Longing for Indian summer

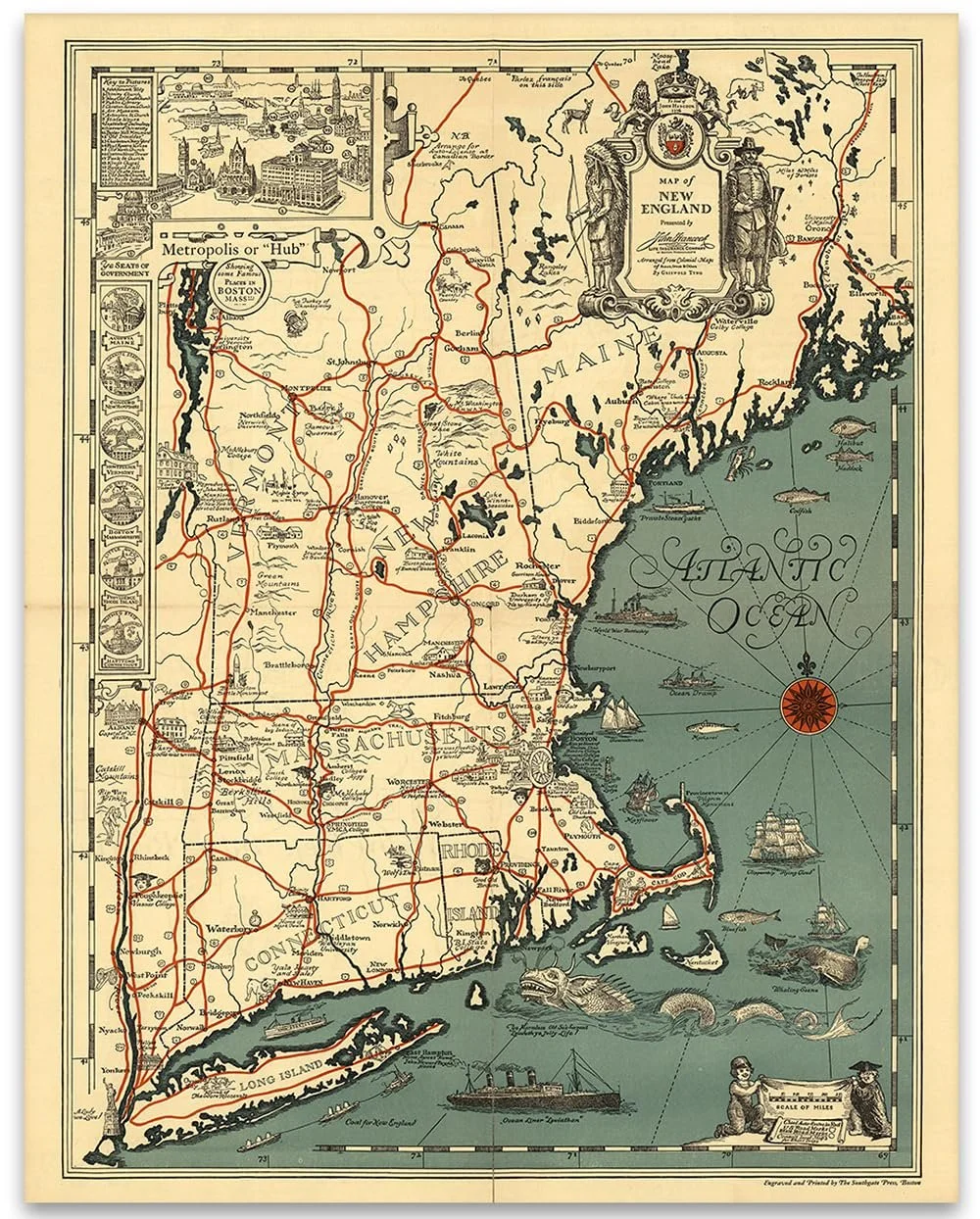

In the Berkshires

“Those grown old, who have had the youth bled from them by the jagged edged winds of winter, know sorrowfully that Indian summer is a sham to be met with hard-eyed cynicism. But the young wait anxiously, scanning the chill autumn skies for a sign of her coming.’’

— From Grace Metalious’s 1956 novel Peyton Place, set in a small New Hampshire town and considered by many at the time to be pornographic. It looks very tame now.

It's not all that bad

A flower, a skull, and an hourglass stand for life, death and time in this 17th-Century painting by Philippe de Champaigne.

To him who in the love of Nature holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language; for his gayer hours

She has a voice of gladness, and a smile

And eloquence of beauty, and she glides

Into his darker musings, with a mild

And healing sympathy, that steals away

Their sharpness, ere he is aware. When thoughts

Of the last bitter hour come like a blight

Over thy spirit, and sad images

Of the stern agony, and shroud, and pall,

And breathless darkness, and the narrow house,

Make thee to shudder, and grow sick at heart;—

Go forth, under the open sky, and list

To Nature’s teachings, while from all around

Earth and her waters, and the depths of air—

Comes a still voice—Yet a few days, and thee

The all-beholding sun shall see no more

In all his course; nor yet in the cold ground,

Where thy pale form was laid, with many tears,

Nor in the embrace of ocean, shall exist

Thy image. Earth, that nourished thee, shall claim

Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again,

And, lost each human trace, surrendering up

Thine individual being, shalt thou go

To mix for ever with the elements,

To be a brother to the insensible rock

And to the sluggish clod, which the rude swain

Turns with his share, and treads upon. The oak

Shall send his roots abroad, and pierce thy mould.

Yet not to thine eternal resting-place

Shalt thou retire alone, nor couldst thou wish

Couch more magnificent. Thou shalt lie down

With patriarchs of the infant world—with kings,

The powerful of the earth—the wise, the good,

Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past,

All in one mighty sepulchre. The hills

Rock-ribbed and ancient as the sun,—the vales

Stretching in pensive quietness between;

The venerable woods—rivers that move

In majesty, and the complaining brooks

That make the meadows green; and, poured round all,

Old Ocean’s gray and melancholy waste,—

Are but the solemn decorations all

Of the great tomb of man. The golden sun,

The planets, all the infinite host of heaven,

Are shining on the sad abodes of death,

Through the still lapse of ages. All that tread

The globe are but a handful to the tribes

That slumber in its bosom.—Take the wings

Of morning, pierce the Barcan wilderness,

Or lose thyself in the continuous woods

Where rolls the Oregon, and hears no sound,

Save his own dashings—yet the dead are there:

And millions in those solitudes, since first

The flight of years began, have laid them down

In their last sleep—the dead reign there alone.

So shalt thou rest, and what if thou withdraw

In silence from the living, and no friend

Take note of thy departure? All that breathe

Will share thy destiny. The gay will laugh

When thou art gone, the solemn brood of care

Plod on, and each one as before will chase

His favorite phantom; yet all these shall leave

Their mirth and their employments, and shall come

And make their bed with thee. As the long train

Of ages glide away, the sons of men,

The youth in life’s green spring, and he who goes

In the full strength of years, matron and maid,

The speechless babe, and the gray-headed man—

Shall one by one be gathered to thy side,

By those, who in their turn shall follow them.

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave,

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

— “Thanatopsis,’’ by William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878), American romantic poet and famed New York-based editor. He grew up in western Massachusetts.

Transit textures

“Carscape #3,’’ by Maine painter Winslow Myers, in his show “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, opening Oct. 30.

The gallery says:

“In his first Boston show, modes of transport provide opportunities for the artist to play abstractly with form, space, color and light.’’

Above Logan International Airport, on Boston Harbor.

Chris Powell: Promote Connecticut’s gentle beauty and fix its government

Connecticut River as seen from Gillette Castle, in East Haddam, Conn.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

One of these days Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont may show Florida a thing or two. But probably not soon.

Without explanation, Florida's tourism Internet site recently removed a section touting destinations in the state said to be particularly attractive to members of sexual minorities. This renewed complaints that the state is hostile to those minorities because of its "Don't Say Gay" law, its refusal to let people change the sex listed on their driver's licenses, its prohibition of sex-change therapy for minors, and its requiring people to use restrooms corresponding to their biological sex.

As oppression goes, this isn't much. The "Don't Say Gay" law only forbids school class discussions of homosexuality in third grade and below, in the reasonable belief that any sex-related discussions aren't appropriate for younger children.

The prohibition on changing sex designations on driver's licenses guards against deception.

The prohibition on sex-change therapy for minors protects them against irreversible, life-changing treatment until they are fully able to make their own decisions. (All states prohibit certain things for minors, including Connecticut.)

Members of sexual minorities who live in Florida may disagree with these policies but apparently not enough to leave the state. Florida long has been and remains attractive to them, and their share of the population in Florida seems to equal or exceed their share of the country's population. An independent internet site on Florida tourism lists dozens of localities considered "gay-friendly," many with "gayborhoods," along with dozens of attractions that might appeal particularly to them.

And supposedly backward Florida has been gaining population while supposedly progressive Connecticut has been losing it.

So having already appealed to Florida businesses to relocate to Connecticut because of Florida's restrictive abortion law -- a law that probably will be liberalized by voters in a referendum in November -- Governor Lamont this month had Connecticut's tourism office undertake an internet advertising campaign aimed at sexual minorities, emphasizing the state as "a welcoming alternative."

Of course this campaign won't be any more effective than was the governor's appeal to Florida businesses to relocate to Connecticut because of abortion law. Both undertakings are just politically correct posturing by the governor, a Democrat who has been finding it harder to maintain the support of his party's extreme left. His posturing won't do much to keep the lefties in line either.

If only the governor could plausibly issue an appeal to Floridians, including the many who used to live in Connecticut (among them former Gov. Jodi Rell), that they should return here because of, say, the stunning new efficiency of state and municipal government, much-improved public education, reduction in taxes, and a rising standard of living.

After all, Florida's weather isn't that state's only attraction; it's not even all that good. Florida's winter can be lovely while Connecticut shivers, shovels, slips, and crashes. But Florida's summer can be oppressively hot, rain there can go on for days and is often torrential, hurricanes are frequent and can be catastrophic, and the state is full of mosquitoes, alligators, Burmese pythons, and cranky old people driving haphazardly to and from their doctor's office.

Florida's lack of a state income tax may be a bigger draw than its weather. While tax revenue from the state's tourism industry takes much financial pressure off state government, so does Florida's refusal to be taken over by the government class, a big difference from Connecticut. Florida's strengthening Republican Party may help in that respect, even as Connecticut's Republican Party and political competition in the state have nearly disappeared.

Connecticut's natural advantages remain what they always have been. Beautiful hills, valleys, meadows, forests, rivers, streams, lakes, a long seashore, changeable but generally moderate weather, and nearness to but comfortable distance from two metropolitan areas. It is a great but gentle beauty, crowned with convenience.

That is, Connecticut is a state to be lived in, not visited. Indeed, contrary to the governor's latest pose, the fewer tourists here, the better. Connecticut would be more wonderful still if government didn't keep making it more expensive, thus making Florida seem better.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Aid to navigation

From the series “Another America,’’ by Philip Toledano. He’s in the group show “Artificial Intelligence: DisInformation in a Post Truth World,’’ at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Winchester, Mass. through Oct. 27.

Train at the Winchester MBTA station in October 2008, between the Town Hall and the First Congregational Church. Winchester is an affluent inner suburb of Boston.

The museum says the show focuses on how images inform, persuade and drive the conversation about critical thinking.

Northeastern University breaks ground on Portland campus

-- Northeastern University's rendition of what its Roux Institute campus on the Portland waterfront will look like.

Edited from a New England Council report

“On Friday, Sept. 13, New England Council member Northeastern University held a groundbreaking ceremony to mark construction on its new campus in Portland, Maine, that will let the university to double the student body at the location.

“The Roux Institute at Northeastern University’s new campus will mark a significant step forward for Northeastern. The institute opened in 2020, thanks to a $100 million donation from technology entrepreneur David Roux, a Maine native, as well as another $100 million gift months later. The school has 800 students today, but it expects to have room for 2,000 when the new campus is completed, in 2028. The Roux is focused on technology research and development and graduate education.

“‘Our mission is to be a driver of the future Maine economy…. A larger permanent home for the university’s efforts in Maine is essential,’ the Roux Institute’s chief administrative officer, Chris Mallett, said in an interview.’’

Maniacal in Maine

Installation view of “Alive & Kicking: Fantastic Installations by Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, Catalina Schliebener Muñoz, and Gladys Nilsson,’’ at the Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, through Nov. 11.

—Photography by Andrew Witte

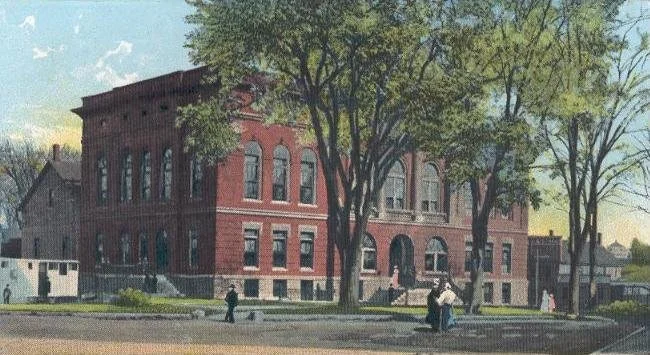

City Hall and Opera House in 1905 in Waterville, where appreciation for the arts goes way back.

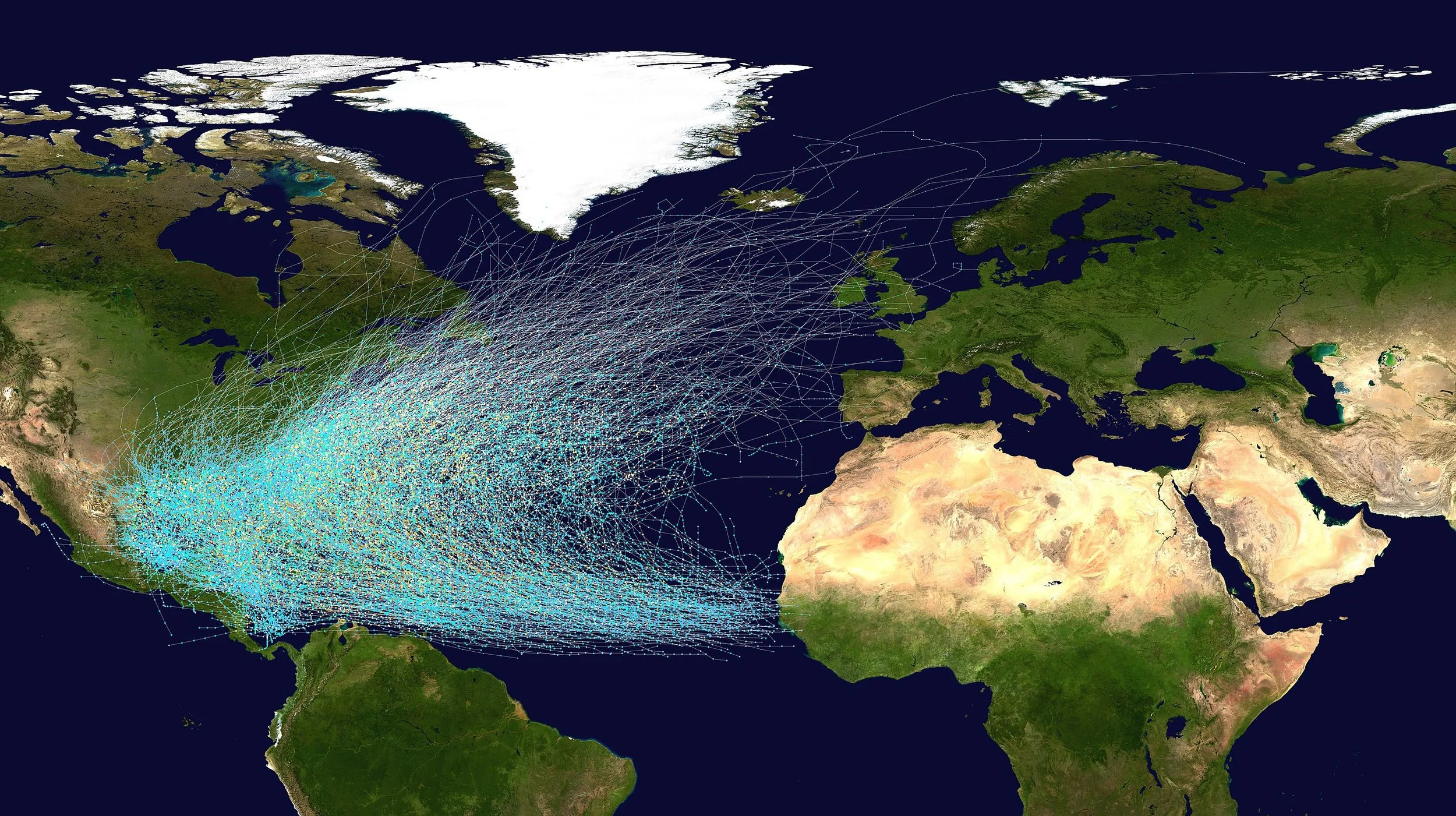

James L. Fitzsimmons: Of hurricanes and Huracan

Tracks of North Atlantic tropical cyclones 1851-2019

MIDDLEBURY, Vt.

The ancient Maya believed that everything in the universe, from the natural world to everyday experiences, was part of a single, powerful spiritual force. They were not polytheists who worshipped distinct gods but pantheists who believed that various gods were just manifestations of that force.

Some of the best evidence for this comes from the behavior of two of the most powerful beings of the Maya world: The first is a creator god whose name is still spoken by millions of people every fall – Huracán, or “Hurricane.” The second is a god of lightning, K'awiil, from the early first millennium C.E.

As a scholar of the Indigenous religions of the Americas, I recognize that these beings, though separated by over 1,000 years, are related and can teach us something about our relationship to the natural world.

Huracán, the ‘Heart of Sky’

Huracán was once a god of the K’iche’, one of the Maya peoples who today live in the southern highlands of Guatemala. He was one of the main characters of the Popol Vuh, a religious text from the 16th century. His name probably originated in the Caribbean, where other cultures used it to describe the destructive power of storms.

The K’iche’ associated Huracán, which means “one leg” in the K’iche’ language, with weather. He was also their primary god of creation and was responsible for all life on earth, including humans.

Because of this, he was sometimes known as U K'ux K'aj, or “Heart of Sky.” In the K'iche’ language, k'ux was not only the heart but also the spark of life, the source of all thought and imagination.

Yet, Huracán was not perfect. He made mistakes and occasionally destroyed his creations. He was also a jealous god who damaged humans so they would not be his equal. In one such episode, he is believed to have clouded their vision, thus preventing them from being able to see the universe as he saw it.

Huracán was one being who existed as three distinct persons: Thunderbolt Huracán, Youngest Thunderbolt and Sudden Thunderbolt. Each of them embodied different types of lightning, ranging from enormous bolts to small or sudden flashes of light.

Despite the fact that he was a god of lightning, there were no strict boundaries between his powers and the powers of other gods. Any of them might wield lightning, or create humanity, or destroy the Earth.

Another storm god

The Popol Vuh implies that gods could mix and match their powers at will, but other religious texts are more explicit. One thousand years before the Popol Vuh was written, there was a different version of Huracán called K'awiil. During the first millennium, people from southern Mexico to western Honduras venerated him as a god of agriculture, lightning and royalty.

The ancient Maya god K'awiil, left, had an ax or torch in his forehead as well as a snake in place of his right leg. K5164 from the Justin Kerr Maya archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C., CC BY-SA

Illustrations of K'awiil can be found everywhere on Maya pottery and sculpture. He is almost human in many depictions: He has two arms, two legs and a head. But his forehead is the spark of life – and so it usually has something that produces sparks sticking out of it, such as a flint ax or a flaming torch. And one of his legs does not end in a foot. In its place is a snake with an open mouth, from which another being often emerges.

Indeed, rulers, and even gods, once performed ceremonies to K'awiil in order to try and summon other supernatural beings. As personified lightning, he was believed to create portals to other worlds, through which ancestors and gods might travel.

Representation of power

For the ancient Maya, lightning was raw power. It was basic to all creation and destruction. Because of this, the ancient Maya carved and painted many images of K'awiil. Scribes wrote about him as a kind of energy – as a god with “many faces,” or even as part of a triad similar to Huracán.

He was everywhere in ancient Maya art. But he was also never the focus. As raw power, he was used by others to achieve their ends.

Rain gods, for example, wielded him like an ax, creating sparks in seeds for agriculture. Conjurers summoned him, but mostly because they believed he could help them communicate with other creatures from other worlds. Rulers even carried scepters fashioned in his image during dances and processions.

Moreover, Maya artists always had K'awiil doing something or being used to make something happen. They believed that power was something you did, not something you had. Like a bolt of lightning, power was always shifting, always in motion.

An interdependent world

Because of this, the ancient Maya thought that reality was not static but ever-changing. There were no strict boundaries between space and time, the forces of nature or the animate and inanimate worlds.

Residents wade through a street flooded by Hurricane Helene, in Batabano, Mayabeque province, Cuba, on Sept. 26, 2024. AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa

Everything was malleable and interdependent. Theoretically, anything could become anything else – and everything was potentially a living being. Rulers could ritually turn themselves into gods. Sculptures could be hacked to death. Even natural features such as mountains were believed to be alive.

These ideas – common in pantheist societies – persist today in some communities in the Americas.

They were once mainstream, however, and were a part of K'iche’ religion 1,000 years later, in the time of Huracán. One of the lessons of the Popol Vuh, told during the episode where Huracán clouds human vision, is that the human perception of reality is an illusion.

The illusion is not that different things exist. Rather it is that they exist independent from one another. Huracán, in this sense, damaged himself by damaging his creations.

Hurricane season every year should remind us that human beings are not independent from nature but part of it. And like Hurácan, when we damage nature we damage ourselves.

James L. Fitzsimmons is a professor of anthropology at Middlebury College.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

‘For the grapes’ sake’

Fall foliage in New Hampshire. (Photo by --bluepoint - Flickr)

O hushed October morning mild,

Thy leaves have ripened to the fall;

Tomorrow’s wind, if it be wild,

Should waste them all.

The crows above the forest call;

Tomorrow they may form and go.

O hushed October morning mild,

Begin the hours of this day slow.

Make the day seem to us less brief.

Hearts not averse to being beguiled,

Beguile us in the way you know.

Release one leaf at break of day;

At noon release another leaf;

One from our trees, one far away.

Retard the sun with gentle mist;

Enchant the land with amethyst.

Slow, slow!

For the grapes’ sake, if they were all,

Whose leaves already are burnt with frost,

Whose clustered fruit must else be lost—

For the grapes’ sake along the wall.

— “October,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Wild grapes in the fall. (Photo by Sten Porse)

The way we live now

“Absenthood” (digital image), by Dominique Gustin, at AVA Gallery and Art Center, Lebanon, N.H.

A coast for artists

"Taking a Day Off'' (acrylic), by Del-Bourree Bach, in the group show "Maine Stories,'' at Sarah Powell Fine Art, Madison, Conn.

Along a dangerously exposed stretch of expensive houses in Madison, Conn., on Long Island Sound. (Photo by Léo Schmitt)

The gallery says that the show “celebrates a landscape tradition which has captivated generations of artists for over 100 years, from Thomas Cole and Frederick Church to Winslow Homer and Andrew Wyeth. A vital place of artistic inspiration, Maine’s rugged coastline, churning seas, iconic lighthouses, vivid buoys, lobster boats and historic harbors have been subjects for some of America’s finest painters.’’

Ceating a reservoir and a wilderness

Looking north up the Swift River Valley from Quabbin Hill, in central Masssachusetts, on Aug. 14, 1939, shortly before a dam started to create the huge lake that was to be the major water supply for Greater Boston.

“In front of me stretched the water of the Quabbin {Reservoir}. It was for this water that the Swift River Valley was flooded. It was because of this water that the wilderness, with its eagles and its extensive woodlands and abandoned cellar holes, exist in the Quabbin region.’’

— From Quabbin, The Accidental Wilderness (1981), by Thomas Conuel

The Quabbin Reservoir in November 2005.

Risking it all

From Robert Whitcomb “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Eileen Warburton’s new book, Chasing Chance: Stories of the Peirce-Prince Families in America, is riveting American history structured through the interwoven narratives of two families who arrived in New England from England in “The Great Migration’’ of Puritans to New England, 1620-1640.

“Chance” in this context means accepting risk.

This is not some dry genealogical tome. Rather, this brilliantly researched, written and illustrated work narrates the sagas of memorable characters, many heroic, some not, in ways that can suggest life lessons for everyone. What to do, what not to do.

The cast of characters include austere and deeply religious Puritans, alleged witches, sea captains, Confederate officers, business moguls, scholars, artists, statesmen, war heroes and founders of towns, states, and companies. They’re never shown as stock figures but as idiosyncratic people in the round, with anger, occasional ruthlessness and other problematic elements mixed in with such admirable qualities as courage in the face of high, even lethal risks, ingenuity, generosity, civic leadership and plenty of romance.

‘Sci-Fi Sufism’

"Praying A.N.G.E.L.S." (foam print), by Saks Afridi, in his show ""SpaceMosque,'' at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum & Art Center, through Oct. 19.

He explains:

“My work exists in a genre I term as ‘Sci-Fi Sufism’, which is about discovering galaxies and worlds within yourself. I try to visualize this search by fusing mysticism and storytelling. I make art objects in multiple mediums and I draw inspiration from Sufi poetry, South Asian folklore, Islamic mythology, science fiction, architecture and calligraphy.’’

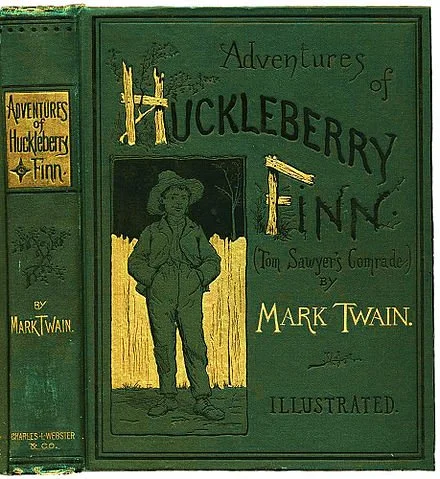

Chris Powell: The misnamed 'Banned Books Week'; about that bus highway

Mark Twain's famed novel has been banned in some American schools because of its racial language.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Last week was what librarians and leftists in Connecticut and throughout the country call Banned Books Week. A more accurate name for it would be Submit to Authority Week.

The week is misnamed because in the United States there are no banned books at all -- no books whose publication and possession are forbidden by government. Banned Books Week has been contrived by librarians and leftists to intimidate people out of criticizing certain books that librarians and school administrators have chosen for inclusion in school libraries, curriculums, and public libraries. The objective is to prevent libraries and schools from ever having to answer to anyone for their choices.

The selection of every book for a library or curriculum is always a matter of judgment. But the promoters of Banned Books Week would have the public believe that the choices made by librarians and school administrators are always right, and that anyone who questions these choices is a follower of Hitler or, worse, Donald Trump.

Some criticism of library and curriculum choices is nutty. Two great works of American literature that have helped to defeat racism -- Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird -- are sometimes targeted by people who can't get past the occasional racist language in them.

But these days most books whose inclusion in schools and libraries are challenged involve homosexuality and transgenderism, and these are fairly challenged at least in regard to their appropriateness for children, especially amid the mental illness that is worsening among them.

This doesn't mean that such books should be excluded automatically but that their appropriateness should be settled by thoughtful review and discussion. Calling a book's critics "book banners" and a book's advocates "groomers," as is common in these controversies, is not thoughtful.

The great irony of Banned Books Week is that as a practical matter its promoters are themselves the biggest book banners. That is, with a virtually infinite number of books in the world, librarians and school administrators reject thousands of books for every one they include.

Of course not all books can be included in any library or curriculum. Do the choices that are made give a politically balanced view of the world and academic subjects or a politically skewed and propagandist one?

If Banned Books Week succeeds, no one will ever know -- which is the idea.

Shelter along the CTfastrak route

The once-controversial bus highway between Hartford and New Britain, CTfastrak, has been operating for 10 years, and this week Connecticut's Hearst newspapers sought to determine if, after a construction cost of more than half a billion dollars, the busway can be considered a success.

CTfastrak has turned 10 and seen an increase in riders from a pandemic dip

CTfastrak has turned 10 and seen an increase in riders from a pandemic dip

CTfastrak has turned 10 and seen an increase in riders from a pandemic dip

CTfastrak has turned 10 and seen an increase in riders from a pandemic dip

The state Transportation Department says the highway had 2.8 million riders in 2016, its first full year of operation, reached a peak of 3.3 million riders in 2019, and then, amid the Covid-19 epidemic, fell to about 2 million riders in 2021 and has been slowly increasing since.

But the chief of the department's Bureau of Public Transit, Ben Limmer, was unable to provide information crucial to a judgment on the project. While it stands to reason that the bus highway has reduced automobile commuting between Hartford and New Britain, the department says it has no data on that. More concerning is that the department can't or won’t say how much each CTfastrak rider is being subsidized by state government.

"We do what we can to make sure fares are affordable," Limmer said. "I assume fares have not kept up with inflation, so we’re probably flat or slightly up on subsidies."

All modes of transportation -- sidewalks, streets and highways, trains, and airplanes -- are subsidized by government in some way. But now that the epidemic-induced trend of working from home has greatly reduced commuting, CTfastrak is even more questionable than it was when it began.

Does the Transportation Department want to know what CTfastrak’s operating costs are and how much riders are being subsidized? It doesn't seem to want the public to know.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Trying to recognize absence

At Rhonda Smith’s show, “Undiscovered Country,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Oct. 29-Dec. 1. She is based in Boston and Biddeford Pool, Maine.

The gallery says “‘Undiscovered Country’ derives from various influences: sea tales, myths, poems, industrial and natural elements, medieval imagery, photographs, and contemporary statistics. These influences emerge during the creation of each piece. Rhonda Smith relies on the tactile process of shaping, molding, and assembling materials to give form to her ideas. Initial concepts often remain skeletal or merely impulsive, while the true essence of a piece develops through the tactile process of listening to what her hands transmute.

”The sculptures and installations, with their broad mix of materials and techniques, represent both disappearance and appearance—experiences that are simultaneously deeply satisfying and fragile; Will humans disappear and nature survive? Is our possibility now in recognizing absence? Smith remains increasingly aware that, in the face of crumbling realities, only her openness to the undiscovered will have significance. For Smith, this is what art can achieve: guiding us towards new ground.’’

Llewellyn King: Trove of latters takes us inside the Civil War

Some American Civil War related pictures via Wikipedia

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Just when you thought that every word that could be written about the American Civil War had been written, every book published, along comes an exciting collection of new information.

Such a happening comes as a new book — still seeking a publisher — from Civil War aficionado J. Mark Powell, the editor at InsideSources, a syndication service.

Before electronic recording devices, letters were the eyewitnesses to history. The discovery of a trove of these is a light beamed into the past.

Powell’s book is a compilation he has made in 20 years of seeking, collecting, chasing down, and sometimes buying unpublished letters from the war. He has collated these and provided just enough annotation to make them an easy and engrossing read.

In all there are nearly 500 letters from every social strata affected by the tumult — from a slave to many tender notes between families torn apart and sometimes divided between North and South. It is history in the raw, modified only by Powell’s scholarship and loving curation.

The letters were written between husbands and wives, between lovers, between parents and children, and between brothers. They provide untrammeled truth or truth reflected by the station of the writers.

It is truth that hasn’t been adulterated for political purposes, then or now, as often happens, with the weaponizing of history.

These letters take the reader into the war, its hope and its horror. It is life as it was lived by ordinary people, soldier and wife, mother and child between 1861 and 1865, through the eyes of people who lived the war, and sometimes died.

Powell told me, “This is the first account of its kind, to the best of my knowledge. It is just a completely unique approach.

“This isn’t a textbook recitation of names and dates and places. I tried to capture how it felt to live through those terrible times. The pride, the hopes, the fears, the uncertainty, and even the humor is all in this collation of the letters for those who endured the war on both sides.”

There are no famous names here, no excerpts from famous generals or major historical figures. Rather, these are the everyday people who lived through the war and, in some cases, didn’t survive.

Powell is a seasoned journalist who worked for several local TV stations, CNN, and on Capitol Hill before alighting at InsideSources. He is also the author of a novel and has collaborated on another. He has given much of his life to studying the Civil War — a fascination which began as a 10-year-old.

Powell said his work is also a cautionary tale for 2024, “because the war resulted from two sides that had dug in their heels and refused to budge. Very much the same way America is suffering the hardening of the political arteries right now.”

In one letter from his book, a woman named Genevieve Byrne Runyon lost her husband, James, an officer in the 26th Iowa Infantry in 1862. He had been dead for nearly three years when his regiment returned home.

This is her anguish as she related it to her late husband’s brother in a letter dated Dewitt, Iowa, August 18, 1865:

“I suppose you would like to know how I am getting along. I had my father move into my house and I am keeping house for him. Yet I feel like a wanderer looking for someone that I’ll never see again. It feels foolish to be ever complaining, but I cannot help it. I could write forever on the subject.

“How I felt when the remainder of his regiment returned without him, I cannot describe. I felt I had lost him forever on this earth. Now that the cruel war is over and I look back and see the many lonely homes, I wonder what it all meant.”

Powell, who writes the weekly syndicated, historical column “Holy Cow,” told me, “I’ve had that letter for over 20 years now, and that last line still haunts me every time I read it.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

White House Chronicle

Amy Waxman: Nurses’ aides say they’re plagued by PTSD from work during COVID at Mass. facility

The Massachusetts Veterans Home in Holyoke.

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (KFF)

One evening in May, nursing assistant Debra Ragoonanan’s vision blurred during her shift at a state-run Massachusetts veterans home. As her head spun, she said, she called her husband. He picked her up and drove her to the emergency room, where she was diagnosed with a brain aneurysm.

It was the latest in a drumbeat of health issues that she traces to the first months of 2020, when dozens of veterans died at the Soldiers’ Home in Holyoke, in one of the country’s deadliest COVID-19 outbreaks at a long-term nursing facility. Ragoonanan has worked at the home for nearly 30 years. Now, she said, the sights, sounds, and smells there trigger her trauma. Among her ailments, she lists panic attacks, brain fog, and other symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition linked to aneurysms and strokes.

Scrutiny of the outbreak prompted the state to change the facility’s name to the Massachusetts Veterans Home at Holyoke, replace its leadership, sponsor a $480 million renovation of the premises, and agree to a $56 million settlement for veterans and families. But the front-line caregivers have received little relief as they grapple with the outbreak’s toll.

“I am retraumatized all the time,” Ragoonanan said, sitting on her back porch before her evening shift. “How am I supposed to move forward?”

Covid killed more than 3,600 U.S. health-care workers in the first year of the pandemic. It left many more with physical and mental illnesses — and a gutting sense of abandonment.

What workers experienced has been detailed in state investigations, surveys of nurses, and published studies. These found that many health-care workers weren’t given masks in 2020. Many got COVID and worked while sick. More than a dozen lawsuits filed on behalf of residents or workers at nursing facilities detail such experiences. And others allege that accommodations weren’t made for workers facing depression and PTSD triggered by their pandemic duties. Some of the lawsuits have been dismissed, and others are pending.

Health-care workers and unions reported risky conditions to state and federal agencies. But the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration had fewer inspectors in 2020 to investigate complaints than at any point in a half-century. It investigated only about 1 in 5 covid-related complaints that were filed officially, and just 4 percent of more than 16,000 informal reports made by phone or email.

Nursing assistants, health aides, and other lower-wage health-care workers were particularly vulnerable during outbreaks, and many remain burdened now. About 80 percent of lower-wage workers who provide long-term care are women, and these workers are more likely to be immigrants, to be people of color, and to live in poverty than doctors or nurses.

Some of these factors increased a person’s COVID risk. They also help explain why these workers had limited power to avoid or protest hazardous conditions, said Eric Frumin, formerly the safety and health director for the Strategic Organizing Center, a coalition of labor unions.

He also cited decreasing membership in unions, which negotiate for higher wages and safer workplaces. One-third of the U.S. labor force was unionized in the 1950s, but the level has fallen to 10 percent in recent years.

Like essential workers in meatpacking plants and warehouses, nursing assistants were at risk because of their status, Frumin said: “The powerlessness of workers in this country condemns them to be treated as disposable.”

In interviews, essential workers in various industries told KFF Health News they felt duped by a system that asked them to risk their lives in the nation’s moment of need but that now offers little assistance for harm incurred in the line of duty.

“The state doesn’t care. The justice system doesn’t care. Nobody cares,” Ragoonanan said. “All of us have to go right back to work where this started, so that’s a double whammy.”

‘A War Zone’

The plight of health-care workers is a problem for the United States as the population ages and the threat of future pandemics looms. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy called their burnout “an urgent public health issue” leading to diminished care for patients. That’s on top of a predicted shortage of more than 3.2 million lower-wage health care workers by 2026, according to the Mercer consulting firm.

The veterans home in Holyoke illustrates how labor conditions can jeopardize the health of employees. The facility is not unique, but its situation has been vividly described in a state investigative report and in a report from a joint oversight committee of the Massachusetts Legislature.

The Soldiers’ Home made headlines in March 2020 when The Boston Globe got a tip about refrigerator trucks packed with the bodies of dead veterans outside the facility. About 80 residents died within a few months.

The state-run Soldiers’ Home in Holyoke, Massachusetts, was the scene of one of the country’s deadliest covid outbreaks at a long-term nursing facility. Scrutiny of the outbreak prompted the state to change the home’s name, replace its leadership, and agree to a $56 million settlement for veterans and their families. But front-line caregivers have received little relief as they continue to grapple with the trauma.(Amy Maxmen/KFF Health News)

The state investigation placed blame on the home’s leadership, starting with Superintendent Bennett Walsh. “Mr. Walsh and his team created close to an optimal environment for the spread of COVID-19,” the report said. He resigned under pressure at the end of 2020.

Investigators said that “at least 80 staff members” tested positive for covid, citing “at least in part” the management’s “failure to provide and require the use of proper protective equipment,” even restricting the use of masks. They included a disciplinary letter sent to one nursing assistant who had donned a mask as he cared for a sick veteran overnight in March. “Your actions are disruptive, extremely inappropriate,” it said.

To avoid hiring more caretakers, the home’s leadership combined infected and uninfected veterans in the same unit, fueling the spread of the virus, the report found. It said veterans didn’t receive sufficient hydration or pain-relief drugs as they approached death, and it included testimonies from employees who described the situation as “total pandemonium,” “a nightmare,” and “a war zone.”

Because his wife was immunocompromised, Walsh didn’t enter the care units during this period, according to his lawyer’s statement in a deposition obtained by KFF Health News. “He never observed the merged unit,” it said.

In contrast, nursing assistants told KFF Health News that they worked overtime, even with COVID because they were afraid of being fired if they stayed home. “I kept telling my supervisor, ‘I am very, very sick,’” said Sophia Darkowaa, a nursing assistant who said she now suffers from PTSD and symptoms of long COVID. “I had like four people die in my arms while I was sick.”

Nursing assistants recounted how overwhelmed and devasted they felt by the pace of death among veterans whom they had known for years — years of helping them dress, shave, and shower, and of listening to their memories of war.

“They were in pain. They were hollering. They were calling on God for help,” Ragoonanan said. “They were vomiting, their teeth showing. They’re pooping on themselves, pooping on your shoes.”

Nursing assistant Kwesi Ablordeppey said the veterans were like family to him. “One night I put five of them in body bags,” he said. “That will never leave my mind.”

Four years have passed, but he said he still has trouble sleeping and sometimes cries in his bedroom after work. “I wipe the tears away so that my kids don’t know.”

High Demands, Low Autonomy

A third of health-care workers reported symptoms of PTSD related to the pandemic, according to surveys between January 2020 and May 2022 covering 24,000 workers worldwide. The disorder predisposes people to dementia and Alzheimer’s. It can lead to substance use and self-harm.

Since COVID began, Laura van Dernoot Lipsky, director of the Trauma Stewardship Institute, has been inundated by emails from health care workers considering suicide. “More than I have ever received in my career,” she said. Their cries for help have not diminished, she said, because trauma often creeps up long after the acute emergency has quieted.

Another factor contributing to these workers’ trauma is “moral injury,” a term first applied to soldiers who experienced intense guilt after carrying out orders that betrayed their values. It became common among health care workers in the pandemic who weren’t given ample resources to provide care.

“Folks who don’t make as much money in health care deal with high job demands and low autonomy at work, both of which make their positions even more stressful,” said Rachel Hoopsick, a public-health researcher at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “They also have fewer resources to cope with that stress,” she added.

People in lower-income brackets have less access to mental-health treatment. And health-care workers with less education and financial security are less able to take extended time off, to relocate for jobs elsewhere, or to shift careers to avoid retriggering their traumas.

Such memories can feel as intense as the original event. “If there’s not a change in circumstances, it can be really, really, really hard for the brain and nervous system to recalibrate,” van Dernoot Lipsky said. Rather than focusing on self-care alone, she pushes for policies to ensure adequate staffing at health facilities and accommodations for mental health issues.

In 2021, Massachusetts legislators acknowledged the plight of the Soldiers’ Home residents and staff in a joint committee report saying the events would “impact their well-being for many years.”

But only veterans have received compensation. “Their sacrifices for our freedom should never be forgotten or taken for granted,” the state’s veterans services director, Jon Santiago, said at an event announcing a memorial for veterans who died in the Soldiers’ Home outbreak. The state’s $56 million settlement followed a class-action lawsuit brought by about 80 veterans who were sickened by covid and a roughly equal number of families of veterans who died.

The state’s attorney general also brought criminal charges against Walsh and the home’s former medical director, David Clinton, in connection with their handling of the crisis. The two averted a trial and possible jail time this March by changing their not-guilty pleas, instead acknowledging that the facts of the case were sufficient to warrant a guilty finding.

An attorney representing Walsh and Clinton, Michael Jennings, declined to comment on queries from KFF Health News. He instead referred to legal proceedings in March, in which Jennings argued that “many nursing homes proved inadequate in the nascent days of the pandemic” and that “criminalizing blame will do nothing to prevent further tragedy.”

Nursing assistants sued the home’s leadership, too. The lawsuit alleged that, in addition to their symptoms of long covid, what the aides witnessed “left them emotionally traumatized, and they continue to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.”

The case was dismissed before trial, with courts ruling that the caretakers could have simply left their jobs. “Plaintiff could have resigned his employment at any time,” Judge Mark Mastroianni wrote, referring to Ablordeppey, the nursing assistants’ named representative in the case.

But the choice was never that simple, said Erica Brody, a lawyer who represented the nursing assistants. “What makes this so heartbreaking is that they couldn’t have quit, because they needed this job to provide for their families.”

‘Help Us To Retire’

Brody didn’t know of any cases in which staff at long-term nursing facilities successfully held their employers accountable for labor conditions in covid outbreaks that left them with mental and physical ailments. KFF Health News pored through lawsuits and called about a dozen lawyers but could not identify any such cases in which workers prevailed.

A Massachusetts chapter of the Service Employees International Union, SEIU Local 888, is looking outside the justice system for help. It has pushed for a bill — proposed last year by Judith García, a Democratic state representative — to allow workers at the state veterans home in Holyoke, along with its sister facility in Chelsea, to receive their retirement benefits five to 10 years earlier than usual. The bill’s fate will be decided in December.

Retirement benefits for Massachusetts state employees amount to 80 percent of a person’s salary. Workers qualify at different times, depending on the job. Police officers get theirs at age 55. Nursing assistants qualify once the sum of their time working at a government facility and their age comes to around 100 years. The state stalls the clock if these workers take off more than their allotted days for sickness or vacation.

Several nursing assistants at the Holyoke veterans home exceeded their allotments because of long-lasting COVID symptoms, post-traumatic stress, and, in Ragoonanan’s case, a brain aneurysm. Even five years would make a difference, Ragoonanan said, because, at age 56, she fears her life is being shortened. “Help us to retire,” she said, staring at the slippers covering her swollen feet. “We have bad PTSD. We’re crying, contemplating suicide.”

Certain careers are linked with shorter life spans. Similarly, economists have shown that, on average, people with lower incomes in the United States die earlier than those with more. Nearly 60 percent of long-term-care workers are among the bottom earners in the country, paid less than $30,000 — or about $15 per hour — in 2018, according to analyses by the Department of Health and Human Services and KFF, a health-policy research, polling, and news organization that includes KFF Health News.

Fair pay was among the solutions listed in the surgeon general’s report on burnout. Another was “hazard compensation during public health emergencies.”

If employers offer disability benefits, that generally entails a pay cut. Nursing assistants at the Holyoke veterans home said it would halve their wages, a loss they couldn’t afford.

“Low-wage workers are in an impossible position, because they’re scraping by with their full salaries,” said John Magner, SEIU Local 888’s legal director.

Despite some public displays of gratitude for health care workers early in the pandemic, essential workers haven’t received the financial support given to veterans or to emergency personnel who risked their lives to save others in the aftermath of 9/11. Talk show host Jon Stewart, for example, has lobbied for this group for over a decade, successfully pushing Congress to compensate them for their sacrifices.

“People need to understand how high the stakes are,” van Dernoot Lipsky said. “It’s so important that society doesn’t put this on individual workers and then walk away.”

Amy Maxmen is a KFF journalist.

Inspired by Boston landmarks

"IYKYK" (wood, plastics), by Christopher Abrams, in his show "IYKYK," at Boston Sculptors Gallery, Oct. 3-Nov. 3.

The famous sign at Kenmore Square, in Boston.

The gallery says:

“The show is a series of small-scale sculpture based on iconic landmarks and forgotten histories in the Boston area. While Abrams continues to concentrate on small-scale representational concerns, the artist revisits and redirects his focus, abandoning the intense fealty to detail that characterizes his earlier miniature efforts, in favor of finding essential, meaningful symbols and imagery.

“Taking inspiration from his hometown, Abrams draws on the events and visual vocabulary that create and distinguish the unique identity of Greater Boston. Selecting and amplifying elements of the local, shared visual fabric, Abrams weighs how seemingly minor details can allude to a rich, shared narrative.’’