But it usually doesn't usually last long

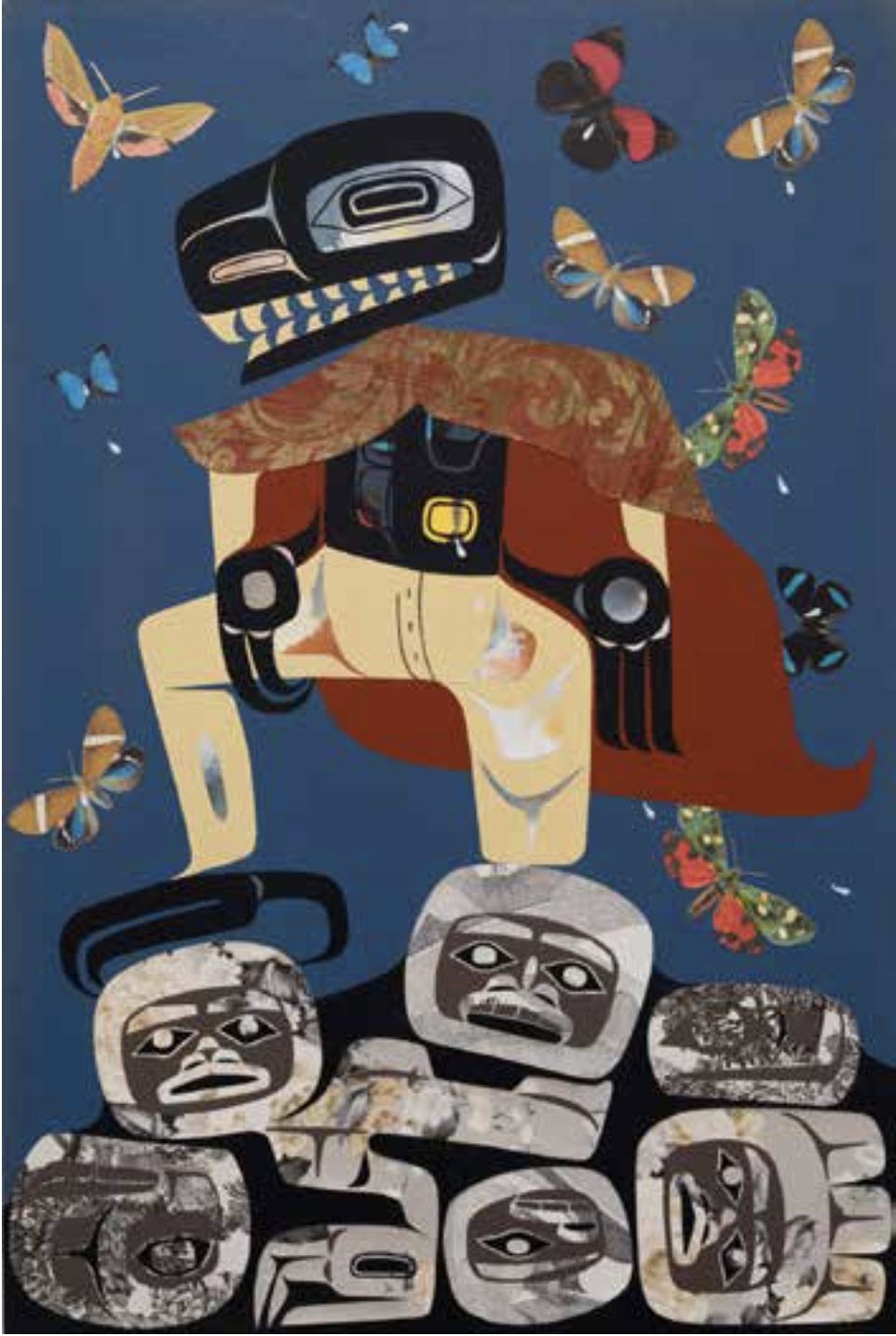

“Infatuation” (acrylic, wallpaper on canvas), by Allison Bremner, at Bates College (Lewiston, Maine)) Museum of Art.

— Image courtesy of artist, who is of Alaskan Native American background.

Hathorn Hall, at Bates College

— Photo by Odwallah

Textile mills in Lewiston along the Androscoggin River about 1910. The city became a major industrial center in the mid-19th Century, first with sawmills, then with textiles. Money from the latter helped found Bates College, in 1864. Many of the workers were of French-Canadian background, and French used to be widely spoken in the city.

Sadly, Maine’s second largest city, after Portland, became nationally know for Robert Card’s mass shooting there on Oct. 25. that killed 18 people in the normally peaceful place.

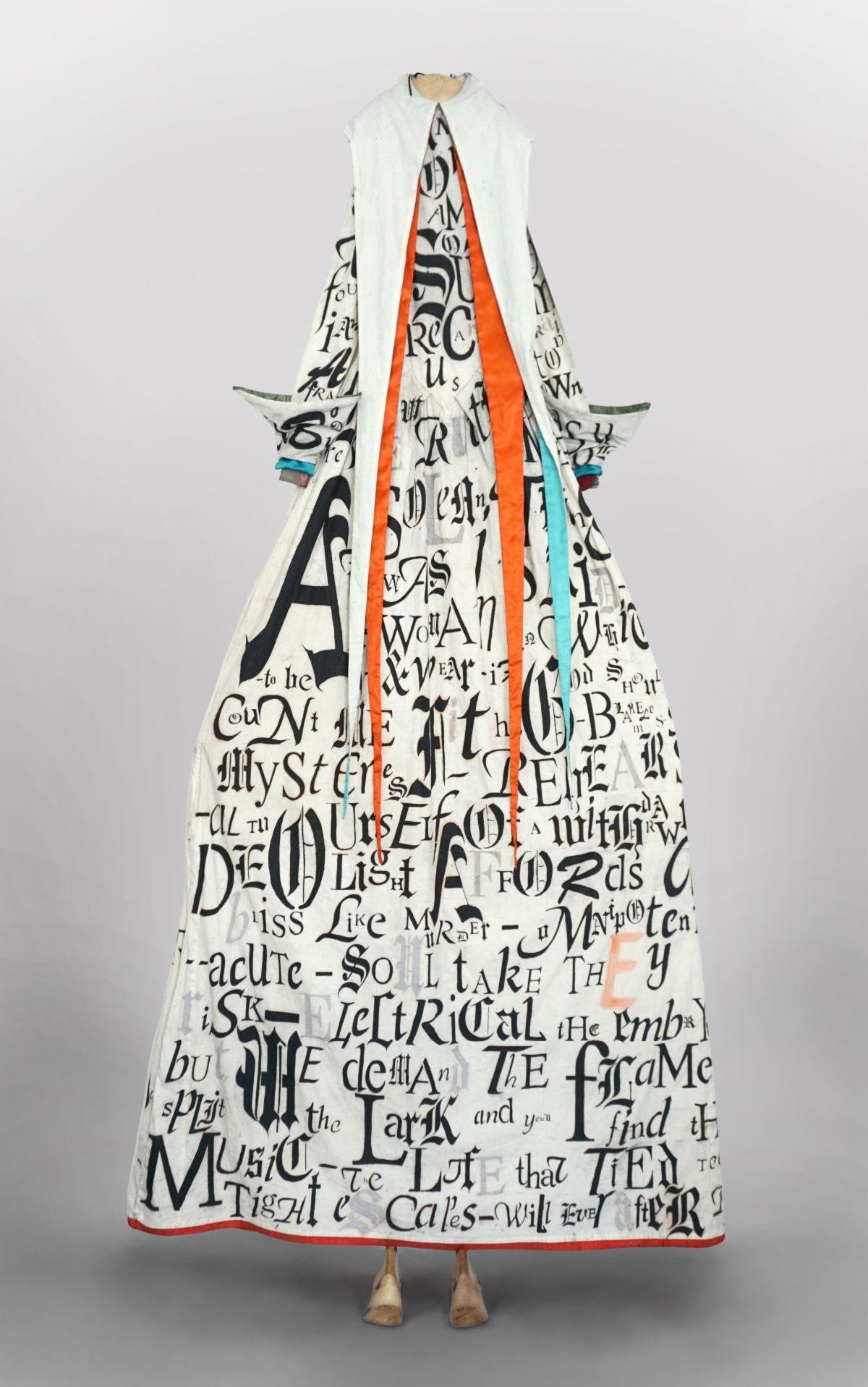

Wearing word art

“Omnipotence Enough (Emily Dickinson)’’ (oil paint on fabric, wooden yoke and shoe lasts), by Lesley Dill, in her show “Lesley Dill: Wilderness, Light Sizzles Around Me,’’ at the Bates College Museum of Art, Lewiston, Maine, Jan. 28-March 26.

Among other things, Ms. Dill explores "the voices and personas of the American past,’’ including "inspiration in the poetry, prose, and declarations of early New England figures….” such as the great poet Dickinson (1830-1886).

Taking in city life

“City Hall Picket Line” (pencil and gouache), by Joseph Delaney (1936), in the show “Joseph Delaney: Taking Notice,’’ at the Bates College Museum of Art, Lewiston, Maine.

The museum says:

“African American artist Joseph Delaney (1904-1991) took notice of life around him. He was drawn to figurative art and lively scenes of urban life, and his work focused primarily on the people and environment of New York City, the place where he lived much of his adult life. Delaney was an acute observer of people and their activities, and he recorded them, sometimes in paintings, but more often in works on paper—drawings, pen and ink washes, watercolors, and in the notebooks that he carried and drew in everywhere he went.

“Delaney, who created thousands of works in a life spanning every decade of the twentieth century, was recognized but never celebrated during his life. Since that time, institutions and collectors have increasingly taken notice of his work, which is now in collections including the Art Institute of Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“Taking Notice’’ is the first exhibition in New England devoted to the work of Joseph Delaney. Drawn primarily from the extensive holdings of the University of Tennessee and complemented with several works from private collections and the Bates Museum of Art, it features paintings and many works on paper, representing a breadth of subjects about life in the city that fascinated Delaney during his prolific life, including parades and protests, figure drawings and portraits, and monuments and parks in Manhattan.’’

Unknown friends

“I take a seat in the third row

and catch the eulogies. It’s sweet

to see old friends, some I don’t know.’’

— From “At My Funeral,’’ by Willis Barnstone, a native of Lewiston, Maine, now living in California

Lewiston mills on the Androscoggin River circa 1910 during the city’s mill town heyday.

In Lewiston, view from the steps of Bates College’s Hathorn Hall looking toward quad and Lindholm House, the admissions office

Caitrin Lynch: 30 years later, of memory and forgetting

Bates College's oldest academic building, Hathorn Hall , was built in 1856 by Boston architect Gridley J. F. Bryant.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

With all the discussion about what best prepares students for work and life, two candidates are interdisciplinary thinking and international awareness. This past summer, exactly 30 years after I graduated from college, my favorite professor at Bates College (in Lewiston, Maine) retired, which led me to think about my own early experiences with these ways of thinking and being.

To prepare for Steve Kemper’s retirement party, I dug through a box of college notebooks and papers that I had moved unopened from one apartment and city to the next for the past three decades. I found a pastel pink exam book, with my name in pencil on the cover. Inside, I saw my handwriting, no different than today’s. As I began to read, I didn’t remember writing or knowing any of what was on these pages. My 19-year-old self possessed deep specific knowledge that is long gone from my memory, 30 years on. But I did recognize that this exam was for a course Steve taught my sophomore year, on culture and politics in South Asia.

Steve’s name doesn’t show up anywhere, but his handwriting is unmistakable. A cursive like no other: loopy, ornate, enthusiastic, and generous, with tails on letters like x, p, and y flowing down with a flourish. Steve had written comments in the margins, including a correction when I wrote “bride price” instead of “dowry.”

I learned from my exam that back when I was only 19 years old, I knew a lot about what might be considered pretty esoteric things. Before this class, I knew nothing about South Asia. I enrolled by accident, thinking “South Asia” referred to what I now know is Southeast Asia. My father is a Vietnam War vet, and I wanted to learn more about Vietnam. Instead, on the first day of class, Steve had pulled down a map from a roller above the chalkboard and drew me quickly into learning about India and its neighboring countries—including Sri Lanka, where I eventually spent many years and learned two of the languages spoken there.

Memories can be triggered by a whiff of an odor, a snippet of a song, or a bit of food: events, experiences, and emotions long-ago tucked away spring up at a resonant prompt. Holding the exam book in my hand, I suddenly remembered working in the college library; studying for hours for Steve’s tests; re-reading books, articles and lecture notes; taking new notes and writing practice responses to questions he had provided in advance.

When I remembered the library study sessions, I had an epiphany. There was something about the esoteric nature of the exam topics, and my absence of memory of the details of the materials but clear memory of studying for the test, that led me to really understand—just in time for my 30th reunion—what I learned in college.

Back then, I was focused on the details of the societies Steve instructed me about. I am sure I didn’t appreciate what was at stake, why this kind of learning matters so much. I now see that Steve helped me to have a genuine interest in people unlike me, and to understand the necessity and value of the hard work of reading, researching, interviewing, seeing, feeling, talking, listening: all in the interest of making sense of how we live in the world, what matters most for people and why. In learning about the efforts toward justice by Mahatma Gandhi or by unionized workers in Calcutta, or in learning about menstruation practices among Tamils in Sri Lanka, I developed a lifelong attention to the values, customs, aspirations and struggles of people near to and far from my daily life. Steve taught me that this kind of learning and understanding is hard but essential work.

Nowadays, I use that conviction to learn and understand, and to make sense of everyday conversations, first-hand experiences and news items—say, about the Indian government’s revocation of special status for Indian-controlled Kashmir, debates about the separation of migrant families at the US-Mexican border, or the causes and impacts of last spring’s Easter Sunday bombings in my beloved Sri Lanka. From Steve, I learned how to identify what I know and what I don’t know. I learned why it matters that I spend time to learn, humbly and with deep curiosity and respect.

Today I’m an anthropology professor, like Steve. I teach my students how to understand and respect people unlike themselves, and I teach them how this is the road to creating experiences of equity and justice. Steve has retired from 45 years of transformative education. And yet, his work is not done. During this moment in American life where misunderstanding across communities reigns, educators of my generation and the next must step up and do more of this work.

Caitrin Lynch is a cultural anthropologist at Olin College of Engineering, in Needham, Mass.

Tags: anthropologist, Bates College, Olin College of Engineering

Leave a Reply

Your Name*

Your E-Mail*

Got a website?

Dan Wallace: Making things better down in the boiler room

From the New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

DANBURY, Conn.

For many institutions in New England, the 2020 deadline to hit objectives for the Presidents' Climate Leadership Commitments that once seemed far away are now right around the corner. These ambitious plans were entered into in 2007 with the American College & University Presidents' Climate Commitment—in some cases, by now-departed presidents—and many higher education institutions (HEIs) across the region find themselves a bit behind schedule and in search of ideas for how to catch up.

In our region, where temperatures range from well below 0 to over 100 degrees, heating and cooling can present a major opportunity to improve sustainability stats of a campus. Overt changes such as improving windows come to mind, but recent advancements in boiler technology and strategies for working with the heat of the sun and the cool of the earth can provide powerful, if unsexy, means of reducing emissions quickly.

Advances in biofuels

A major source of New England HEIs’ fuel usage goes to the boilers that heat their buildings. Switching to a sustainable, renewable fuel in the burner system means huge reductions in carbon emissions and lowers dependence on fossil fuels, such as coal or natural gas. Most HEIs rule out this option because biofuels, such as wood chips or pellets, require a complete new boiler system and easily cost upwards of $10 million.

A new biofuel option has emerged in “liquid wood” or “bio-oil.” Liquid wood isn’t new to the market, but the technology to burn it efficiently and safely is. This liquid fuel, made from wood in a process called pyrolysis, behaves just like traditional fuel oils in the boiler, so existing boiler equipment can be retrofitted easily—for about one tenth the cost of converting to traditional biofuels. The fuel has existed for some time, but the technology to burn it has only recently been perfected.

Since the raw wood comes from tree farms, liquid wood fuel is a 100 percent renewable resource. It's also extremely carbon-efficient because the planting of new trees (to replace those harvested to create the oil) offsets much of the carbon emissions. When Bates College, in Maine, switched its heating system to liquid wood ahead of last winter, its carbon footprint was reduced by 83 percent in a single year.

Replace boiler components

Boilers are incredibly durable. They often last decades—potentially even a century—without needing to be replaced. However, just because something isn’t broken, doesn’t mean it’s green. While many schools are still working to set up protocols to lower thermostats, they can also make use of technology that increases efficiency of the heating system automatically. For instance, boiler upgrades were part of how Bowdoin College reached its climate goal two years early.

The electrical efficiency of a boiler is determined by its ability to maintain an optimal ratio of air to fuel. Older burners set these ratios manually. Not only are they difficult to adjust, they slip over time. Upgrading the controller component of a boiler system is relatively inexpensive—most of the system can remain. With ratios dialed in by computer and maintained digitally, the sustainability gains can be huge. Installation costs can be as low as $5,000, and electrical usage can be reduced by as much as 75 percent.

Harness natural thermal energy

If your campus is climate-conscious, you’ve likely explored solar panels as a power source extensively, but there are other ways to capture the sun’s energy. Solar thermal walls are dark-colored metal plates that can be mounted on the southern side of buildings to capture the sun’s heat (even during the dead of winter) and pull warmed air into the building with fans. Heating fuel savings enable these fixtures to pay for themselves in one to eight years.

Controlling the temperature of your facility isn’t the only heating and cooling cost of a campus. Tremendous amounts of energy are expended changing the temperature of water. Geothermal wells use the Earth’s ambient temperature of about 55 degrees to give a head-start on heating water. While likely cost-prohibitive as a sustainability measure alone, campuses that may already be updating their water systems can look to make sustainability gains along the way, particularly rural campuses that rely on wells because they aren’t served by city water systems.

Merge environmental studies with engineering

The enthusiasm of students was a major driver for colleges and universities entering into climate leadership commitments in the last decade. In the years since 2007, "employability" has increasingly become a top issue on the minds of students and administrators. Campuses that connect these causes can both tap the intelligence and energy of their students while providing them with valuable workforce skills.

When updated with remote monitoring technology that tracks usage data, something as mundane as the campus boiler system can become a hands-on arena for research at the intersection of environmental studies and engineering. Colleges and universities in New England could follow the example of institutions like Maharishi University of Management in Iowa, where students get hands-on experience managing the campus’s sustainable living program, which includes sustainable heating and cooling elements. Several alumni have used skills developed in the program to enter the sustainability field or launch companies in the green energy space. At Mesalands Community College, in New Mexico—which has a 1.5-megawatt wind turbine that powers the campus and is maintained by instructors and students—graduates enter the workforce trained in wind turbine maintenance.

Rather than merely agitating for sustainability improvements on campus, institutions that create a collaborative environment for students to be part of the solutions give those students an edge as they enter the workforce. New England, where energy costs are high, winters are cold, and there’s widespread community support for climate initiatives, is an ideal place to train the next generation of building managers and engineers while preparing campuses for a sustainable future.

Dan Wallace is vice president and CEO of Preferred Utilities Manufacturing Corp.