Stuart Vyse: Looking for the light in our inner worlds

This essay first ran in New England Diary on Nov. 19, 2017

I used to dread the descent into darkness in late autumn. There comes a time when, well before you get up from your desk to go home, the world outside your window is as black as midnight. It is barely five o'clock in the afternoon, but there is no natural light left to guide you home or illuminate your evening activities. It is too early to sleep, and yet you must push against the blackness to stay alert and awake. Eventually here in the northern latitudes, the reluctant cold-weather sun manages only the briefest appearance in the middle of the day before slipping away behind a mid-afternoon sunset.

It is easy to feel depressed by the weight of light's absence -- by a life that sometimes feels subterranean and nightmarish. But I have come to welcome the change of year. Seasons mark the time. All seasons. They tell us we have been here before, and if all goes well, we will be here again. The changing light and landscape conjure memories: of jumping in piles of leaves, of a beautiful ice storm, or of a frozen lemonade drunk in the car on the way home from the beach.

Thanks to a quirk of our psychology, we tend to suppress the unpleasantness of the past, and our memories are often warm and nostalgic, no matter what the temperament of those distant times.

I have grown to appreciate the brightness hidden within the winter black. There are the familiar holidays clustered around winter solstice -- that shortest day when the darkness begins to slowly pull back its veil. These celebrations are filled with candles and lights and burning fires that show the way to the equinox and warm weather beyond.

Although there is less light around the solstice, the light there is is of a special quality. The winter sun hurls its shafts through the window at a flatter angle, crashing them against the floors and walls. During the season we are inside the most, the sun finds a way to light the room as brilliantly as possible, and then too soon it is gone.

But, for me, the great hidden light of the dark season can only be seen from outside. As you walk the sidewalks or drive through your neighborhood at night, the houses are lit from inside out, throwing great yellow beams onto the lawn. We never know what goes on in other people's homes, and sometimes it is better that way. But from a safe distance away I imagine families together -- not avoiding the darkness outside, but drawn to the light and heat inside. Making a warm world together within the wintry one beyond the walls.

Perhaps it is wishful thinking, but I like to imagine that, for those of us who live where there are seasons, this cycle serves an important purpose. I want to believe that during this time of year when the sun recedes beyond the horizon, nature compels us to go home. Like bears returning to their caves, we come inside -- not to hibernate -- but to awaken to a different source of illumination.

The spinning Earth tells us to spend a little less time outside and a little more with family and friends -- and, perhaps, a little more in the smaller spaces of our inner worlds. Ideally, when the warm weather returns, we emerge restored, with a new appreciation of the world outside.

Of course, life is not always ideal. Sometimes the sense of cold-weather fellowship is more an idea -- a memory -- than a reality. Easier seen from outside on the sidewalk than from inside the house. But even then, the blackness of winter provides the perfect backdrop for imagination and reexamination. As we are forced indoors we have a chance to look inward, too. A chance to seek a private incandescence to guide us through the dark season.

Perhaps this is part of what the winter holidays are supposed to do. Show us a different source of light; encourage us to look inward as we go inside; and give us hope that the spring will come again.

The gathering shadows of autumn are often difficult to accept. The hope of longer days seems so far away. But I have come to understand that, when darkness comes, we need not rue the absent sun. It is simply time to go inside and make our own light.

Stuart Vyse is a psychologist and writer living in Stonington, Conn., where he lives in the old Steamboat Hotel, about which he wrote an eponymous book.

The publisher explains:

“From 1837 to 1900, the tiny borough of Stonington, Connecticut, was a major transportation hub on the route between New York and Boston. Steamboats leaving Manhattan followed Long Island Sound to Stonington Harbor, where passengers boarded trains for the rest of the journey to Providence or Boston. Stonington’s Steamboat Hotel, built 1838 near the piers and railroad yard, was home to saloons, restaurants, a pool hall, a cigar shop, a tailor and a barber shop. Merchants, hotel keepers and saloon workers passed through the building, each with their own unique story. Many of them were immigrants or first-generation Americans, and they are a window on a late nineteenth-century class of merchants and service workers. Join local author Stuart Vyse as he reveals a lively portrait of remarkable harmony in a small village that was far more diverse than it is today.’’

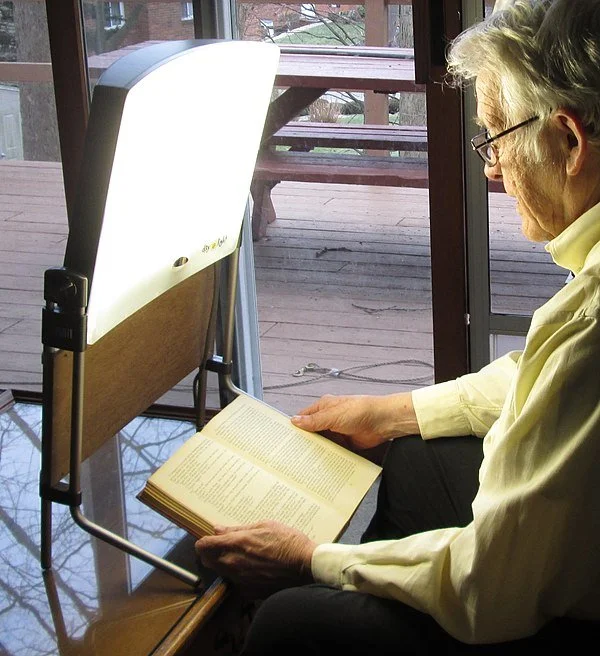

Bright light therapy is a common treatment for seasonal affective disorder, which is associated with diminished sunlight from fall into the winter.