Taking it in

“Recliner” (bronze), by Joy Brown, in her show “The Art of Joy Brown,’’ at the Hotchkiss School’s Tremaine Gallery, Lakeville, Conn., March 25-April 6.

This retrospective traces Brown’s work, from tiny clay figures to clay-headed puppets, to small statues and wall tiles, to the monumental work found in public spaces.

Richard E. Peltier: Now under threat, Clean-Air rules help health and economy

Smog in Los Angeles

From The Conversation (except for photo above)

Richard E. Peltier is a professor of environmental health sciences at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

He receives funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Rio Grande International Science Center.

The Trump administration announced on March 12 that it is “reconsidering” more than 30 air pollution regulations in a series of moves that could impact air quality across the United States.

“Reconsideration” is a term used to review or modify a government regulation. While Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin provided few details, the breadth of the regulations being reconsidered affects all Americans. They include rules that set limits for pollutants that can harm human health, such as ozone, particulate matter and volatile organic carbon.

Zeldin wrote that his deregulation moves would “roll back trillions in regulatory costs and hidden ‘taxes’ on U.S. families.” But that’s only part of the story.

What Zeldin didn’t say is that the economic and health benefits from decades of federal clean air regulations have far outweighed their costs. Some estimates suggest every $1 spent meeting clean air rules has returned $10 in health and economic benefits.

In the early 1970s, thick smog blanketed American cities and acid rain stripped forests bare from the Northeast to the Midwest.

Air pollution wasn’t just a nuisance – it was a public health emergency. But in the decades since, the United States has engineered one of the most successful environmental turnarounds in history.

Thanks to stronger air quality regulations, pollution levels have plummeted, preventing hundreds of thousands of deaths annually. And despite early predictions that these regulations would cripple the economy, the opposite has proven true: The U.S. economy more than doubled in size while pollution fell, showing that clean air and economic growth can – and do – go hand in hand.

The numbers are eye-popping.

An Environmental Protection Agency analysis of the first 20 years of the Clean Air Act, from 1970 to 1990, found the economic benefits of the regulations were about 42 times greater than the costs.

The EPA later estimated that the cost of air quality regulations in the U.S. would be about US$65 billion in 2020, and the benefits, primarily in improved health and increased worker productivity, would be around $2 trillion. Other studies have found similar benefits.

That’s a return of more than 30 to 1, making clean air one of the best investments the country has ever made.

Science-based regulations even the playing field

The turning point came with the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970, which put in place strict rules on pollutants from industry, vehicles and power plants.

These rules targeted key culprits: lead, ozone, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides and particulate matter – substances that contribute to asthma, heart disease and premature deaths. An example was the removal of lead, which can harm the brain and other organs, from gasoline. That single change resulted in far lower levels of lead in people’s blood, including a 70% drop in U.S. children’s blood-lead levels.

Air Quality regulations lowered the amount of lead being used in gasoline, which also resulted in rapidly declining lead concentrations in the average American between 1976-1980. This shows us how effective regulations can be at reducing public health risks to people. USEPA/Environmental Criteria and Assessment Office (1986)

The results have been extraordinary. Since 1980, emissions of six major air pollutants have dropped by 78%, even as the U.S. economy has more than doubled in size. Cities that were once notorious for their thick, choking smog – such as Los Angeles, Houston and Pittsburgh – now see far cleaner air, while lakes and forests devastated by acid rain in the Northeast have rebounded.

Comparison of growth areas and declining emissions, 1970-2023. EPA

And most importantly, lives have been saved. The Clean Air Act requires the EPA to periodically estimate the costs and benefits of air quality regulations. In the most recent estimate, released in 2011, the EPA projected that air quality improvements would prevent over 230,000 premature deaths in 2020. That means fewer heart attacks, fewer emergency room visits for asthma, and more years of healthy life for millions of Americans.

The economic payoff

Critics of air quality regulations have long argued that the regulations are too expensive for businesses and consumers. But the data tell a very different story.

EPA studies have confirmed that clean air regulations improve air quality over time. Other studies have shown that the health benefits greatly outweigh the costs. That pays off for the economy. Fewer illnesses mean lower health care costs, and healthier workers mean higher productivity and fewer missed workdays.

The EPA estimated that for every $1 spent on meeting air quality regulations, the United States received $9 in benefits. A separate study by the non-partisan National Bureau of Economic Research in 2024 estimated that each $1 spent on air pollution regulation brought the U.S. economy at least $10 in benefits. And when considering the long-term impact on human health and climate stability, the return is even greater.

Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles in 1984: Smog was a common problem in the 1970s and 1980s. Ian Dryden/Los Angeles Times/UCLA Archive/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

The next chapter in clean air

The air Americans breathe today is cleaner, much healthier and safer than it was just a few decades ago.

Yet, despite this remarkable progress, air pollution remains a challenge in some parts of the country. Some urban neighborhoods remain stubbornly polluted because of vehicle emissions and industrial pollution. While urban pollution has declined, wildfire smoke has become a larger influence on poor air quality across the nation.

That means the EPA still has work to do.

If the agency works with environmental scientists, public health experts and industry, and fosters honest scientific consensus, it can continue to protect public health while supporting economic growth. At the same time, it can ensure that future generations enjoy the same clean air and prosperity that regulations have made possible.

By instead considering retracting clean-air rules, the EPA is calling into question the expertise of countless scientists who have provided their objective advice over decades to set standards designed to protect human lives. In many cases, industries won’t want to go back to past polluting ways, but lifting clean air rules means future investment might not be as protective. And it increases future regulatory uncertainty for industries.

The past offers a clear lesson: Investing in clean air is not just good for public health – it’s good for the economy. With a track record of saving lives and delivering trillion-dollar benefits, air quality regulations remain one of the greatest policy success stories in American history.

Felice J. Freyer: Sending ‘Subacute’ patients home

UMass Memorial Medical Center University Hospital at dawn

Cxw1044 - Photo

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

After a patch of ice sent Marc Durocher hurtling to the ground, and doctors at UMass Memorial Medical Center, in Worcester, repaired the broken hip that resulted, the 75-year-old electrician found himself at a crossroads.

He didn’t need to be in the hospital any longer. But he was still in pain, unsteady on his feet, unready for independence.

Patients nationwide often stall at this intersection, stuck in the hospital for days or weeks because nursing homes and physical rehabilitation facilities are full. Yet when Durocher was ready for discharge in late January, a clinician came by with a surprising path forward: Want to go home?

Specifically, he was invited to join a research study at UMass Chan Medical School, testing the concept of “SNF at home” or “subacute at home,” in which services typically provided at a skilled nursing facility are instead offered in the home, with visits from caregivers and remote monitoring technology.

Durocher hesitated, worried he might not get the care he needed, but he and his wife, Jeanne, ultimately decided to try it. What could be better than recovering at his home in Auburn with his dog, Buddy?

Such rehab at home is underway in various parts of the country — including New York, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — as a solution to a shortage of nursing home and rehab beds for patients too sick to go home but not sick enough to need hospitalization.

Staffing shortages at post-acute facilities around the country led to a 24% increase over three years in hospital length of stay among patients who need skilled nursing care, according to a 2022 analysis. With no place to go, these patients occupy expensive hospital beds they don’t need, while others wait in emergency rooms for those spots. In Massachusetts, for example, at least 1,995 patients were awaiting hospital discharge in December, according to a survey of hospitals by the Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association.

Offering intensive services and remote monitoring technology in the home can work as an alternative — especially in rural areas, where nursing homes are closing at a faster rate than in cities and patients’ relatives often must travel far to visit. For patients of the Marshfield Clinic Health System who live in rural parts of Wisconsin, the clinic’s six-year-old SNF-at-home program is often the only option, said Swetha Gudibanda, medical director of the hospital-at-home program.

“This is going to be the future of medicine,” Gudibanda said.

Marc and Jeanne Durocher were thrilled that a clinical trial at UMass Chan Medical School enabled Marc to recover from hip surgery at home, in Auburn, Massachusetts.

But the concept is new, an outgrowth of hospital-at-home services expanded by a covid-19 pandemic-inspired Medicare waiver. SNF-at-home care remains uncommon, lost in a fiscal and regulatory netherworld. No federal standards spell out how to run these programs, which patients should qualify, or what services to offer. No reimbursement mechanism exists, so fee-for-service Medicare and most insurance companies don’t cover such care at home.

The programs have emerged only at a few hospital systems with their own insurance companies (like the Marshfield Clinic) or those that arrange for “bundled payments,” in which providers receive a set fee to manage an episode of care, as can occur with Medicare Advantage plans.

In Durocher’s case, the care was available — at no cost to him or other patients — only through the clinical trial, funded by a grant from the state Medicaid program. State health officials supported two simultaneous studies at UMass and Mass General Brigham hoping to reduce costs, improve quality of care, and, crucially, make it easier to transition patients out of the hospital.

The American Health Care Association, the trade group of for-profit nursing homes, calls “SNF at home” a misnomer because, by law, such services must be provided in an institution and meet detailed requirements. And the association points out that skilled nursing facilities provide services and socialization that can never be replicated at home, such as daily activity programs, religious services, and access to social workers.

But patients at home tend to get up and move around more than those in a facility, speeding their recovery, said Wendy Mitchell, medical director of the UMass Chan clinical trial. Also, therapy is tailored to their home environment, teaching patients to navigate the exact stairs and bathrooms they’ll eventually use on their own.

A quarter of people who go into nursing homes suffer an “adverse event,” such as infection or bed sore, said David Levine, clinical director for research for Mass General Brigham’s Healthcare at Home program and leader of its study. “We cause a lot of harm in facility-based care,” he said.

By contrast, in 2024, not one patient in the Rehabilitation Care at Home program of Nashville-based Contessa Health developed a bed sore and only 0.3% came down with an infection while at home, according to internal company data. Contessa delivers care in the home through partnerships with five health systems, including Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, the Allegheny Health Network in Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin’s Marshfield Clinic.

Contessa’s program, which has been providing in-home post-hospital rehabilitation since 2019, depends on help from unpaid family caregivers. “Almost universally, our patients have somebody living with them,” said Robert Moskowitz, Contessa’s acting president and chief medical officer.

The two Massachusetts-based studies, however, do enroll patients who live alone. In the UMass trial, an overnight home health aide can stay for a day or two if needed. And while alone, patients “have a single-button access to a live person from our command center,” said Apurv Soni, an assistant professor of medicine at UMass Chan and the leader of its study.

But SNF at home is not without hazards, and choosing the right patients to enroll is critical. The UMass research team learned an important lesson when a patient with mild dementia became alarmed by unfamiliar caregivers coming to her home. She was readmitted to the hospital, according to Mitchell.

The Mass General Brigham study relies heavily on technology intended to reduce the need for highly skilled staff. A nurse and physician each conducts an in-home visit, but the patient is otherwise monitored remotely. Medical assistants visit the home to gather data with a portable ultrasound, portable X-ray, and a device that can analyze blood tests on-site. A machine the size of a toaster oven dispenses medication, with a robotic arm that drops the pills into a dispensing unit.

The UMass trial, the one Durocher enrolled in, instead chose a “light touch” with technology, using only a few devices, Soni said.

The day Durocher went home, he said, a nurse met him there and showed him how to use a wireless blood pressure cuff, wireless pulse oximeter, and digital tablet that would transmit his vital signs twice a day. Over the next few days, he said, nurses came by to take blood samples and check on him. Physical and occupational therapists provided several hours of treatment every day, and a home health aide came a few hours a day. To his delight, the program even sent three meals a day.

Durocher learned to use the walker and how to get up the stairs to his bedroom with one crutch and support from his wife. After just one week, he transitioned to less-frequent, in-home physical therapy, covered by his insurance.

“The recovery is amazing because you’re in your own setting,” Durocher said. “To be relegated to a chair and a walker, and at first somebody helping you get up, or into bed, showering you — it’s very humbling. But it’s comfortable. It’s home, right?”

Felice J. Freyer is a veteran medical reporter.

Found and lost winter

“Davis Brothers, Oxen on Pleasant Street” (Portsmouth, N.H.), circa 1867, in Lynn Cazabon’s show “Losing Winter,’’ through March 30 at 3S Artspace, Portsmouth, through March 3o.

The gallery explains that Lynn Cazabon presents a unique and site-specific “archive of memories and emotions about winter, revealing the personal and cultural ties we have to the season and reflecting upon what we are collectively losing due to climate-change impacts on seasonal patterns.’’

Sonali Kolhatkar: As Trump dismantles FEMA, etc., states need to create climate superfunds

Flooding in downtown Montpelier, Vt., on July 11,2023

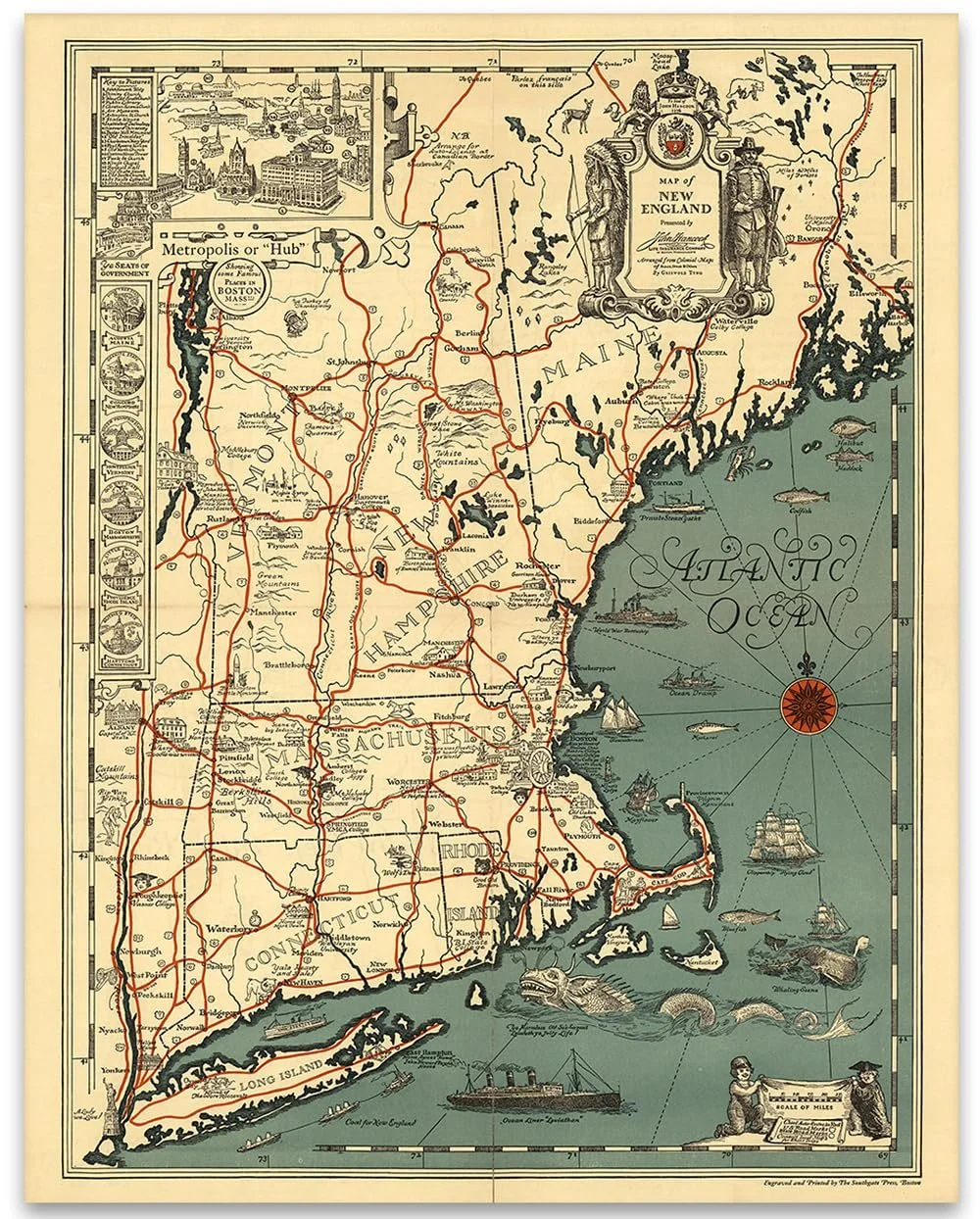

Global warming has been bringing more frequent extreme weather events around America in recent years. Vermont in May 2024 became the first state to establish a climate superfund.

-Photo by Air National Guard Senior Master Sgt. Michael Davis

Via OtherWords.org

Rebuilding from California’s recent wildfires will cost more than a quarter of a trillion dollars — an unprecedented amount. The estimated damage from Hurricane Helene in the Southeast is almost as much, on the order of $250 billion.

Who will pay for that damage? It’s a question plaguing localities around the country as climate change makes these disasters increasingly common.

Some states are landing on a straightforward answer: fossil-fuel companies.

The idea is inspired by the “superfunds” used to clean up industrial accidents and toxic waste. The Superfund program goes back to 1980, when Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). The law fined polluters to finance the clean up of toxic spills.

Thanks to the hard work of groups such as the Vermont Public Interest Research Group and Vermont Natural Resources Council, Vermont recently became the first state to establish a climate superfund in May 2024.

Months later, New York followed suit, again in response to pressure from environmental groups. Both bills require oil and gas companies to pay billions into a fund designated for climate-related cleanup and rebuilding.

Now California is considering a similar law in the wake of its disastrous wildfires. Maryland, Massachusetts and New Jersey may take up the idea as well.

It’s an idea whose time has come, especially now that states are less able to rely on the federal government. The Trump administration is disabling government agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) with major cuts and putting conditions on other aid.

At the recent Conservative Political Action Committee (CPAC) conference, Trump aide Ric Grenell unabashedly endorsed “squeezing” California’s federal funds unless they “get rid of the California Coastal Commission.” (Trump apparently hates the commission, the Fresno Bee explains, because it prevents “wealthy people from turning public beaches into private enclaves.”)

Fossil-fuel companies — the lead perpetrators of climate disasters — spent more than $450 million to elect their favored candidates, including Trump. In return, Trump has promised to speed up oil and gas permits and stacked his cabinet with oil-friendly executives.

Why should taxpayers have to foot the bill to clean up the destruction wrought by this industry, one of the most profitable the world has ever known? As a spokesperson for New York Gov. Kathy Hochul said, “corporate polluters should pay for the wreckage caused by the climate crisis — not everyday New Yorkers.”

Not surprisingly, 22 Republican-led states disagree. They’ve sued to block New York’s law and protect oil and gas profits at the expense of ordinary people. They have no answer for the question of who pays for recovery from climate disasters or helps people reeling from one disaster after another.

Fossil-fuel companies can think of paying into a climate superfund as the cost of doing business. If they’re in the business of extracting and selling a fuel that destroys the planet, it’s only fair they pay to clean up the damage.

And the public agrees. Data For Progress found more than 80 percent of voters support holding fossil-fuel companies responsible for the impact of carbon emissions.

To be fair, a climate superfund is a “downstream” solution to the climate crisis, one that seeks to raise the costs to perpetrators. A climate superfund can pay to rebuild homes, but it cannot replace priceless family heirlooms or undo the trauma of surviving a disaster. Most of all, it cannot bring back lives lost. It is only one tool in a multi-pronged tool box to end the climate crisis.

Upstream solutions centering the prevention of climate change — that is, reducing carbon emissions at their source — must be at the center of our fight if humanity is to survive. But in the meantime, fossil fuel polluters should pay.

Sonali Kolhatkar is the host of Rising Up With Sonali, a television and radio show on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations.

And we’re still divided

“The past is never dead. It's not even past" — William Faulkner (1897-1962) of Mississippi in his 1950 novel Requiem for a Nun

Col. John Blackburne Woodward, Maj. Joseph B. Leggett and Lt. Col. William A. McKee of the 13th National Guard Regiment, New York, ca. 1863, (oil-painted Imperial albumen print), by unknown photographer. This is in the March 21-May 10 show “A House Divided: Photography and the Civil War” at the Art Museum, University of St. Joseph, West Hartford, Conn.

The show documents aspects of the Civil War as seen through the lens of the most gifted artist-photographers of 19th Century America. All works are from the collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg.

‘Pseudo-scientific Fantasy’

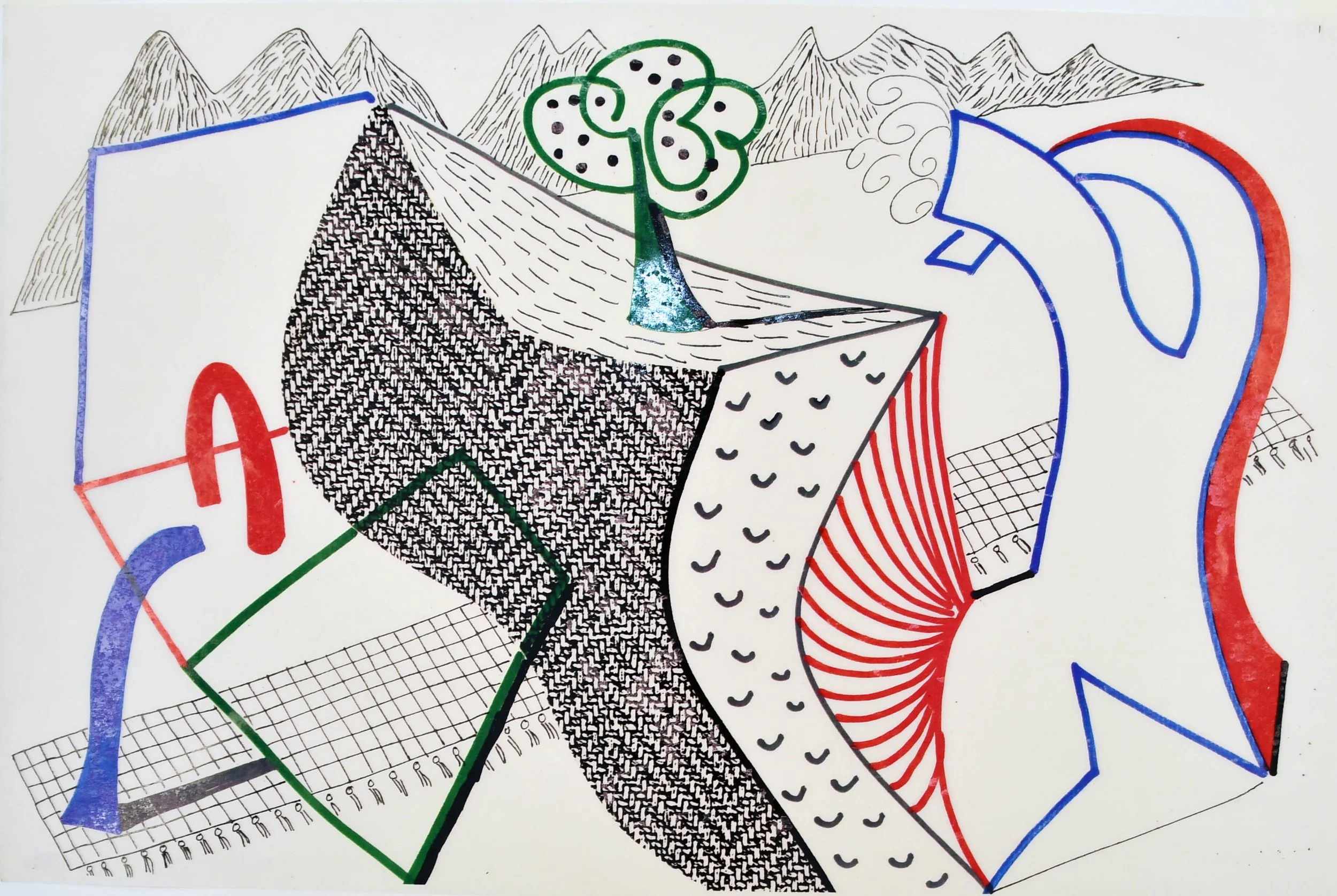

David Hockney illustration for James Sellars’s film Haplomatics, in the show “David Hockney & James Sellars: Haplomatics,’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art through Oct. 5

The museum says that the show “explores the wild realm of pseudo-scientific fantasy in the visual textual and musical collaboration between the artist David Hockney and the composer James Sellars.

“Their work together in the late 1980s became a synergy of art, technology, and music that resulted in a multi-media masterpiece, the animated film Haplomatics. The film introduces a genus of abstract beings called Haplomes, which come to life through Hockney’s prints and Sellars’s narration and innovative musical score.

“Haplomatics,’’ the exhibition, features Hockney’s innovations in printmaking with the thirty-five xerographic prints that were used to create the film’s visual effects.’’

In Boston, anyway, the 13th floor is losing its infamy

Aerial view of Downtown Boston in June 2017

AbhiSuryawanshi photo

Would you think twice about renting on the 13th floor?

For high rises in the United States, skipping the number 13 was once a standard convention. Many taller structures referred to their 13th floor as 14 and renumbered the rest of the building accordingly, a bizarre ruse apparently meant to save building managers from their more superstitious clients.

However, the unlucky number appears to be losing its infamy.

Most of Boston’s 20 tallest buildings do not bother skipping the 13th floor, according to a Boston Guardian review. Almost all of the city’s office skyscrapers bravely lease out space on floor number 13, and some newer residential high rises and hotels have also thrown away the practice.

Hotels may be the city’s last bastion of construction superstition. Spots such as the Park Plaza Hotel, the Custom House Tower and the new Newbury Hotel still go directly from floors 12 to 14, a comfort to triskaidekaphobic guests. It is unclear whether these hotels also ban black cats, broken mirrors or towering ladders.

Prospective hotel guests rarely fret about 13, noted Suzanne Wenz, director of marketing for the Newbury. The practice probably endures in older hotels because of tradition, she said.

“It’s just traditionally been that way,” Wenz said. “I personally have not heard of anyone complaining about being on the 13th floor.”

On the residential side, most recent developments are fearless, offering 13th floor apartments and condos with apparent impunity. Still, a few new buildings remain holdouts. The Viridian in the Fenway skips the number, and the Millennium Tower downtown cautiously avoids both 13 and 44, an unlucky number in East and Southeast Asian cultures. The developers did not respond to requests for comment.

Local real estate brokers say 13 is rarely a dealbreaker for condo owners. Most clients do not worry about the number, and 13th floor condos are unfortunately not available at a discounted rate for daring buyers willing to try their luck. That being said, some condo owners are in favor of skipping floor 13 in order to accommodate the small percentage of people who hold this superstition thinking they may as well not miss the sale.

“If you don’t have to put it in, and you can take it out because it’s your choice, why even deal with it?” said residential broker Kevin Ahearn. “It’s just a judicious thing to do.”

The practice appears to be waning. The Moxy, a downtown hotel aimed at millennials, does not skip 13, even though its older corporate siblings like the Park Plaza still follow the longstanding tradition.

For hotels and residential buildings, this change may be driven partly by consumers. Superstition is not unheard of nowadays, but few people will go out of their way to avoid an unlucky number.

“I don’t know that people give it a lot of thought these days,” said Wenz.

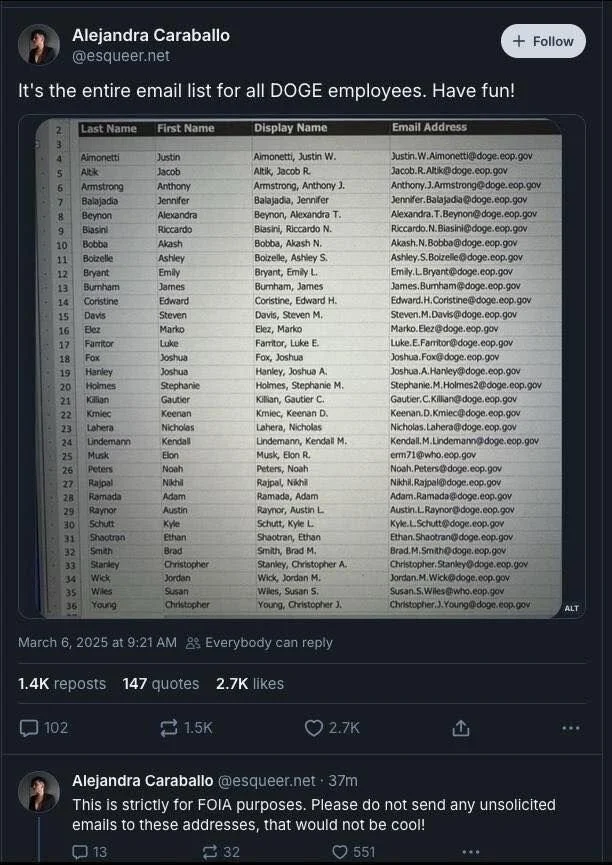

Note the egg prices in particular!

At Boston’s Parker House hotel in 1949. Now called the Omni Parker House, it remains a favorite meeting place for people in Massachusetts politics.The hotel was founded in 1855, with the current hotel structure dating to 1927.

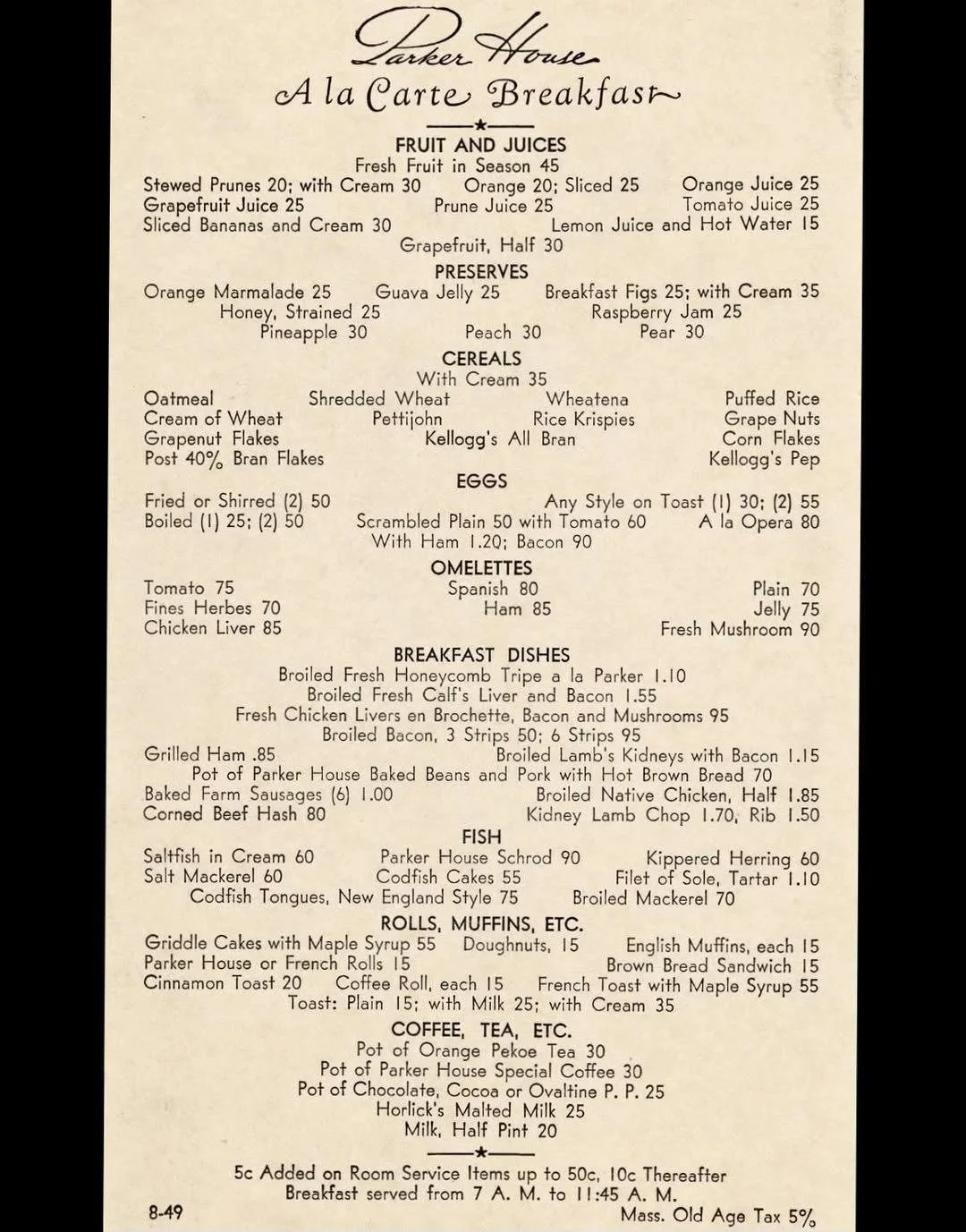

Llewellyn King: We need a Magna Carta to challenge Trump tyranny

King John being forced to sign the Magna Carta.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Sitting behind President Trump at his inauguration were men who might well be called the barons of America: the big-tech billionaires who control vast wealth and public awe. They are so high in Trump’s esteem that he seated them in front of his Cabinet.

When King John of England was crowned, in 1199, barons also attended him. They were the barons of England, although most were of French descent — the result of the conquest of England in 1066 by William, Duke of Normandy, who defeated King Harold II of England in the Battle of Hastings.

The difference between John’s coronation and those of his father, Henry II, and brother, Richard I, was that he didn’t make the customary promises to uphold the rights and the norms of conduct that had become a kind of unofficial constitution. John neither embraced those norms then nor abided by them later.

King John was known to be vengeful and petty, tyrannical and greedy, but is believed to have been a relatively good administrator and a passable soldier -- although many of his financial problems resulted from the loss in war of English lands in Normandy.

Those wars and expenditures by his father and brother on fighting the Third Crusade meant that John had a money problem. He solved the problem with high taxes and scutage — payments that were made in lieu of military service, often by rich individuals.

John also had a “deep state” problem.

The king’s administration had become extremely efficient, bureaucratic, and especially good at taxation and coercion, which angered the nobles. They were getting pushed around.

When the barons had had enough, they told the king to behave, or they would install one of the pretenders to the throne. They met in long negotiations at Runnymede, a meadow along the Thames, 22.5 miles upriver from what is now Central London. It is pretty well unchanged today, save for a monument erected by the American Bar Association, in 1957.

The barons forced on John a document demanding his good behavior, and impressing upon him that even the king was not above the law.

The document that was signed on June 15, 1215 was the Magna Carta (Great Charter), limiting the king’s authority and laying down basic rules for lawful governance.

In all there are 63 sections in the document, which have affected Western culture and politics for almost 800 years. The Magna Carta is part of English and American common law, and was a foundational document for the U.S. Constitution.

It stated that the king was subject to the laws of the time, that the church could be free of the king’s administration and his interference, and that the rights of the barons and commoners were respected. Particularly, it said that no one should be imprisoned without due process.

Today’s barons in America are undoubtedly the big-tech entrepreneurs who have not only captured great wealth but also have an air of infallibility.

While John has been hard-handled by history, the Magna Carta has done superbly. John was saddled with the epithet “Bad King John” and no other English monarch has been named John.

When an American president is showing some of the excesses of John, isn’t it time for the great commercial and technological chiefs, who have so far sworn fealty to Trump, to sit him down beside another great river, the Potomac, and tell him a few truths, just as happened at Runnymede?

Since Trump’s inauguration, U.S. national and international status has deteriorated. Chaos has reigned — the government has nearly ceased to function, a pervasive fear for the future has settled in a lot of Americans, there is embarrassment and anger over the trashing of laws, circumvention of the Constitution, tearing up of treaties, aggression towards our neighbors, and a general governance by whim and ego.

America’s barons need to tell the president: You aren’t a king. Leave the free press free. Abide by the decisions of the courts. Stay within the law. Respect free speech wherever it is practiced. Above all, respect the Constitution, the greatest document of government probity written since the Magna Carta.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, as well as a businessman, most notably now as an international energy-sector consultant.

White House Chronicle

Centerville Mill on the Pawtuxet River, built during West Warwick’s 19th Century heyday as a textile-making center.

‘Growth and decay’

“Kaboom!,” linocut monotype, by Julia Talcott, in her show “Subject to Change,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, April 2-27.

She says:

“This exhibition presents printmaking from 2012 to the present. My work reflects my interest in the natural world and its intersection with the man-made world. I like to observe patterns, pull them apart, and then re-imagine them as printed pieces.

“Creating them as linoleum and woodblock prints, I produce a vocabulary of images and then work intuitively to collage them back together into new forms.

“I alternate between abstraction and representational images, with color and black and white pallets to weave images together. I strive to express the vitality of growth and decay in a physical and spiritual world.’’

Chris Powell: Must everyone be on the Conn. Payroll?

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Are annual incomes of $250,000 a year for a couple and $100,000 for a single person not enough to support a family in Connecticut?

That’s the implication of legislation proposed by many state legislators that would pay people $600 every year for each of as many as three of their children. Along with the so-called earned income tax credits offered to the working poor by the federal government and state government, this kind of thing is starting to look like a program of guaranteed annual income.

The original idea of earned income tax credits was to increase the incentive to work of poor people who were receiving welfare benefits. But welfare benefits for people earning more than $100,000 a year imply that poverty and inflation in Connecticut have exploded even as state and federal elected officials have been proclaiming prosperity.

This implication is strengthened by clamor in the General Assembly to require the state’s Medicaid program to provide free diapers to insured infants -- and it is estimated that 40 percent of births in Connecticut are now to women covered by Medicaid. That is, women on welfare.

The cost of living has soared in recent years. But it has not yet occurred to elected officials that the poor might be helped most simply by stopping inflation, not by creating more welfare, which adds to inflation if it is not matched by an increase in economic production.

Poor people also might be helped still more by improving their education and work skills. But Connecticut has given up on education, having replaced it with social promotion, thereby guaranteeing that every year thousands of young people reach adulthood qualified only for menial work -- and needing more welfare.

DeLAURO'S KICKBACKS: The federal government is the biggest business in the world and very lucrative for those in power.

Take Connecticut U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro, now serving her 34th year in Congress. When Democrats have held the majority in the House of Representatives, DeLauro has been chairman of the House Appropriations Committee. Now that Republicans hold the majority -- just barely -- DeLauro is the committee's ‘‘ranking" member, the leading member of the minority party, who still may retain great influence over appropriations.

Simultaneously DeLauro has been national finance chairwoman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and has just been elected to another term.

So if you want money from the government, DeLauro is a good person to befriend, and one way of befriending her is to donate money to the Democratic fundraising committee she runs.

This is a kickback operation. DeLauro didn’t invent it but gets much credit for distributing federal money throughout Connecticut and the country for all sorts of goodies financed by borrowing and money creation -- that is, inflation money.

Apparently someone else in the government is in charge of inflation, though DeLauro acts as if she has no idea who it is.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Voices on the Maine Coast

Gulf of Maine as seen from a whale watching boat

Dirk Ingo Franke photo

Arthur Allen: Distinguished, if arrogant, surgeon who was often wrong about COVID, To lead the FDA

Dr. Marty Makary in 2012

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

“He went from being a pretty reasonable person to saying a lot of things that were over the top and unnecessary.’’

— Ashish Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health

Panelists at a COVID conference last fall were asked to voice their regrets — policies they had supported during the pandemic but had come to see as misguided. COVID contact tracing, one said. Closing schools, another said. Vaccine mandates, a third said.

When Marty Makary’s turn came, the Johns Hopkins University surgeon said, “I can’t think of anything,” adding, “The entire COVID policy of three to four years felt like a horror movie I was forced to watch.”

It was a characteristic response for Makary, President Trump’s nominee to lead the Food and Drug Administration, who looks set to be confirmed after a Senate committee hearing on Thursday. A decorated doctor and a brash critic of many of his medical colleagues, Makary drew Trump’s attention during the pandemic with frequent appearances on Fox News shows such as Tucker Carlson Tonight, in which he excoriated public health officials over their handling of covid.

Many former FDA officials and scientists with knowledge of the agency are optimistic about Makary — to a degree.

“He’s a world-class surgeon, and he has health policy expertise,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, a Brown University professor of epidemiology and former colleague of Makary’s at Johns Hopkins. “If you have pancreatic cancer, he’s the person you want to operate on you. The university is probably losing a lot of money to not have him doing that work.”

His critics say he at times exaggerated the harms of COVID vaccines and undersold the dangers of the virus, contributing to a pandemic narrative that led many Americans to shun the shots and other practices intended to curb transmission and reduce hospitalizations and deaths.

Should he take the reins at the FDA, transitioning from gadfly to the head of an agency that regulates a fifth of the U.S. economy, Makary would have to engage in the thorny challenges of governing.

“Makary spent the pandemic raving against the medical establishment as if he were an outsider, which he wasn’t,” said Jonathan Howard, a New York City neurologist and the author of We Want Them Infected, a book that criticizes Makary and other academics who opposed government policies. “Now he really is the establishment. Everything that happens is going to be his responsibility.”

At his confirmation hearing, Makary sounded a lower-key tone, extolling the FDA’s professional staff and promising to apply good science and common sense in the service of attacking chronic disease in the U.S., including by studying food additives and chemicals that could be contributing to poor health.

“We need more humility in the medical establishment. You have to be willing to evolve your position as new data comes in,” he testified. What makes a great doctor “is not how much you know; it’s your humility and your willingness to learn, as you go, from patients.”

Colleagues have applauded Makary’s skill and intelligence as a surgeon and medical policy thinker. He contributed to a 2009 surgery checklist believed to have prevented thousands of mistakes and infections in operating rooms. He wrote a widely cited 2016 paper claiming that medical errors were the third-leading cause of death in the United States, although some researchers said the assertion was overblown. He’s also founded or been a director for companies and said in the hearing that a surgical technique he invented eventually could help cure diabetes.

Humility, however, has not been Makary’s most obvious trait.

During the pandemic, he took to op-eds and conservative media with controversial positions on public health policy. Some proved astute, while others look less prescient in hindsight.

In December 2020, Makary defied established scientific knowledge and said that vaccination of 20% of the population would be enough to create “herd immunity.”

In a February 2021 Wall Street Journal piece, he predicted that COVID would virtually disappear by April because so many people would have become immune through infection or vaccination. The U.S. death toll from COVID stood at 560,000 that April, with an additional 650,000 deaths to come. In June 2021, he said he had been unable to find evidence of a single COVID death of a previously healthy child. By then there were many reports of such deaths, although children were much less likely than older people to suffer severe disease.

In February 2023, Makary testified in Congress that the Chinese lab-leak theory of COVID’s origin was a “no brainer,” a surprisingly unequivocal statement for a scientist discussing a scientifically unresolved issue.

Some public health officials felt Makary gratuitously attacked authorities working in difficult circumstances.

“He went from being a pretty reasonable person to saying a lot of things that were over the top and unnecessary,” said Ashish Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, who was the White House COVID-19 response coordinator under President Joe Biden.

And while almost everyone involved in fighting COVID has admitted to getting things wrong during the pandemic, Jha said, “I never had any sense from Marty that he did.”

Makary did not respond to requests for comment.

Makary accused Biden administration officials of ignoring emerging evidence that previous infection with covid could be as or more effective against future infection than vaccination. While he was probably right, Nuzzo said, his statements seemed to encourage people to get infected.

“It’s reasonable to say that vaccine mandates weren’t the right approach,” she said. “But you can also understand that people were trying to blindly stumble our way out of the situation, and some people thought vaccine mandates would be expedient.”

At Johns Hopkins, for example, Nuzzo opposed a booster mandate for the campus in 2022 but understood the final decision to require it. School authorities were intent on bringing students back to campus and worried that outbreaks would force them to shut down again, she said.

“You can argue that seat belt laws are bad because they impinge on civil rights,” Howard said. “But a better thing to do would be to urge people to wear seat belts.”

Makary’s statements had “no grace,” he said. “These were people dealing with an overwhelming virus, and he constantly accused them of lying.”

Several public health officials were particularly upset by the way Makary cast aspersions on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s vaccine-safety program. In a Jan. 16, 2023, appearance on Tucker Carlson’s Fox News show, Makary said the CDC had “tried to quickly downplay” evidence of an increased risk of stroke in Medicare beneficiaries who got a COVID booster. In fact, the CDC had detected a potential signal for additional strokes in one database, and in the interest of transparency it released that information, Nuzzo said. Further investigation found that there was no actual risk.

During his confirmation hearing, Makary’s pandemic views were mostly left unexplored, but Democratic and Republican senators repeatedly probed for his views on the abortion drug mifepristone, which became easier to use without direct medical supervision because of a 2021 FDA ruling. Many Republicans want to reverse the FDA ruling; Democrats say there are reams of evidence that support the drug’s safety when taken by a woman at home.

Makary tried to satisfy both parties. He told Sen. Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.) he would be led by science and had no preconceived ideas about mifepristone’s safety.

Questioned by Republican Bill Cassidy, chair of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee and an abortion foe, he said he would examine ongoing data on the drug from the FDA’s risk evaluation system, which gathers reports from the field.

The abortion pill question exemplifies the kind of dilemmas Makary will face at the FDA, Jha said.

“He’s going to have to decide whether he listens to the scientists in his administration, or his boss, who often disagrees with science,” he said. “He’s a smart, thoughtful guy and my hope is he’ll find his way through.”

“The two most important organs for the FDA commissioner are the brain and the spine,” said former FDA deputy commissioner Joshua Sharfstein. “The spine because there’s attempted influence coming from many directions, not just political but also commercial and from multiple advocacy communities. It’s very important to stand up for the agency’s success.”

Arthur Allen is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter.

We’d like to speak with current and former personnel from the Department of Health and Human Services or its component agencies who believe the public should understand the impact of what’s happening within the federal health bureaucracy. Please message KFF Health News on Signal at (415) 519-8778 or get in touch here.

Arthur Allen: aallen@kff.org, @ArthurAllen202

Related Topics

Creepy worms are moving into New England

SREEJITH VISWANATHAN photo

Hammerhead worm

Excerpted from an ecoRI News article by Frank Carini.

This diverse group of invertebrates are long, soft, typically lack appendages, and usually have no eyes. They also have some of the best names: hammerhead, snake, leech and sand striker.

The last — a fearsome-jawed worm that eats fish and can grow up to 10 feet long — is typically found in shallow tropical marine waters around the world, but the other three can be found here. The first two, however, are invasive — one can jump and the other is toxic.

Native to Asia and Madagascar, the hammerhead worm was transported to Europe and the United States in shipments of exotic plants. It has been in the United States since the early 1900s and is most commonly found in states such as Louisiana, where conditions are warm and humid. But now, as the climate warms, these invasive worms are spreading.

In 2022, some of these worms were found in a Harrisville, R.I., yard….

Hammerhead worms produce a neurotoxin, tetrodotoxin, which is also found in puffer fish. These worms can also transmit harmful parasites to humans and animals, and they regenerate from segments if they are cut up.

The run of the Mill

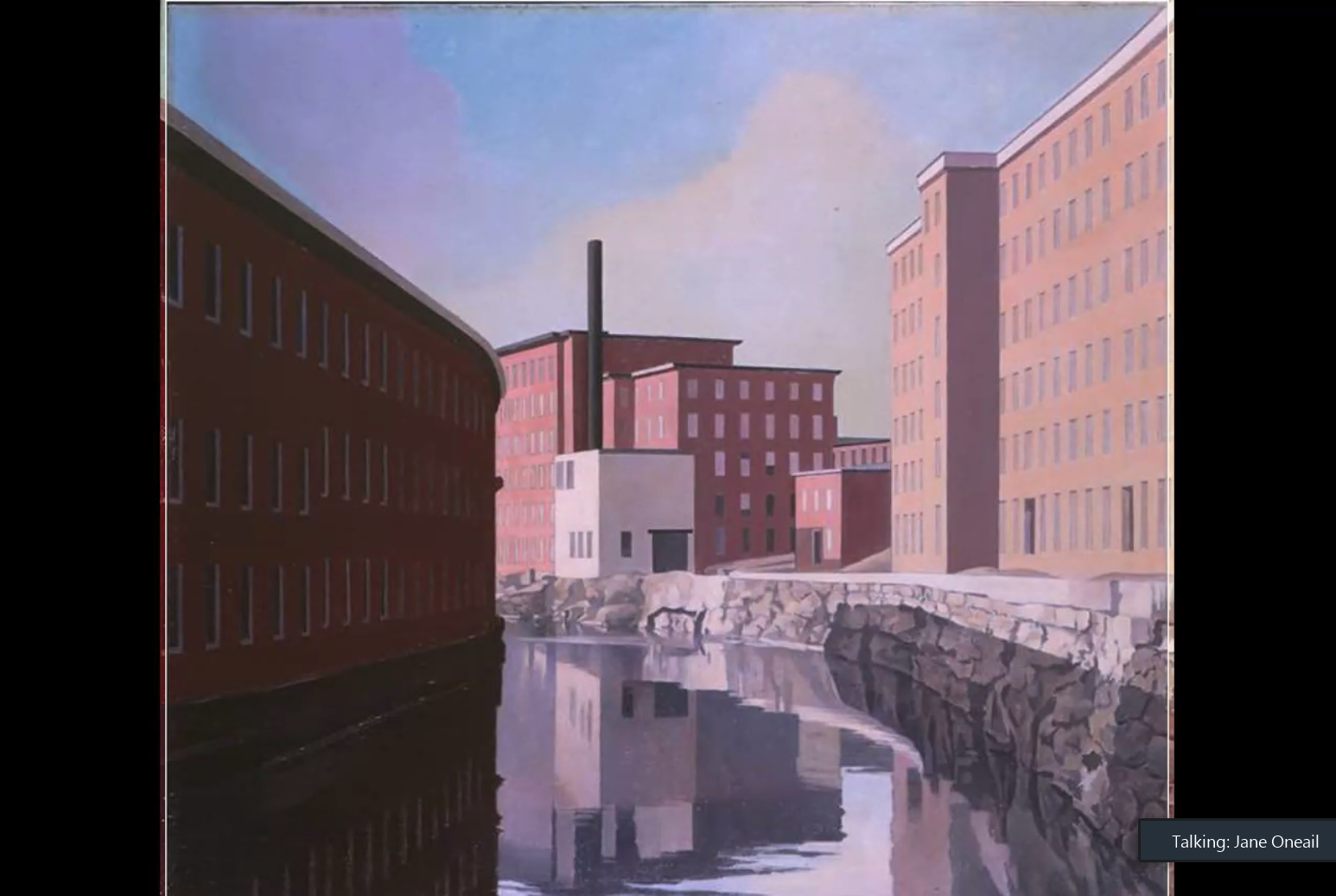

“Amoskeag Canal” (1948), (oil on canvas), by Charles Sheeler, at the Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, N.H.

The Amoskeag Manufacturing Co., in Manchester, along the Merrimack River, was once the largest cotton-textile factory in the world.

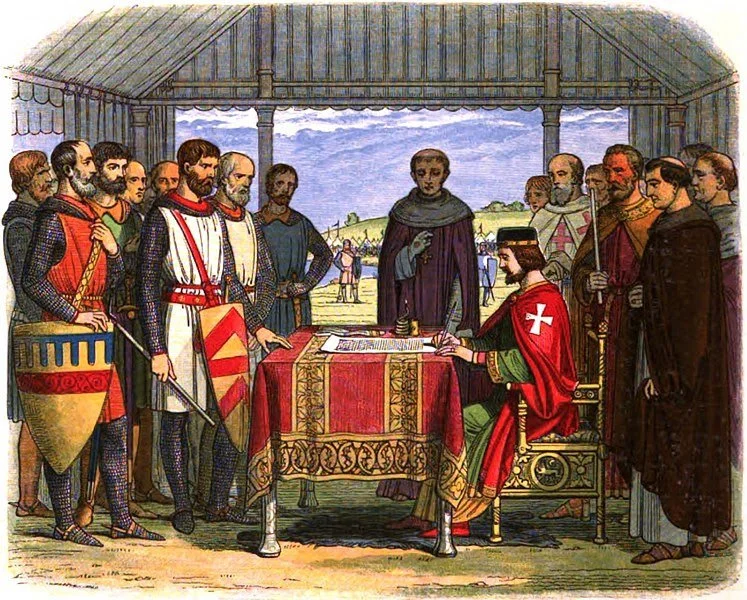

Allison Stanger: Another Musk/DOGE/Trump threat to privacy and Democracy and a Corruption spawner

From The Conversation (except for image above)

MIDDLEBURY, VT.

Allison Stanger is political-science professor at Middlebury College and an expert on the role of technology in society.

She receives funding from the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society, Harvard University.

The Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, has secured unprecedented access to at least seven sensitive federal databases, including those of the Internal Revenue Service and Social Security Administration. This access has sparked fears about cybersecurity vulnerabilities and privacy violations.

Another concern has received far less attention: the potential use of the data to train a private company’s artificial intelligence systems.

The White House press secretary said government data that DOGE has collected isn’t being used to train Musk’s AI models, despite Elon Musk’s control over DOGE. However, evidence has emerged that DOGE personnel simultaneously hold positions with at least one of Musk’s companies.

At the Federal Aviation Administration, SpaceX employees have government email addresses. This dual employment creates a conduit for federal data to potentially be siphoned to Musk-owned enterprises, including xAI. The company’s latest Grok AI chatbot model conspicuously refuses to give a clear denial about using such data.

As a political scientist and technologist who is intimately acquainted with public sources of government data, I believe this potential transmission of government data to private companies presents far greater privacy and power implications than most reporting identifies. A private entity with the capacity to develop artificial intelligence technologies could use government data to leapfrog its competitors and wield massive influence over society.

For AI developers, government databases represent something akin to finding the Holy Grail. While companies such as OpenAI, Google and xAI currently rely on information scraped from the public internet, nonpublic government repositories offer something much more valuable: verified records of actual human behavior across entire populations.

This isn’t merely more data – it’s fundamentally different data. Social media posts and web browsing histories show curated or intended behaviors, but government databases capture real decisions and their consequences. For example, Medicare records reveal health care choices and outcomes. IRS and Treasury data reveal financial decisions and long-term impacts. And federal employment and education statistics reveal education paths and career trajectories.

What makes this data particularly valuable for AI training is its longitudinal nature and reliability. Unlike the disordered information available online, government records follow standardized protocols, undergo regular audits and must meet legal requirements for accuracy.

Every Social Security payment, Medicare claim and federal grant creates a verified data point about real-world behavior. This data exists nowhere else with such breadth and authenticity in the U.S.

Most critically, government databases track entire populations over time, not just digitally active users. They include people who never use social media, don’t shop online, or actively avoid digital services. For an AI company, this would mean training systems on the actual diversity of human experience rather than just the digital reflections people cast online.

A security guard prevented U.S. Sen. Edward Markey, D-Mass., from entering an EPA building on Feb. 6, 2025, to see DOGE staff working there. Al Drago/Getty Images

The technical advantage

Current AI systems face fundamental limitations that no amount of data scraped from the internet can overcome. When ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini make mistakes, it’s often because they’ve been trained on information that might be popular but isn’t necessarily true. They can tell you what people say about a policy’s effects, but they can’t track those effects across populations and years.

Government data could change this equation. Imagine training an AI system not just on opinions about health care but on actual treatment outcomes across millions of patients. Consider the difference between learning from social media discussions about economic policies and analyzing their real impacts across different communities and demographics over decades.

A large, state-of-the-art, or frontier, model trained on comprehensive government data could understand the actual relationships between policies and outcomes. It could track unintended consequences across different population segments, model complex societal systems with real-world validation and predict the impacts of proposed changes based on historical evidence. For companies seeking to build next-generation AI systems, access to this data would create an almost insurmountable advantage.

Control of critical systems

A company like xAI could do far more with models trained on government data than building better chatbots or content generators. Such systems could fundamentally transform – and potentially control – how people understand and manage complex societal systems. While some of these capabilities could be beneficial under the control of accountable public agencies, I believe they pose a threat in the hands of a single private company.

Medicare and Medicaid databases contain records of treatments, outcomes and costs across diverse populations over decades. A frontier model trained on new government data could identify treatment patterns that succeed where others fail, and so dominate the health-care industry. Such a model could understand how different interventions affect various populations over time, accounting for factors such as geographic location, socioeconomic status and concurrent conditions.

A company wielding the model could influence health care policy by demonstrating superior predictive capabilities and market population-level insights to pharmaceutical companies and insurers.

Treasury data represents perhaps the most valuable prize. Government financial databases contain granular details about how money flows through the economy. This includes real-time transaction data across federal payment systems, complete records of tax payments and refunds, detailed patterns of benefit distributions, and government contractor payments with performance metrics.

An AI company with access to this data could develop extraordinary capabilities for economic forecasting and market prediction. It could model the cascading effects of regulatory changes, predict economic vulnerabilities before they become crises, and optimize investment strategies with precision impossible through traditional methods.

Elon Musk’s xAI company is well financed.

Infrastructure and urban systems

Government databases contain information about critical infrastructure usage patterns, maintenance histories, emergency response times and development impacts.

Every federal grant, infrastructure inspection and emergency response creates a data point that could help train AI to better understand how cities and regions function.

The power lies in the potential interconnectedness of this data. An AI system trained on government infrastructure records would understand how transportation patterns affect energy use, how housing policies affect emergency response times, and how infrastructure investments influence economic development across regions.

A private company with exclusive access would gain unique insight into the physical and economic arteries of American society. This could allow the company to develop “smart city” systems that city governments would become dependent on, effectively privatizing aspects of urban governance. When combined with real-time data from private sources, the predictive capabilities would far exceed what any current system can achieve.

Absolute data corrupts absolutely

A company such as xAI, with Musk’s resources and preferential access through DOGE, could surmount technical and political obstacles far more easily than competitors. Recent advances in machine learning have also reduced the burdens of preparing data for the algorithms to process, making government data a veritable gold mine – one that rightfully belongs to the American people.

The threat of a private company accessing government data transcends individual privacy concerns. Even with personal identifiers removed, an AI system that analyzes patterns across millions of government records could enable surprising capabilities for making predictions and influencing behavior at the population level. The threat is AI systems that leverage government data to influence society, including electoral outcomes.

Since information is power, concentrating unprecedented data in the hands of a private entity with an explicit political agenda represents a profound challenge to the republic. I believe that the question is whether the American people can stand up to the potentially democracy-shattering corruption such a concentration would enable. If not, Americans should prepare to become digital subjects rather than human citizens.