Chris Powell: Minimizing college arrogance, hypocrisy; take on liquor-store lobby

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Gov. Ned Lamont is right that the expense-account exploitation perpetrated by the chancellor of the Connecticut State Colleges and Universities system, Terrence Cheng, and his fellow top administrators is "small ball," insofar as the financial expense goes. It doesn't compare to the hundreds of millions of dollars in cost overruns incurred in the New London state pier project by the Connecticut Port Authority, which haven't offended the governor either.

Even so, there is much to be offended about in the CSCU system, and it goes beyond Cheng's awarding himself the perks of royalty on top of a salary and benefit package worth a half million dollars annually while constantly pleading poverty for the higher education system, which chronically operates at a deficit and is always asking for more money.

Cheng's arrogance and hypocrisy are not "small ball" but major-league.

So is the unaccountability of the college system, which is supposed to answer to its 15-member Board of Regents. While the board includes former state House Speaker Richard J. Balducci, a Democrat, and New Britain Mayor Erin Stewart, a Republican who may run for governor, it did not rush to investigate when Connecticut's Hearst newspapers exposed Cheng's exploitation of his expense account. Instead the governor had to ask state Comptroller Sean Scanlon to investigate, apparently assuming that the Board of Regents is just for show and its members are airheads. (The governor might know, since most of the regents are his appointees.)

The regents have escaped critical questioning not just by the governor and the comptroller but also by news organizations covering the expense-account scandal. How did the regents fail to learn how Cheng and his gang were abusing their expense accounts while pleading the college system's poverty? If Cheng and his gang weren't reporting to the regents, to whom were they reporting? Who was supposed to supervise their expense claims? Apparently no one.

How do the regents justify the half million dollars in compensation conferred on Cheng every year? What is so special about his leadership? Why do they continue to let Cheng live out of state, far from his workplace? What do the regents think about the example Cheng gang has set?

The regents are off the hook until someone bothers to ask.

Having decided to minimize the scandal, the governor probably won't be asking.

The leaders of the Republican minority in the General Assembly, Sen. Stephen Harding, of Brookfield, and Rep. Vincent J. Candelora, of North Branford, declared that Cheng should be fired, but Democratic legislators said only that they'd welcome proposals for tighter standards for purchases by college administrators. The arrogance, hypocrisy and bad examples of the administrators seem not to bother the Democratic legislators any more than they bother the governor.

During the legislature's budget deliberations in a few weeks will the Democrats even remember the high living of the Cheng gang when they show up again to ask for more money?

BREAK THE LIQUOR LOBBY: When the legislature convenes next month Connecticut's supermarkets again may ask to be allowed to sell wine along with the beer they already sell. Most state residents would like the convenience, which is enjoyed in 42 other states. Again the problem will be the liquor stores and particularly the "mom and pop" stores, which fear that ordinary free-market competition will put them out of business.

So what if it does? Supermarkets and other retailers in Connecticut fail and close all the time and no legislators propose to restrict competition in those businesses. But the liquor stores purport to be special and to deserve protection against competition. They get this protection not only through the ban on supermarket sales of wine but also through the state's grotesque system of minimum prices for alcoholic beverages, which assures retailers a profit and customers high prices.

Most legislative districts have at least several "mom and pops" and statewide they form a powerful lobby against the public interest in more competition and lower prices. Will legislators dare to stand up against this special interest next year?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Hatchlings’ show brightens Boston’s winter

“Hatchlings’’ at Boston’s Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway.

Edited from a Boston Guardian report by Brandon Hill

(New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

“Hatchlings,’’ Boston’s captivating winter lights installation created by interdisciplinary design team Studio HHH first graced The Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway last winter, lighting up the park with vibrant, animated arches that offer a playful nod to one of Boston’s most iconic landmarks, the Hatch Shell on the Esplanade.

“Hatchlings” brings to life the whimsical idea of the Hatch Shell "hatching" a series of baby shells that wander off along the Greenway like a multicolored parade of ducklings. This year, the installations have expanded from seven to nine mini-Hatch Shell structures scattered across the park, including a new arrangement of three “Hatchlings’’ in a single space, creating a primary destination for visitors near the summer site of the Trillium Beer Garden. The smallest measures 2.5 feet, while the largest reaches 8.5 feet tall. The bright, joyful display invites visitors to engage with the park in a new way, serving as an interactive photo backdrop and a perfect spot for informal gatherings.

“We really loved the challenge of creating an experience specific to Boston’s identity,” said Vanessa Till Hooper, founder and creative director of Studio HHH.

“The Hatch Shell design has these wood baffles that bounce the sound from the stage out into the grassy area in front of it. Those angles are what we were replicating in the weaving of the lights to mimic those baffled angles. So, what you see in wood in the Hatch Shell is what you see in the lights in the “Hatchlings.”

Each “Hatchling” is powered by solar energy, a symbolic aspect of the artwork that functions as a model of smart implementation of solar energy even in the darker winter months. “Sustainability these days is so much about awareness and also proving that things are possible,” Till Hooper said. “It was a mission for us to prove that it was possible to do a winter lights installation that had a solar element and really showcasing it as an opportunity for other people to consider the use of solar in their holiday lights.”

This year’s setup is about 50/50 solar and hybrid energy. With some of the installations relying entirely on solar energy, some entirely on the grid, but mostly a hybrid mix.

Initially, the “Hatchlings” were intended to be small performance spaces to book live music or throw impromptu performances, but the studio quickly learned last year that the public wanted to engage with the structures more directly. They moved performances to be adjacent to the ”Hatchlings,’’ opening up the structures as a collection of Boston’s brightest holiday photo backdrops.

The “Hatchlings” will remain on display until February.

‘The toys did it’

Text from The New England Historical Society

“In 1918, America was at war. The country needed to devote all of its industrial might to victory in Europe. A war council considered banning all toy production and prohibiting gift-giving at Christmas. It took A.C. Gilbert, inventor of the Erector Set, to save Christmas.

“Gilbert led a remarkable life. He was a medical doctor, an Olympic gold medal winner, a magician, a toy millionaire, a big-game hunter and, most of all, a kid at heart.

“He wore old gabardine suits and rubber soled shoes, and he always carried a pipe that he sometimes stuck into his pocket while lit. In late October 1918, he brought a satchel full of educational toys to Washington, D.C., and let a room full of Cabinet secretaries play with them.

“He persuaded them that children needed toys because the nation needed scientists and engineers. The war council decided to give Santa free rein after all.

“‘The toys did it, Gilbert said.’’

It’s a living

“The Maine Lobsterman,’’ in Lobsterman Park, Portland. Standing at the intersection of Middle Street and Temple Street, it was sculpted by Victor Kahill.

“I conversed with a young lobster fisherman who gets up at 5 in the morning and goes home again from the sea at 3 in the afternoon. I asked him if he liked lobstering. ‘You get used to it’ was his reply.’’

—From Back Roads of New England (1974), by Earl Thollander

The white stuff

“Whispers of Winter” (oil on canvas), by Louie Pisterzi, in the “Let There Be Love’’ show at Spectrum Art Gallery, Centerbrook, Conn., through Jan. 11

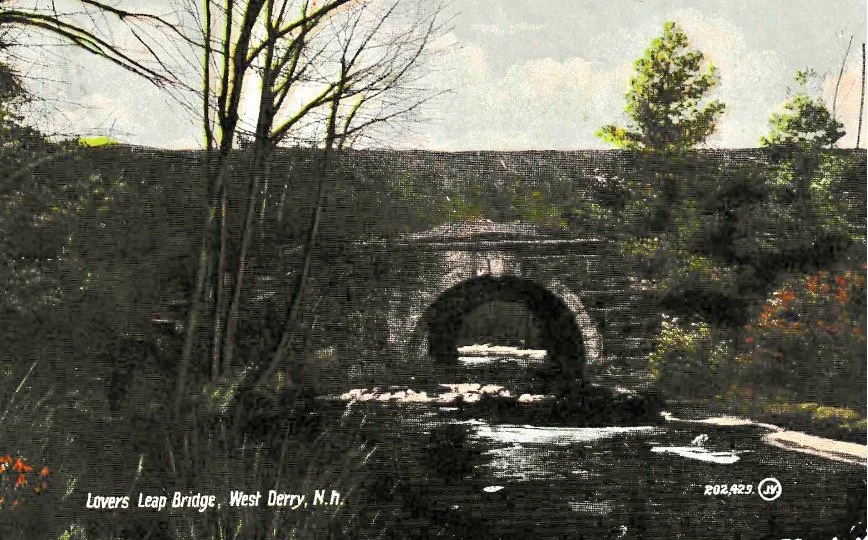

William Morgan: Postcard of assignation?

Unlike the usual old postcard finds, with their recitation of visiting the scene on the front of the missive, this one, sent 114 years ago to Fred P. McFarland in the New Hampshire town of Raymond, offers both a bit of mystery and a hint of romance. The unnamed sender, M.––––, got across quite a bit of information, along with the hint of a possible tryst. Compared to a contemporary Facebook post, an e-mail, or a text, the writer managed to convey considerable private meaning in a very public medium.

The attractive but hardly remarkable bridge depicted here is labeled Lovers Leap, while the one-cent stamp is attached upside down – in my day the inverted postage was used only on mail to girlfriends.

While chest-nutting is probably not a code for some other more physical activity, Miss M.––––suggests meeting at Lizzie Seavy’s for a husking bee. An article on husking bees in the Dakotas at the same period notes the beyond-harvest courting aspect of peeling corn stalks: a red ear of corn discovered by a girl could be a gift to her beau, but if a boy found a red ear, he was allowed to kiss the object of his affections. I would hesitate to speculate on the meaning of Fred’s “working hard.”

The seemingly forward and determined M.–––– was also confident in the postoffice’s ability to deliver her card by the next day, in time for Fred to decide if he wanted to go husking. Some postcards nowadays might take weeks to be delivered.

William Morgan is a Providence-based writer and photographer. As a chronicler of New England art, especially architecture, he has contributed to such publications at The Boston Globe, The Providence Journal, The Hartford Courant and The Portland Press-Herald

From the plain to the hills

The green area between the uplands — now the Connecticut River Valley — used to be a huge lake that formed about 15,000 years ago as the Ice Age receded.

Merry ink on paper

One of the first American Christmas cards, printed circa 1874. It was created by the Boston-based business of Louis Prang (1824-1909), Prussian-American printer, lithographer and publisher. He is sometimes called the "father of the American Christmas card.’’

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

The (physical) Christmas card tradition can sometimes be a bit weird. You get cards from people you haven’t actually seen in many years. Sometimes they’re accompanied by narratives presenting what’s been happening with relatives and close friends of the senders – often as folded inserts in the card envelopes with listings of achievements – graduations, fancy new jobs, prizes – and less so, sad news, especially of deaths and illness. Sometimes they’re weirdly intimate considering the length of time since you’ve seen or talked with the writers.

You might never again get a phone call or a visit from some of these senders. The next word you might get about them might be their obituaries.

My approach has always been to reply, in ink on paper, with a card to anyone who has taken the time to send one, no matter how long ago it was that I saw the senders. That’s not just because it’s courteous but because you never know what you might learn by maintaining these relationships, however tenuous they may seem. It’s a kind of yearly discipline, and you can look at the cards over the years as a kind of social history.

Some may complain about your handwriting (my arthritic hands too often produce a scrawl), but most people like the proof of personality and physicality, however flawed.

Block-sending Christmas cards by email can be a little chilly and sterile. But then, many people are fired by email and text these days. No wonder anomie is advancing.

How to make your rooms bigger

From the current show “The Art of French Wallpaper Design,’’ at the Museum of Art at the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence.

Peter C. Mancall: Why the Puritans opposed Christmas

“The Puritan,’’ by Augustus Saint Gaudens, in Springfield, Mass.

‘When winter settles in across the U.S., the alleged “War on Christmas” heats up.

In recent years, department store greeters and Starbucks cups have sparked furor by wishing customers “happy holidays.” This year, with state officials warning of holiday gatherings becoming superspreader events in the midst of a pandemic, opponents of some public health measures to limit the spread of the pandemic are already casting them as attacks on the Christian holiday.

But debates about celebrating Christmas go back to the 17th Century. The Puritans, it turns out, were not too keen on the holiday. They first discouraged Yuletide festivities and later outright banned them.

At first glance, banning Christmas celebrations might seem like a natural extension of a stereotype of the Puritans as joyless and humorless that persists to this day.

But as a scholar who has written about the Puritans, I see their hostility toward holiday gaiety as less about their alleged asceticism and more about their desire to impose their will on the people of New England – Natives and immigrants alike.

The earliest documentary evidence for their aversion to celebrating Christmas dates back to 1621, when Gov. William Bradford of Plymouth Colony castigated some of the newcomers who chose to take the day off rather than work.

But why?

As a devout Protestant, Bradford did not dispute the divinity of Jesus Christ. Indeed, Puritans spent a great deal of time investigating their own and others’ souls because they were so committed to creating a godly community.

Bradford’s comments reflected Puritans’ lingering anxiety about the ways that Christmas had been celebrated in England. For generations, the holiday had been an occasion for riotous, sometimes violent behavior. The moralist pamphleteer Phillip Stubbes believed that Christmastime celebrations gave celebrants license “to do what they lust, and to folow what vanitie they will.” He complained about rampant “fooleries” like playing dice and cards and wearing masks.

Civil authorities had mostly accepted the practices because they understood that allowing some of the disenfranchised to blow off steam on a few days of the year tended to preserve an unequal social order. Let the poor think they are in control for a day or two, the logic went, and the rest of the year they will tend to their work without causing trouble.

English Puritans objected to accepting such practices because they feared any sign of disorder. They believed in predestination, which led them to search their own and others’ behavior for signs of saving grace. They could not tolerate public scandal, especially when attached to a religious moment.

Puritan efforts to crack down on Christmas revelries in England before 1620 had little impact. But once in North America, these seekers of religious freedom had control over the governments of New Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay and Connecticut.

Boston became the focal point of Puritan efforts to create a society where church and state reinforced each other.

The Puritans in Plymouth and Massachusetts used their authority to punish or banish those who did not share their views. For example, they exiled an Anglican lawyer named Thomas Morton who rejected Puritan theology, befriended local Indigenous people, danced around a maypole and sold guns to the Natives. He was, Bradford wrote, “the Lord of Misrule” – the archetype of a dangerous type who Puritans believed create mayhem, including at Christmas.

In the years that followed, the Puritans exiled others who disagreed with their religious views, including Anne Hutchinson and Roger Williams who espoused beliefs deemed unacceptable by local church leaders. In 1659, they banished three Quakers who had arrived in 1656. When two of them, William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson, refused to leave, Massachusetts authorities executed them in Boston.

This was the context for which Massachusetts authorities outlawed Christmas celebrations in 1659. Even after the statute left the law books in 1681 during a reorganization of the colony, prominent theologians still despised holiday festivities.

In 1687, the minister Increase Mather, who believed that Christmas celebrations derived from the bacchanalian excesses of the Roman holiday Saturnalia, decried those consumed “in Revellings, in excess of wine, in mad mirth.”

The hostility of Puritan clerics to celebrations of Christmas should not be seen as evidence that they always hoped to stop joyous behavior. In 1673, Mather had called alcohol “a good creature of God” and had no objection to moderate drinking. Nor did Puritans have a negative view of sex.

What the Puritans did want was a society dominated by their views. This made them eager to convert Natives to Christianity, which they managed to do in some places. They tried to quash what they saw as usurious business practices within their community, and in Plymouth they executed a teenager who had sex with animals, the punishment prescribed by the Book of Leviticus. When the Puritans believed that Indigenous people might attack them or undermine their economy, they lashed out – most notoriously in 1637, when they set a Pequot village on fire, murdered those who tried to flee and sold captives into slavery.

By comparison to their treatment of Natives and fellow colonists who rebuffed their unbending vision, the Puritan campaign against Christmas seems tame. But it is a reminder of what can happen when the self-righteous control the levers of power in a society and seek to mold a world in their image.

Peter C. Mancall is the Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities at the University of Southern California.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

A taste for the foreign

“31 Flavors Invading Japan/Today’s Special,’’ by Masami Teraoka, in the show “Im/Perfect Modernisms: Asian Art and Identity Since 1945,’’at the Worcester Art Museum, through Jan. 20.

The museum says:

“Challenge your preconceptions of modern art through thought-provoking and at times subversive artworks created across postwar Asia.’’

Llewellyn King: Trying to censor stressed news media via lawsuits

Photojournalists and President Obama in 2014.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is a lot of dither about the future of journalism. Make no mistake, it is an essential commodity.

If you know what is going on in Gaza, Ukraine or Syria, it is because brave journalists told you. Not the government, not some academic institution, not artificial intelligence, and not hearsay from your friends or from a political party.

The crisis in journalism isn’t that it failed analytically in last election, or that we — an irregular army of individualists — failed, but that journalism has run out of money and its political enemies have found that the courts (and the fear of libel prosecution) can terrorize the companies that own the media.

In 2016 the gossipy site, Gawker, was sued by the pro wrestler and political figure Hulk Hogan. The lawsuit was financed by the billionaire investor Peter Thiel.

Now come two suits, filed by President-elect Donald Trump: One which he won against ABC News, and one just filed against the Des Moines Register. It is reported that conservative interests plan a series of these legal interventions against the media.

This will have a frightening impact on news coverage. When there is fear of prosecution, there is less likely to be investigative news coverage.

So far, the most troublesome of the prosecutions has been the one against ABC News. The network caved in early. It agreed to pay $15 million plus legal fees into a fund for what will be the first Trump presidential library.

Could it be that ABC is owned by Disney, and Disney wants good relations with the incoming administration?

But a much bigger problem faces the media than the fear of prosecution. It is that the old media, led by local and regional newspapers, are dying and although there are thousands of podcasts, they don’t take up the slack.

You could listen to an awful lot of podcasts and not know what is going on. State houses and local courts aren’t being covered. The sanitizing effect of press surveillance has been withdrawn and, frankly, God help the poor defendants in a local court where there is a disproportionate desire to plead cases, to avoid honest trials even when there is conspicuous doubt.

I never tire of repeating what Dan Raviv, former CBS News correspondent, said to me once, “My job is simple. I try to find out what is going on and tell people.”

Quite so. But there is a problem: Journalism needs to be concentrated in a newspaper or a broadcast outlet where there is enough revenue to do the job. Otherwise, you get what I think of as the upside-down pyramid of more and more commentary, based on less and less reporting.

We are awash in commentary, some of it very good and some of it trash. But it is all based on news gathered by those news organizations that can afford to employ a phalanx of reporters.

Regional newspapers used to have their own Washington bureaus and their own foreign bureaus. At one time, The Baltimore Sun had 12 overseas bureaus. Now it has none.

This is the story across the country. Fewer people actually cover the news, digging, checking and telling us what they have found out.

Throughout the history of journalism, technology has been disruptive, sometimes advantageously and sometimes less so. Modern printing presses developed at the end of the 19th Century were important boosters, as was the invention of the Linotype machine, in 1884.

On the negative side, television killed off evening papers and podcasts are taking a toll on radio. Now the Internet and the tech companies — Google, Facebook, et al. — have siphoned off most of the revenue that supported newspapers, radio and television.

As one can’t have a free and fair society without vibrant journalism, we clearly need a new paradigm that is Internet-based news organizations that are large enough and rich enough to do the job in the time-honored way with reporters asking questions, whether it is at the courthouse, the White House, or on the battlefield.

There is a clear choice: News and informed analysis or rumor and conspiracy.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Circle route

“Subtle and Strong” (steel), by Margaret Jacobs, in her show at 3S Artspace, Portsmouth, N.H. She develops organic textures and surfaces.

Market Square, Portsmouth, in 1853

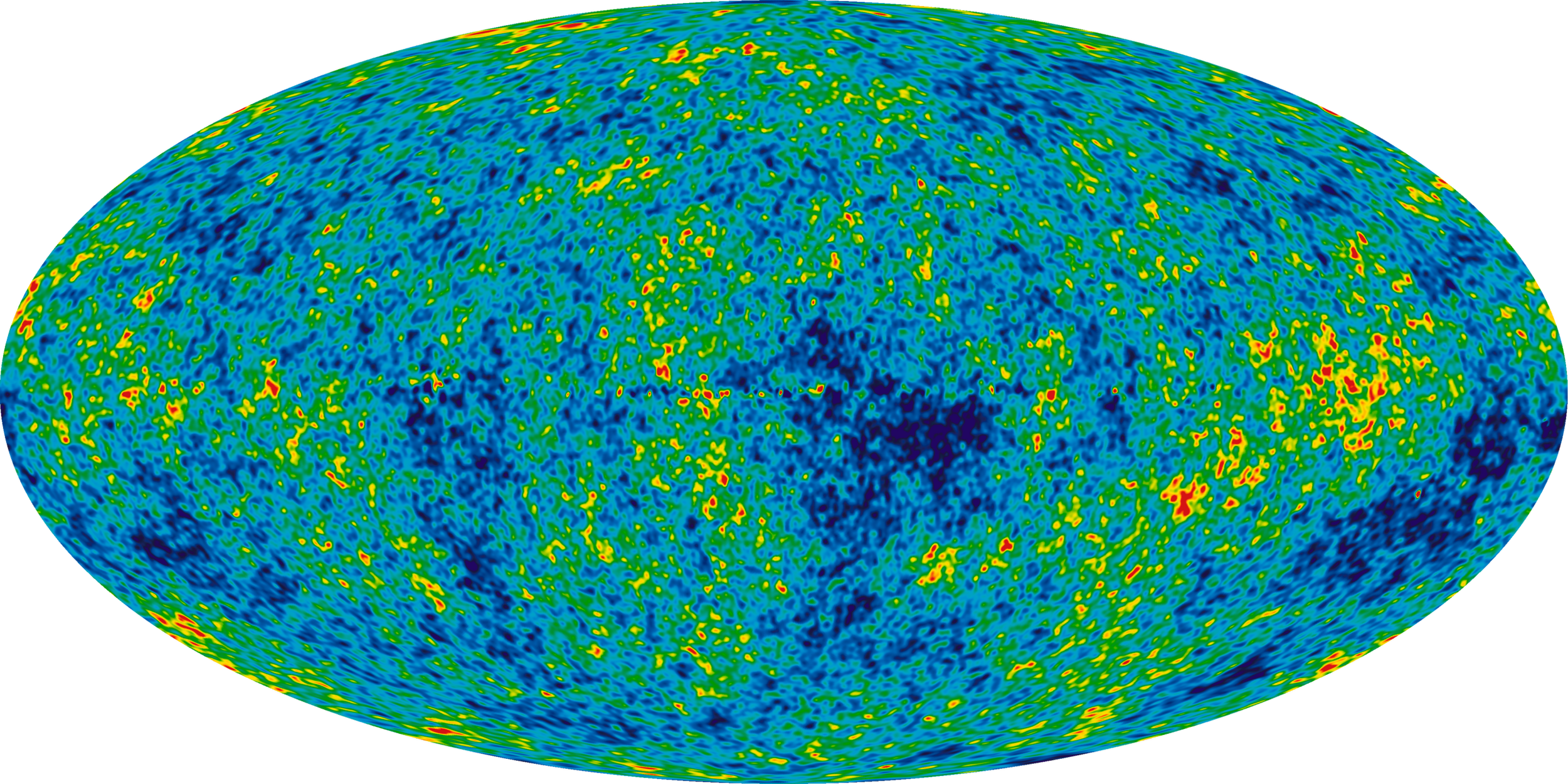

Nicole Granucci: What is the universe expanding into?

HAMDEN, Conn.

When you bake a loaf of bread or a batch of muffins, you put the dough into a pan. As the dough bakes in the oven, it expands into the baking pan. Any chocolate chips or blueberries in the muffin batter become farther away from each other as the muffin batter expands.

The expansion of the universe is, in some ways, similar. But this analogy gets one thing wrong – while the dough expands into the baking pan, the universe doesn’t have anything to expand into. It just expands into itself.

The universe expands like a baking muffin. The objects in space move farther apart, with more space between them. UChicago Creative

It can feel like a brain teaser, but the universe is considered everything within the universe. In the expanding universe, there is no pan. Just dough. Even if there were a pan, it would be part of the universe and therefore it would expand with the pan.

Even for me, a teaching professor in physics and astronomy who has studied the universe for years, these ideas are hard to grasp. You don’t experience anything like this in your daily life. It’s like asking what direction is farther north of the North Pole.

Another way to think about the universe’s expansion is by thinking about how other galaxies are moving away from our galaxy, the Milky Way. Scientists know the universe is expanding because they can track other galaxies as they move away from ours. They define expansion using the rate that other galaxies move away from us. This definition allows them to imagine expansion without needing something to expand into.

The expanding universe

The universe started with the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago. The Big Bang describes the origin of the universe as an extremely dense, hot singularity. This tiny point suddenly went through a rapid expansion called inflation, where every place in the universe expanded outward. But the name Big Bang is misleading. It wasn’t a giant explosion, as the name suggests, but a time where the universe expanded rapidly.

The universe then quickly condensed and cooled down, and it started making matter and light. Eventually, it evolved to what we know today as our universe.

The idea that our universe was not static and could be expanding or contracting was first published by the physicist Alexander Friedman in 1922. He confirmed mathematically that the universe is expanding.

While Friedman proved that the universe was expanding, at least in some spots, it was Edwin Hubble who looked deeper into the expansion rate. Many other scientists confirmed that other galaxies are moving away from the Milky Way, but in 1929, Hubble published his famous paper that confirmed the entire universe was expanding, and that the rate it’s expanding at is increasing.

This discovery continues to puzzle astrophysicists. What phenomenon allows the universe to overcome the force of gravity keeping it together while also expanding by pulling objects in the universe apart? And on top of all that, its expansion rate is speeding up over time.

Many scientists use a visual called the expansion funnel to describe how the universe’s expansion has sped up since the Big Bang. Imagine a deep funnel with a wide brim. The left side of the funnel – the narrow end – represents the beginning of the universe. As you move toward the right, you are moving forward in time. The cone widening represents the universe’s expansion.

The expansion funnel visually shows how the universe’s rate of expansion has increased over time. At the left of the funnel is the Big Bang, and since then, the universe has expanded at a faster and faster rate. NASA

Scientists haven’t been able to directly measure where the energy causing this accelerating expansion comes from. They haven’t been able to detect it or measure it. Because they can’t see or directly measure this type of energy, they call it dark energy.

According to researchers’ models, dark energy must be the most common form of energy in the universe, making up about 68% of the total energy in the universe. The energy from everyday matter, which makes up the Earth, the Sun and everything we can see, accounts for only about 5% of all energy.

Dark matter and dark energy make up most of the universe. Green Bank Observatory, CC BY-NC-ND

Outside the expansion funnel

So, what is outside the expansion funnel?

Scientists don’t have evidence of anything beyond our known universe. However, some predict that there could be multiple universes. A model that includes multiple universes could fix some of the problems scientists encounter with the current models of our universe.

One major problem with our current physics is that researchers can’t integrate quantum mechanics, which describes how physics works on a very small scale, and gravity, which governs large-scale physics.

The rules for how matter behaves at the small scale depend on probability and quantized, or fixed, amounts of energy. At this scale, objects can come into and pop out of existence. Matter can behave as a wave. The quantum world is very different from how we see the world.

At large scales, which physicists call classical mechanics, objects behave how we expect them to behave on a day-to-day basis. Objects are not quantized and can have continuous amounts of energy. Objects do not pop in and out of existence.

The quantum world behaves kind of like a light switch, where energy has only an on-off option. The world we see and interact with behaves like a dimmer switch, allowing for all levels of energy.

But researchers run into problems when they try to study gravity at the quantum level. At the small scale, physicists would have to assume gravity is quantized. But the research many of them have conducted doesn’t support that idea.

An infinitely expanding universe lies beyond the Milky Way galaxy. DECaPS2/DOE/FNAL/DECam/CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA, M. Zamani & D. de Martin via AP

One way to make these theories work together is the multiverse theory. There are many theories that look beyond our current universe to explain how gravity and the quantum world work together. Some of the leading theories include string theory, brane cosmology, loop quantum theory and many others.

Regardless, the universe will continue to expand, with the distance between the Milky Way and most other galaxies getting longer over time.

Nicole Granucci is a physics instructor at Quinnipac University, in Hamden, Conn.

She does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond her academic appointment.

Martha Bebinger: Boston hospital turns to solar to help patients pay utility bills

Moakley Building at Boston Medical Center from Harrison Avenue

Drknchkn photo

Text from Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

BOSTON

Anna Goldman, a primary-care physician at Boston Medical Center, got tired of hearing that her patients couldn’t afford the electricity needed to run breathing-assistance machines, recharge wheelchairs, turn on air conditioning, or keep their refrigerators plugged in. So she worked with her hospital on a solution.

The result is a pilot effort called the Clean Power Prescription program. The initiative aims to help keep the lights on for roughly 80 patients with complex, chronic medical needs.

The program relies on 519 solar panels installed on the roof of one of the hospital’s office buildings. Half the energy generated by the panels helps power the medical center. The rest goes to patients who receive a monthly credit of about $50 on their utility bills.

Kiki Polk was among the first recipients. She has a history of Type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure.

On a warm fall day, Polk, who was nine months pregnant at the time, leaned into the air-conditioning window unit in her living room.

“Oh my gosh, this feels so good, baby,” Polk crooned, swaying back and forth. “This is my best friend and my worst enemy.”

An enemy, because Polk can’t afford to run the AC. On cooler days, she has used a fan or opened a window instead. Polk knew the risks of overheating during pregnancy, including added stress on the pregnant person’s heart and potential risks to the fetus. She also has a teenage daughter who uses the AC in her bedroom — too much, according to her mom.

Kiki Polk, one of the first Boston Medical Center patients to enroll in the Clean Power Prescription program, turns on the air conditioner in her home in the city’s Dorchester neighborhood. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)

Polk got behind on her utility bill. Eversource, her electricity provider, worked with her on a payment plan. But the bills were still high for Polk, who works as a school-bus and lunchroom monitor. She was surprised when staff at Boston Medical Center, where she was a patient, offered to help.

“I always think they’re only there for, you know, medical stuff,” Polk said, “not the personal financial stuff.”

Polk is on maternity leave now to care for her baby, the tiny Briana Moore.

Goldman, who is also BMC’s medical director of climate and sustainability, said hospital screening questionnaires show thousands of patients like Polk struggle to pay their utility bills.

“I had a conversation recently with someone who had a hospital bed at home,” Goldman said. “They were using so much energy because of the hospital bed that they were facing a utility shut-off.”

Goldman wrote a letter to the utility company requesting that the power stay on. Last year, she and her colleagues at Boston Medical Center wrote 1,674 letters to utility companies asking them to keep patients’ gas or electricity running. Goldman took that number to Bob Biggio, the hospital’s chief sustainability and real estate officer. He’d been counting on the solar panels to help the hospital shift to renewable energy, but sharing the power with patients felt as if it fit the health system’s mission.\

“Boston Medical Center’s been focused on lower-income communities and trying to change their health outcomes for over 100 years,” Biggio said. “So this just seemed like the right thing to do.”

Standing on the roof amid the solar panels, Goldman pointed out a large vegetable garden one floor down.

“We’re actually growing food for our patients,” she said. “And, similarly, now we are producing electricity for our patients as a way to address all of the factors that can contribute to health outcomes.”

Many hospitals help patients sign up for electricity or heating assistance because research shows that not having them increases respiratory problems, mental distress and makes it harder to sleep. Aparna Bole, a pediatrician and senior consultant in the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity at the federal Department of Health and Human Services, said these are common problems for low- and moderate-income patients. BMC’s approach to solving them may be the first of its kind, she said.

“To be able to connect those very patients with clean, renewable energy in such a way that reduces their utility bills is really groundbreaking,” Bole said.

Bole is using a case study on the solar credits program to show other hospitals how they might do something similar. Boston Medical Center officials estimate the project cost $1.6 million, and said 60% of the funding came from the federal Inflation Reduction Act. Biggio has already mapped plans for an additional $11 million in solar installations.

“Our goal is to scale this pilot and help a lot more patients,” he said.

The expansion he envisions would allow a tenfold increase in patients who could be served by the program, but it still would not meet the demand. For now, each patient in the pilot program receives assistance for just one year. Boston Medical Center is looking for partners who might want to share their solar energy with the hospital’s patients in exchange for a higher federal tax credit or reimbursement.

Eversource’s vice president for energy efficiency, Tilak Subrahmanian, said the pilot was a complex project to launch, but now that it’s in place, it could be expanded.

“If other institutions are willing to step up, we’ll figure it out,” Subrahmanian said, “because there is such a need.”

Martha Bebinger is a WBUR reporter

This article is from a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR, and KFF Health News.

Martha Bebinger, WBUR: marthab@wbur.org, @mbebinger

Where I became an American

In Faneuil Hall

“I became an American on Nov. 4, 2010, at an elegant ceremony in the Great Hall of Bullfinch's Faneuil Hall, Boston, beneath a vast painting of Sen. Daniel Webster debating the preservation of the Union with Robert Hayne of South Carolina {in 1830}.’’

— Nigel Hamilton (born 1944), British-born historian

The Massachusetts senator’s speech is considered by many to be the greatest in U.S. Senate history.

New age of sail

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I mention this in part because New England has such a sailing tradition.

There’s a small but growing move to bring back sail for cargo ships, to reduce fuel costs and the ocean shipping’s sector’s carbon footprint. This could become a big deal over the next decade. A total of more than 100,000 ships transport more than 80 percent of products in world trade.

Tech advances are making mostly wind-powered vessels more economically attractive these days. They’re supplemented by engines to navigate in very narrow waters and when the wind fails. Note the mechanized systems for raising and adjusting sails, giant carbon-fiber masts, light aluminum hulls, highly computerized navigation systems and steadily improving wind forecasting. At the same time, giant rigid sails are being installed on what had been totally engine-powered vessels as power supplements.

Clarksons Research says a total of 165 cargo ships are either already using some wind power or will have wind systems installed. Maritime painters loved making pictures of clipper and other big sailing vessels. Now they have new dramatic images to play with.

When all seemed possible

“Piggy-Back” (acrylic paint, enamel paint, paper on canvas), by Bob Dilworth, in his show “When I Remembered Home,’’ at the Fitchburg (Mass.) Art Museum through Jan. 12

—Courtesy of the artist and Cade Tompkins Projects

Llewellyn King: A ‘missing link’ for renewable-energy generation

— Photo by Herbert Glarner

In a well-ordered laboratory in Owings Mills, a suburb of Baltimore, an engineer has been perfecting a device that might be called the missing link in renewable energy.

Now it is ready to begin its transformative role in electric generation. And to bring electricity to the remotest places in America, as well as adding it to the grid.

It is an invention that could cut the cost of new wind turbines, make solar more desirable and turn tens of thousands – yes, thousands — of U.S. streams and non-powered dams into power generators without huge civil engineering outlays.

The company is DDMotion, and its creative force is Key Han, president and chief scientist. Han has spent more than a decade perfecting his patented invention which takes variable inputs and converts them to a constant output.

In a stream, this consists of taking the variables in the water flow and turning them into a constant, reliable shaft output that can generate constant frequency ready to be fed to the grid. Likewise with wind and solar.

Han told me the environmental impact on a stream or river would be negligible, essentially undetected, but a reliable amount of grid-grade electricity could be obtained at all times in all kinds of weather.

He has dreams of a world where every bit of flowing water could be a resource for many power plants, and the same technologies would be essential in harnessing the energy of ocean currents.

A further advantage to Han’s constant-speed device is that with a rotating shaft, it is a source of what in the more arcane reaches of the electrical world is known as rotational inertia. Arcane but essential.

This is the slowing down of something that was once moving briskly, like stopping a car. In power generation, this can be a few seconds, but it is necessary to enable an electrical system to keep its output constant — 60 cycles per second in America, 50 cycles per second in Europe and parts of Asia. If that varies, the whole system fails. Blackout. Then the system must be recalibrated, and that can take days or several weeks for the whole grid.

Electricity needs rotational inertia. With fossil-fueled plants, this isn’t a problem: There is always rotational inertia in their rotating parts.

Wind power loses its inertia, which is there initially as the wind turns a shaft, but is lost as the power generated is groomed for the grid. It passes through a gearbox then to an inverter, which converts the power from direct current to grid-compatible alternating current.

Han says using his technology, the gearbox and the inverter can be eliminated and inertia provided. Also, most of the remaining hardware could be located on the ground rather than up in the air on the tower, making for less installation cost and easier maintenance.

Loss of inertia is becoming a problem for grids in Europe, where wind and solar are approaching half of the generating load. Germany, particularly, must create ancillary services.

Han told me, “DDmotion-developed speed converters can harness all renewable energy with benefits. For example, wind turbines can produce rotating inertia, therefore ancillary services are not required to keep the grid frequency stable, and river turbines without dams can generate baseload, therefore storage systems, such as batteries and pump storage are not required.”

DDMotion has been largely supported by Alfred Berkeley, chairman of Princeton Capital Management and a legend in the financial community. He served as president of Nasdaq and later as its vice chairman.

Han, who holds many patents relating to his work on infinitely variable motion controls, began his career at General Electric before founding DDMotion in 1990.

A native of South Korea, Han attended college in Montana so that he could fulfill his dream of becoming a professional cowboy. His resume includes roping and branding calves one summer.

If DDMotion succeeds as Han and his supporters hope, their missing link will vastly enhance the value of renewable energy and bring down its cost to the system and to consumers.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com.

Elements of us all

“Geomania’’ (still), (1987) (two-channel video matrix installation, color, sound, 15 minutes), by Vasulka Steina, at the MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, Mass., through Jan. 12.

— Courtesy the artist and Berg Contemporary