Michelle Andrews: Sanders is right to assert that millions can’t find a physician

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) has long been a champion of a government-sponsored “Medicare for All” health program to solve long-standing problems in the United States, where we pay much more for health care than people in other countries but are often sicker and have a shorter average life expectancy.

Still, he realizes his passion project has little chance in today’s political environment. “We are far from a majority in the Senate. We have no Republican support … and I’m not sure that I could get half of the Democrats on that bill,” Sanders said in recent remarks to community health advocates.

He has switched his focus to include, among other things, expanding the primary-care workforce.

Sanders introduced has introduced legislation that would invest $100 billion over five years to expand community health centers and provide training for primary-care doctors, nurses, dentists, and other health professionals.

“Tens of millions of Americans live in communities where they cannot find a doctor while others have to wait months to be seen,” he said when the bill was introduced. He noted that this scenario not only leads to more human suffering and unnecessary deaths “but wastes tens of billions a year” because people who “could not access the primary care they need” often end up in emergency rooms and hospitals.

Is that true? Are there really tens of millions of Americans who can’t find a doctor? We decided to check it out.

Our first stop was the senator’s office to ask for the source of that statement. But no one answered our query.

Primary Care, by the Numbers

So we poked around on our own. For years, academic researchers and policy experts have debated and dissected the issues surrounding the potential scarcity of primary care in the United States. “Primary care desert” and “primary care health professional shortage area” are terms used to evaluate the extent of the problem through data — some of which offers an incomplete impression. Across the board, however, the numbers do suggest that this is an issue for many Americans.

The Association of American Medical Colleges projects a shortage of up to 48,000 primary-care physicians by 2034, depending on variables like retirements and the number of new physicians entering the workforce.

How does that translate to people’s ability to find a doctor? The federal government’s Health Resources and Services Administration publishes widely referenced data that compares the number of primary care physicians in an area to its population. For primary care, if the population-to-provider ratio is generally at least 3,500 to 1, it’s considered a “health-professional shortage area.”

Based on that measure, 100 million people in the United States live in a geographic area, are part of a targeted population, or are served by a health care facility where there is a shortage of primary-care providers. If they all want doctors and cannot find them, that figure would be well within Sanders’ “tens of millions” claim.

The metric is a meaningful way to measure the impact of primary care, experts said. In those areas, “you see life expectancies of up to a year less than in other areas,” said Russ Phillips, a physician who is director of Harvard Medical School’s Center for Primary Care. “The differences are critically important.”

Another way to think about primary-care shortages is to evaluate the extent to which people report having a usual source of care, meaning a clinic or doctor’s office where they would go if they were sick or needed health-care advice. By that measure, 27 percent of adults said they do not have such a location or person to rely on or that they used the emergency room for that purpose in 2020, according to a primary-care score card published by the Milbank Memorial Fund and the Physicians Foundation, which publish research on health care providers and the health care system.

The figure was notably lower in 2010 at nearly 24 percent, said Christopher Koller, president of the Milbank Memorial Fund. “And it’s happening when insurance is increasing, at the time of the Affordable Care Act.”

The U.S. had an adult population of roughly 258 million in 2020. Twenty-seven percent of 258 million reveals that about 70 million adults didn’t have a usual source of care that year, a figure well within Sanders’ estimate.

Does Everyone Want This Relationship?

Still, it doesn’t necessarily follow that all those people want or need a primary-care provider, some experts say.

“Men in their 20s, if they get their weight and blood pressure checked and get screened for sexually transmitted infections and behavioral risk factors, they don’t need to see a regular clinician unless things arise,” said Mark Fendrick, an internal-medicine physician who is director of the University of Michigan Center for Value-Based Insurance Design.

Not everyone agrees that young men don’t need a usual source of care. But removing men in their 20s from the tally reduces the number by about 23 million people. That leaves 47 million without a usual source of care, still within Sanders’ sbroad “tens of millions” claim.

In his comments, Sanders refers specifically to Americans being unable to find a doctor, but many people see other types of medical professionals for primary care, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

Seventy percent of nurse practitioners focus on primary care, for example, according to the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. To the extent that these types of health professionals absorb some of the demand for primary-care physician services, there will be fewer people who can’t find a primary-care provider, and that may put a dent in Sanders’ figures.

Finally, there’s the question of wait times. Sanders asserts that people must wait months before they can get an appointment. A survey by physician-staffing company Merritt Hawkins found that it took an average of 20.6 days to get an appointment for a physical with a family physician in 2022. But that figure was 30 percent lower than the 29.3-day wait in 2017. Geography can make a big difference, however. In 2022, people waited an average of 44 days in Portland, Ore., compared with eight days in Washington, D.C.

Our Ruling

Sanders’s assertion that there are “tens of millions” of people who live in communities where they can’t find a doctor aligns with the published data we reviewed. The federal government estimates that 100 million people live in areas where there is a shortage of primary care providers. Another study found that some 70 million adults reported they don’t have a usual source of care or use the emergency department when they need medical care.

At the same time, several factors can affect people’s primary-care experience. Some may not want or need to have a primary-care physician; others may be seen by non-physician primary care providers.

Finally, on the question of wait times, the available data does not support Sanders’s claim that people must wait for months to be seen by a primary care provider. There was wide variation depending on where people lived, however.

Overall, Sanders accurately described the difficulty that tens of millions of people likely face in finding a primary-care doctor.

We rate it Mostly True.

Michelle Andrews is a reporter for KFF Health News.

Victoria Knight: Sanders tries gambit to allow pharmaceutical imports from Canada and U.K.

The Haskell Free Library and Opera House straddles the border in Derby Line, Vt., and Stanstead, Quebec.

Harmony is not often found between two of the most boisterous senators on Capitol Hill, Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rand Paul (R-Ky.).

But it was there at June 14 Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee markup of legislation to reauthorize the Food and Drug Administration’s user fee program, which is set to expire Sept. 30.

This user fee program, which was first authorized in 1992, allows the FDA to collect fees from companies that submit applications for drug approval. It was designed to speed the approval review process. And it requires reauthorization every five years.

Congress considers this bill a must-pass piece of legislation because it’s used to help fund the FDA, as well as revamp existing policies. As a result, it also functions as a vehicle for other proposals to reach the president’s desk — especially those that couldn’t get there on their own.

And that’s why, on that day Sanders took advantage of the must-pass moment to propose an amendment to the user fee bill that would allow for the importation of drugs from Canada and the United Kingdom, and, after two years, from other countries.

Prescription medications are often much less expensive in other countries, and surveys show that millions of Americans have bought drugs from overseas — even though doing so is technically illegal.

“We have talked about reimportation for a zillion years,” said a visibly heated Sanders. “This bill actually does it. It doesn’t wait for somebody in the bureaucracy to make it happen. It actually makes it happen.” He then went on for several minutes, his tone escalating, citing statistics about high drug prices, recounting anecdotes of people who traveled for drugs, and ending with outrage about pharmaceutical companies’ campaign contributions and the number of lobbyists the industry has.

“I always wanted to go to a Bernie rally, and now I feel like I’ve been there,” Paul joked after Sanders finished talking. He went on to offer his support for the Vermont senator’s amendment — a rare bipartisan alliance between senators who are on opposite ends of the political spectrum.

“This is a policy that sort of unites many on both sides of the aisle, the outrage over the high prices of medications,” added Paul. He said he didn’t support drug-price controls in the U.S. but did support a worldwide competitive free market for drugs, which he believes would lower prices.

Even before Sanders offered his amendment, the user fee bill before the committee included a limited drug-importation provision, Sec. 906. It would require the FDA to develop regulations for importing certain prescription drugs from Canada. But how this provision differs from a Trump-era regulation is unclear, said Rachel Sachs, a professor of law at Washington University in St. Louis and an expert on drug pricing.

“FDA has already made importation regulations that were finalized at the end of the Trump administration,” said Sachs. “We haven’t seen anyone try to get an approval” under that directive. She added that whether Sec. 906 is doing anything to improve the existing regulation is unclear.

Sanders’s proposed amendment would have gone further, Sachs explained.

It would have included insulin among the products that could be obtained from other countries. It also would have compelled pharmaceutical companies to comply with the regulation. It has been a concern in drug-pricing circles that even if importation were allowed, there would be resistance to it in other countries, because of how the practice could affect their domestic supply.

A robust discussion between Republican and Democratic senators ensued. Among the most notable moments: Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) asked whether importing drugs from countries with price controls would translate into a form of price control in the U.S. Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) said his father breaks the law by getting his glaucoma medication from Canada.

The committee’s chair, Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), held the line against Sanders’s amendment. Although she agreed with some of its policies, she said, she wanted to stick to the importation framework already in the bill, rather than making changes that could jeopardize its passage. “Many of us want to do more,” she said, but the bill in its current form “is a huge step forward, and it has the Republican support we need to pass legislation.”

“To my knowledge, actually, this is the first time ever that a user fee reauthorization bill has included policy expanding importation of prescription drugs,” Murray said. “I believe it will set us up well to make further progress in the future.”

Sen. Richard Burr (R-N.C.), the committee’s ranking member, was adamant in his opposition to Sanders’s amendment, saying that it spelled doom for the legislation’s overall prospects. “Want to kill this bill? Do importation,” said Burr.

Sanders, though, staying true to his reputation, didn’t quiet down or give up the fight. Instead, he argued for an immediate vote. “This is a real debate. There were differences of opinions. It’s called democracy,” he said. “I would urge those who support what Sen. Paul and I are trying to do here to vote for it.”

In the end, though, committee members didn’t, opting to table the amendment, meaning it was set aside and not included in the legislation.

Later in the afternoon, the Senate panel reconvened after senators attended their weekly party policy lunches and passed the user fee bill out of the committee 13-9. The next step is consideration by the full Senate. A similar bill has already cleared the House.

Victoria Knight is a Kaiser Health News reporter

Don Pesci: Sanders may press his campaign for socialism to the convention

Bernie Sanders last month

VERNON, Conn.

The last word, or the next to the last word, on Vermont socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders’ ill-fated run for the presidency may be that of communist evangelist Karl Marx. In The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte Marx writes, “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great, world-historical facts and personages occur, as it were, twice. He has forgotten to add: the first time as tragedy, the second as farce.”

This is the second time that Sanders has run for president, succumbing the first time to Barack Obama’s former secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, and this time to former Vice President Joe Biden. This, his second and one suspects last run for the presidency – Sanders is getting on in years -- may be a tragedy to the youth of the nation, who hung on his every word, but it is a farce for most grownups.

Sanders announced that he was leaving the Democrat primary race on April 8, but his announcement only meant that Sanders was out, not down. In Connecticut, he may remain on the ballot because under state law, according to a story in CTMirror, “Secretary of the State Denise Merrill cannot cancel a primary without the written permission of candidates who have qualified for the ballot.” Merrill is yet awaiting permission from Sanders to suspend the costly Democrat presidential primary.

Even though Sanders has thrown in the sponge, the socialist millionaire (in assets) still wants to amass a minor fortune in Democrat delegates. Sanders is determined to use his delegates to the Democratic Convention to bend his party toward a glorious socialist future, and some within the party of Jefferson, Jackson and the late Connecticut Democratic leader John Bailey are now wondering whether the man ever wanted to be president. There are two broad reasons why men and women of good will enter the Democratic primary presidential lists: 1) to become president and, 2) to make a point. Sanders has now conceded for the second time that he has not enough delegate votes to deny his presidential primary opponent the nomination. Presumably, after the nominating convention, Sanders will throw his support to Biden, as previously he had done with Clinton.

But there is a thorn in the rose bouquet, or the shadow of a thorn. It’s obvious that Sanders wants to be a commanding presence at the Democrat nominating convention. Will he withhold an endorsement of Biden if the Sanders gang is not adequately represented in the nominating convention plank? If Democrats move to the traditional Democratic center in hopes of retaining votes in the general election, will Sanders open a campaign as an independent, socialist candidate for the presidency?

Though these questions have not been asked of Sanders, they begged to be answered, largely because of the manner in which Sanders has conceded a primary win to Biden. Sanders is running to score ideological points – and, more importantly, to move his sluggish party to a socialist position from which it cannot easily withdraw. Unlike Eugene Debs, for instance, Sanders is not now, and perhaps has never been, interested in running the country as socialist president.

Sanders’s thumbprint on his party have caused some agita in Connecticut’s Democratic Party, which has been trending progressive/socialist for many years. Merrill notes that Sanders has ceded the nomination to Biden. “That for me,” she has said, “effectively ends the justification for holding a primary in Connecticut. Now, the results are predetermined. Then comes the announcement he [Sanders] will remain on the ballot, which hopefully he will reconsider.”

But acknowledging that he has not enough delegates to win the nomination does not mean that Sanders has pledged his delegates to Biden. That could happen at the Democratic convention – if the Democrat platform incorporates Biden’s ideological predispositions. And if not – well, there’s the thorn in the rose. It’s altogether possible that Sanders might flee the convention with his deluges in hand and challenge Biden as an independent candidate for president in the general election. Progressive ex-president Teddy Roosevelt did just that when the Republican nominating convention in 1912 gave its presidential endorsement to William Howard Taft. Roosevelt’s defection from the Republican Party marked a major step for progressivism in the United States.

If Sanders is a serious socialist, why should he not follow the same course?

Merrill, a faithful Democrat in arms, is justifiably concerned with the cost to her party of what she regards as an unnecessary Democratic presidential primary in Connecticut.

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn.-based columnist.

Peter Certo: So capitalism naturally goes with democracy? Do some research

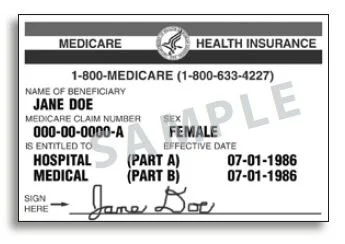

Medicare is a socialistic idea.

From OtherWords.org

For decades, Republicans have painted anyone left of Barry Goldwater as a “socialist.” Why? Because for a generation raised on the Cold War, “socialist” just seemed like a damaging label.

And, probably, it was.

You can tell, because many liberal-leaning figures internalized that fear. When Donald Trump vowed that “America will never be a socialist country,” for instance, no less than Sen. Elizabeth Warren agreed.

But while older Americans retain some antipathy toward the word, folks raised in the age of “late capitalism” don’t. In Gallup polls, more millennial and Gen-Z respondents say they view “socialism” positively with each passing year, while their opinion of “capitalism” tumbles ever downward.

As a result, it’s not all that surprising that self-described democratic socialist Senator Bernie Sanders tops Trump in most head to head polls.

Still, old propaganda dies hard. What else could explain the panicky musings of Chris Matthews, the liberal-ish former MSNBC host, who recently wondered aloud if a Sanders victory would mean “executions in Central Park”?

Nevermind that Sanders is a longtime opponent of all executions, as any news host could surely look up. The real issue is a prejudice, particularly among Americans reared on fears of the Soviet Union and Maoist China, that “socialism” implies dictatorship, while “capitalism” presumes democracy.

Their Cold War education serves them poorly.

Yes, it’s easy to name calamitous dictatorships, living and deceased, that proclaim socialist or communist commitments. But it’s just as easy to point to Europe, where democratic socialist parties and their descendants have been mainstream players in democratic politics for a century or longer.

The health-care, welfare, and tax systems built by those parties have created societies with far greater equality, higher social mobility, and better health outcomes (at lower cost) than we enjoy here. These systems aren’t perfect, but to a significant degree they’re more democratic than our own.

But we don’t have to look abroad (or to Vermont) for a rich social democratic history.

Milwaukee Mayor Daniel Hoan — one of several socialists to govern the city — served for 24 years, and built the country’s first public busing and housing programs. And ruby-red North Dakota is, even now, the only state in the country with a state-owned bank, thanks to a socialist-led government in the early 20th Century. Today, dozens of elected socialists hold office at the state or municipal levels.

While plenty of socialists embraced democracy, plenty of capitalists turned to dictatorship.

In the name of fighting socialism during the Cold War, the U.S. trained and supported members of right-wing death squads in El Salvador, genocidal army units in Guatemala, and a Chilean military regime that disappeared or tortured tens of thousands of people while enacting “pro-market reforms.”

Only last year, the U.S. government was cheering a military coup against an elected socialist government in Bolivia. And in 2018, The Wall Street Journal praised far-right Brazilian leader Jair Bolsonaro, an apologist for the country’s old military regime, for his deregulation of business.

Even here at home, our capitalist “freedoms” have co-existed peacefully with racial apartheid, the world’s largest prison system, and the mass internment of immigrants and their children.

Sanders has been clear his socialist tradition comes from the social democratic systems common in countries like Denmark, with their provisions for universal health care and free college.

Should Matthews next wonder aloud if candidates who oppose Medicare for All or free college also support death squads, genocide, mass incarceration, or internment camps? If that sounds unfair, then so should the lazy fear mongering we get about “socialism.”

The sobering truth is that all political systems are capable of either great violence or social uplift. That’s why we need resilient social movements, whatever system we use — and why we’re poorly served by propaganda from any corner..

Peter Certo is the editorial manager of the Institute for Policy Studies and editor of OtherWords.org.

Brian Wakamo: Save Minor League Baseball teams

Home of the Vermont Lake Monsters, a Minor League Baseball affiliate of the Oakland Athletics

Via OtherWords.org

Baseball had an exciting year — breakout stars, a major cheating scandal, a seven-game World Series.

And now it’s capping off the year with a disastrous idea from the owners. Led by the Houston Astros — the same Astros mired in scandals over cheating and domestic violence — Major League Baseball has proposed cutting 42 minor league teams all around the country.

Who’s on the chopping block? Teams from Quad Cities, Iowa, and Williamsport, Penn., where the Little League World Series takes place every year, to Missoula, Montana and Orem, Utah.

These places have, in many cases, been a part of the fabric of baseball in America for over a century. The Vermont Lake Monsters, in Burlington (on Lake Champlain), another team on the “hit list,” play in a stadium built in 1906, older than Fenway Park. The similarly targeted Hagerstown (MD) Suns play in one built in 1930.

These teams have provided a way for folks in rural and underserved areas to see baseball and future major leaguers for a fraction of the price of traveling to an MLB city. And they’re a way to boost the communities they play in.

Compensation for these players is often ridiculously low — around the poverty line — and they don’t have a union like their professional counterparts. It’s a cutthroat and competitive environment, with only about one in ten minor leaguers making it to the majors. And with low per diems and intensive travel, it’s an exhausting endeavor.

These issues need to be addressed not only to ensure the survival of Minor League Baseball, but to help baseball itself thrive. Players aren’t going to become their best if they’re stuck on futons in host families’ homes, living off PB&J sandwiches.

But the solution is not to destroy the teams — and the local communities — who give them the chance in the first place. No wonder the proposal has been criticized by folks all over the political spectrum.

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders wrote a letter to MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred protesting the move. And over 100 representatives — from Congressional Progressive Caucus leaders Mark Pocan (D.-WI) and Jamie Raskin (D-MD.) to Trump supporters Elise Stefanik (R-N.Y.) and Greg Gianforte (R.-Calif.)— signed on to a letter condemning the MLB’s hit list.

MLB has tried to justify the cuts in the name of cost savings, low attendance, and stadiums that fail to meet MLB standards. In reality, it’s rooted in greed and a desire for more profits — and it will backfire.

These teams employ 1,000 players and countless more workers, and the Minor Leagues saw over 40 million fans attend their games. At a time when the MLB is wringing its hands about attendance (now at a 16-year low while young fans are tuning in to other sports), eliminating this link to 42 communities would be deeply harmful.

Even so, major league teams in relatively modest markets like Kansas City are getting sold for $1 billion, and the MLB is making record revenues thanks to television deals. Meanwhile, they have the gall to balk at requests for higher minor league salaries, while demanding minor league franchises pay for every part of their teams, which train those major leaguers.

It’s ridiculous. The MLB should be investing in these teams and players, so they’re not stuck on poverty wages and couches — and helping these historic stadiums endure for another hundred years. Baseball isn’t called America’s pastime for nothing, and these teams in locales all around the U.S. are a huge reason for that.

The MLB’s greed is wrong and destructive. Let’s build up the minor leagues, not cut them down.

Brian Wakamo is an inequality researcher at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Llewellyn King: A big Warren weakness -- she always takes the bait

Sen. Elizabeth Warren

The Democratic deep state – it is not made up of Democrats in the bureaucracies, but rather those who make up the core of the party -- is in agony.

Solid, middle-of-the-road, fad-proof Democrats are not happy. They are the ones most likely to have thrown their support early to Joe Biden, and who now are eyeing Elizabeth Warren with apprehension and a sense of the inevitable.

Warren exhibits all the weaknesses of someone who, at her core, is not a professional politician. She blunders into traps whether they are set for her or not. She is vulnerable to the political equivalent of fatal attraction.

Biden lurches from gaffe to gaffe and is haunted by the positions he took a long time ago. Some of his social positions turn out to be like asbestos: decades ago, seen as a cure-all building material, now lethal.

Where Biden stumbles over the issues of the past, Warren walks into the traps of today. She is one of those self-harming politicians who shoots before she takes aim.

When Donald Trump mocked her claims of Native American ancestry, Warren took the bait and ended with a hook in her gullet. A more seasoned politician would not have been goaded by a street fighter into taking a DNA test, resulting in an apology. Ignorance met incaution and Trump won.

Warren also swallowed the impeachment bait of the left, ignoring the caution of centrists who worried about the outcome in an election year. If the Senate acquits, Trump claims exoneration.

Then there is the Medicare for All trap into which Warren not so much fell as she propelled herself. Because Bernie Sanders, who reminds me of King Lear, and his field commander Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and others on the left favored it, Warren had to leap in, ill-prepared.

The prima facie logic is there, but the mechanism is not. It is easy to see that Medicare is a very popular program that works. It is also easy to see that the United States pays more than twice as much on health care as any other nation.

Those, like myself, who have experienced state systems abroad, as well a Medicare at home, know the virtues of the single-payer system with patient-chosen, private insurance on the top for private hospital rooms, elective surgery and pampering that is not basic medicine. But we also know that the switch to Medicare for All would be hugely dislocating.

Employer-paid health care is a tax on business but substituting that with a straight tax is politically challenging, structurally difficult, and impossible to sell at this stage in the evolution of health care. It likely will give a new Democratic president a constitutional hernia.

Warren seems determined to embrace the one thing that makes the left and its ideas electorally vulnerable: The left wants to tell the electorate what it is going to take away.

Consider this short list of the left’s confiscations which the centrists must negotiate, not endorse: We want your guns, we want your employer-paid health care, we want your gasoline-powered car, and we want the traditional source of your electricity. Trust us, you will love these confiscations.

Those are the position traps for Warren. To make a political sale -- or any sale – do not tell the customers what you are going to take away from them.

It is well known that Republicans roll their eyes in private at the mention of Trump, while supporting him in public. Democratic centrists -- that place where the true soul of a party resides, where its expertise dwells, and where its most thoughtful counsel is to be heard -- roll their eyes at the mention of all the leading candidates. They like Pete Buttigieg but think him unelectable. If elected, they worry that Warren would fall into the traps set for her around the world -- as Trump has with Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping and Kim Jong-un.

Politics needs passion. “She is better than Trump,” is not a passionate rallying cry.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Don Pesci: The rhetorical career of Bernie Sanders, socialist

Sen. Bernie Sanders

It is no longer true, as your mother may once have told you, that you are judged by the company you keep. Former President Barack Obama had a few diamonds in the rough on his friends list. There were the Chicago terrorist bombers Bill Ayers, a former leader of the Weather Underground, now an American elementary education theorist, and his wife Bernadine Dohrn, responsible for bombings of the U.S. Capitol, the Pentagon and several police stations in New York, as well as the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion that killed three of its members. Dohrn left a position in 2013 as “Clinical Associate Professor of Law" at the Northwestern University School of Law.

Far from being a repentant sinner, Ayres told The New York Times in 2001 "I don't regret setting bombs. I feel we didn't do enough." Ayers and Obama served together on the board of directors for the Woods Fund of Chicago, their terms overlapping for three years, and Ayres is credited with helping to jump-start Obama’s political career. In 1995, Alice Palmer introduced Obama as her chosen successor in the Illinois State Senate at a gathering held in the Ayers home.

Obama also attended for 20 years the Rev. Jeremiah Wright’s Chicago church where, apparently, he snoozed through sermons such as "Confusing God and Government" in which Wright dammed America. Wright officiated at the wedding ceremony of Barack and Michelle Obama and baptized their children. The title of Obama's 2006 memoir, The Audacity of Hope, was inspired by a Wright sermon.

Wright claimed his offending message had been taken out of context, to which Salon editor-in-chief Joan Walsh responded: "the whole idea that Wright has been attacked over 'sound bites,' and if Americans saw his entire sermons, in context, they'd feel differently, now seems ludicrous. The long clips [Bill] Moyers played only confirm what was broadcast in the snippets… My conclusion Friday night was bolstered by new tapes of Wright that came out this weekend, including one that captures him saying the Iraq war is 'the same thing al-Qaida is doing under a different color flag,' and a much longer excerpt from the 'God damn America' sermon that denounces 'Condoskeezer Rice ...”

Obama’s past associations certainly presented no bar to his accession to the presidency.

It is doubtful that Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ unsavory past and present associations will figure negatively in his own presidential bid. Assuming that Sanders wins the Democrat primary campaign and goes toe to toe with President Trump in a general election, he may find it difficult to grouse, after losing, that Russian spooks spiked his campaign because they preferred Trump to Sanders, the Hillary Clinton gambit.

Sanders, after all, spent his honeymoon in Russia in 1988 during the bad old days of Soviet Imperialism where, under the influence of vodka, he belted out Woody Guthrie’s ancient anthem “This Land Is Your Land.” Then too, Sanders is a socialist anti-capitalist dragon, belching fire out of his snout every half hour. One year after his Moscow honeymoon, Sanders visited Cuba, and his praise of Castro – a puff adder who was smoking gays and persecuting black Cubans at the time, not to mention the petite bourgeois small “d” democrats littering Castro’s jails -- was effusive.

Sanders, who was a congressman and the mayor of Burlington, Vt., before being elected to the Senate, did pause in his praise to note Cuba’s “enormous deficiencies” in human rights. How could he help but notice? In the United States, freedom-loving radicals like Sanders, longing to bow before the socialist shrine, bit their smothering tongues, but most of them were not shameless enough to throw bouquets at the feet of men like gods. Sanders declared he never saw a hungry child or a homeless person while in Cuba, but he did see a revolution “that is far deeper and more profound than I understood it to be.” One can hardly expect Russian President Vladimir Putin to disagree with Sanders’ pro-socialist leanings.

Senior adviser to Sanders presidential campaign Heather Gautney is convinced that “Today’s neoliberal capitalist system has become utterly incompatible with the requisites of democratic freedom.” High unemployment, Gautny said on an Iranian TV show, is a blessing because it gives people more down time to engage in protest movements. And Sanders speech writer David Sirota wrote glowingly about “Hugo Chavez’s Economic Miracle” in 2013, just as food shortages were “beginning to surface in Caracas and the countryside,” according to a piece in the Washington Times.

As a young man, Sanders should have been studying Churchill – “Socialism is the philosophy of failure, the creed of ignorance and the gospel of envy,” a near perfect description of the last ten stump-speeches of Sanders and Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren. But Sanders’ ideological antennae were tuned to the Soviet Union, where he spent his honeymoon. The embrace of the indefensible is fatal in the long run, but in the short run, it is an indispensable element in the rise of autocrats. And in the long run, people who have lost an animating, democratic virtue long only to sleep under the warm, benevolent smile of a dictator.

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn.-based columnist.

Don Pesci: Where Bernie Sanders's utopian dreams would end up

New Harmony, a utopian project in Harmony Township, Ind., as envisioned by Robert Owen. (1771-1858).

Empty shelves in a supermarket in Venezuela, which is led by socialist dictator Nicolas Maduro.

If you want a vision of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever”

– George Orwell.

CBS News has announced that the "Medicare for All" bill of Vermont’s socialist senator, Bernie Sanders, would, according to Sanders himself, "get rid of insurance companies and drug companies making billions of dollars in profit every single year." The bill is a universal health care, one size fits all, tax financed, proposal. Connecticut's U.S. Sen. Dick Blumenthal, CTMirror reports, was one of 14 co-sponsors of Sanders’s bill.

“In my view,” Sanders said of his bill, “the current debate over 'Medicare for All' really has nothing to do with health care. It’s all about greed and profiteering. It is about whether we maintain a dysfunctional system which allows the top five health insurance companies to make over $20 billion in profits last year.”

But, of course, the Sanders bill has everything to do with health care. If adopted into law, it would effectively abolish insurance companies. Sanders himself has said that his "Medicare for All" scheme would "get rid of insurance companies and drug companies making billions of dollars in profit every single year.”

Reducing the insurance industry to rubble in an effort to curb profits that Sanders considers obscene is a bit like burning down the house to rid the living room of a mouse, or cutting off your nose to spite the fly on it.

For the thoroughgoing socialist however, all profits, exorbitant or not, are obscene.

The two socialist autocrats in Venezuela, Hugo Chavez and Nicolás Maduro, nationalized profits and, a few years after socialist hero Chavez had assumed room temperature, toilet paper in Venezuela disappeared, as did food and medicine. Disappearing products and services in perfected socialist states are replaced with armed soldiers, a disarmed populace, brown shirts and fists, not to mention draconian punishments for anyone who presumes to question an omnipotent and omnipresent state.

Sanders is a socialist by trade and inclination, and socialists abhor company profits, without which industries could not stay in business. Adolf Hitler, a white national socialist, solved the profit problem by incorporating businesses into his fascist program. Like communism, fascism is a perfection of the socialist idea. Both Hitler and Mussolini were socialists before they settled comfortably into fascism. Mussolini perfectly defined the fascist credo in the following terms: “Everything in the state, nothing outside the state, nothing above the state.”

He might easily have been describing Stalin’s Russia, or Maduro’s Venezuela, or the future utopia of Bernie Sanders. Mussolini certainly was not describing the average conservative/libertarian view of the proper role of government, which is to pursue policies that promote the general welfare – not the same thing as imprisoning the general populace in welfare penitentiaries.

The perfecting of Sanders’ s socialist scheme necessitates a hostile takeover of the insurance industry by the socialist administrative state. But this is only the beginning. If insurance profits are verboten to committed socialists, why should the energy industry, also profitable, survive the attentions of Sanders/Blumenthal, or the real estate industry, Blumenthal’s own golden goose? Indeed, why not nationalize every profitable industry?

It might be useful to attempt an understanding of why Blumenthal, a Greenwich millionaire many times over, supports a scheme of government that will run insurance companies out of Connecticut and the nation.

Theories abound. One holds that Blumenthal has never had a handle on how the private marketplace really works.

After marrying the daughter of a New York real-estate mogul – Blumenthal’s in-laws own the Empire State Building, in addition to other prime holdings – the Harvard/Yale graduate went directly into Connecticut politics. As attorney general of the state for two decades, Blumenthal used businesses as a foil to ingratiate himself with the voting public and a fawning state media, both equally indispensable to his acquisition of political position and power. Blumenthal is now schmoozing with Sanders, so the theory goes, to further his own political ambitions. Even Bill and Hillary Clinton, long-time friends of Blumenthal, had great difficulty keeping down Sanders’s elixir.

The second theory goes like this: The National Democrat Party is playing with the economic DNA of the United States – only for political (read: campaign) reasons. Seizing the profits generated by a still relatively free marketplace in the United States, encumbering it with unsupportable taxes and regulations, may not advance the general good, but it certainly helps to improve the lot of political destructors-elect. Socialist Maduros of the world live in opulent splendor, while the people who struggle under Maduro’s socialist rule in Venezuela, once a pearl of Latin America, are forced to search through garbage bins for their lunch.

In Blumenthal’s case, both theories may be true -- not that truth has anything to do with the daily operations of political shysters.

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn.-based columnist. Editor’s note: George Orwell was a democratic socialist.

'That's what we do' in Vermont

“For much of America, the all-American values depicted in Norman Rockwell's classic illustrations are idealistic. For those of us from Vermont, they're realistic. That's what we do’’

— U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.)

In Newfane, Vt.

Josh Hoxie: Past time for a sociopathic generation to leave the political scene

Baby Boomers watching TV in the late '50s.

Via OtherWords.org

Historians won’t look fondly on 2017.

The news cycle was dominated by sexual assault, widespread anxiety, the unedited musings of a mentally unstable president, rising economic inequality, and an opioid epidemic. And in case you forgot, the planet is still on track to boil.

In short, things were bad.

This year, it’s time to transition from despair to action.

We saw the beginnings of this transition as hundreds of political newcomers came out of the woodwork to run for state and local office last year. And thousands more started the process to run in 2018 and beyond.

Democracy isn’t a spectator sport, and it’s good to see a younger generation more politically engaged than their parents. Unfortunately, the younger folks will have many messes to clean up left by their elders.

Bruce Cannon Gibney goes so far as to depict Baby Boomers, those born between 1946 and 1964, as sociopaths in his book, A Generation of Sociopaths: How The Baby Boomers Betrayed America.

Not all of them, of course.

Gibney limits his analysis to mostly white, native-born, powerful Baby Boomers — the ones in position to make decisions on behalf of everyone else. At each critical juncture, Gibney argues, these Boomers looked after themselves at the expense of everyone else.

Thanks. For. Nothing.

We saw this play out most recently in the tax cut package just passed by Congress. Regardless of the bluster coming from the White House, this bill was nothing more than a wealth grab by the already ultra-wealthy. Over 80 percent of the tax cuts go to the top 1 percent.

Poll after poll showed the majority of Americans understood this. Yet congressional Republicans chose to work on behalf of their donors instead of their constituents.

We see this playing out again as they threaten the Medicare and Social Security of future beneficiaries. That’s millennials they’re targeting, not Baby Boomers. That’s not a coincidence.

In case you couldn’t tell by the abundance of wrinkles and white hair on C-Span, the people making the decisions in Washington are not young. The average age in the Senate is 61, eight years older than 1981. More than a quarter are over 70. The last four presidents have all been Baby Boomers. They oversaw the greatest expansion in economic inequality in modern history.

Young people are inheriting an economy in which it’s all together common to start adulthood tens of thousands of dollars in debt, thanks to a higher education system rooted in exploitation. Meanwhile wages are generally stagnant, and the federal minimum wage falls below the cost of living of every major city in the country.

Young people are rightfully outraged at this inequality and are ready to take bold action to address it. Or, as legendary Republican pollster Frank Luntz put it, millennials are “terrifyingly liberal.”

Naturally, age isn’t everything. Paul Ryan, born after the Baby Boomers, wants to completely destroy the social-safety net. Bernie Sanders, technically too old to be considered a Boomer, might be the biggest advocate for young people in Washington.

Bernie also has massive support among youths. More Millennials cast a ballot for him in the 2016 presidential primary than both Clinton and Trump combined. Unfortunately, Sanders is the exception, not the rule, among his cohort in Washington.

Young people are ready, willing, and able to take a leadership role in healing our deeply broken society and environment. It’s time for the “olds” in Washington — either of age or of ideology — to make way for the rising generation.

Josh Hoxie directs the Project on Taxation and Opportunity at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Looking for indigenous affirmation

Native American tribes in southern New England as of about 1600.

-- Map by Nikater, adapted to English by Hydrargyrum

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

There was a brief uproar last week when Donald Trump, speaking at a ceremony at the White House to honor Navajo “code talkers,’’ who were very helpful in the U.S. military in World War II, made a joke about Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s claim to have some Native American ancestry. He yet again called her “Pocahontas.’’ Like most of this con man’s jokes, it was stupid and nasty. Still, I, too, doubt if the Massachusetts senator has any Native American blood, though she has suggested she does. How about having your DNA tested, senator? That would clear this up.

(Some of my relatives have insisted that we have Cape Cod Wampanoag blood. Another romantic family myth. Or looking for some casino money….)

More troubling was that on the wall behind Trump and the honorees was a big portrait of the horrible President Andrew Jackson, the thug who helped force thousands of Indians from their homelands in the Southeast to west of the Mississippi. Many thousands died on this “Trail of Tears.’’

Trump has frequently expressed his admiration for Jackson, and indeed had that portrait hung there.

xxx

Speaking of Warren, I wonder if the Democrats will be crazy enough to nominate her or Bernie Sanders for president in 2020. The Dems should be in a strong position to win back the White House in three years because of Trump’s corruption and incompetence and what’s likely to be a recession in the next couple of years. But the stridency of Sanders and Warren is unlikely to be a big hit in the next campaign. And they’d both be too old. By that point, I think, Americans will be looking for a calm and only slightly left-of-center leader, preferably someone who had been a successful governor. (But watch Sen. Kirsten Gillebrand, of New York....)

Or it may be a name that few Americans would recognize now.

Chuck Collins: Best wishes to the most indebted class

Congratulations, college graduates! As you enter the next phase of life, you and your parents should be proud of your achievements.

But, I’m sorry to say, they’ve come at a price: The system is trying to squeeze you harder than any previous generation.

Many Baby Boomers, perhaps including your parents, benefited from a time when higher education was seen as a shared social responsibility. Between 1945 and 1975, tens of millions of them graduated from college with little or no debt.

But now, tens of millions of you are graduating with astounding levels of debt.

This year, seven in 10 graduating seniors borrowed for their educations. Their average debt is now over $37,000 — the highest figure for any class ever.

Already, some 43 percent of borrowers — together owing $200 billion — have either stopped making payments or are behind on their student loans. Millions are in default.

This debt casts a long shadow on the finances of graduates. During the last quarter of 2015 alone, the Education Department moved to garnish $176 million in wages.

There’s no economic benefit to this system whatsoever. Indebted students delay starting families and buying houses, experience compounding economic distress, and are less inclined to take entrepreneurial risks.

One driver of the change from your parents’ generation has been tax cuts for the wealthy, which have led to cuts in higher education budgets. Forty-seven states now spend less per student on higher education than they did before the 2008 economic recession.

In effect, we’re shifting tax obligations away from multi-millionaires and onto states and middle-income taxpayers. And that’s led colleges to rely on higher tuition costs and fees.

In 2005, for instance, Congress stopped sharing revenue from the estate tax — a levy on inherited wealth exclusively paid by multimillion-dollar estates — with the states. Most state legislatures failed to replace it at the state level, costing them billions in revenue over the last decade.

In fact, the 32 states that let their estate taxes expire are foregoing between $3 to $6 billion a year, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates. The resulting tax benefits have gone entirely to multi-millionaires and billionaires — and contributed to tuition increases.

For example, California used to raise almost $1 billion a year in revenue from its state-level estate tax. Now that figure is down to zero. And since 2008, average tuition has increased over $3,500 at four-year public colleges and universities in the state.

Florida, meanwhile, lost $700 million a year — and raised tuition nearly $2,500. Michigan lost $155 million a year and hiked average tuition $2,200.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Washington State went the opposite route.

Washington taxes big estates and dedicates the $150 million it raises each year to an education legacy trust account, which supports K-12 education and the state’s community college system. Other states should follow this model, and students and parents should take the lead in demanding it.

Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders said at a Philadelphia town hall meeting that there’s one thing he’s 100 percent certain about.

If millions of young people stood up and said they’re “sick and tired of leaving college $30,000, $50,000, $70,000 in debt, that they want public colleges and universities tuition-free,” he predicted, “that is exactly what would happen.”

Sanders is right: Imagine a political movement made up of the 40 million households that currently hold $1.2 trillion in debt.

If we stood up and pressed for policies to eliminate millionaire tax breaks and dedicate the revenue to debt-free education, it would change the face of America.

Graduates, let’s get to work.

Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Llewellyn Smith: Hedrick Smith a torchbearer for beaten-down middle class

The middle class has been taking a shellacking for years. It began in the 1970s, when the business and political elites separated from the people and it has been accelerating ever since, according to Hedrick Smith, a former Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times reporter and editor, an Emmy award-winning PBS producer and correspondent, and a bestselling author. In short, an establishment figure.

Add to Smith’s establishment credentials schooling at Choate, the private boarding school, a stint at Oxford, and you have the picture of someone with the credentials to join the elite of his choosing. Instead Smith is a one-man think tank, a persuasive voice against the manipulation of the public institutions, such as Congress, for money and power.

But Smith is not a polemicist. He uses the reporter's tools, honed over decades in Moscow and Washington and on big stories, such as the civil-rights movement and the fall of the Soviet Union, to make his points against the assault on the middle class.

It all began with Smith's looking into what was happening to American manufacturing, which led to his explosive 2012 book, Who Stole the American Dream? Encouraged by the book's success, he created a Web site,reclaimtheamericandream.org, which now has a substantial following. In the past three years, he has lectured at over 50 universities and other platforms on his big issue: the abandonment of the middle class by corporate America and its corrupted political allies.

Smith documents the end of the implicit contract with workers, where they shared in corporate growth and stability. He outlines how money has vanquished the political voice of the middle class.

Instead, according to Smith, corporations have knelt before the false god of “shareholder value.” This has resulted in the flight of corporate headquarters to tax-friendlier climes, jobs to cheap labor, and a managerial elite indifferent to those who built the companies they manage.

In Smith’s well-researched world it is not only the corporations that have abandoned the workers, but the political establishment is also guilty, bowing to lobbyists and fixing elections through redistricting. Two big villains here: money in politics and gerrymandering electoral districts.

The result is a democracy in name only that serves the powerful and perpetuates the power of those who have stolen the system from the voters.

Smith cites the dismal situation in North Carolina, where districts have been drawn ostensibly to ensure black representation in Congress, but also to ensure Republican domination of all the surrounding districts. The two districts that illustrate the mischief are called “the Octopus” and “the Serpent” because of the way they are drawn to identify the voter preference of the inhabitants.

The rise of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump are testament to the broken system, says Smith. They are symbolic of the rising up of the middle class against the predations of the elites.

But Smith is hopeful because, he says, the states have taken up arms against the Washington and Wall Street elites. People should “look at the maps,” he says, “They will be surprised to find out that 25 states are engaged in a battle against partisan gerrymandering, or that 700 cities and communities plus 16 states are on record in favor of rolling back ‘Citizens United’ and restoring the power of Congress to regulate campaign funding.”

Smith sees the middle class reclaiming America: a great social revolution that again unites the government with governed, the creators of wealth with the managers of the wealth. Smith is no Man of La Mancha, tilting at windmills, but a torchbearer for a revolution that is underway and overdue.

“My thought is that more people would be emboldened to engage in grassroots civic action if they could just see what other people have already achieved,” he told me.

Smith’s Web site has drawn 82,000 visitors in the past year, and Facebook posts have reached 2.45 million, he says.

Smith cautioned me to write about the Web site and cause and not the man. But the man is unavoidable, and unique. He has as much energy as he had when I first met him in passing in a corridor at the National Press Club in Washington decades ago. At 82, Smith still plays tennis, skis, hikes, swims and dances with his wife, Susan, whom he describes as a “gorgeous dancer.”

At 6 feet 2 1/2 inches, Smith is an imposing figure at the lectern, but his delivery is gentle and collegiate: a reporter astounded and pleased with what he has found in the course of his investigation of the American body politic.

Llewellyn King is host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He is a long-time publisher, columnist and internationalist business consultant. This piece first ran on Inside Sources.

Robert Whitcomb: Mr. Brooks finally discovers that the natives are restless

In an April 29 column by The New York Times’s David Brooks headlined “If Not Trump, What?’’ he writes that to understand Donald Trump’s GOP popularity (and by implication Bernie Sanders’s among Millennials):

“{I]t’s necessary to go out into the pain. I was surprised by Trump’s success because I’ve slipped into a bad pattern, spending large chunks of my life in the bourgeois strata — in professional circles with people with similar status and demographics to my own. It takes an act of will to rip yourself out of that and go where you feel least comfortable….’’

“….Up until now, America’s story has been some version of the rags-to-riches story, the lone individual who rises from the bottom through pluck and work. But that story isn’t working for people anymore, especially for people who think the system is rigged.’’

How little effort much of the elite have made to know the plus-90 percent of the nation who aren’t. You’d think that big-time journalists would try to talk more to “everyday Americans,’ at least for show. But media celebs such as Mr. Brooks are addicted to the money, privilege and ego-gratification that go with spending most of their time with the rich and/or powerful. Meanwhile, many business/economics journalists have been fired to help maintain media outlets’ profit margins. So rigorous, data-driven coverage of socio-economic changes has declined in the media that American most look at in favor of, well, nonstop coverage of Mr. Trump’s latest insults. (I’m a former business editor.)

Mr. Brooks, et al., now seem to fear that massive social unrest is coming unless members ofthe “middle class’’ think that they will get a better deal. (Of course, many low- and middle-income people could help their situations by, for example, avoiding having kids out of wedlock and other disorderly behavior linked to poverty. They could also vote.)

The nub of the problem:

Government data show that American economic productivity in 1945 -1973 rose 96 percent and inflation-adjusted pay 94 percent; in 1973-2014 productivity grew 72.2 percent and inflation-adjusted pay 9.2 percent, with almost all of the growth in 1995-2002.

This suggests that the folks owning and/or running companies have become much less willing to share. At the same time, tax laws remain very skewed in favor of investment income over earned income. This keeps reinforcing a plutocracy based on inherited capital and privilege. The Sunday New York Times weddings section displays this crowd in all its glory.

Meanwhile, the elite’s disinclination to share has slowed economic growth by constraining most Americans’ purchasing power.

The very rich have increasingly sequestered themselves from the poor and the middle class through, among other things, jet travel, globalization, the Internet and gated communities. Thus they’re less likely to see and be embarrassed by extreme divergences of wealth. Ever more large local enterprises are owned by far-away companies and/or individuals rather than by people in the communities where the companies operate. The local employees are mere numbers on a screen rather than people whom senior executives and major shareholders might awkwardly encounter on the street.

In some of the burgs where my family have lived over the past century, such as Brockton, Mass., when it was a shoe-making capital, and Duluth, Minn., an iron-ore and grain shipping port, my relatives who were executives, factory managers and the like would encounter a wide range of the population daily, from rich to poor. Now, the descendants of these folks who have not yet drunk away the old money made in these places tend to spend six months and a day enjoying tax avoidance in Florida , and those who own and/or run largeenterprises with operations in places like Duluth and Brockton may never visit them at all.

Out of sight, out of mind.

But now there’s the glint of pitchforks in the sun. It’s too bad that the leading spokesmen for the new “populism’’ are con man Donald Trump (see: www.trumpthemovie.com) and a naïf like Bernie Sanders, who doesn’t understand the need to always encourage entrepreneurialism to raise living standards. As for the Clintons, all too often they act like establishment grifters.

Anyway, we need capitalism, but adjustments are long overdue.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com), a former Providence Journal editorial page editor, a former International Herald Tribune finance editor and a former Wall Street Journal editor, oversees New England Diary and is a partner at Cambridge Management Group and president of Guard Dog Media, based in Boston.

Isaiah J. Poole: Give 'tax and spend' a chance

via otherwords.org

This time of year, a whole lot of Americans are feeling taxed enough already.

But the astonishing momentum of Bernie Sanders’s presidential candidacy reveals something else: Millions of taxpayers are willing to entertain the idea that some of us aren’t taxed enough, and that it’s hurting the rest of us.

Sanders has propelled his race against Hillary Clinton on a platform that would ramp up government investment — in infrastructure, education, health care, research and social services — while boosting taxes on the wealthiest Americans and big business to cover the cost.

Clinton’s own vision is less ambitious, but it’s also a far cry from “the era of big government is over” days of her husband’s administration.

The old conservative epithet against “tax-and-spend liberals” hasn’t completely lost its sting, says Jacob Hacker, a political-science professor at Yale University who pushed the idea of a public option for health insurance during the Affordable Care Act debate. But “we are moving toward the point where we can have an active discussion” about why “you need an activist government to secure prosperity.”

Hacker’s latest book, with Paul Pierson of the University of California at Berkeley, is American Amnesia: How the War on Government Led Us to Forget What Made America Prosper.

Hacker and Pierson argue that it was “the strong thumb” of a largely progressive-oriented government, in tandem with “the nimble fingers of the market,” that created the broad prosperity of the post-World War II era. Conservative ideologues and corporate leaders then severed that partnership.

Anti-government activism replaced the virtuous cycle of shared prosperity that existed into the 1970s with a new cycle that’s reached its depths in today’s radical Republican-run Congress: Make government unworkable. Attack government as unworkable. Win over angry voters. Repeat.

But in today’s mad politics, growing numbers of voters seem to have gotten wise to the routine and how it’s been rigged against them. Some are gravitating toward Donald Trump, as Hacker puts it, out of “the need to put a strong man who you know is not with the program in Washington in charge.”

Sanders has the opposite vision. He’s looking to spark a people-powered reordering of what government can do, with the biggest wealth-holders paying the share of taxes that they did when America’s thriving middle class and thriving corporate sector were, together, the envy of the world.

That vision is embodied in "The People's Budget.'' a document produced by the Congressional Progressive Caucus as an alternative to the House Republican budget.

It’s based on the premise that America can break out of its slow-growth economic malaise through a $1 trillion infrastructure spending plan that would create more than 3 million jobs, increased spending on green-energy research and development, and universal access to quality education from preschool through college.

“There are two messages that come out of the progressive budget,” Hacker said. One is that “we can actually increase investment if we don’t cut taxes further on the wealthy.” The other is that “if we got tougher with the modern robber barons in the healthcare and finance and energy industries, we could actually achieve substantial savings without cutting necessary spending.”

Unfortunately, The People’s Budget won’t get close to a majority vote in Congress — and that’s if it gets a vote at all in the dysfunctional Republican House.

Yet together with the debate provoked by the Sanders campaign, Hacker says, it shows that now “we have a little bit more of an opening for the kind of conversation we should’ve had 20 or 30 years ago, when we were trashing government and abandoning all of these long-term investments that are essential to our prosperity.”

Isaiah J. Poole is the online communications director at Campaign for America’s Future (OurFuture.org).

Robert Whitcomb: The gig economy

I’m old and lucky enough that most of my working life took place when large U.S. enterprises usually made long-term commitments, albeit often rather vague, to their competent workers. If a recession hit, senior executives would grit their teeth and try to hang on to their employees. Back when I was a business editor at The Wall Street Journal, the International Herald Tribune and elsewhere, Fortune 500 senior executives’ commitment to their fellow employees often impressed me. Not much anymore!

There was something like two-way loyalty, and the top people often showed a certain sensitivity about public perceptions of their compensation.

Now the idea is to maximize short-term profit and stock price and thus senior execs’ and board members’ compensation above all else. I have seen that in some sectors where managements that used to be satisfied with 15 percent profit margins raised them to over 30 percent. And CEOs now make on average over 300 times the average pay of their employees, compared to 20 times in 1965!

Thus many companies refuse to spend money on long-term investments, such as employee training: While such outlays strengthen companies in the long haul, they cut into short-term net income. So train yourself – you may well be laid off next month anyway.

Then there’s the rise of the “gig economy,’’ in which “on-call’’ workers, “permatemp workers,’’ “independent contractors’’ and people employed by such contract firms as Manpower comprise an ever larger share of the workforce.

The Wall Street Journal reports that these days 17 percent of women and 15 percent of men have such “alternative employment.’’ Such jobs are up by more than half from 2005. (See ‘’’Gig’ Economy Spreads Broadly,’’ WSJ March 26-27).

These positions, with their very unpredictable hours, pay lower wages than regular jobs and offer few if any fringe benefits. They are spreading rapidly across more sectors, such as law and healthcare, pulled by computerization and globalization. They have long been particularly common in higher education, which depends on low-paid adjunct teachers to offset the cost of almost-impossible-to-fire tenured professors, with their high salaries and big benefits.

Employers obviously need flexibility to adjust their staffing levels. But when they reduce the ranks of their full-time employees beyond a certain point to keep short-term profit margins and senior executive pay sky high, they risk undermining the viability of their enterprises by destroying the institutional memory and employee morale and loyalty needed formost enterprises’ long-term success.

Short-termism usually triumphs. CEOs don’t expect to have their jobs very long; thus they want to accelerate their compensation.

Meanwhile, the economy as a whole tends to stay in a low-growth pattern as the purchasing power of most people shrinks and national wealth is increasingly concentrated in a tiny group whose members can perpetuate their (and their children’s) power with the aid of cash (and later, lobbying and other jobs) for politicians in return for favorable policies.

We’ll see a revival of private-sector unionization as more workers see that as the only way to obtain a modicum of economic security. We’ll also see an increasing number of economically insecure Americans following the siren song of such con men as Donald Trump and such presumably sincere but wrong-headed reformers as Bernie Sanders who don’t understand the need to encourage the “animal spirits’’ of entrepreneurism; Mr. Sanders has never had a job in business. There are reasonably centrist policies that can make things better, such as adjustments in the tax code and labor regulations.

None of this is to say that “contingent’’ and/or freelance employment can’t work well for some people. I myself have enjoyed some of its flexibility as a partner in a couple of small businesses. But you can’t build a strong economy on it.

xxx

Post-Brussels, President Obama and some other sensitive souls continue to avoid saying “Islamic’’ before “terrorism’’. They’re being intellectually dishonest. Islam (mostly its Sunni side) has big problems, the worst being that too many of its emotionally needyfollowers adhere to the 7th Century barbarism and supremacism in some of its scripture. Islam needs a reformation.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com) is a Providence-based editor and writer and overseer of this site.

Llewellyn King: America's great gale of 2016

If you accept that seminal means an event or moment after which things will never be the same again, then we are living through a seminal year.

In matters big and small, change is in the wind.

This wind has been blowing through presidential primary and caucus states and is defining the 2016 presidential election. Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders are not so much the leaders of this time of change, but rather the products.

The product is something hard to pin down, but it is there nonetheless — a sense that it is time to turn the page, to read the next chapter; a yearning for something fresh.

The Millennials, hunched over their cell phones, are looking for the future in their small screens. The rest of us are looking for it in new leaders, new lifestyles; and new thinking, sometimes about old ideas.

Societies go through periods when they feel the need to change up things. But they want a sped-up evolution rather than a full-fledged revolution. This is such a time.

Change is everywhere from the bold, new things television is doing — frontal nudity, gay coupling and interracial love — to the kind of car we favor.

While we grapple with change and yearn for the new, we are surprisingly open-minded. American values appear to be undergoing a recalibration: We are getting more socially tolerant. Social conservatives are a diminished force.

Young people do not have the same commitment that their parents had to conventional employment, to be defined by where they work. This leads to a world where people are less concerned with appearances, and all that goes with appearances. The business suit and its essential accoutrement, the necktie, are on the way out – and in much of the country, they are now curiously out of date. Apartments are being favored over houses because of new social values.

My generation experienced the hopeful 1940s (just the tail end), the smug 1950s, the turbulent 1960s, the oil-shocked 1970s, and the computer-excited 1980s, which continued unabated until the dot-com bubble burst at the turn of the century – but re-inflated with new developments in Internet products like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.

In recent times, the only new American billionaire outside of the Internet was Hamdi Ulukaya, who popularized Greek yogurt in country hungry for yogurt choices. That is a dumbfounding fact. It means that it will be harder to get investment in old-line businesses and start-ups. The smart money has become myopically obsessed with the cyberworld.

If you were to go to Wall Street today to raise money for a new nuclear reactor that put all doubts of the past to rest and offered income for 100 years — there are such machines on the drawing board – you would find it hard to raise money; easier for a new Internet messaging system. This when there is no shortage of Internet messages (too many, I cry each morning). We are leery of the hard and enamored of the soft.

We sense that the education system is not doing its job; that it is broken and needs fixing. But how, we are not sure. We are sure, though, that we are going to change it.

We sense that we had the dynamic wrong in foreign affairs; that change at home, like toppling a generation of political leadership, is desirable, while toppling leaders abroad is a fraught undertaking, as with Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi and Bashar al-Assad.

We feel less good about the wealthy, and we are less sure that there are secure places for us in the future. We watch cooking shows and order in pizza. We gave up smoking and started jogging. But we are, so to speak, deaf to the damage we are doing to our ears with incessant music piped to them by earbuds.

We are more nationalistic and less confident at the same time. We treasure our values more, and wonder about their long-term durability.

The largest contradiction that can easily be inspected is in the themes of Trump and Sanders: Trump has rehabilitated a kind of racism aimed at immigrants, while Sanders has made the taboo word “socialism” acceptable in political dialogue.

The desire for change has moved from a slight wish to a hard desire for a new alignment. It is everywhere, from what we eat to how we feel about the climate. But we do not agree on this new alignment, hence the huge gulf between Sanders followers and Trump adherents.

Llewellyn King is a long-time publisher, international business consultant and columnist (and friend of the overseer of New England Diary). This piece first ran inInsideSources.

David Warsh: Trying to make sense of America's age of disaggregation

"I am as eager as the next guy to make sense of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, but I do not expect to work my way through to useful opinions by following the primary and caucus returns."

Seeking distance from the dispiriting political news, I spent the best hours of last week reading various chapters of four books by Princeton historian Daniel T. Rodgers. I am as eager as the next guy to make sense of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, but I do not expect to work my way through to useful opinions by following the primary and caucus returns. So I turned to the work of a scholar who has spent his career writing about the evolution of the political culture of modern capitalism in the U.S. over the last 150 years.

I first read Rodgers a few years ago after an old friend recommended Age of Fracture, which had won a Bancroft Prize in 2012. I was struck by how attentive the historian had been to various developments in economics in the 1960s and ’70s I knew something about: the influence of deregulators such as Ronald Coase and Alfred Kahn, macroeconomists Milton Friedman and Robert Lucas, lowbrow supply-siders, highbrow game theorists, legal educator Henry Manne.

I know much less about the other realms Rodgers reconnoitered in the book in order to elaborate his central metaphor – international relations, class, race, gender, community, narrative. But I know that his fundamental diagnosis rings true. Life today is more specialized, more highly differentiated, and, yes, somehow thinner than in the past.

"Conceptions of human nature that in the post-World War II era had been thick with context, social circumstance, institutions and history gave way to conceptions of human nature that stressed choice, agency, performance and desire. Strong metaphors of society were supplanted by weaker ones… Imagined collectivities shrank; notions of structure and power thinned out. Viewed by its acts of mind the last quarter of the century, was an era of disaggregation, a great age of fracture.''

Over the next year I skimmed Rodgers’s three previous books. They turned out to offer a fairly seamless narrative of, not so much economic history, but arguments about economic history, over the course of a century and half. Rodgers was born in 1942, graduated from Brown University in 1965 and got his Ph.D. from Yale in 1973, taught at the University of Wisconsin until 1980, when he moved to Princeton University, where today he is the Henry Charles Lea Professor of History, emeritus

That first book, The Work Ethic in Industrial America: 1850-1920, traced American attitudes towards work, leisure and success, from relatively small-scale workshops before the Civil War to highly mechanized factories at the beginning of the industrial age. The second, Contested Truths: Keywords in American Politics since Independence, identified a handful of ostensibly technical terms – “utility,” “natural rights,” “the people,” “government,” “the state,” and “interests” – and examined their use in arguments, especially as the confident tradition he describes as “liberal” gave way to a rediscovery, both academic and popular, of “republicanism” in the Reagan years.

The third work, Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age, is a highly original reconstruction of various ways “progressivism” was understood in the first half of the twentieth century, in Europe and the United States: corporate rationalization, city planning, public housing, worker safety, social insurance, municipal utilities, cooperative farming, wartime solidarity, and emergency improvisation in the Great Depression. (A research assistant was Joshua Micah Marshall, who went on to found the influential online news site Talking Points Memo.)

Age of Fracture is the fourth.

It’s a rich vein. I plan to mine all four over the next few months, making a Sunday item, when and if I can. One needs something to discipline mood swings during the rest of the campaign, and I’ve decided that, for me, this is it.

Today I’ll offer a small but concrete example of what Rodgers calls “ideas in motion across an age,” or, in this case, many ages. American exceptionalism is a persistent theme with him: the free-floating idea that, as “the first new nation” and “the last best hope of democracy,” the United States has a mission to transform the world and little to learn from the rest of it. Is that the note that Trump so single-mindedly and simple-mindedly strikes when he promises to “make American great again”? It helps me to think so.