Llewellyn King: How over-complexity might bring down electricity and other key systems

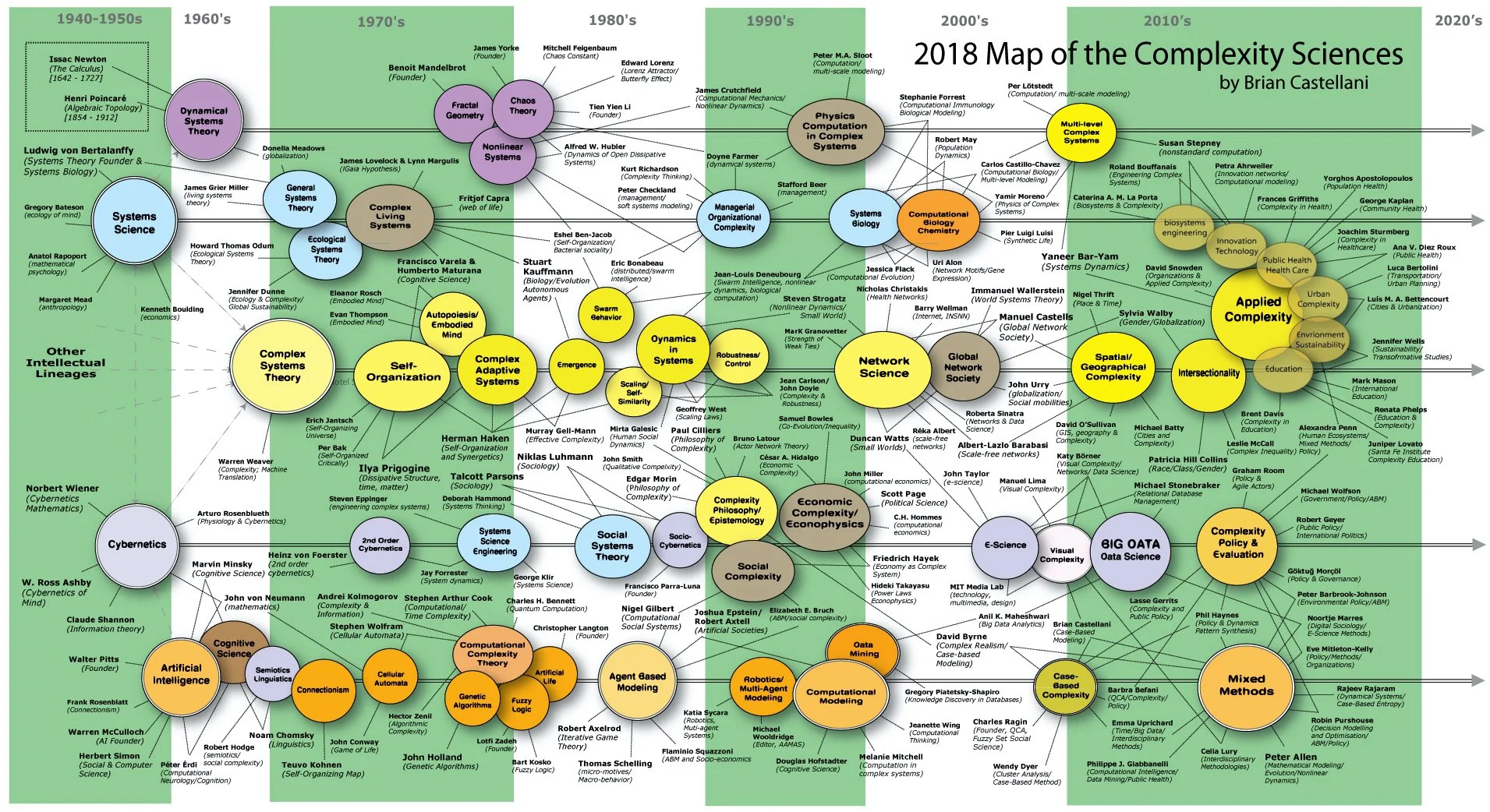

A perspective on the development of complexity science.

Graphic by Brian Castellani

Has the Internet of things — the vast, interconnected, computer-centered ecosystem of today — reached a point where it is so complex, so multilayered, has so many architects, and has so many national interests embedded in it that it has become a threat to itself?

Will the electric grid, the financial system or the air-traffic control apparatus implode not by the hand of a malicious hacker but because the system — which is now systems of systems — has become the most subtle threat it faces?

Worse, as the speed of telephony increases with 5G, will that speed up the system implosion with devastating consequences?

Will this technological meltdown be triggered from within by a long-forgotten piece of code, a failed sensor or inferior products in vital, load-bearing points in this system?

This kind of disaster from complexity is known as “emergent behavior.” Remember that concept. Likely, you will hear a lot about it going forward.

Emergent behavior is what happens when various objects or substances come together and trigger a reaction that can’t be predicted, nor can the trigger be predetermined.

Robert Gardner, founder and principal at New World Technology Partners and a National Security Agency consultant, tells me that the computer ecosystem is highly subject to emergent behavior in the so-called complex, adaptive system of systems which is today’s cyberworld. It is a world which has been built over time with new layers of complexity added willy-nilly as computing, and what has been asked of it, has become a huge, impregnable structure, beyond the reach of its present-day architects and minders, including cybersecurity aficionados.

In at The Creation

Gardner, to my mind, is worth listening to because he was, if you will, in at the beginning. At least, he was on hand and worked on the computer evolution, starting in the 1970s when he helped build the first supercomputers and has consulted with various national laboratories, including Lawrence Livermore and Los Alamos. He has also played a key role in the development of today’s super-sophisticated financial computing infrastructure, known as “fintech.”

Gardner says of emergent behaviors in complex systems, “They can’t be predicted by examining individual components of a system as they are produced by the system as a whole — facilitating a perfect storm that conspires to produce catastrophe.”

Complexity is the new adversary, he says of these huge, virtual systems of systems.

Gardner adds, “The complexity adversary does not require outside assistance; it can be summoned by minor user, environmental or equipment failures, or timing instabilities in the ordinary operation of a system.

“Current threat detection software does not seek or detect these system conditions, leaving them highly vulnerable.”

Gardner cites two examples where the system failed itself. The first example is when a tree branch that fell on a power line in Ohio set in motion a blackout across Michigan, New York and much of Canada in 2003. The system became the problem: It went berserk, and 50 million people lost power.

The second example is how something called “counter-party risk” sped the demise of Lehman Brothers, the Wall Street colossus. That was when a single default embedded in the system initiated the implosion of the whole structure.

No Nefarious Actors

Of these, Gardner says, “There were no nefarious actors to defend against; the complex, heterogeneous nature of the systems themselves led to emergent behaviors.”

Going forward, the best practices in cyber hygiene won’t defend against catastrophe. The entwined systems are their own enemy. Utilities take note.

And the danger may get worse, according to Gardner.

The villain is 5G: the super-fast phone and data system now being deployed across the country. It will come in what are called “slices,” but for that you can read stages.

. Slice one is what is being built out now: It is faster than today’s 4G, which is what phones and data use currently. It features mobile broadband.

· Slice two, called “machine to machine,” is faster yet.

· Slice three will move vast quantities of data at astounding speeds which, if the data is damaging to the system and has occurred at an unidentifiable location, represents a threat to a whole tranche of human activity.

Self-destroying machines will be unstoppable when they have 5G slice three to speed bad information throughout their system and connected systems. Tech Armageddon.

Llewellyn King, a veteran columnist, editor, publisher and international energy consultant, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of "White House Chronicle" on PBS.

Read this column on:

White House Chronicle

Forbes