For an all-powerful speaker

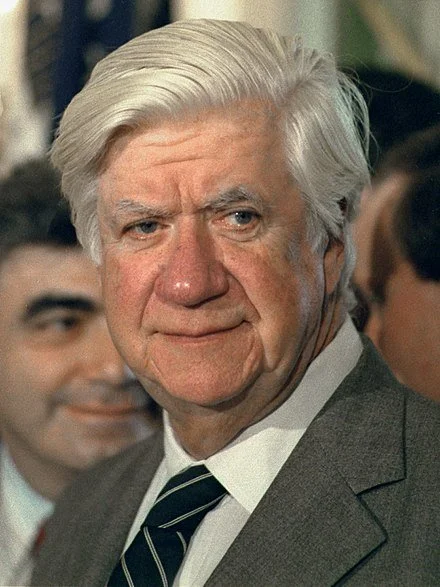

Tip O’Neill in 1978

“I think the speaker of the House in Congress should be like the Massachusetts speaker: all-powerful. He should appoint committee chairmen and remove them if they stray from the party line. He should be answerable only to the caucus, which can remove him at any time. I'd throw the seniority system out on its ear in Congress.’’

— Thomas P. (“Tip”) O’Neill Jr. (1912-1994), New Deal-style Democratic who served as speaker of the Massachusetts House (1949-1953) and speaker of the U.S. House (1977-1987). He was known for his FDR-Truman-style liberalism, pithy political sayings, most notably “All politics is local,’’ and impressive nose.

His district was centered around the northern part of Boston.

Autumn in the Alewife Linear Park, near the corner of Cedar Street and Massachusetts Avenue, North Cambridge — Tip O’Neill’s neighborhood

Taylor Witkin/Scott Nuzum: Designing seafood systems for the post-pandemic world

Photo by Gordito1869

From SeaAhead

BOSTON

While the COVID-19 pandemic directly threatens the lives of millions of patients and frontline health-care workers, it also jeopardizes the livelihoods of seafood-system workers across North America. The pandemic exposes the vulnerabilities of supply chains that criss-cross oceans, stretching across thousands of miles and demonstrates a need, and capacity, for regional food security.

Savvy seafood harvesters are often prepared for major market disruptions -- harmful algal blooms that shut down production, hurricanes that force boats back to safe harbor, ice that takes out equipment. But this pandemic is a different kind of crisis. It attacks demand as well as supply. Harvesters that rely on sales to restaurants, where 90 percent of shellfish and 75 percent of all seafood in America are consumed, are left wondering how to stay afloat if pandemic-induced shutdowns continue. The entire industry has been forced to pivot to direct-to-consumer sales models, a daunting task given that restaurants aggregate customers and bear much of the marketing burden.

While these are indeed dark times, there are rays of hope for better days. Ultimately, this crisis may lead to a reorientation and recommitment to local food systems, providing a much needed boost to local communities and restoring some resiliency in domestic food- supply chains. In addition, this crisis also may provide an opportunity to reflect upon how we might redesign our commercial fishing fleets to take advantage of a range of innovations -- including remote sensors, advanced propulsion and alternative fuel systems.

This reorientation, recommitment and reimagining will, in large part, be aided by the bluetech sector. Working as partners, local producers and tech companies have the potential to revitalize the seafood sector and create the seafood system of the future.

With international trade stalled, the pandemic is forcing producers, suppliers, and consumers to rethink America’s seafood system, where 90 percent of seafood comes from foreign sources. Much has been written recently of the collapse of domestic seafood-supply chains (NY Times, LA Times, National Fisherman, Seafood Source). Seafood processors are saddled with more fish than they can process. Fishers can’t engage in their livelihood. All the while, consumers facer empty supermarket shelves and compete for coveted grocery delivery windows on mobile apps. Moreover, with reports of Covid-19 outbreaks spreading through many of the country’s food-processing facilities, people are increasingly concerned about the chain of custody of their food and whether it is safe to eat.

Consequently, consumers have sought work-arounds to these supply chain failures by looking closer to home for seafood, relying on local farmers markets and community-supported fisheries to deliver fresh, high-quality finfish and shellfish from short, trustworthy supply chains. Whereas the “know your fisherman” ethic was a lifestyle choice in the pre-COVID-19 world, it is now gaining momentum and becoming mainstream.

And with good reason. The United States is blessed with an abundance of seafood up and down its lengthy coast. Most U.S. fish stocks are well managed, meaning that fish can be harvested sustainably. And, increasingly, we have the tools to provide traceable and transparent supply chains. Combined, these factors point to an opportunity to transform seafood-supply chains to not only increase resiliency and sustainability in the system, but also to improve economic returns for fishers and their local communities.

The Local Catch Network demonstrates the power of an engaged virtual community, and that technology does not need to be complex to be effective. Local Catch is a community-of-practice made of fishermen, suppliers, chefs, researchers and organizers committed to providing local, healthful, low-impact seafood via community- supported fisheries. Local Catch’s Seafood Finder map provides the location and contact info for nearly 120 businesses that distribute to over 500 locations in the U.S. and Canada, making it easy for consumers to find local seafood providers and distribution points. Though businesses within the network are struggling, as consumers make a concerted effort to support their fishermen and farmer neighbors, some seafood providers are well positioned to weather the crisis, and are even doing more business than usual.

While Local Catch Network was conceived in the pre-COVID-19 world, the virus has only served to reinforce its underlying thesis -- that the seafood-supply-chain network was ripe for disruption. This and countless other groups, such as SeaAhead members Oyster Common, Oyster Tracker and LegitFish hope that their efforts bring greater value to fishers and the coastal communities in which they live, in the process demonstrating the transformative possibilities of the bluetech space.

If you want to learn more, check out the Social FISHtancing podcast

xxx

Taylor Witkin is the Bluetech Desk Manager at the Cambridge Innovation Center (CIC) and works with SeaAhead to manage and grow the Bluetech Innovation Hub, in Boston. Before joining CIC, he was the Network Coordinator for the Local Catch Network and organized the 2019 Local Seafood Summit. He also conducted research for the University of Maine on adaptations by stakeholders and supply chains in the lobster industry. His seafood-systems research has been published in the journal Fisheries Research.

Scott Nuzum is a strategy consultant and futurist at VNF Solutions LLC and a lawyer with Van Ness Feldman LLP. He helps organizations assess and understand the implications of technological, environmental and geopolitical change and works with clients to craft strategies to become more resilient in the face of this disruption. In addition, he advises innovative companies and start-ups operating in the environmental-, energy- and social- impact spaces on a range of issues, including providing input and feedback on engagement strategies with potential investors and regulators. Before joining VNF, he was a policy adviser at the White House Council on Environmental Quality and a lawyer at the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Llewellyn King: Novel revives Vietnam War memories and lessons

The Vietnam War was much with me. I never made it to Vietnam during the war. But the war came to me in every job I had between 1961 and 1973.

It is not that I did not try to get to Vietnam as a correspondent, or even as a soldier. I registered for the draft when I arrived in the United States in 1963, but I was rejected because my eyesight was poor, I was married, and I was too old.

I started my long-distance association with the war when I was working for Independent Television News in London in 1961, and continued it when I moved over to the BBC. I was always selected as the writer for the Vietnam segments.

At The Herald Tribune in New York, on my first night, I was asked to pull all the files together for the lead story: Vietnam. Later at The Washington Daily News and The Washington Post, Vietnam always found me.

Now comes a novel and the war finds me again, as I read about correspondents David Halberstam and Peter Arnett; U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin, who was delusional about the situation; Nguyen Van Thieiu, the president of South Vietnam until his ouster. It is all as fresh as if it were the file coming off the teleprinter today.

The novel is Escape from Saigon and its authors, Michael Morris and Dick Pirozzolo, tell the last, desperate days of Saigon in 1975. It is a novel where the end is known, but not known; where the tension ratchets up each day of the countdown to evacuation on April 29.

In Washington, Congress had refused President Gerald Ford’s last attempt to bolster aid to South Vietnam with a final $722 million. The major U.S. military participation ended with the peace treaty of 1973. For two years, the South Vietnamese had struggled on with U.S. support but without ground troops. The North Vietnamese would roundly violate the peace, and the South Vietnamese would live in hope that the United States would not let them be overrun. Forlorn hope.

The United States had lost interest in the war, after it had been so torn apart by it, and wanted no more part of a land war in Asia, or at that time, a land war anywhere. More than 58,000 Americans and an untold number of Vietnamese had perished.

Lessons? You draw them: secret plans, ground troops, aerial war, insuperable U.S. military might. These ideas are flying again about other regions of the world. Beware. Read this novel.

I have often thought that if the Kennedy brain trust had read The Quiet American, Graham Greene’s masterful novel about Vietnam, published in 1955, things would have turned out differently. We might have shunned involvement on the election of Jack Kennedy.

Escape from Saigon has the same ring of authenticity. It should: the authors both served in Vietnam. Morris was sent to Vietnam when he was just 19 years old and, as an infantry sergeant in Northern 1 Corps, he saw some of the fiercest fighting of the war. He was wounded and his bravery was rewarded with a Purple Heart.

Pirozzolo was an Air Force information officer in Saigon. Perhaps that is why the city is so well described, from the watering holes to hotels, like the Caravelle and the Continental, where so many journalists stayed and drank. Drinking was a part of Saigon in war.

When I finally made it to Vietnam, in 1995, I traced the war from Hanoi, replete with its French boulevards down through Da Nang, Hue and China Beach. All so peaceful, after so much bloodshed. Battlefields are that way.

Escape could be a sad book, or a book of recrimination, or an attack on the American role. Instead, it is a novel of facts told through the lives of the people: journalists, a bar keeper, a priest, a CIA official, South Vietnamese who worked for the Americans and sometimes betrayed them, and those who fled by plane and boat.

The novel is exceptional in authenticity. Its portrait of a city in extremis is chilling and completely engrossing. It will take many back and some forward -- forward to new foreign involvements.

Llewellyn King (llewellynking1@gmail.com) is executive producer and host of “White House Chronicle,” on PBS.