Frank Carini: Connecticut River ecosystem is much healthier these days but still threatened

— American Rivers map

Text from ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A recuperating natural world borders and lives in the only major river in the Northeast without a large port, harbor or urban area at its mouth. It provides drinking water to millions and supports recreational uses and important fisheries.

But 57 years ago actress Katharine Hepburn called the Connecticut River “the world’s most beautifully landscaped cesspool.”

By the mid-1960s, the longest river in New England, at 410 miles, had served as the region’s industrial- and human-waste sewer for more than a century. It had been unsafe for recreational use since the early 1900s, according to Ellsworth Grant’s 2006 book , Connecticut Disasters.

Hartford’s Park River, also known as Hog River, a tributary that used to deliver waste into the Connecticut River, was buried in the 1940s, in large part because it was so polluted, according to Walter Woodward, Connecticut’s state historian from 2004 until his retirement this year.

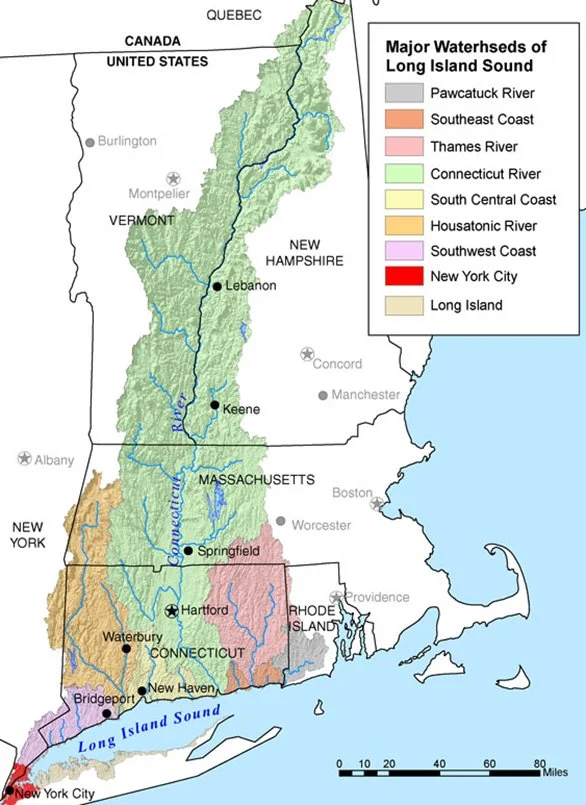

The Connecticut River deposits silt as it flows into Long Island Sound.

In 1965, Hepburn, who had a home in the Fenwick section of Old Saybrook at the mouth of the river, narrated a half-hour documentary called The Long Tidal River about the polluting of the Connecticut River. The title was taken from the Algonquian peoples of southern New England who have called the Connecticut River the “long tidal river” for hundreds of years.

The Hepburn-narrated film reportedly helped spark an environmental movement in New England that called for building more wastewater- treatment facilities and placing tighter restrictions on polluting industries. The film and its money quote also prompted state and federal government to adopt laws to clean up the Connecticut River and many other waterways similarly polluted.

In 1967, the Connecticut Legislature passed a Clean Water Act, and five years later the federal government passed its own Clean Water Act.

“The river was really dirty and polluted. We’ve seen an amazing amount of progress in the last 50 years,” said Kelsey Wentling, the Massachusetts river steward for the Connecticut River Conservancy (CRC). “I’ve spoken with people who never touched or came near it as kids but now swim and fish in the river.”

Drift boat fishing guide working the Connecticut river near Colebrook, N.H., in the steam’s upper riches during the brief summer up there.

— Photo by Mike Cline

More than a half-century of increased awareness and pollution-control efforts have transformed the Connecticut River — which flows through four of New England’s six states, from the Canadian border to Long Island Sound — from a sewer system to a national symbol of environmental restoration. The river and its tributaries have received several federal designations for their wild and scenic nature and for their importance to the region’s cultural heritage.

The Nature Conservancy has called the river’s estuary “one of the world’s last great places.” The river’s vast watershed — about 77 percent is forested, 9 percent agricultural, 7 percent wetlands, and 7 percent developed, according to the Army Corps of Engineers — is home to federally threatened and endangered species such as the piping plover, the puritan tiger beetle, dwarf wedgemussel, Jesup’s milk-vetch, and northeastern bulrush. Its also the critical lifeline for the 40,000-acre Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge.

In 1997, the Connecticut River was designated an “American Heritage River” in recognition of its “distinctive natural, economic, agricultural, scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational qualities.”

Fifteen years later, in 2012, the U.S. Department of the Interior named it America’s first National Blueway. The program, however, designed to recognize conservation efforts along the nation’s waterways, was dissolved two years later amid opposition from landowners and politicians who feared that it would lead to increased regulations and possible land seizures. The Connecticut River remains the country’s only National Blueway.

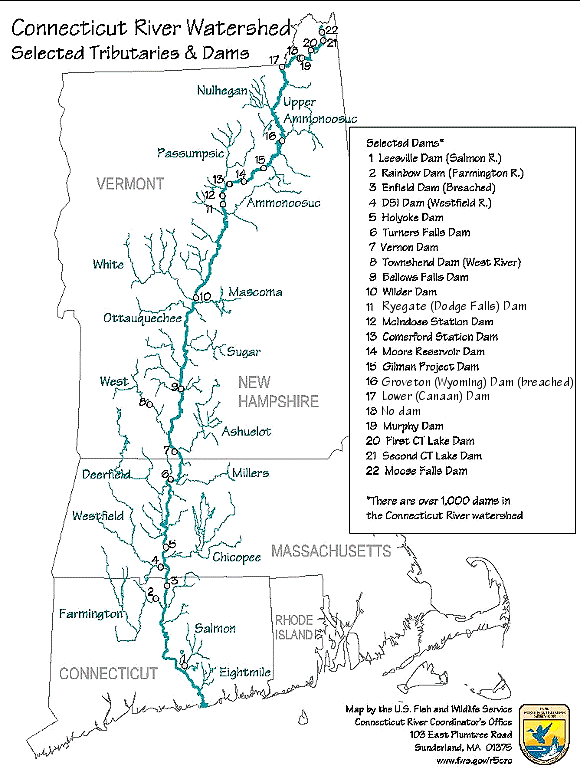

Despite the river’s metamorphosis from dead zone to one swimming with alewife, American and hickory shad, blueback herring, smallmouth bass, striped bass and three species of trout, the Connecticut River still remains among the most extensively dammed rivers in the country. More than a thousand dams dot its tributaries and 16 dams span its mainstem, 12 of which are hydropower projects.

It, like most U.S. waterways, is vulnerable to pollution from stormwater runoff carrying fertilizers, pesticides, agricultural waste, and hydrocarbons. Fish advisories are in place for sections of the river, swimming is discouraged after heavy rains, and the river’s sediment is still plagued by a legacy of contamination.

While farming and logging brought significant ruination to the Connecticut River watershed before the 19th Century, industrialization in the 1800s accelerated the destruction. Industries diverted the natural flow of the river to generate power and dumped all kinds of waste into it.

By the beginning of the 20th Century, agricultural runoff from commercial farming — in particular, the area’s thriving tobacco industry — further polluted the river. By the time that World War II ended, the use of new chemical dyes and pesticides had added to the river’s ruination.

CRC, formerly the Connecticut River Watershed Council, has been addressing these issues since the early 1950s. Last year the Greenfield, Mass.-based nonprofit completed five years of work to improve the health of the Connecticut River and Long Island Sound.

The work was part of a $10 million partnership grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to promote conservation of the Long Island Sound watershed. CRC focused on reducing pollution in the Connecticut River, which contributes about 70 percent of the fresh water to Long Island Sound.

CRC completed 58 river-restoration projects covering more than 180 miles and 60 acres in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont. The projects were designed to help reduce erosion, runoff, and excess nitrogen, which cause low dissolved oxygen levels that threaten fish and other aquatic organisms.

The work included planting trees and shrubs along rivers on agricultural lands to slow runoff and filter pollutants from water before it enters waterways; berm and dam removals that restore natural river flows and decrease erosion during floods; and streambank stabilization to keep soil in place.

One problem that remains, especially in the Connecticut portion of the river, Wentling said is invasive species such as water thyme and water chestnut creating a “monoculture mat” that is crowding out native plants and animals.

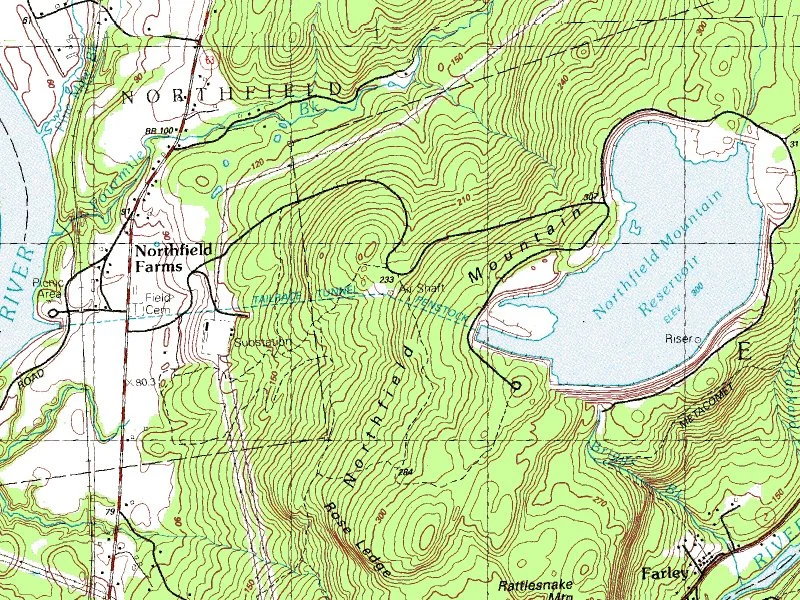

One of the bigger threats — beyond sewage overflows from wastewater- treatment facilities during heavy rains — remaining on the Connecticut River system, or at least a section of it, is FirstLight’s Northfield Mountain Pumped Storage Station, a hydroelectric generating facility and reservoir in Franklin County, Mass. Fossil fuels are used to pump water up to the reservoir on the hill. Wentling said it takes more energy to move the water up than is created when it is released back down. The banked energy in the reservoir is used when energy prices are high or there is a spike in demand.

Besides burning natural gas to create future hydropower, the power plant is “killing” countless fish and other aquatic organisms, according to longtime Connecticut River defender Karl Meyer.

In a Nov. 3 opinion piece published in VTDigger, the Greenfield, Mass., resident wrote, “The Northfield station is the deadliest machine ever installed on New England’s Great River. It sucks in endless streams of the Connecticut’s flow at 15,000 cubic feet per second for hours — the equivalent of eight three-bedroom homes filled with aquatic life every second, inhaling over 28,000 fish houses an hour.”

He noted that American shad are just one of two dozen species exposed to that daily suction. “For those other species, what’s undisputed is none of their millions of untallied eggs, adults and young survive the trip through Northfield either.”

Meyer, who said this problem has been ignored for decades, has been writing about issues affecting the Connecticut River for years. He has concentrated his efforts on the needs of the river’s fish, with a particular concern for American shad and the shortnose sturgeon, an endangered species.

FirstLight’s renewal process for a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) license is expected to begin by the end of the year. Meyer, for one, isn’t happy it has taken four years to get to this point.

“FirstLight now operates the Northfield Mountain Pumped Storage Station via its series of FERC license delay requests while its venture capital shareholders and CEOs profit off an expired 2018 license,” he wrote.

He’s concerned the “license disastrously poised to re-enshrine Northfield’s horrific impacts for decades.”

Wentling said the climate crisis, from drought to bursts of extreme rainfall, is exacerbating the stress that the Connecticut River remains under, and it’s only going to get worse.

Frank Carini is co-founder and senior reporter for ecoRI News.