Call pest control?And treating Norman Rockwell

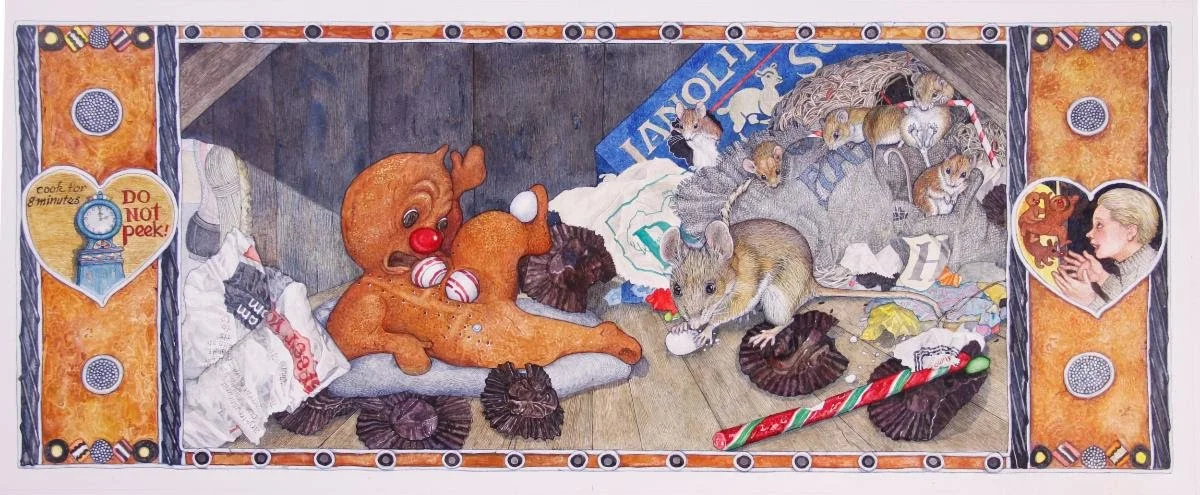

“Scritchy Scratchy,” by Jan Brett (watercolor on paper, illustration for Gingerbread Friends), in the show “Jan Brett: Stories Near and Far,’’ at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Mass., through March 6.

Ms. Brett is the author/illustrator of such books for kids as The Mitten, Cozy and Gingerbread Baby. She has homes in the Berkshires and in Norwell, Mass., where she grew up.

The North River, with beautiful marshes, forms the southeast boundary of Norwell.

The famous Austen Riggs Center, a psychiatric institution in Stockbridge, the Berkshires town that the famed painter and illustrator Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) moved to at least in part because of Riggs, where he and his second wife, Mary Barstow, were both treated for mental illness. His wife, the more seriously ill of the two, suffered from depression and alcoholism and Rockwell from depression and anxiety.

The very expensive Riggs had the reputation of drawing well-known patients and celebrated psychiatrists.

Rockwell once said: "I paint life as I would like it to be.’’

Third person rural

By ROBERT WHITCOMB

While driving through the Vermont hills a few weeks ago, I thought about two artists much associated with New England’s rural parts — Norman Rockwell and Robert Frost — and the relationship between their lucrative rural public personas and private lives. No surprise that there was quite a gap! For one thing, they were born outside New England — Frost in San Francisco and Rockwell in New York City — and grew up in cities. More importantly, their public images were, and are, at considerable variance from their personal lives.

Norman Rockwell has been much in the news again lately because of the new book “American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell,” by Deborah Solomon. In it, she not only discusses Rockwell’s genius as an illustrator, but also a private life that was often quite tormented. (Like, I would guess, most lives.)

Ms. Solomon discusses Rockwell’s depression and anxiety. And she speculates (to the dismay of the artist’s family) that his life may have been complicated by homoerotic longings that may (or may not?) have expressed themselves in his many pictures of winsome, Tom Sawyer-like boys and handsome square-jawed men. He also had three troubled marriages and was a hypochondriac — and to the pleasure of his millions of fans, a workaholic.

Stockbridge, Mass., the Berkshires town whose scenes provided many of the ideas behind Rockwell’s famous illustrations, is also the site of the Austen Riggs Center, the mental hospital whose staff has treated many celebrities. Ms. Solomon says that Rockwell and his second wife, Mary Barstow, an alcoholic, moved there from Arlington, Vt., so that Mrs. Rockwell could be treated for depression. Rockwell himself used Austen Riggs’s services.

And yet the pictures that Norman Rockwell painted of the town are mostly upbeat — evoking a small-town communitarian paradise. “I paint life the way I want it to be,” he famously said.

Then there was the mating of modernist and 19th century poetry that is the great work of Robert Frost. Frost, like Rockwell, was a city boy whom the public came to primarily associate with rural New England themes, but innocent and Arcadian his poems are not. Many evoke a chilly or even malevolent universe. (My favorite is “Design.”) Far more Ethan Frome than Currier & Ives.

But as his fame spread in the English-speaking world (he first became well-known in England, where he lived in 1912-15), that he looked like Hollywood’s idea of a Yankee farmer, and his folksy genial manner (for public consumption, anyway) tended to overcome in the public mind the darkness of his poems. He could have been a character in a Rockwell painting. This was in part intentional: Being seen as a charming cracker-barrel philosopher/poet brought in the lecture and poet-in-residence fees. He became the most famous poet in America.

Thus we have the curious transformation of the deeply intellectual Frost (whose characters were mostly ordinary country people, whose speech patterns and emotions he was deeply familiar with) into an icon of popular culture.

Consider the revision in Norman Rockwell’s reputation from “merely” a “fine popular illustrator” to being seen as a kind of great artist, with aesthetic links to other masters going back to the Renaissance. It takes a long time for society to figure out what it really thinks of its artists and politicians.

***

Memoirs have been one of the comparatively strong parts of the book business in recent years. With aging Baby Boomers, expect a lot more. A few recent ones:

‘’Whiplash: When the Vietnam War Rolled a Hand Grenade Into the Animal House,” by Denis O’Neill, is a mildly fictionalized account of the 1969-1970 academic year at Dartmouth College. O’Neill is a journalist, screenwriter and musician. On Dec. 1, 1969, the Selective Service System held the first lottery since World War II for the draft, bringing great anxiety to some and relief to others, and “The Sixties,” as we know them, reached their crazy crescendo. (You could say that “The Sixties” as a cultural phenomenon didn’t really end until, say, 1972.)

Then there’s Rhode Island investment mogul Tom DePetrillo’s book about the downs (including personal bankrupty) but bigger ups of his career. He was one of 11 children and a school dropout before he made a fortune as an investor. The book provides chatty and colorful advice and observations on business, public policy, politics and life in general.

Finally there’s Ralph Barlow’s “Beneficent Church in Providence: A Church Engaged with an Emerging New World,” the Rev. Mr. Barlow’s memoir of running the church from 1964 to 1997, during which this downtown Congregational institution’s experience included many of the recent social upheavals of American society.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb4@cox.net), a biweekly contributor, is a Providence-based writer and editor. He blogs at newenglanddiary.com.

The way he wanted life to look

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), “The Bridge Game,” 1948, oil on canvas, published by Saturday Evening Post, May 15, 1948 cover Image Courtesy of National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, RI., cover image © SEPS: www.curtispublishing.com.

There’s another picture below.(Rerunning this posting from the pre-renovation version of New England Diary a few weeks ago.)

The New York Times seems to be on a Norman Rockwell kick, with a long review of a new book out about him and a travel piece about Arlington, Vt., where he lived for a long time.

That was before he moved to Stockbridge, Mass, in the Berkshires, to, among other things, be closer to Austen Riggs, the mental hospital identified with many celebrity patients.

As Deborah Solomon (who also wrote the travel story) writes in “American Mirror: The Art and Life of Norman Rockwell,” his life was far more complex and darker than most of his beautiful art. That he was a troubled man (who ain’t?) is not news, but Ms. Solomon puts it together very well indeed.

He was apparently conflicted about homosexual longings, had three troubled marriages and was a lifelong hypochondriac. The Thoreau line about “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation” comes to mind. Still, he obviously found much comfort and joy in his studio. Do too many writers these days make too much of sexual conflicts? Maybe a highly creative person’s biggest trauma is the difficulty of finding meaning in a seemingly chaotic world, a torturous search for ultimate meaning.

Some of this reminds me of the strange story of Robert Frost, whose public image as a sort of quaint, folksy, friendly rural poet was so false. In fact, Frost, a kind of Modernist, used his New England settings to explore existential quandaries; and he could be a very nasty man.

Many of his poems were dark, dark, dark. Take a look at his poem design “Design”.

But, in part because his folksy image got him many lucrative lecture gigs, he played along with it, to a point (while winking).

But then, behind almost family’s door is conflict and mental illness of varying seriousness. In some way, maybe imaginative repression and diversion, Rockwell got great popular art done despite, or because of, his problems, through vast technical skill, knowledge of other masters’ work and a rich visual imagination.

The Rockwell renaissance also reminds me of how much many of us miss the golden age of magazines, such as The Saturday Evening Post, for which Rockwell did so much work. The weekly arrival of pubs such as The Post and Life magazine was a joy that I, anyway, have never found with TV, the Internet and newspapers (with the possible exception of the beautiful old New York Herald Tribune).

That is probably ungrateful, since newspapers paid for most of my upkeep for almost 44 years.

Speaking of the past, I was pleasantly surprised to see that John Wilmerding, my art-history professor of almost a half century ago at Dartmouth, was the reviewer of Ms. Solomon’s fine new book. Mr, Wilmerding, an heir to great Havemeyer sugar fortune in New York, also has one of America’s greatest collections of American art, much of which he is giving away.

The best places to see Rockwell work are the National Museum of American Illustration, in Newport, and, the Norman Rockwell Museum, in Stockbridge.

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), ”Volunteer Fireman,” 1931, oil on canvas, published by Saturday Evening Post, March 28, 1931 cover image Courtesy of National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, RI. Saturday Evening Post cover image © SEPS: www.curtispublishing.com