William Morgan: Public art — banality and grandeur

Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo commissioned a poster that would honor the dedication, sacrifice and nobility of medical workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

That the Sheppard Fairey poster, entitled "Rhode Island Angel of Hope and Strength," has been maligned by Republicans, who see it as "an image of Communist propaganda,’’ is less surprising than that it was commissioned by the state's canny chief executive.

Workers Monument in front of the Soviet Pavilion at the 1937 Paris Expo

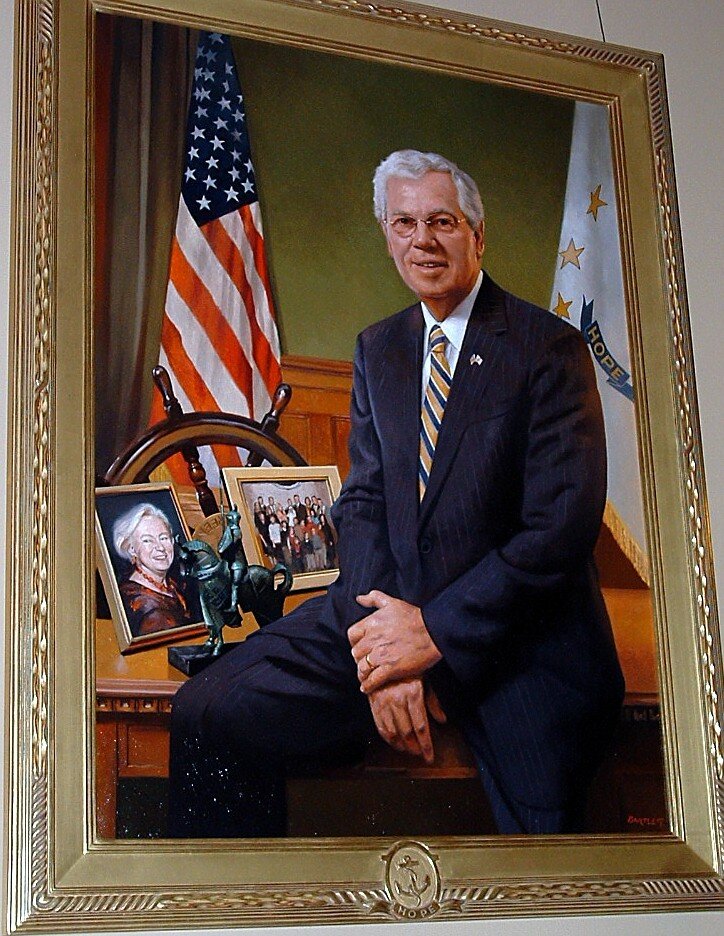

State-sponsored art is rarely memorable, whether a monument to heroes of the Soviet Union or an official presidential portrait (remember the 1965 painting of Lyndon Johnson by Peter Hurd, which LBJ declared "the ugliest damn thing" he'd ever seen). Our postage stamps and coinage are generally nothing to write home about either.

Official portrait of former Rhode Island Gov. Donald Carcieri, which is so realistic that it looks like a photo; the various trappings of office and private life are displayed, as if the man alone were not enough.

Rhode Island School of Design alumnus Fairey is best known for his now iconic 2008 Obama campaign poster, simply labeled HOPE. The Rhode Island Angel's graphic style comes from a long tradition of jingoistic American posters, particularly those from World War I. (“Hope” is the official Rhode Island motto.)

1918 War Bonds poster.

Our COVID-19 angel is pretty tame, especially compared to the public art produced by totalitarian regimes. Both Fascists and Communists almost always revert to the same sort of school textbook realism.

The similarity of different totalitarian regimes' art: Hitler and Stalin as benign fatherly figures.

The issue here is not really one of a partisan polemic (workers of all political stripes wear similar jackets and caps) but the unfortunate tendency of governments to support a flaccid realism.

Irish Famine Memorial in downtown Providence is a tribute to banality – the most simplistic imagery.

— Photo by William Morgan

It may be that government-supported public art, particularly statuary, is oxymoronic. But if we are going to have it, it needs to rise above triteness — for example, of the proposed Dwight Eisenhower monument in Washington — and at least aim for something noble or transcendent.

Proposed statuary for the Eisenhower Memorial in Washington. This D-Day tableau is modeled after a photograph, but this lacks that famous image's immediacy and poignancy.

Red Army Memorial in Sofia, Bulgaria. This has a lot more life than the proposed Eisenhower statute; It’s Soviet Realism at its powerful best.

The curse of such memorials is a sense of literalness, although we get some credit for quickly abandoning the European precedent of portraying our leaders in classical garb.

George Washington in the North Carolina Capitol, by the Italian neoclassical sculptor, Antonio Canova, 1821.

— Photo by William Morgan

It seems unlikely that the sort of politico that conflates flag waving with patriotism will actively encourage any sort of abstraction, as so unlikely but did brilliantly happen with the Vietnam Memorial in Washington.

In an age of all kinds of visual media, perhaps it is time to search for more eloquent and sophisticated expressions of commemoration and grief.

Until that time, we can remember the golden age of public art in this country, the period from the Civil War (which demanded a lot of statuary) to the Great War.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Shaw Memorial, Boston, 1884-97.

— Photo by William Morgan

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, arguably the greatest sculptor whom American has produced, understood the difference between verisimilitude and a powerful naturalism. Saint-Gaudens's monument to Col. Robert Gould Shaw and the black soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment opposite the State House in Boston remains one of the most moving works of American art.

Shaw Memorial, detail.

— Photo by William Morgan

Saint-Gaudens also designed the so-called "double eagle" $20 gold piece at the behest of his friend Theodore Roosevelt. Liberty depicted on the coin – and soaring above Colonel Shaw – is the distant ancestor of the Rhode Island Angel of Hope.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architecture writer. His next book, Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter, will be published by Princeton Architectural Press this autumn.