Amazon to pay for tuitions at UConn and other schools

Aerial view of UConn’s flagship campus, in Storrs

— Photo by Global Jet

Edited from a report by the New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“Amazon announced that it will now offer fully funded tuition to local hourly Amazon workers who attend the University of Connecticut {and Capital Community College, in Hartford} as well as some other colleges around America. This effort is a part of Amazon’s Career Choice program, in which the company partners with dozens of higher education institutions to help ‘upskill’ Amazon workers through the funding of their college tuitions.

“Ruth Kustoff, director of continuing and professional education at UConn, said that the university is ‘excited to be part of the Amazon Career Choice network,’ and is ‘looking forward to providing higher-education opportunities to Amazon employees through our Storrs and regional campuses.’ With Amazon’s investment of $1.2 billion into education projects, the company aims to assist 300,000 employees in obtaining new degrees and certifications by 2025.’’

Capital Community College, in downtown Hartford.

Amazon octopus keep stretching out its arms

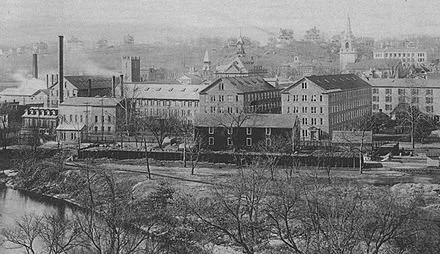

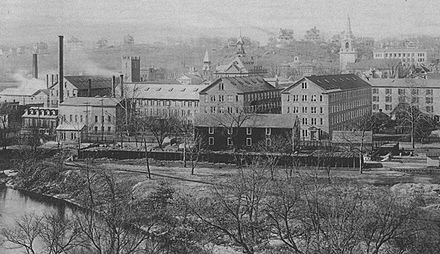

Goodyear Metallic Rubber Shoe Company and downtown Naugatuck (c. 1890). The many industrial firms in Naugatuck and Waterbury in the communities’ industrial heyday, from the mid-19th Century through the 1960’s, dumped toxic waste into the Naugatuck River, much of which eventually flowed into Long Island Sound.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com):

“Amazon plans to develop a new distribution facility in New Haven County, Conn….Bluewater Property Group, a developer from Pennsylvania, has begun taking steps to create a tremendous Amazon distribution facility on the border of Waterbury and Naugatuck.

“Though the development is far from completion and is awaiting approval, residents of Waterbury and Naugatuck and members of the Connecticut (congressional) delegation are optimistic about the prosperity that this facility would bring to the county, and even the state.

“‘It has the potential to create up to 1,000 new jobs and go a long way in supporting these communities in their broader revitalization efforts,’ stated Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont. U.S. Rep. Jahana Hayes shared in this assertion, stating that this influx of jobs would benefit the middle class and the blue-collar workers in the area.’’

Sam Pizzigati: Amazon’s business model can kill

From OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Old-school home-improvement contractors have a piece of folk wisdom they love to share with prospective clients. “Listen,” they like to say. “I can do this job fast, I can do it cheap, or I can do it well. But I can’t do all three.”

This wisdom has been around forever. But not everyone gets it — take billionaire Jeff Bezos. His Amazon empire prides itself on delivering good results fast and cheap.

That works well enough for Bezos, now worth around $200 billion. And Amazon consumers, the company PR maintains, can get almost whatever they want quickly and cheaply. But for Amazon workers — and our broader society — Amazon’s empire building has been anything but good.

That became disastrously apparent this month, when a tornado swept through Edwardsville, Ill., leaving six Amazon warehouse workers dead. Debris from their workplace turned up “tens of miles” away, the National Weather Service reported.

Unfortunately, this tragedy should not have taken anyone by surprise.

Why did Amazon locate its Edwardsville operations right in Tornado Alley? No mystery there. Edwardsville’s plentiful acreage and easy access to interstate highways, airports, and other transport offered Amazon the promise of speedy delivery times and lower delivery costs.

Check fast. Check cheap. But the warehouse went up with no special attention to tornado safety. That would have raised the cost.

OSHA — the federal occupational health and safety agency — has now begun an investigation. Since the deaths in Edwardsville, Amazon workers throughout the southern Illinois area have been ripping the company for failing to conduct tornado drills and expecting workers to keep working even after alarms ring out.

Amazon’s “storm shelter” spaces for Edwardsville workers turned out to have another name: bathrooms. Moments before the tornado’s arrival, Edwardsville worker Craig Yost told local news, Amazon supervisors were directing people into their worksite’s bathroom “shelters.”

“The walls caved in, and I got pinned to the ground by a giant block of concrete,” Yost said. “On top of my left knee was a door from the bathroom stall, and my head was on that with my left arm wrapped around my head. I could just move my right hand and foot.”

Meanwhile, the company has been actively exercising its considerable power to prevent the one turn of events that could reliably keep Amazon on its safety toes: a union. Earlier this year, Amazon quashed a union drive at its Bessemer, Ala., warehouse so egregiously that the National Labor Relations board has ordered a do-over on the election.

But the problem goes beyond Amazon. Our nation’s corporate giants have been on a ferocious 50-year offensive against collective bargaining.

In the mid-20th Century, over a third of America’s private-sector workers belonged to unions. Now only 6.3 percent of private-sector workers carry union cards, despite polling data showing that the share of nonunion workers who want a union at their worksite has increased markedly.

Corporate America’s squeeze on unions has kept wages low, share prices high and compensation for top executives at stratospheric levels. Earlier this year, Institute for Policy Studies research revealed that CEOs at America’s 100 largest low-wage employers saw their personal compensation jump by $1,862,270 in 2020.

Over the past year, Jeff Bezos has seen his wealth soar by over $4 billion — seven times the annual budget of OSHA, the agency investigating the disaster at his Edwardsville warehouse. So here’s an idea for lawmakers in Washington: A 5 percent annual federal wealth tax on those Bezos billions could quadruple the annual OSHA budget — and then quadruple it again.

Amazon’s relentless quest to sell goods fast and cheap has rewarded Bezos tremendously, but it’s come at a huge cost for the rest of us. If the company rebuilds its Edwardsville warehouse, Bezos should listen to his handyma\

Sam Pizzigati, who is based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His latest books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Amazon to hire 1,500 workers in Mass. to deal with holiday crush

“Battle of the Amazons (1618), ‘‘by Peter Paul Rubens

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Amazon recently announced that it plans to hire 1,500 seasonal workers in Massachusetts to help meet the holiday demands. This is a part of an effort to hire 150,000 seasonal workers around the country.

“Caitlyn McLaughlin, a spokesperson for Amazon, confirmed the announcement while reiterating that the supply-chain challenges that are being experienced will affect consumers around the world. ‘Everyone at Amazon is working to anticipate and prepare for various scenarios to ensure positive delivery experiences this holiday season, for instance, by launching promotions to encourage earlier shopping,’ said McLaughlin.

“Amazon is one of Massachusetts five largest employers, according to the Business Journal, and covers both the tech industry and the retail industry. Over this past summer the company had 20,000 positions available in the state for both part time and full-time positions in both industries.’’

‘The company way’

Amazon fulfillment center in San Fernando de Henares, Spain

— Photo by Álvaro Ibáñez

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Amazon wants to build a gigantic, nearly 4-million-square-foot distribution center on 195 acres off Route 6 in Johnston, whose leaders seem to love the idea, even with the 20-year property-tax break involved. After all, there would purportedly be 1,500 full-time jobs (at least until more Amazonian automation eliminates some of them), and the enterprise is offering some specific goodies to Johnston and the state as sweeteners, though they’re minuscule considering the profit that the company would make from this huge operation in densely populated and generally prosperous southern New England.

This project would mean hundreds of tractor-trailer trips in and out of this behemoth every day, and so the area’s traffic and the environment (lots of fragrant truck exhaust!) would, to say the least, be affected big time, and probably so would be the region’s small retailers, who would find it even harder to compete with the Amazon octopus as it gets more stuff to local customers even faster.

But, hey, all those jobs! And the facility would be good news for southeastern New England’s many fine orthopedic surgeons and physical therapists since Amazon is well known for its high rates of worker injuries suffered as a result of its grueling work demands enforced via Orwellian surveillance.

Here’s an interesting Amazon controversy that folks around here might want to read.

“A: I play it the company way

Where the company puts me, there I'll stay.

B: But what is your point of view?

A: I have no point of view!

Supposing the company thinks... I think so too!’’

-- From “The Company Way,’’ in How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, by Frank Loesser (1910-1969), Broadway lyricist and composer.

Janie Grice: For an essential workers' bill of rights

From OtherWords.org

During the pandemic, essential workers have become public heroes. These frontline workers include tens of millions of retail employees, from those who stock our grocery shelves to those filling orders for Amazon.

With so many people seeing firsthand how low-wage workers make our society function, we have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to transform our society so that everyone can earn quality pay and benefits.

But beyond symbolic displays of gratitude, essential retail workers have not yet seen this transformation.

At Walmart, the largest private employer in the country, workers are still not receiving adequate hazard pay, safety protections or paid leave. The company remains the top employer of workers who are forced to rely on food stamps and other aid.

At Amazon, employees still face rigid limits on bathroom breaks and other policies that compromise their health and safety in the midst of a pandemic. At least 20,000 Amazon employees have tested positive for COVID-19.

These issues are deeply personal to me.

For four years, I worked at my local Walmart as a cashier and later as a customer-service manager — all while raising my son as a single mother and working on a bachelor’s degree. I started out making only $7.78 an hour and was never able to get a full-time position, let alone a stable schedule.

I understand the stresses faced by retail workers at our country’s largest employers, including struggling to pay bills and not being able to care for a sick child because of unpredictable hours and low wages.

Despite the challenges of the job, I got my degree in social work and now support retail workers across the country as an organizer for United for Respect. This national organization of working people fights for bold policies that would improve lives, particularly those in the retail industry.

One of our priority goals is an Essential Workers Bill of Rights, which would guarantee improved health and safety protections, universal health care, increased pay and paid leave, and whistleblower protection.

Workers also need a real voice in policy matters that affect our lives, from union organizing rights to personal protective equipment. So we’re pushing to get worker representation on corporate boards.

Without these rights, corporate executives and politicians will continue to put their interests before those of essential workers and their families. And retail workers, especially Black women like me, will continue to live in poverty while working for some of the largest and wealthiest employers in the world.

During the pandemic, the wealth of Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos and Walmart’s Walton family has skyrocketed to record levels, according to a new report by Bargaining for the Common Good, the Institute for Policy Studies, and United for Respect. The contrast between this wealth and the struggles essential workers face is shameful.

If this nation wants a real conversation about dignity for people like me and the people I organize, then we have to embrace bold solutions. And we can start with an Essential Workers Bill of Rights and a voice for workers in decision making.

Think about what corporate America would look like if workers actually had a seat at the table. Corporations would prioritize investments in their workers instead of padding their CEOs’ pockets. The millions of retail workers who now have to rely on food stamps and other public assistance could provide for their families.

Let’s push toward this dream by expanding opportunities for the working people who are critical to the health and security of our nation — today, during the pandemic, and beyond.

Janie Grice is an organizer with United for Respect, based in Marion, S.C.

— Photo by Lars Frantzen

Hancock, Amazon team up on health-measurement device

John Hancock Life Insurance Co.’s current headquarters, at 197 Clarendon St., built in 1922, and not to be confused with the glassy office tower at 200 Clarendon St. that’s still called the John Hancock Tower, was completed in 1976 and remains, at 60 stories, the tallest building in Boston.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

Boston-based John Hancock Life Insurance Co. has formed a partnership with Amazon on the tech giant’s recently unveiled Halo band, a wearable device that will track a variety of activities such as exercise and sleeping patterns.

John Hancock life-insurance policyholders will be able to earn rewards and premium discounts based on their use of the new technology. Use of the new technology is intended to help policyholders embrace healthier living habits. The insurer is not new to incorporating technology into its business model, and has existing partnerships with both Apple Inc. and Google parent company Alphabet Inc.

“Integrating Amazon Halo into our life insurance ownership experience will enable us to continue to transform the role our industry plays in our customers’ lives,” said Brooks Tingle, President and CEO of John Hancock Insurance in a press release. “At John Hancock, we believe a life insurance company is in a unique position to help customers live longer, healthier lives, and by integrating Amazon’s new health and wellness technology into our program, we can create a more meaningful, engaging and holistic experience for our customers.”

Read more from the Boston Business Journal.

Brian Wakamo: Sports walkouts: Imagine what an Amazon strike could do

Via OtherWords.org

First, the Milwaukee Bucks refused to take the court in their playoff game against the Orlando Magic. Then other teams followed suit, leading to a three-day wildcat strike in the National Basketball Association.

The Bucks were protesting the police shooting of Jacob Blake in nearby Kenosha, Wis., but they helped ignite a wave of athletic activism for racial justice. Other leagues followed suit.

Players in the women’s NBA, who often lead athlete protests, joined the strike. Some Major League Baseball teams — including the Milwaukee Brewers — refused to play multiple games as well. So did Major League Soccer players.

And Naomi Osaka, two-time tennis Grand Slam winner, announced she would not play her semi-final match as a protest. She next appeared wearing a face mask with Breonna Taylor’s name on it.

It was a seismic moment in the history of sports.

We’ve seen players use their platform to advocate for social justice, going all the way back to Jackie Robinson, Muhammad Ali and Billie Jean King. And we’ve seen players strike for better collective bargaining agreements.

What’s new are these labor actions for social justice — especially across multiple sports and leagues. It’s unprecedented.

These shows of strength and solidarity had immediate consequences, including at the NBA offices, where around 100 employees struck in solidarity. Within a few days, NBA owners and players announced a raft of initiatives to improve voter access in NBA arenas and to invest in a joint social justice coalition among coaches, players, and owners.

As these athletes have shown, striking does not need to be reserved exclusively for higher wages or a better contract. NBA players have a strong players union and an incredibly well negotiated collective bargaining agreement, but they knew they had the power to amplify a national conversation about police violence. It’s inspiring that they chose to use it.

It’s also an inspiring story about the power of all workers.

Few workers are as well paid as professional athletes, and most have more to lose from running afoul of their employers. But there’s a lesson here for them, too: Workers make the company run, not the CEOs and owners. Withholding that work can force immense changes.

After all, if a handful of athletes refusing to play can yield such immediate results, imagine what would happen if long-suffering, underpaid Amazon or Wal-Mart workers — or both — pulled off a national strike. They could virtually shut down the economy and win the fair treatment they’ve been demanding for years.

That’s what postal workers did in a 1970 postal strike, which completely halted all mail deliveries, even as President Nixon attempted to use the National Guard to deliver the mail. Nixon failed miserably, and postal workers won collective-bargaining rights, higher wages and the four postal unions we have today.

As for those well-paid athletes? I hope they’ll force their employers to take tangible steps in other fights — like for racial justice, a fairer immigration system, and action on climate change.

These athletes just showed us all a path forward. I hope more workers are inspired by their example.

Brian Wakamo is an inequality researcher at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Don Pesci: Amazon strikes back at Willy Loman

"Sometimes...it's better for a man just to walk away. But if you can't walk away? I guess that's when it's tough.”

—- The Willy Loman character in Death of a Salesman

The old saying is “You can’t fight City Hall.” That is partly true. City Hall is huge and more powerful than you. The gods of government have resources denied to the little people, but then government is supposed to be on the side of the little people, as is the media, a presumed joint support that tends to even the perpetual battle between the lions of the market place and … let’s call him Willy, after Willy Loman, the chief character in Arthur Miller’s play Death of a Salesman.

The Willy of this piece is a Connecticut salesman – there are many of them – who do business with Amazon. And Willy has a problem that will not be settled by the usual white-hatted Attorney General of Connecticut or legislators who weep over the little guy or the media, afflicters of the comfortable and comforters of the afflicted. You can bet your house on that.

In the world of commerce, Amazon is bigger than God. It seems only hours ago that the equivalent of City Hall in Connecticut, state government – not only in Connecticut and its environs, but everywhere in the nation – was breathing heavy in strenuous attempts to lure Amazon into their beds, the better to ravish the e-commerce giant with taxes.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo was dashed when Amazon, searching for a place in the Northeast to locate part of its headquarters, kissed the state goodbye. Pummeled by progressives in New York -- among them Mayor of New York City Bill de Blasio (birth name Warren Wilhelm Jr.) and U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez -- for having considered the governor's crony-capitalist $3 billion tax break, the company withdrew an offer to plop a new facility in New York that might have generated $27 billion in revenue.

“What happened is the greatest tragedy that I have seen since I have been in government,” moaned a grievously wounded Cuomo.

Crony capitalist blood began to beat like a tom-tom in former Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy’s veins, and it still swells in Gov. Ned Lamont’s heart. Both Malloy and Lamont are crony-capitalist governors -- is there any other kind in the high-taxed Northeast? Wouldn’t it be grand to net such a massive leviathan? Malloy moved on, Lamont is fishing still.

But salesman Willy is dangling at the end of an economic rope, and he writes, somewhat desperately:

“If I sell something on Amazon, they take 15% as a referral fee. This covers marketing, customer acquisition, and credit card fees. If I use Amazon to warehouse and ship the item, they then charge a pick and pack fee. That is also taxed. So if I do $1M a year in gross sales, Amazon ends up taking about 33%."

Adding the cost of doing business with Amazon, Willy notes “$330,000 in fees, with 6.35% sales tax is almost $21,000 a year. You should understand that Amazon is half of e-commerce. Third party sellers [like Willy] represent over half of their sales. Connecticut, through its tax additions, just made it impossible for 25% of e-commerce to do business here.”

Along with his note to Connecticut Commentary, Willy enclosed the “Dear Willy” letter he had received from god:

The "Dear Seller" letter Willy received read in part:

“Amazon is required to collect taxes on Selling on Amazon fees in Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, South Dakota or West Virginia, based on each state’s tax rates. Selling on Amazon Fees include the Referral Fee, Subscription Fee, Variable Closing Fee, Per-item Fee, Promotion & Merchandising Fee, Refund Commission Fee, Checkout by Amazon, and Sales Tax Collection Fee... If your business is located outside Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, South Dakota or West Virginia, we will not collect sales tax on the Selling on Amazon fee you pay.

“Amazon is required to collect taxes on FBA Prep Services in Arizona, Connecticut, Illinois or West Virginia, based on each state’s tax rates. FBA inventory prep fees include the Labelling Fee, Polybagging Fee, Bubblewrap Fee, Taping Fee, and Opaque Bagging Fee...

“You will be able to view the sales tax collected on your fees in the transaction details page of your Payments reports.”

Willy is a Connecticut native with deep roots in the state. He’s married with young childern. And the blade of crony capitalism has fallen bloodily on Willy’s neck, because he is, in fact, an independent businessman who is expected to shut up and pay. Crony capitalism is a complex arrangement in which tax heavy states such as Connecticut and New York supply seed tax money to super-leviathans like Amazon as inducements to locate in the states; the companies then pass along to its customers and third party salesmen like Willy the costs they incur from their location in a high tax state like Connecticut. But the tax axe invariably falls on Willy’s neck. Large companies are tax collectors, not tax payers. The real taxpayers are those who consume the products and services of companies such as Amazon – and small businesses like Willy’s from whom Amazon recovers the additional costs incurred by tax increases.

It will not take long for Willy to realize “Sometimes...it's better for a man just to walk away.” No one profits when Willy walks. It would be well for legislators to remember the line in Willy’s letter. Connecticut, along with a handful of other states singled out in Amazon’s “Dear Seller” letter, has “through its tax additions,” Willy writes, “just made it impossible for 25% of e-commerce to do business here.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn.-based columnist.

Posted by Don Pesci at 2:04 PM

Labels: Cuomo, Lamont, Malloy, Willy Loman

Mass. takes careful approach to luring sexy companies

“The Amazon Spheres’’ at the company’s headquarters, in Seattle.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Amazon already has thousands of employees in tech center Greater Boston and will probably add several thousands more, perhaps mostly along the South Boston waterfront, in the wake of the apparent demise of an Amazon “second headquarters’’ in New York City. But this won’t be due to the sort of massive incentives the “populist’’ reaction to which blew up the Amazon-New York deal.

As seen in the deal crafted by Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker (a highly successful former businessman and top-notch numbers cruncher) and the generally economically reality-based Boston Mayor Marty Walsh to lure General Electric headquarters, Massachusetts has been quite conservative in crafting incentive packages. Shirley Leung had an interesting column on the GE deal. To read it, please hit this link.

Rhode Island might also get some Amazon jobs — probably design-related — because of the New York news.

The ambiguities of the Amazon mercantile jungle

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Boston did well in failing to snare an Amazon “Second (or is it third?) Headquarters’’. The hysterically hyped project would have overwhelmed city services; stolen a lot of tech talent from the startups that are the foundation of the region’s economic future; worsened the city’s traffic woes, and driven up already sky-high housing costs.

And it’s unlikely that Boston and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts would have come up with a bribe to Amazon’s Jeff Bezos that would have been big enough to offset Boston’s drawbacks, especially that it’s probably too small for the likes of Amazon. Despite the company’s show of looking all over America as a place for a “Second Headquarters (which of course turned out to be two “Second Headquarters’’ – New York and metro Washington, D.C.), it probably always planned to set up in cities too big to be overwhelmed by it, and with many, many techies already in residence. The apparently bogus national auction seems to have raised the bribe money that New York and Virginia, whose Washington inner suburb of Arlington, Va., won the prize, were willing to pay. Amazon says it will put 25,000 employees in each place.

Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker and Boston Mayor Marty Walsh were unwilling to get into a bidding war with the rest of the country for the projects.

New York State is giving the company a package that includes $1.525 billion in incentives, including $1.2 billion over the next 10 years as part of the state’ s Excelsior tax credit. The state also will help Amazon with infrastructure upgrades, job-training programs and even assistance “securing access to a helipad”. There’s still some confusion about the total package, but by one measurement, it works out to $48,000 per job.

Virginia, for its part, is giving the company an incentive package worth $573 million, including $550 million in cash grants – and a helipad (for Bezos’s convenience to commute to his Washington Post?) in Arlington, right across the river from Washington, D.C. The Old Dominion also pledged $250 million to help Virginia Tech build a campus in Alexandria, near the Amazon site, with a focus on computer science and software engineering degrees. Folks are still trying to figure out the precise total cost.

By one estimate in this rather confusing bag of bribes, the basic package works out to $22,000 per job. We’ll see.

(As sop to the Heartland, Amazon will also put a 5,000-person facility in Nashville, at an estimated $13,000 a job.)

So the individuals and companies already in New York and Virginia will subsidize through their taxes an enterprise that had $178 billion in 2017 revenues and is run by the world’s richest person. And of course it’s impossible to know how well Amazon will be doing in a decade. Might it become the online version of Sears? Nothing lasts.

Think of how much stronger their economic development would be if New York and Virginia had put the bribe money into improving transportation infrastructure, education and other stuff that would make their markets better for everyone!

And will Amazon keep its promise to create all those jobs? Don’t bet on it! Big companies are notorious for breaking employment promises. An irritating recent example:

Wisconsin, with an outrageous $4 billion subsidy, lured Foxconn, the Taiwanese manufacturer infamous for not keeping employment promises, to the state with the promise of 13,000 jobs. But the company now plans to employ only a quarter of that; much of the work will be done by robots. You can bet that Foxconn would like all of the work done by robots! One estimate is that the project works out to $500,000 per Foxconn job.

No wonder that Scott Walker, the Republican governor who pushed for this deal, just lost his re-election bid. But then, Democratic and Republican governors and mayors do these deals with enthusiasm.

The politicians know that such extravaganzas sound great, for a while, and that few citizens look into the fine print or scrutinize these sweetheart deals for their long-term macro-economic effects. And by the time that the full bill comes due, the politicians who initially got credit have moved on to something else.

Anyway, such places as tech-rich Greater Boston (and less tech-rich Providence) would do better to make their communities better places in which to start and nurture companies than to break their banks by trying to get big ones from far away whose loyalty is apt to be remarkably evanescent. That isn’t to say that Boston (which already has a couple of thousand Amazonians) and Providence (with its graphic and other designers) won’t benefit from spillover Amazon jobs from the New York operation. They probably will.

A March 2018 report by the Brookings Institution says that state and local governments give up to $90 billion worth of subsidies to individual businesses each year. How much of this is worth it? To read the report, please hit this link.

Columbus, Ohio, offers an example of how an economic-development policy delighting in diversification, encouraging local startups, and improving local amenities and infrastructure, as opposed to focusing on luring a big, fat famous company, as well as strong civic engagement by a city’s established business community, can pay off.

From 2000 to 2009, Columbus added 12,500 jobs. From 2010 to the present, it has added 158,000!

To read more, please hit this link.

Llewellyn King: Will Bezos's kiss be lethal?

On the waterfront of the Long Island City part of New York City. It’s the flood-prone area where Amazon will put one of its “Second Headquarters.’’

Having run around the country as a modern Prince Charming in search of Cinderella, Jeff Bezos, Amazon's boss, has decided that two hopefuls fit the slipper: Crystal City, Va., part of Arlington, and the Long Island City part of the New York city borough of Queens.

But these Cinderellas aren’t to be carried off to live happily ever after in Amazon Castle. No, there are dowries to be paid -- about $2 billion each in tax abatement and other goodies. These beauties are no bargain.

In fact, New York City and Washington, D.C. -- Queens is a borough of New York and Crystal City is a Virginia suburb, south of Washington -- may be prostrating themselves to gain possibly 25,000 jobs in an unhappy, taxpayer-funded alliance.

The theories as to why Bezos chose these locations abound. The dominant one is that high-tech companies must follow high-tech workers. That explains why Boston and San Francisco are overheated along with, yes, New York and Washington.

This overheating might be described as more people trying to get into a city than its housing base and infrastructure can absorb. Result: skyscraper-high living costs, hideous commutes and wretched lives for those on the economic bottom rung. High rents and homelessness go together.

I'm more persuaded that the decision has been made more to suit Bezos and his executives than to snare talent. Washington is the site of one of the Bezos's mansions and he owns The Washington Post. New York has always had special appeal to the ultra-rich: Wall Street and the gilded social set.

Palo Alto, in California’s Silicon Valley, is white-hot in terms of desirability for high-tech jobs. But it was underdeveloped 45 years ago when a visionary scientist, Chauncey Starr, established the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) there. Starr told me he chose the location not because of the talent pool, but because he wanted the independence he feared he wouldn’t get in a big city, close to the electric companies which funded EPRI. The high-tech talent was yet to move in.

The point here is that it’s not necessary to go to the labor, the labor will come to you. Had Amazon chosen, say Upstate New York or somewhere in Kansas, and hung out a shingle for help, it would’ve poured in: Build and they’ll come.

The great Washington hostess and diplomat Perle Mesta said, “All you have to do to draw a crowd to a Washington party is to hang a lamb chop in the window.” The same goes for labor.

The downside to Washington these days is that its roads and bridges, to say nothing of its troubled subway, are inadequate for the stunning growth it has seen since the late 1960s. It has some of the worst traffic jams anywhere and is said to have overtaken Los Angeles for traffic congestion. As the greater Washington area is split between the District of Columbia, Maryland and Virginia, regional problems are hard to solve and often go unsolved as a result.

New York needs infrastructure spending in the worst way, from the tunnels into Penn Station to the estimated $48 billion the subway needs to modernize. But an increasing amount of the city's capital budget is going to have to be devoted to building barriers against sea rise, particularly in lower Manhattan and to a lesser extent in Brooklyn and Staten Island. Is it a good investment to sink money into any location which is going to have to throw its treasure at Neptune, not improving the rest of the infrastructure?

As someone who lived most of his adult life in Washington, I don’t celebrate its helter-skelter growth, gridlocked roads, potential water shortages or the just-upgraded sewage treatment plant, Blue Plains, which has been known to flood, sending the raw stuff into the Potomac River in big rainstorms.

Virginia and New York, have you bought into a cyber-dream from Amazon which denies reality? You’re paying for a tenant who should pay you for the stress of his buildout.

Prince Bezos, there were so many other pretty feet.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

For Amazon HQ2 pitch, cities needed to promote their REGION

Worcester

-- Photo by Viking 1943

"For small cities like Worcester, bids like this are a missed opportunity not because small cities are not eligible, but because many misunderstand how to sell themselves to large employers. The video that Worcester produced to entice Amazon HQ2 shows off some of the city’s shining stars, such as its medical school, its hockey team and Union Station, but fails to showcase the regional workforce—let alone any other regional assets. When an organization chooses a site, the city name in its address is of less importance than the complete network of resources accessible to the organization from that location. Worcester’s application represented a missed opportunity to leverage the full potential of its regional situation. The failure to act regionally for economic development goes well beyond the Amazon proposal, however.''

From Chris Steele, COO and president (North America) of Investment Consulting Associates, Worcester. One of 238 first round proposals to try to lure Amazon's "Second Headquarters'' that was eliminated.

From "Righting the Wrongs of Amazon,'' in City Lab. To read it, please hit this link.

Katie Parker: Amazon shuts out local businesses

Via OtherWords.org

The billions in tax breaks cities, including Boston, are offering Amazon to host its “HQ2,” Amazon’s bare-knuckled push to squash a business tax in Seattle, and recent strikes for better working conditions in Amazon facilities have all fueled a growing conversation about the retail behemoth’s toll on communities.

But one element of Amazon’s business strategy has fallen under the radar, and this one could really bite where you live: its bid to dominate local government purchasing.

In January 2017, Amazon won a contract with U.S. Communities, a purchasing cooperative made up of government agencies, school districts and other public or nonprofit agencies. The cooperative wields the heft of its more than 55,000 members to negotiate better prices. With this contract, they can now opt to buy their goods through Amazon Business, which advertises greater product selection, free shipping, and pricing discounts.

While the contract is a big boon for Amazon — a potential for $5.5 billion in sales over 11 years — recent analysis from the Institute for Local Self Reliance (ILSR) seriously questions how good a deal the public is getting out of this.

For one thing, the Amazon contract lacks the pricing protections that are usually standard in public procurement. Rather than relying on a catalog of fixed prices, governments are at the whim of Amazon’s dynamic pricing model, much like the “surge pricing” of ride-sharing services.

The Amazon contract also makes it harder for agencies to buy from local vendors. ILSR notes that while local businesses can join Amazon’s Marketplace to compete for U.S. Communities contracting opportunities, Amazon takes a 15 percent cut. That’s enough, given the already thin margins of public procurement, to push many local businesses out of the running.

For the 1,500 members that have signed onto this contract so far, that means a significant missed opportunity to help their local economies thrive. The good news is that a growing number of governments and nonprofits are realizing that getting the lowest bid isn’t the same as getting the best deal.

Local governments spend money every day. They can use that spending to build up local businesses, create jobs for residents, and grow their tax base, something impossible to do with Amazon’s virtual footprint. This purchasing strategy is more efficient, too: Dollars spent at independent local businesses recirculate at a greater rate than money spent at national chains, creating a multiplier effect.

By shifting their everyday spending, city governments from Phoenix to New Orleans are joining hospitals, universities, and other anchor institutions to spark inclusive economic growth.

Cleveland is a great example. There, local anchor institutions like the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals helped launch Evergreen Cooperatives, a network of worker-owned businesses established to provide some of the goods and services these institutions routinely need, such as laundry services and food.

The businesses have an explicit goal of hiring local residents facing barriers to employment, and the cooperative structure gives these workers opportunities to participate in decision-making and build wealth through profit-sharing. Evergreen Cooperatives employs more 220 residents and is growing.

Local governments weighing whether to sign on to Amazon’s marketplace should consider this growing movement around inclusive, local procurement. Instead of being lured by Amazon’s come-on of lowest-price promises, stewards of local tax dollars should ask what would bring the best value for their communities.

Instead of going into Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos’s deepening pockets, the money they spend on goods and services should help everyday residents build wealth.

Katie Parker is a research associate at the Democracy Collaborative with a specialty in how health care institutions can support inclusive economic development.

Executive challenge

Atul Gawande, M.D.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

Atul Gawande, M.D., is a fine surgeon, writer, charming public speaker and teacher who became famous writing about the extreme inequities of health-care provision and cost in America. His main statistical tools were developed by the Dartmouth (College) Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice.

Now he has been tapped to be CEO of a still somewhat mysterious health-care venture formed by the far-too-big Amazon, giant conglomerate Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan, the behemoth bank. The companies haven’t yet presented a specific plan for the new nonprofit enterprise, which hasn’t even been named yet. But the main mission is to cut health-care costs for employers.

The good economic news for New England is that this outfit, which I suppose could become very big itself, will be based in Boston.

"I have devoted my public health career to building scalable solutions for better healthcare delivery that are saving lives, reducing suffering, and eliminating wasteful spending both in the U.S. and across the world. Now I have the backing of these remarkable organizations to pursue this mission with even greater impact for more than a million people {who work for the three companies}, and in doing so incubate better models of care for all. This work will take time but must be done. The system is broken, and better is possible," Gawande said.

The system is indeed broken, but can this rock star run a very large organization?

Good news for brick and mortar

Vacant mall in Arizona, emptied by Amazon.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling (South Dakota v. Wayfair) that Internet retailers be made to collect sales taxes in states where they have no physical presence is good news for what’s left of physical stores and downtowns in many places. Because of earlier legal actions, Rhode Island and Massachusetts are unlikely to be affected much by the ruling.

The Government Accountability Office says that states were already collecting about 75 percent of the potential taxes from online purchases. Still, the part not being taxed could be as much as $13 billion a year nationally.

It has been unfair that a god-awful 1992 ruling let online retailers based far away from most of their consumers avoid paying the local and state sales taxes needed to help pay for public services while stores that directly served local customers and employed local people have had to levy these taxes, of course making their prices less competitive.

Kudos to the 40 states and the Trump administration for suing to overturn a ruling that both violated states’ rights and made for a very unlevel playing field for retailers.

Jim Hightower: Trump's bid to use Postal Service to hit Amazon may backfire big time

Photo by Chensiyuan

Close up of the James A. Farley Post Office, in Manhattan. Read the inscription over the columns: "Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds''

Via OtherWords.org

The U.S. Postal Service has 30,000 outlets serving every part of America. It employs 630,000 people in good middle-class jobs. And it proudly delivers letters and packages clear across the country for a pittance.

It’s a jewel of public-service excellence. Therefore, it must be destroyed.

Such is the fevered logic of laissez-faire-headed corporate supremists like the billionaire Koch brothers and the right-wing politicians who serve them.

This malevolent gang of wrecking-ball privatizers includes such prominent Trumpsters as Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin (a former Wall Street huckster from Goldman Sachs), and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney (a former corporate-hugging Congress critter from South Carolina).

Both were involved in setting up Trump’s shiny new task force to remake our U.S. Postal Service. It’s like asking two foxes to remodel the hen house.

Trump himself merely wanted to take a slap at his political enemy, Amazon chief Jeff Bezos, by jacking up the prices the Postal Service charges to deliver Amazon’s packages. The cabal of far-right corporatizers, however, saw Trump’s temper tantrum as a golden opportunity to go after the Postal Service itself.

Trump complained about the Postal Service not charging Amazon enough for mailing packages. But instead of simply addressing the matter, the task force was trumped-up with an open-ended mandate to evaluate, dissect, and “restructure” the people’s mail service — including carving it up and selling off the parts.

Who’d buy the pieces? For-profit shippers like FedEx, of course. But here’s some serious irony for you: The one outfit with the cash and clout to buy our nation’s whole postal infrastructure and turn it into a monstrous corporate monopoly is none other than… Amazon itself.

I’d prefer my neighborhood post office, thanks. To help stop this sellout, become part of the Grand Alliance to Save Our Public Postal Service: www.AGrandAlliance.org.

Jim Hightower, an OtherWords columnist, is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker. He’s also editor of the populist newsletter, The Hightower Lowdown.

Would Amazon help improve the MBTA?

In Boston's Seaport District, a candidate for Amazon's "Second Headquarters.''

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

With the announcement that Amazon will hire at least 2,000 more people for its Boston operations – and maybe 50,000 more there if it chooses the city for its “Second Headquarters’’ – it’s nice to know that the online mega-retailer has been talking with people in candidate cities about affordable housing and traffic/transit issues that would be raised by so many new people.

In the case of Boston, have the city and company discussed, for example, Amazon helping to pay for the additional MBTA service needed if the company builds the Second Headquarters there, and helping to finance a lot of new housing to limit the rise in living costs in what is one of America’s most expensive places? Considering the huge tax incentives offered in order to lure the company, those questions are fair.

Whole Foods centralizes away the local

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

GoLocal’s March 28 story headlined “Amazon Is Slashing Jobs at Whole Foods in New England Region’’ is an unsettling sign of the times. The story was instigated by a Business Insider article that said: “Whole Foods is slashing regional and in-store marketing and graphic-design jobs in its latest push to centralize operations, say people with knowledge of the matter….It’s not clear exactly how many jobs will be affected….”

GoLocal reports that “the impact locally is that the hand-drawn blackboard signage will disappear and local advertising promotions with {nonprofit} community organizations may go away.’’’ On the East Side of Providence there are two Whole Foods stores and a somewhat similar high-end supermarket called Eastside Marketplace, formerly locally owned but now owned by Ahold, a Dutch company but which heavily promotes local ties. Will Amazon/Whole Foods’ centralizing drive push customers there?

(Trump is correct to say that Amazon has too much power, although he may be mostly driven by his fear and hatred of The Washington Post, which is owned by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos.)

For Greenfield storeowners, Amazon much tougher foe than Walmart

Greenfield in 1917, around its commercial heyday.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

'The Atlantic had a good article (“A Small Town Kept Walmart Out. Now It Faces Amazon,’’ March 2) about Greenfield, a town in western Massachusetts.

Greenfield has managed to keep big-box retailers out of town in order to preserve locally owned stores. But now local store owners and consumers who want to keep them are fighting a bigger enemy – Amazon. The behemoth online retailer offers a convenience that’s very difficult to compete against. Alana Semuels writes:

“Greenfield and other towns across New England are learning that while they might have been able to keep out big-box stores through zoning changes and old-fashioned advocacy, there’s not much they can do about consumers’ shift to e-commerce. They can’t physically keep out e-commerce stores—which don’t have a physical presence in towns that residents could push back against—and they certainly can’t restrict residents’ Internet access. ‘It’s one thing for me to try and fight over land use in the town I live in, or in somebody else's town,’ {local leading} big-box foe {Al} Norman told me, ‘But e-shopping creates a real problem for activists, because on some level, shopping online is a choice people make, and it’s hard to intrude yourself in that.”’

Beyond the demise of local business that keep much of their revenues in their area, there’s a hollowing out of local civil society as people have fewer opportunities to meet in local stores; there are fewer of them as more and more folks order more and more products from home or office. As the Internet society heads toward its fourth decade, we’ll need to find different ways to encourage locals to meet and to participate in their community other than, say, joining AA.

To read The Atlantic’s article, please hit this link: