New England in a previous trade war….

From generative AI

“The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 significantly harmed the New England economy by drastically reducing exports, particularly in the textile industry, as other countries retaliated with their own tariffs, leading to a decline in international trade and further exacerbating the Great Depression in the region; this resulted in job losses, factory closures, and depressed wages in key New England manufacturing sectors.

Key points about the Smoot-Hawley impact on New England:

Textile industry hit hard:

New England was a major center for textile production, and with increased tariffs on imported goods, foreign markets retaliated by reducing their purchases of New England textiles, causing significant economic hardship in the region.

Reduced export markets:

The tariff act led to a sharp decline in U.S. exports overall, as other countries imposed retaliatory tariffs, which directly affected New England businesses heavily reliant on international trade.

Job losses and factory closures:

Due to reduced demand for exported goods, many textile factories in New England were forced to scale back production or shut down, resulting in widespread job losses.

Wage depression:

With high unemployment in the region, wages for textile workers in New England also fell, further impacting the local economy.”

Character-building

Photo by Eugene Crist

“There has been more talk about the weather around here this year than common, but there has been more weather to talk about. For about a month now we have had solid cold—firm, business-like cold that stalked in and took charge of the countryside as a brisk housewife might take charge of someone else’s kitchen in an emergency. Clean, hard, purposeful cold, unyielding and unremitting. Some days have been clear and cold, others have been stormy and cold. We have had cold with snow and cold without snow, windy cold and quiet cold, rough cold and indulgent peace-loving cold. But always cold.’’

From “Cold Weather,” by E.B. White (1899-1985), of Brooklin, Maine, from his series “One Man’s Meat,’’ in Harper’s Magazine in 1944.

Support Art

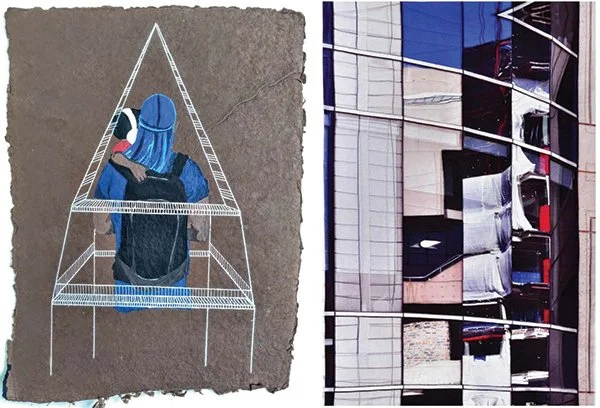

From left, Élan Cadiz, “SCAFFOLD Equity of Treatment” (pen, pencil, acrylic, and flash paint on Shizen paper). Right, Rosalind Daniels, “Construction Reflected” (quilted fiber), in the show “Scaffolding, a AVA Gallery and Art Center, Lebanon,N.H., through March 1.

The gallery explains: “This unique group exhibition features a variety of artwork installed throughout all three levels of AVA’s beautiful historic textile mill building. The exhibition is themed around the term ‘scaffold’ or ‘scaffolding,’ suggesting lifting or providing support.’’

Cold clay

“Winter Landscape,” by Steve Branfman, is his show “Fifty Years Above the Wheel,’’ Feb. 16-May 4, in Duxbury, Mass. at the Art Complex Museum.

Naomi Cahn/Leah A. Plunkett: States trying to limit teens’ exposure to social media

CAMBRIDGE, Mass.

Children should be seen and not heard, or so the old saying goes. A new version of this adage is now playing out across the United States, as more states are passing laws about how children and teens should use social media.

In 2024, approximately half of all U.S. states passed at least 50 bills that make it harder for children and teens to spend time online without any supervision.

Some of the new laws in places such as Maryland, Florida, Georgia and Minnesota include provisions that require parental consent before a child or teenager under the age of 18 can use a social media app, for example. Other new laws prevent targeted marketing to teens based on the personal information they share online. Others recognize child influencers who have active social media followings as workers.

In 1998, long before the age of Instagram or TikTok, the federal government set a minimal baseline for internet safety for children under the age of 13 with the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act. This law, known as COPPA, prevents websites from sharing children’s personal information, among other measures.

As law professors who study children’s online lives and the law, we are tracking state governments that are providing new protections to children when they use social media.

So far, almost all of these new protections are happening at the state level – it remains to be seen how the Trump administration will, if at all, weigh in on how children and teens are spending time on social media.

Almost half of teens ages 13 to 17 said in 2024 they are “almost constantly” online and virtually all of them use the internet every day.

And approximately 40% of children ages 8 to 12 use social media on a daily basis.

Research shows that adolescents who spend more than three hours a day on social media have an increased risk of anxiety and depression.

Almost half of teens have faced online bullying or harassment, with older teen girls most likely to have experienced this. Social media use has been linked to self-harm in some cases.

In 2023, 41 states and the District of Columbia sued Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, claiming that it was harming children. Although Meta tried to have the case dismissed, it is still moving forward.

States including New York and California have made a number of legal changes since 2023 that make it safer for adolescents to spend time online.

California, for example, has expanded information protection for young social media users by limiting apps from collecting kids’ and teens’ geolocation data.

Utah and Florida have raised the age for social media use. Children under the age of 14 cannot open their own social media account, and the platforms are supposed to shut down any such accounts used by children in those states.

In 2024, the Utah Legislature determined that social media was similar to regulated “products and activities” like cars and medication that create risks for minors.

Utah’s new law requires social media platforms to verify a user’s age, such as by requiring a photo ID.

A 2024 Tennessee law allows minors to open their own accounts but requires that social media companies ensure that anyone under the age of 18 has parental consent to do so.

Some states, including Texas and Florida, are trying to create a different experience for minors once they have an account on a social media platform. They are blocking apps from sending targeted advertisements to minors or, in states such as New York, curating social media feeds based on an algorithm instead of based on the minors’ own choices.

A growing number of states have also focused on creating more protections for children influencers and vloggers, who regularly post short videos and images on social media and often have other young people following their content. So far, California, Illinois and Minnesota have passed child digital entertainer laws since 2023.

All of these laws set up financial protections for child influencers. Illinois’ law requires child influencers to receive a portion of the profits they make from their content. Minnesota’s law includes privacy protections: forbidding children under the age of 14 from working as influencers and giving them the right to later delete content, even when their parents have created the post or video.

These laws face different legal challenges. For example, some private industry groups claim these laws restrict free speech or the rights of parents. The U.S. Supreme Court is now considering – for the first time since 1997 – the constitutionality of age restrictions for social media usage.

States across the political spectrum, as well as social media companies themselves, are creating more protections for kids whose online activity might suggest that federal law reform will finally happen.

Members of a dance group in Times Square on Jan. 14, 2025, record videos to be used for social media. Adam Gray/Getty Images

Federal action on social media

Congress has considered new online privacy legislation for children in the past 25 years, including banning targeted ads. But nothing has been enacted.

There is no clear indication that the Trump administration will make any substantial changes in existing law on children and internet privacy. While federal agencies, including the Federal Trade Commission, could take the lead on protecting children online, there has been little public discussion of issues involving children and media access.

Trump’s choice for surgeon general, Janette Nesheiwat, said in 2024, “Social media has had a tremendous negative impact on all aspects of society, especially our younger generations.” It’s unclear how widely this view is shared within the new administration.

On other social media issues, such as the future of TikTok, Trump’s nominees and advisers have been divided. Particularly in an administration in which “the president owns a social media company, and one of his main associates owns another,” the future scope of federal action to protect children online is uncertain. This is likely to prompt states to advance laws that create more protections for children on social media.

Even though social media platforms have national and global reach, we believe that state-by-state leadership might be the best way to make laws in which the needs and rights of children and their families are seen, heard and protected.

Naomi Cahn is a professor of law at the University of Virginia. Leah A. Plunkett is a professor of law and associate dean of learning experience at Harvard University.

William Morgan: A watercolor thank you from New England

Painting by Dorothy Worden.

Posted on Jan. 31, 2025 in New England Diary (newenglanddiary.com)

English watercolor artist Dorothy Worden does not have much of an art historical presence – an Internet search turns up only that she was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1868, and she likely met her husband, the painter William E. Osborn, when they were both members of the vibrant early 20th-Century art colony at St Ives, in Cornwall. This Worden watercolor turned up for sale at the Acushnet River Antiques Mall, in New Bedford, priced at $45.

Given the sparseness of details of Worden’s life, we know nothing of any trips that she might have made to the United States. This scene, nevertheless, is indubitably rural New England, a village in the Berkshires or Vermont. And the watercolor is an unusual but clearly a very heartfelt note of gratitude. “Great Blessings … I am well, Thanks to you, and hope for an exhibition this coming year.”

Who was the Dr. Constantine, the dedicatee of the pastoral picture? The tone suggests that he was more than an emergency room doctor, maybe a psychiatrist, perhaps at one of the private clinics tucked in the hills of western New England, such as the Austin Riggs Center, in Stockbridge, Mass.

Painted, one would guess, in the 1920s or ‘30s, where has this picture been for almost a century? Did the healing doctor treasure this expression of thanks? It survived somehow, and made it to the seemingly inevitable estate sale, and then to the antiques mall. And now it has been purchased (I did not buy it), maybe to be framed and revered, a mild sort of adoration for a forgotten English painter. Or not.

A chronicler of things architectural in New England, William Morgan is the author of Monadnock Summer: the Architectural Legacy of Dublin, New Hampshire, and The Cape Cod Cottage, which will be published in March. He’s also the author of Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, which includes major examples of the style in New England.

‘Have you no sense of decency?’

Sen. Joseph McCarthy and his chief counsel, Roy Cohn, later to be the Trump family’s much feared chief lawyer and fixer.

Joseph N. Welch, partner at the Boston law firm of Hale & Dorr and Joseph McCarthy nemesis.

From the U.S. Senate Web site

June 9, 1954

Wisconsin Republican senator Joseph R. McCarthy rocketed to public attention in 1950 with his allegations that hundreds of Communists had infiltrated the State Department and other federal agencies. These charges struck a particularly responsive note at a time of deepening national anxiety about the spread of world communism.

McCarthy relentlessly continued his anticommunist campaign into 1953, when he gained a new platform as chairman of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. He quickly put his imprint on that subcommittee, shifting its focus from investigating fraud and waste in the executive branch to hunting for Communists. He conducted scores of hearings, calling hundreds of witnesses in both public and closed sessions.

A dispute over his hiring of staff without consulting other committee members prompted the panel's three Democrats to resign in mid-1953. Republican senators also stopped attending, in part because so many of the hearings were called on short notice or held away from the nation's capital. As a result, McCarthy and his chief counsel, Roy Cohn (later to be the Trump family’s chief lawyer and fixer and renown for his ruthlessness, corruption and hypocrisy) largely ran the show by themselves, relentlessly grilling and insulting witnesses. Harvard law dean Ervin Griswold described McCarthy's role as "judge, jury, prosecutor, castigator, and press agent, all in one."

In the spring of 1954, McCarthy picked a fight with the U.S. Army, charging lax security at a top-secret army facility. The army responded that the senator had sought preferential treatment for a recently drafted subcommittee aide. Amidst this controversy, McCarthy temporarily stepped down as chairman for the duration of the three-month nationally televised spectacle known to history as the Army-McCarthy hearings.

The army hired Boston lawyer Joseph Welch to make its case. At a session on June 9, 1954, McCarthy charged that one of Welch's attorneys had ties to a Communist organization. As an amazed television audience looked on, Welch responded with the immortal lines that ultimately ended McCarthy's career: "Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness." When McCarthy tried to continue his attack, Welch angrily interrupted, "Let us not assassinate this lad further, senator. You have done enough. Have you no sense of decency?"

Overnight, McCarthy's immense national popularity evaporated. Censured by his Senate colleagues, ostracized by his party, and ignored by the press, McCarthy died three years later, 48 years old and a broken man.

For more information: U.S. Congress. Senate. Executive Sessions of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations (McCarthy Hearings 1953-54), edited by Donald A. Ritchie and Elizabeth Bolling. Washington: GPO, 2003. S. Prt. 107-84. Available online.

On second thought, to hell with the whales

The ferry Nantucket at Oak Bluffs, on Martha’s Vineyard.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s "Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

In its last days, the Biden administration decided to block new rules that would have forced some ferries to Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket and Provincetown to be slowed to 11.5 miles an hour at certain times of the year to protect North Atlantic Right Whales, of which there are fewer than 400 left. Humans are driving them toward extinction, mostly via hitting them with boats and entangling them in fishing lines. It’s unknown how their extinction would affect the ecosystems of the waters off the New England coast.

Many rich people, from around America and beyond, like to go to Nantucket and The Vineyard, where they have hyper-expensive houses. Indeed, in the last half-century, the very rich have taken over much of the islands, which has made them unaffordable for many of the natives. The Vineyard is well known as a summer place for well-heeled Democrats, such as the Obamas. Joe Biden, for his part, has favored Nantucket, as do many Republican plutocrats.

Downhill skating

“Tamarack at Stratton” (oil on linen), by Jocelyn Sandor Urban, at Vermont Artisan Designs, Brattleboro.

Boston’s downtown plan gets some boos

Boston’s “Brutalist” City Hall.

From The Boston Guardian (New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

By Jules Roscoe

BOSTON

The city’s new Downtown zoning plan has yet another draft, this time with a new district along Washington Street that will allow buildings of up to 500 feet tall, and Downtown residents are not happy.

At a recent virtual public meeting, they berated Boston Planning Department (BPD) officials over the new PLAN: Downtown proposal, which they said all but scrapped six years of work by a city selected community and expert advisory board.

“When we were talking about PLAN:

Downtown, and we’ve been talking about it for six years, we were talking about 155 feet,” Martha McNamara, a preservationist who served on the advisory board, said in the meeting.

“What we now have is a strip of 500 feet that runs through the center of this historic and vibrant neighborhood. What this amendment tells me is that you have wasted my time.”

PLAN: Downtown originated in 2018 as a way to revitalize a neighborhood that had not been zoned since 1989. The new plan was intended to simplify the area to make it easier for developers, while preserving important historic landmarks and creating an inviting mixed-use district for residents.

Under the latest iteration of the zoning plan, released by Mayor Michelle Wu’s office on January 8, Downtown will have a new “SKY-R” district, which encompasses Washington and Stewart Streets. In this district, buildings are limited to a height of 155 feet, unless over 60 percent of building use is residential, in which case the maximum height is 500 feet. Housing was the Planning Department’s biggest selling point in the meeting.

“Key corridors like Washington Street can really support critical housing growth for the city,” senior planner Andrew Nahmias said in the meeting. “Overall, this [zone] is meant to reinforce the spine of Washington Street, while recognizing the sensitivity of some of the historic fabric there.”

Residents have until February 4 to comment on the draft. In the virtual meeting on January 15, however, they came out in full force. Attendance in the Zoom meeting hovered around 230 people, and the meeting lasted a full two hours. The most common concern was timing.

“With all due respect, this plan was dropped in our laps less than a week ago,” said Ryan St Marie, the manager of a luxury residential building that would be in the new SKY-R district. “This short time period is a slap in the face. I guarantee there would be 500 people on this call if you gave us proper notice. The fact that you’re giving us three weeks to respond, not appropriate.”

The other overwhelming concern among residents was that the new draft looked nothing like the previous iteration of the plan, issued last April. Rishi Shukla, the head of the Downtown Boston Residents’ Association who served on the advisory board, said that the previous plan had supported about 80 percent of what the board had suggested, but that the new plan looked nothing like it.

“The increase of height along the entirety of Washington Street was literally never contemplated because it was such a ridiculous notion, even back then,” Shukla said in a phone call. “The idea that we’re talking about that now as a solution is just. It’s a head scratcher.”

Kairos Shen, the head of the BPD since September, said he thought the current draft was a good compromise between the competing needs of developers and residents. Shen ran the planning department before the Walsh administration and was responsible for developing much of the Seaport.

“There’s been a lot of concern about some of the changes, and whether you will have enough time to actually review them,” Shen said at the end of the meeting. “So I’ve registered them. I think me being here tonight is representative of how serious we are taking the issues that have been raised.”

Two days after the meeting, the Planning Department announced it would hold another “office hours” meeting the next Wednesday for residents to voice more concerns.

“Within City Hall, my understanding from sources is this set off a bit of a firestorm internally,” Shukla said in a phone call. “Nobody was expecting the participation that they saw.”

God knows, most of us need it in these crazy times

“A Break from the Madness” (oil), by Kate Huntington in a group show opening Feb. 8, at Sitka Gallery, Newport, R.I.

Touro Synagogue, built in 1763. It’s the oldest existing synagogue in the United States.

Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

Llewellyn King: The struggle to save the printed word

Reading the July 21, 1969 Washington Post, before its coverage of the Watergate scandal made it very famous around the world.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The printed word is to be treasured.

Two decades ago, I would have written newspapers are to be treasured. But the morning newspaper of old — manufactured in a factory in the middle of the night, shoved onto a truck and trusted to a child for delivery — is largely over. It follows the demise of its predecessor, the afternoon newspaper. These fell to competition from television in the 1960s and 1970s.

The word nowadays is largely carried digitally, even though it might have the imprimatur of a print publication. All the really big names in print now have more virtual readers than traditional ones. These readers may never have the tactile enjoyment, the feel of “the paper” they read, but they read. Increasingly, I am one of those.

I plow through The Washington Post, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. I dip into The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph and the Financial Times.

I also read — and this is an interesting development — a number of magazines that are de facto dailies. These include The Economist, The New Yorker and The Spectator.

The Economist is the only publication to which I have a digital and a paper subscription.

Much as I have loved newspapers down through the years, I am resigned to the fact there will be fewer going forward, and a generation of young people will find them more a curiosity than anything else.

But the importance of the written word hasn’t diminished. I make the point about the written word — and I distinguish it purposely from the broadcast word — because it has staying power.

I have spent my entire career working on newspapers and making television programs. It is words that are written on paper or online that last, that are referenced down through time.

Overnight television has an impact, but it fades quickly; the advertising industry has scads of data on this. The printed word — using that term to embrace words on paper and online — has staying power.

People often remind me of something I wrote decades ago. Few remember something I said on television years ago. Or months ago. But people remember your face.

My regard for the printed word brings me to The Washington Post, where the news staff is aligned against the owner, Jeff Bezos.

There are two issues here.

The staff feels that Bezos has sold them out to President Donald Trump and the forces of MAGA.

Bezos bought the paper without any interest in being a newspaperman, in enjoying the pleasures and pain of news ownership. He didn’t understand that you don’t own a newspaper like you own a yacht.

A newspaper is a live, active, rambunctious and roiling thing. You have to enjoy the fray to own one. Hearst did, Pulitzer did, Murdoch did. You don’t retail words the way Amazon sells pizza crusts.

Not only must the newspaper proprietor deal with the news and its inherent controversies, but he or she also must deal with journalists, a breed apart, disinclined to any discipline besides deadlines. By nature and practice, they are opponents of authority.

The Post has been mostly untouched by Bezos, except for his decision to spike an editorial endorsing Vice President Kamala Harris in last year’s presidential race. The staff took it hard.

Bezos was undeterred and took what had become the billionaire’s pilgrimage to Mar-a-Lago to become, to staff fears, Trump’s liegeman, or at least to reassure Trump. Then Bezos got a seat at the inaugural.

Readers of The Post also took it hard and unsubscribed en masse. Thirty percent of those were among the critical digital subscriber ranks, indicating how political its readership is and just how difficult it is for the paper to please all the constituencies it must serve.

I was an assistant editor at The Post in the glory days of editor Ben Bradlee and the ownership of the pressure-resistant Graham family, under matriarch Katherine Graham. When I was at the paper, I was president of the Washington-Baltimore Newspaper Guild. The Guild negotiated what turned out to be the largest wage increase for journalists in any Guild contract. As I remember, it was 67 percent over three years.

Even so, the membership complained. The Post editors and writers are good at complaining with a high sense of self-regard. Len Downie, who was to rise to the executive editorship of the paper, declared, “King has sold us out.”

It was a contract that benefitted both the management of The Post and journalism in general.

It was a loud reminder of how poorly journalists are compensated and how this affects the flow of talent into the trade.

The driving force behind the contract from the union side was its professional head, the remarkably gifted Brian Flores and the equally gifted Guild chairman at The Post, John Reistrup.

Under Bezos, The Post first looked as though it would become a great force in the digital world, while the printed paper survived unspectacularly. Bezos clearly saw the digital potential.

But things unraveled and The Post started losing money. It lost $100 million last year.

It is still a good and maybe a great paper. But it needs to get its sense of mission back. That sense of mission can’t be at war with its owner.

The Post clearly would benefit from a new owner, but who has pockets deep enough and skin thick enough? It is a question Bezos and the querulous staff both need to ask themselves as the fate of the paper is uncertain.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island.

White House Chronicle

Counting birds on Nantucket

Bald eagle with its next meal. The species was one of those spotted in the Audubon Christmas Bird Count on Nantucket.

Text from an ecoRI News article

NANTUCKET, Mass. — The sharp, shrill call of a northern saw-whet owl was a welcome sound to the five people, including myself, standing on a soggy trail in the Nantucket State Forest at 5:45 on a chilly, drizzly December morning.

We had gone there specifically to hear the owl — we couldn’t see it, since the sun hadn’t quite risen yet — and log it for the 70th annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count on Nantucket. (If you can hear and identify a bird, you can count it, according to the rules.)

One of our team members for the count had suggested we meet before dawn and head to the state forest to see if we could hear the owl. She hung a small Bluetooth speaker on a tree limb and then played a recording of the owl’s calls. It didn’t respond to the first two, but when she played a third call, a sort of tooting sound, the owl replied. And kept tooting, as if it was delighted to hear a fellow owl.

It was an auspicious start to my first bird count, and it made me realize how seriously birders take the annual event, which has been taking place in the United States for more than 100 years.

Here’s the whole article.

Nantucket from a NASA satellite.

From Pennsylvania Dutch to '60’s graffiti to him

A item by Timothy Curtis in his show“Two Hundred Years of Painting,’’ at The Current, Stowe, Vt., through April 12.

Curtis, a Philadelphian, explores explore the relationships between Pennsylvania Dutch stoneware from the 19th Century, 1960s graffiti writing in the same area and his own artwork, highlighting the thread of influence in one region over 200 years. View original stoneware and new paintings by Curtis, along with a special area dedicated to celebrating the lives and work of 1960s African-American Philadelphia graffiti writers.

The Trapp Family Lodge, in Stowe, founded by the Austrian refugees from the Nazis whose story is the basis of the musical The Sound of Music

— Photo by Royalbroil

Chris Powell: Alphabet people needn’t be so terrified in Conn.

A six-band rainbow flag representing the LGBTQ community. The initials stand for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer or questioning.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Many people are terrified by Donald Trump’s return to the presidency, but perhaps none more so than members of sexual minorities, who lately have commandeered nine letters -- a third of the alphabet -- to construct an acronym with which to represent themselves. The other day an activist among Connecticut's alphabet people told The Hartford Courant that the political climate "continuously demonizes and degrades us" and that Trump wants "to legislatively and socially erase our community."

Really? Is there evidence for such claims, or do they just manifest paranoia, neurosis, hysteria and self-absorption?

For Connecticut isn't darkest South Carolina. To the contrary, it long has been quite libertarian about sexual identity.

In 1971 the state was among the first to repeal its ancient law criminalizing homosexual acts, a law that hadn’t been enforced for many years. To get rid of it little political courage was required from legislators.

In 1991 the state prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation.

In 2005 the state legalized same-sex "civil unions" and in 2008 same-sex marriage.

While some towns decline requests to fly the "pride flag" at town hall, it’s because the flag constitutes propagandizing for causes government hasn’t endorsed and most people oppose. This is not oppression.

As for Trump, while he, like most people, is against letting men who think of themselves as women participate in women's sports, he has not proposed anything to prevent people from presenting themselves as being of a gender that doesn't match their anatomy. Indeed, though Trump has gotten no credit for it, as a Democratic president would have gotten, his choice for treasury secretary, investment fund manager Scott Bessent, is a gay man married to another gay man, and they have two children.

They live in darkest South Carolina and have yet to be assassinated, and there have been no shrieks of outrage about Bessent from the MAGA crowd.

Trump will prohibit confining in women's prisons men who think of themselves as women, since such practice facilitates rape. But this isn't oppression either; it's safety for women prisoners.

Presumably Trump will oppose letting men use women's restrooms and vice versa, but this traditional policy for gender privacy doesn't obstruct anyone's access to a restroom. When you have to go, you have to go, and you always will be able to.

Amid Connecticut’s political correctness, the restroom issue has gone nutty here, with the General Assembly having required all public schools to put feminine-hygiene products in at least one male restroom. But even without that law, those products would be available in the school nurse's office, and furiously busy as the new president is, it may be a while before he worries about school restrooms in Connecticut.

The alphabet people profess to be terrified that Trump will get Congress to prohibit irreversible sex-change therapy for young people who suffer gender dysphoria. Of course many other people are terrified that some states still don't prohibit such therapy. But objection to it is not oppression but adherence to the principle that minors are not competent to make life-changing decisions. Nor should minors be pressured into such decisions by adults.

Besides, most young people seem to outgrow their gender dysphoria and many others come to regret their irreversible sex-change therapy. Such therapy should wait until young people turn 18.

So what’s left to terrify the alphabet people?

They often hold public rallies complaining of oppression and demanding respect, but the supposed oppressors never show up and nobody gets hurt. Nearly everyone who encounters the rallies passes by in libertarian indifference, the highest form of respect. The demonstrators are in more danger of getting hit by a drunken driver than by a "homophobe," a "transphobe," or a hysteria-phobe.

So the alphabet people should take the chips off their shoulders and live their lives as best they can. While some people could do without their braying, fewer people wish them harm than wish harm to Trump, and the alphabet offers another 17 letters with which they can continue searching for their authentic selves.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

The future is political

View in springtime of the Sherman, Conn., end of Candlewood Lake with Candlewood Mountain

“Opinions about the future of society are political opinions.’’

— Malcolm Crowley (1899-1989), American writer, editor, historian, poet and literary critic. He lived for much of his adult life in the exurban town of Sherman, Conn. It has lots of weekend people from New York City.

Good but stern

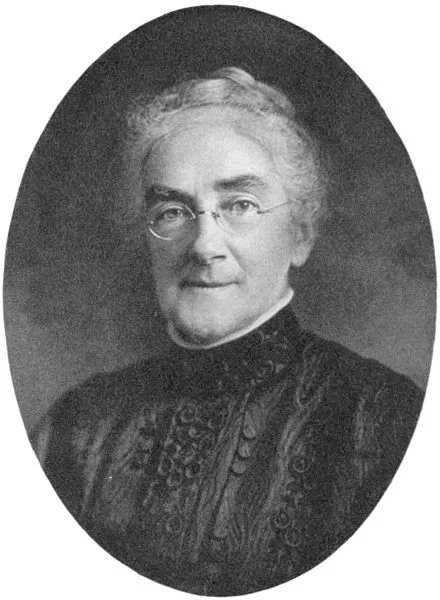

Ellen Swallow Richards in the 1890’s.

“New England is the home of all that is good and noble with all her sternness and uncompromising opinions.’’

Ellen Swallow Richards (1842-1911), industrial engineer and environmental chemist. She was a native of Dunstable, Mass.

Work-life balance

“Two Women on a Jack” (detail), (metal, tin, wire, wood, and ratcheting jack components), by June Leaf, at the Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover,Mass. (private collection)

— Courtesy Hyphen, New York

Gary W. Rohe: How climate-related insurance woes could break the economy

Photo from roof of high rise in Downtown Los Angeles of Pacific Palisades Fire at peak intensity

Toastt21 photo

MDDDLETOWN, Conn.

The devastating wildfires in Los Angeles have made one threat very clear: Climate change is undermining the insurance systems American homeowners rely on to protect themselves from catastrophes. This breakdown is starting to become painfully clear as families and communities struggle to rebuild.

But another threat remains less recognized: This collapse could pose a threat to the stability of financial markets well beyond the scope of the fires.

It’s been widely accepted for more than a decade that humanity has three choices when it comes to responding to climate risks: adapt, abate or suffer. As an expert in economics and the environment, I know that some degree of suffering is inevitable — after all, humans have already raised the average global temperature by 1.6 degrees Celsius, or 2.9 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s why it’s so important to have functioning insurance markets.

While insurance companies are often cast as villains, when the system works well, insurers play an important role in improving social welfare. When an insurer sets premiums that accurately reflect and communicate risk — what economists call “actuarially fair insurance” — that helps people share risk efficiently, leaving every individual safer and society better off.

But the scale and intensity of the Southern California fires — linked in part to climate change, including record-high global temperatures in 2023 and again in 2024 — has brought a big problem into focus: In a world impacted by increasing climate risk, traditional insurance models no longer apply.

How climate change broke insurance

Historically, the insurance system has worked by relying on experts who study records of past events to estimate how likely it is that a covered event might happen. They then use this information to determine how much to charge a given policyholder. This is called “pricing the risk.”

Many California wildfire survivors face insurance struggles, as this CBS Evening News report shows.

When Americans try to borrow money to buy a home, they expect that mortgage lenders will make them purchase and maintain a certain level of homeowners insurance coverage, even if they chose to self-insure against unlikely additional losses. But thanks to climate change, risks are increasingly difficult to measure, and costs are increasingly catastrophic. It seems clear to me that a new paradigm is needed.

California provided the beginnings of such a paradigm with its Fair Access to Insurance program, known as FAIR. When it was created in 1968, its authors expected that it would provide insurance coverage for the few owners who were unable to get normal policies because they faced special risks from exposure to unusual weather and local climates.

But the program’s coverage is capped at US$500,000 per property – well below the losses that thousands of Los Angeles residents are experiencing right now. Total losses from the wildfires’ first week alone are estimated to exceed $250 billion.

How insurance could break the economy

This state of affairs isn’t just dangerous for homeowners and communities — it could create widespread financial instability. And it’s not just me making this point. For the past several years, central bankers at home and abroad have raised similar concerns. So let’s talk about the risks of large-scale financial contagion.

Anyone who remembers the Great Recession of 2007-2009 knows that seemingly localized problems can snowball.

In that event, the value of opaque bundles of real estate derivatives collapsed from artificial and unsustainable highs, leaving millions of mortgages around the U.S. “underwater.” These properties were no longer valued above owners’ mortgage liabilities, so their best choice was simply to walk away from the obligation to make their monthly payments.

Lenders were forced to foreclose, often at an enormous loss, and the collapse of real estate markets across the U.S. created a global recession that affected financial stability around the world.

Forewarned by that experience, the U.S. Federal Reserve Board wrote in 2020 that “features of climate change can also increase financial system vulnerabilities.” The central bank noted that uncertainty and disagreement about climate risks can lead to sudden declines in asset values, leaving people and businesses vulnerable.

At that time, the Fed had a specific climate-based example of a not-implausible contagion in mind – global risks from sudden large increases in global sea level rise over something like 20 years. A collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could create such an event, and coastlines around the world would not have enough time to adapt.

In a 2020 press conference, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell discusses climate change and financial stability.

The Fed now has another scenario to consider – one that’s not hypothetical.

It recently put U.S. banks through “stress tests” to gauge their vulnerability to climate risks. In these exercises, the Fed asked member banks to respond to hypothetical but not-implausible climate-based contagion scenarios that would threaten the stability of the entire system.

We will now see if the plans borne of those stress tests can work in the face of enormous wildfires burning throughout an urban area that’s also a financial, cultural and entertainment center of the world.

Gary W. Rohe is a professor of economics and environmental studies at Wesleyan University.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment

Climate change