Don Pesci: ‘Shrouded in silence’

The riderless (caparisoned) horse named "Black Jack" during the departure ceremony as President Kennedy’s body was taken from the U.S., Capitol.

VERNON, Conn.

I had been playing basketball and decided, possibly for the second time in my first year as a student at Western Connecticut State College, to take a shower. Most often I showered at Mrs. Gallagher’s, about three city blocks from the college, where I had been boarding with a roommate, Edward Kennedy, a red-headed Irish pool shark.

Mrs. Gallagher was our sometimes eccentric landlady whose features suggested that she was a stunner as a young lady. She liked Kennedy’s red hair. And he, who could easily wind people around his pinky, joined Mrs. Gallagher for rum toddy once a week before bedtime.

The sky, as I remember it, was overcast, the weather around 38 degrees. The November wind was gentle. Girls were bent over a red convertible, its top down, weeping over the blare of a radio.

“What’s happened?” I asked as I passed them.

“Someone killed Kennedy,” one of the girls said.

Almost whispering to myself, I muttered, “Who would want to kill Ed Kennedy?’

President Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963, the Friday before Thanksgiving that year. Four of us, two close friends and a student I did not know well, left the day after the assassination for Washington, D.C., to pay our respects to the fallen president. We thumbed our way, bearing a large handwritten sign: “Washington DC – Kennedy funeral.”

We made the trek in three rides, astounding I thought at the time, but then our sign was an emotional passport. The assassination had scrambled everyone’s brains and hearts. And on this day, the wounded heart of the nation lay open, dissolving all the usual political oppositional chatter.

Our last chauffeurs were two young men, both taciturn Southerners who were in need of gasoline money to make their way home.

“We don’t have much, but we can give you what we can spare.”

We gave the two $10 and were let off late at night at Union Station, a short walk from the Capitol. All four of us fell asleep on the hard benches.

Early in the morning, I felt the soft tap of a baton on the sole of my shoe, and a gentle voice peeled the sleep from my eyes.

“Time to get up boys and be about your business,” the police officer said.

Even early in the morning, the streets were lined, number crunchers later said, with upwards of a million people, some having waited patiently – silently – for 10 hours and more.

The silence suited me. During my four years in Danbury, unable to shake off a sometimes debilitating shyness, I had found comfort in the well-stocked library of Danbury State College, renamed during my time there Western Connecticut State University, writing from time to time for Conatus, the university’s literary magazine – nothing political. The political writing came much later, during the early 1980’s.

My literature professor asked me on my return from D.C. whether I had planned to write anything about the Kennedy assassination. I declined with a sharp “No.”

He would never have understood my reasoning, if one could call it reasoning.

I did not want to shatter the muffled silence – holy, in its own way – that touched everything during the ensuing days and weeks that followed. I just could not join in the general chatter, which I felt was, in some sense, obscene, because much of it was self-glorifying nonsense.

My mother, I recalled, had voted for Kennedy after the Kennedy-Nixon debates, in September 1960. My father, who was one of a handful of Republicans in Windsor Locks, Conn., a Democratic Party bastion, was astonished by this, and asked her at the supper table, where delicate matters were discussed, “Why on earth did you vote for a Democrat?”

“I found Nixon’s eyes shifty,” she said.

This revelation was followed by a muffled silence.

I married my wife, Andree, during my last year at Danbury. On a visit to her house in Fairfield, Conn., I found a framed picture of Kennedy near the family organ adorned by palms, blessed during Palm Sunday, fresh and smelling like the incense-drenched church in which we were married.

That day in Washington, we stood silent as horses’ hooves beat a tattoo on streets. First came the coffin born by white horses, wintry plums of breath streaming from the horses’ wide nostrils, these followed by “Black Jack’’, a riderless horse, boots strapped backwards covering its stirrups, then the crowd. All was shrouded in a holy silence in which, if one was paying close attention, one might hear the voice of Blaise Pascal saying, “In the end, they throw a little dirt on you, and everyone walks away. But there is One who will not walk away.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

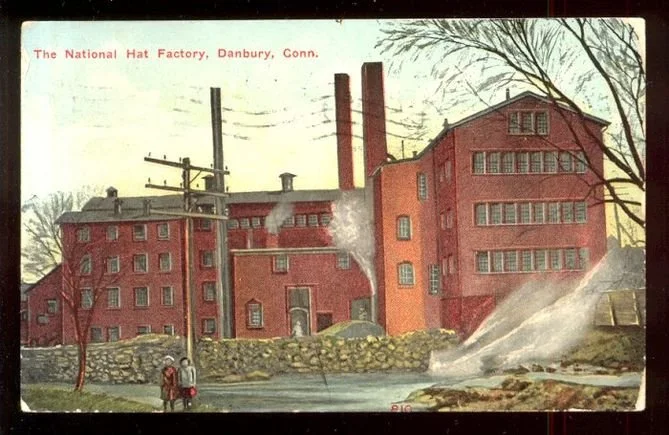

National Hat Co. factory in Danbury. For many decades Danbury was famous as a center for hat making. Sadly, mercury was used for making the felt that made up most of the hats, poisoning many workers and polluting the Still River. Connecticut didn’t ban this use of mercury until 1937.