William Morgan: My statuary saga in tense times

Roger Williams Memorial, Prospect Terrace, Providence

— Photo by William Morgan

In Rhode Island, we might soon exorcise half of the official name of our state as a symbol of solidarity with Black Lives Matter. The state’s official name is State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. As we are removing statues that some find offensive, maybe we should take a look at some of our sculptural monuments here in Providence.

Providence Plantations was the name of Roger Williams’s colony, founded in 1636. He was one the most inclusive of all of America’s founding fathers. But the word “Plantations’’ holds unwholesome associations with the Antebellum South, echoes of Gone with the Wind and of America’s original sin of slavery.

Despite being beloved by many Native Americans and having translated the Bible into Narragansett, Williams made an unfortunate choice of nomenclature almost 400 years ago. Do we need to consider taking down images of Williams?

The statue (above) of Roger Williams overlooking the city from Prospect Terrace was the result of a competition during the 1930s, won by architect Ralph Walker and sculptor Leo Friedlander. In the spirit of those times, the composition looks like something that Mussolini ordered over the telephone.

Frédéric Bartholdi’s handsome rendition of Columbus is a version of the eponymous statue exhibited at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

— CareerShift.com

Already gone from its South Providence neighborhood, the Christopher Columbus statue above has met the fate of many monuments to the Genoese explorer in the employ of the Kingdom of Spain. A brave sailor, Columbus opened the Western Hemisphere to development, and thus to the exploitation of native peoples.

For generations, Columbus Day was the celebration day for Italian-Americans, a long-vilified immigrant group. But today do we need to consider changing the names of Columbia University, Columbus, Ohio, and the South American country of Colombia, not to mention Venezuela, which the intrepid navigator named?

And what might we do with the Providence statues of Dante, Garibaldi and Marconi? Statues put up to honor the great Florentine poet, the George Washington of Italy and the inventor of the radio would seem fairly uncontroversial, but you never know what you might in their histories….

And not just Italians. Are there any statues of Portuguese explorers in Rhode Island? Like the retired Mississippi flag, the Portuguese banner is surely a symbol of brutal colonialism in Latin America, Asia and Africa. Right?

As for Rhode Island’s outsized role in the Civil War, our monuments honoring Union leaders should be above reproach.

Nationally famous sculptors Randolph Rogers and Launt Thompson fashioned the Soldiers and Sailors Monument in front of Providence City Hall and the Burnside equestrian statue, respectively.

Ambrose Burnside statue, Kennedy Plaza, 1887.

Now that Theodore Roosevelt is being literally knocked from his pedestal, Spanish-American War monuments will probably soon follow. After all, the war with Spain brought American into its first big imperialist venture, after our seizure of much of Mexico in the 1840’s, as “liberators’’ of Cuba and the Philippines.

“The Hiker,’’ in Kennedy Plaza, was put up by the National Association of Spanish War Veterans, and therefore probably should go – except that its creator was a pioneering woman sculptor, Theodora Kitson. Score one for women’s rights.

“The Hiker, ‘‘ in Kennedy Plaza, Providence, by Theodora Kitson

— Photo by William Morgan

The less-than-ramrod-straight trooper in Providence’s North Burial Ground, commemorating “Citizens who served in the War with Spain, the Philippine Insurrection and the China Relief Expedition,’’ should also remain unmolested. While this soldier’s fey demeanor was probably unremarked upon in 1904, it deserves special protection.

Spanish-American War soldier, by Allen Newman, North Burial Ground, Providence

— Photo by William Morgan

Arguably, the most artistically significant sculpture in Providence adorns the entrance to the Union Trust Building, on Dorrance Street. “The Puritan and the Indian’’ is the work of America’s second-greatest sculptor (Augustus Saint-Gaudens was the greatest), Daniel Chester French, whose best-known work is the statue of Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington.

“The Indian and the Puritan,” by Daniel Chester French

— Photo by William Morgan

French was clearly inspired by Michelangelo’s tomb figures in the Medici Chapel, in Florence. Yet “The Indian and the Puritan,” despite their beautifully idealized physiques, represent stereotypes that might be offensive. In an unequal competition of assets, the Puritan rests on a library of scholarly tomes, while the “noble savage’’ has snowshoes and a pipe.

Brown University offers the city’s richest concentration of public sculpture, ranging from the naturalism of its recent life-size (yet curiously genital-less) Kodiak bear, by British artist Nick Bibby, to the rather traditional academic copies of the über-imperialist Roman Emperors Julius Caesar and Marcus Aurelius.

Marcus Aurelius, on the Brown University campus

— Photo by William Morgan

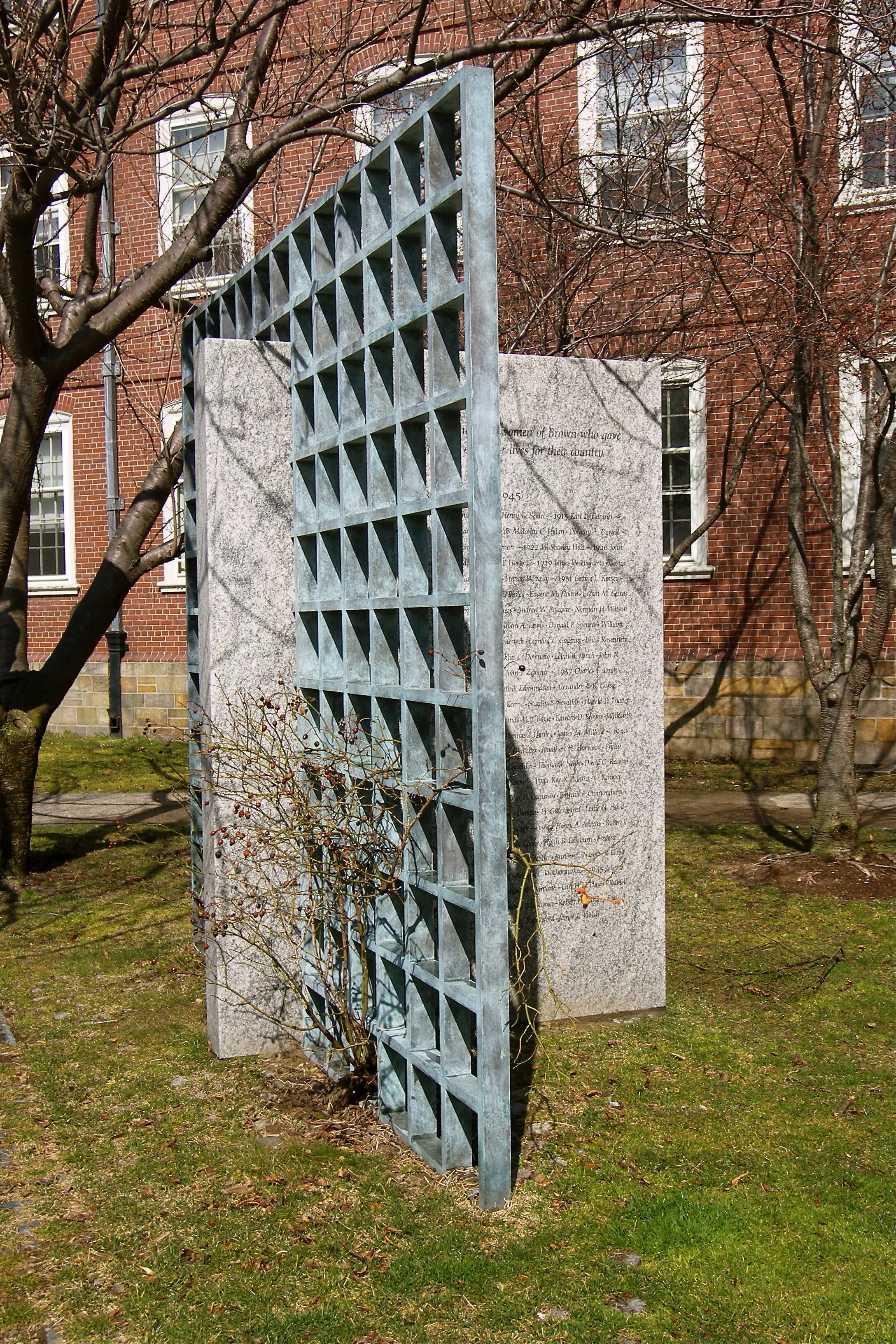

Not far from Marcus Aurelius is the Brown memorial to university alumni who died in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. After the bombast of the Civil War memorials, Richard Fleishner’s modest granite slab and bronze lattice is elegiac and refreshingly timeless.

Brown war memorial by Providence artist Richard Fleishner

— Photo by William Morgan

As with its new architecture, Brown seems to hire important designers and then is not quite sure what to do with them. We can say the same of the placement of some of the three-dimensional artwork they acquire.

Brown commissioned Maya Lin, creator of the hugely influential Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, to do a piece for the university. Instead of one of Lin’s adventurous land sculptures, Brown preferred something less bold and controversial. Lin’s slab, inscribed with a map of Narragansett Bay, is disappointing and poorly placed.

“Under the Laurentide,’’ by Maya Lin, on the Brown campus

— Photo by William Morgan

The thoroughly inappropriate placement on Brown’s College Green also lessens the impact of Brown’s real sculptural prize, “Three-Piece Reclining Figure Number Two,’’ by the great English artist Henry Moore. This is one of six castings of this piece. Moore’s bronze figures were status symbols in the 1970s – it seemed that curators of every museum or university felt they had to have one.

“Three-Piece Reclining Figure,’’ by Henry Moore, at Brown

— Photo by William Morgan

But any Henry Moore, however displayed, is always a welcome treasure. And the Brown gem demonstrates that an abstract piece with a vague-sounding and totally apolitical name can survive decades of cultural storms.

Public art is necessary to defining who we are, and can also be the focus of protest. Revolution is a hallowed Rhode Island tradition, but let us try to maintain our tradition of tolerance as we embrace new visual expressions.

William Morgan, the author of many books, is a Providence-based architectural historian and essayist.