed evidence of extending life. But making that determination took more than four years, and over that time the drugs had been sold, at a handsome profit, to treat countless patients. Few drugs are removed.

It took 17 years after initial approval via the accelerated process for Mylotarg, a drug to treat a form of leukemia, to be removed from the market after subsequent trials failed to show clinical benefit and suggested possible harm. (The FDA permitted the drug to be sold at a lower dose, with less toxicity.)

Avastin received fast-track approval as a breast cancer treatment in 2008, but three years later the FDA revoked the approval after studies showed the drug did more harm than good in that use. (It is still approved for other, generally less common cancers.)

In April, the FDA said it would be a better policeman of cancer drugs that had come to markets via accelerated approval. But time — as in delays — means money to drug manufacturers.

A few years ago, when I was writing a book about the business of U.S. medicine, a consultant who had worked with pharmaceutical companies on marketing drug treatments for hemophilia told me the industry referred to that serious bleeding disorder as a “high-value disease state,” since the medicines to treat it can top $1 million a year for a single patient.

Aduhelm, at $56,000 a year, is a relative bargain — but hemophilia is a rare disease, and Alzheimer’s is terrifyingly common. Drugs to combat it will be sold and taken. The crucial studies that will define their true benefit will take many years or may never be successfully completed. And from a business perspective, that doesn’t really matter.

Elisabeth Rosenthal, M.D., is editor of Kaiser Health News.

Harris Meyer: Amidst intense controversy, FDA approves Biogen’s Alzheimer's drug

Drawing comparing a normal aged brain (left) and the brain of a person with Alzheimer's (right). Characteristics that separate the two are pointed out.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, a drug developed by Biogen, which is based in Cambridge’s Kendall Square neighborhood. But the approval highlights a deep division over the drug’s benefits as well as criticism about the integrity of the FDA approval process.

The approval of aducanumab came despite a near-unanimous rejection of the product by an FDA advisory committee of outside experts in November. Doubts were raised when, in 2019, Biogen halted two large clinical trials of the drug after determining it wouldn’t reach its targets for efficacy. But the drugmaker later revised that assessment, stating that one trial showed that the drug reduced the decline in patients’ cognitive and functional ability by 22 percent.

Some FDA scientists in November joined with the company to present a document praising the intravenous drug. But other FDA officials and many outside experts say the evidence for the drug is shaky at best and that another large clinical trial is needed. A consumer advocacy group has called for a federal investigation into the FDA’s handling of the approval process for the product.

A lot is riding on the drug for Biogen. It is projected to carry a $50,000-a-year price tag and would be worth billions of dollars in revenue to the Cambridge company.

The FDA is under pressure because an estimated 6 million Americans are diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, a debilitating and ultimately fatal form of dementia, and there are no drugs on the market to treat the underlying disease. Although some drugs slightly mitigate symptoms, patients and their families are desperate for a medication that even modestly slows its progression.

Aducanumab helps the body produce antibodies that remove amyloid plaques from the brain, which has been associated with Alzheimer’s. It’s designed for patients with mild-to-moderate cognitive decline from Alzheimer’s, of which there are an estimated 2 million Americans. But it’s not clear whether eliminating the plaque improves brain function in Alzheimer’s patients. So far, nearly two dozen drugs based on the so-called amyloid hypothesis have failed in clinical trials.

Besides questions about whether the drug works, there also are safety issues. More than one-third of patients in one of the trials experienced brain swelling and nearly 20 percenty had brain bleeding, though those symptoms generally were mild and controllable. Because of those risks, patients receiving aducanumab have to undergo regular brain monitoring through expensive PET scans and MRI tests.

Some physicians who treat Alzheimer’s patients say they won’t prescribe the drug even if it’s approved.

“There’s a lot of hope among my patients that this is going to be a game changer,” said Dr. Matthew Schrag, an assistant professor of neurology at Vanderbilt University. “But the cognitive benefits of this drug are quite small, we don’t know the long-term safety risks, and there will be a lot of practical issues in deploying this therapy. We have to wait until we’re certain we’re doing the right thing for patients.”

Many aspects of aducanumab’s journey through the FDA approval process have been unusual. It’s “vanishingly rare” for a drug to continue on toward approval after its clinical trial was halted because unfavorable results showed that further testing was futile, said Dr. Peter Lurie, president of the Center for Science in the Public Interest and a former FDA associate commissioner. And it’s “mind-boggling,” he added, for the FDA to collaborate with a drugmaker in presenting a joint briefing document to an FDA advisory committee.

“A joint briefing document strikes me as completely inappropriate and an abdication of the FDA’s claim to being the best regulatory agency in the world,” Lurie said.

Three FDA advisory committee members who voted in November against approving the drug wrote in a recent JAMA commentary that the FDA’s “unusual degree of collaboration” with Biogen led to criticism that it “potentially compromised the FDA’s objectivity.” They cast doubt on both the drug’s safety and the revised efficacy data.

The FDA and Biogen declined to comment for this article.

Despite the uncertainties, the Alzheimer’s Association, the nation’s largest Alzheimer’s patient advocacy group, has pushed hard for FDA approval of aducanumab, mounting a major print and online ad campaign last month. The “More Time” campaign featured personal stories from patients and family members. In one ad, actor Samuel L. Jackson posted on Twitter, “If a drug could slow Alzheimer’s, giving me more time with my mom, I would have read to her more.”

But the association has drawn criticism for having its representatives testify before the FDA in support of the drug without disclosing that it received $525,000 in contributions last year from Biogen and its partner company, Eisai, and hundreds of thousands of dollars more in previous years. Other people who testified stated upfront whether or not they had financial conflicts.

Dr. Leslie Norins, founder of a group called Alzheimer’s Germ Quest that supports research, said the lack of disclosure hurts the Alzheimer’s Association’s credibility. “When the association asks the FDA to approve a drug, shouldn’t it have to reveal that it received millions of dollars from the drug company?” he asked.

But Joanne Pike, the Alzheimer’s Association’s chief strategy officer, who testified before the FDA advisory committee about aducanumab without disclosing the contributions, denied that the association was hiding anything or that it supported the drug’s approval because of the drugmakers’ money. Anyone can search the association’s website to find all corporate contributions, she said in an interview.

Pike said her association backs the drug’s approval because its potential to slow patients’ cognitive and functional decline offers substantial benefits to patients and their caregivers, its side effects are “manageable,” and it will spur the development of other, more effective Alzheimer’s treatments.

“History has shown that approvals of first drugs in a category benefit people because they invigorate the pipeline,” she said. “The first drug is a start, and the second and third and fourth treatment could do even better.”

Lurie disputed that. He said lowering the FDA’s standards and approving an ineffective or marginally effective drug merely encourages other manufacturers to develop similar, “me too” drugs that also don’t work well.

Anne Saint says she wouldn’t have risked putting her husband, Mike Saint, on the new Alzheimer’s drug aducanumab because of safety issues. Mike died in September at age 71. (MOLLY SAINT)

The Public Citizen Health Research Group, which opposes approval of aducanumab, has called for an investigation of the FDA’s “unprecedented and inappropriate close collaboration” with Biogen. It asked the inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services to probe the approval process, which that office said it would consider.

The group also urged the acting FDA commissioner, Dr. Janet Woodcock, to remove Dr. Billy Dunn, an aducanumab advocate who testified about it to the advisory committee, from his position as director of the FDA’s Office of Neuroscience and hand over review of the drug to staffers who weren’t involved in the Biogen collaboration.

Woodcock refused, saying in a letter that FDA “interactions” with drugmakers make drug development “more efficient and more effective” and “do not interfere with the FDA’s independent perspective.”

Although it would be unusual for the FDA to approve a drug after rejection by an FDA advisory committee, it’s not unprecedented, Lurie said. Alternatively, the agency could approve it on a restricted basis, limiting it to a segment of the Alzheimer’s patient population and/or requiring Biogen to monitor patients.

“That will be tempting but shouldn’t be the way the problem is solved,” he said. “If the product doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. Once it’s on the market, it’s very difficult to get it off.”

If the drug is approved, Alzheimer’s patients and their families will have to make a difficult calculation, balancing the limited potential benefits with proven safety issues.

Anne Saint, whose husband, Mike, had Alzheimer’s for a decade and died in September at age 71, said that based on what she’s read about aducanumab, she wouldn’t have put him on the drug.

“Mike was having brain bleeds anyway, and I wouldn’t have risked him having any more side effects, with no sure positive outcome,” said Saint, who lives in Franklin, Tenn. “It sounds like maybe that drug’s not going to work, for a lot of money.”

Their adult daughter, Sarah Riley Saint, feels differently. “If this is the only hope, why not try it and see if it helps?” she said.

Harris Meyer is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Biogen to spend $250 million to get off fossil fuels

— Biogen logo

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Biogen, the big, Cambridge-based biotech company, has committed $250 million in investment to eliminate fossil fuels from Biogen operations. The initiative also includes collaboration with renowned institutions to improve the health of the world’s most vulnerable populations who are often adversely affected by fossil-fuel emissions.

“Biogen achieved carbon neutrality in 2014, and the new initiative is part of a concerted effort to advance positive environmental change. The company plans to eliminate its use of fossil fuels by 2040 and will continue to invest in initiatives to study the impact of fossil fuels on human health. With this investment, Biogen has become the first Fortune 500 company to commit to eliminating all reliance on fossil fuels by 2040.

“‘Our Healthy Climate, Healthy Lives initiative further builds on Biogen’s long-standing strategy to deal with climate change by addressing the interrelated challenges of climate and health, including in the realm of brain health,’ said Michel Vounatsos, CEO of Biogen. ‘Biogen was the first company in the life sciences industry to become carbon neutral. We believe that it is time to take even greater action by implementing a well-defined program that examines how we live, how we do business and how we consume energy. By doing so, Biogen will play its part to address and impact dramatic health disparities among people around the world, as well as build a stronger, more sustainable future for all.”’