Alissa Quart: Tech execs should read history

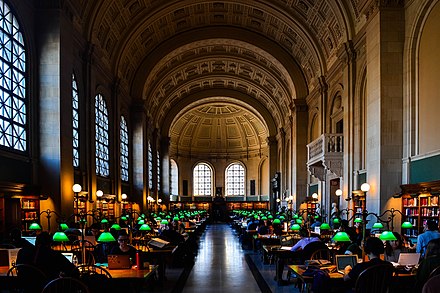

The main reading room of the Boston Public Library

Via OtherWords.org

America’s tech giants are accused of many sins, including invading our privacy and even degrading our democracy. But one other commonality among these masters of the code universe is rarely discussed: Virtually no tech CEOs have a background in the humanities, such as literature and history.

What does it mean to be human? What does it mean to be a citizen? And what are our responsibilities to one another? If their behavior is any guide, tech titans have never thought deeply about any of these questions.

Instead, major social platforms like Facebook simply build fines for privacy violations into their budgeting. Ride-sharing services like Uber underpay their hardworking drivers and offer no benefits. And hate speech runs rampant on all social networks.

If our tech overlords had studied the humanities — rather than just business or computer science — they might have been less likely to treat our data as a commodity to be used for their own purposes. Facebook might not have blithely violated its 2011 privacy consent decree, or stood back when hate speech consumed its platform.

I’m not alone in believing that arts and humanities training could create much better technologists. In a 2018 study, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine called for an integration of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics with these less numerical disciplines.

In designing technology, empathy and other human-scale values are now being championed as well. After all, how can you sell good “user experience” if you know little about the users? And when the robots come for our jobs, human creative intelligence may be one of the only things still needed in the labor market.

One might ask: What are the chances of building a tech unicorn if you studied Chaucer or Weber rather than computer science?

But my argument isn’t that only English majors should run tech incubators, but that our digital masters should find a place in their lives and minds for Plato and Margaret Mead. As a study by psychologists David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano shows, literature makes us better at comprehending other people’s feelings — a useful skill in both a leader and an employee.

If Uber and other gig economy “winners” had studied Dickens or labor history, would they have fought so nastily to maintain that their drivers are “side hustling,” concierge-like contractors with few employment rights?

If executives at Lyft had read Jane Addams’s 20 Years At Hull House, or even a textbook on the basics of maternal biology, would they have celebrated the fact that a driver had to pick up riders after she went into labor, and then Lyft herself to the hospital to give birth?

And if those who insist on creepily long hours from their employees had at least read Marx, they might not snicker so affectionately at the T-shirt slogan “9 to 5 is for the weak.”

Today’s tech jobs — with “nap pods” and campus environments that make it so their workers almost never leave work — evoke Marx’s account of how long work days rob people of their “normal, moral, and physical conditions of development.”

This is part of a broader problem, of course. In 1971, there were fewer than two business majors for every English major in American colleges. As of 2016, it’s more than 8 to 1 and growing.

As T.S. Eliot wrote: “Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?”

Studying the humanities means engaging with what the Romantics called “the sympathetic imagination” — an idea that tech overlords would hopefully direct not just at themselves but also toward other people.

Alissa Quart is executive director of the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, which produced this piece. It ran first at the San Francisco Chronicle as was adapted for distribution by OtherWords.org.