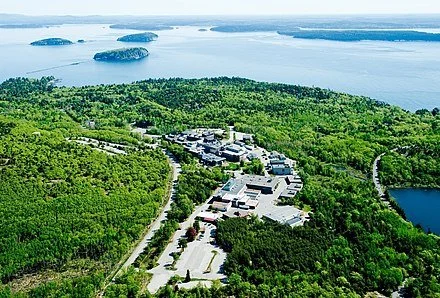

Jackson Lab's big expansion

Jackson Laboratory’s campus in Bar Harbor.

Edited from a New England Council report

The Jackson Laboratory, a nonprofit biomedical-research institution in Bar Harbor, Maine, has applied to build a 20,000-square-foot expansion.

The addition will expand the lab’s Rare Disease Translational Center, including providing more space for laboratories and offices. Earlier this year, Congress allocated $8 million to construct the new facility. The project’s total cost is expected to be $32.75 million, and the addition will consist of two stories with a mechanical penthouse. Each floor will have a footprint of about 9,200 square feet, with an additional 1,688-square-foot mechanical penthouse.

The goal is to complete the project by August 2026.

The Jackson Lab says:

“Our team serves those with rare disease by accelerating the pre-clinical phase. Our vision is to provide patients with an efficient path from diagnosis to therapy, allowing them to live longer, healthier lives.’’

Rick Gorvett: As climate worsens, should homeowners self-insure?

No matter where you live, there’s a good chance the weather’s getting wilder. In just the past few weeks, tornadoes have wreaked havoc on Midwest and Southern states, and large swaths of southern Florida were flooded. Globally, 2023 was the hottest year on record.

In addition to harming life and property, weather-related catastrophes have caused the cost of homeowners insurance to spike. Premiums have risen at rates well above general inflation.

In places such as Florida that are particularly exposed to natural disasters, homeowners insurance isn’t just expensive – it’s increasingly becoming difficult to find. That has caused some homeowners to go without it entirely.

More than 6 million American homeowners don’t have homeowners insurance, according to a recent analysis from the Consumer Federation of America. That’s about one out of every 14 homeowners in the country. Collectively, they have at least US$1.6 trillion in unprotected market value. That’s a lot of risk.

As a math professor and an expert in actuarial science, which deals in assessing risks, I’ve watched the mounting homeowners insurance crisis closely.

If catastrophic weather events continue to escalate, so-called “self-insurance” – buying no insurance and paying for any losses yourself – might be the only viable option for homeowners living in disaster-prone areas.

Why risk is getting more expensive

In general, the price of risk, as reflected by an insurance premium, is a function of the risk’s potential frequency and its severity. Potential frequency means the likelihood of a loss occurring, and severity means the financial cost associated with the loss.

So, increases in the frequency or severity of risks result in higher homeowners insurance premiums. The biggest catastrophic risks affecting homeowners insurance include hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, wildfires and winter storms.

Given climate change, it’s likely that many of these catastrophes will become stronger and more common, leading to higher insurance costs. In fact, this is already happening – although how much insurance companies are pricing in the cost of climate change, and whether it’s enough, is uncertain.

If you do opt to buy homeowners insurance, as more than 92% of American homeowners do, you should comparison shop for the best price and coverage. You can do this independently or through an agent or broker.

They may not differ much in their premium prices, however, given the emerging risks. And some insurers may be unwilling to write new policies, depending on where you live. For example, State Farm and Allstate have paused their writing of new homeowners insurance policies in some disaster-prone markets in California.

Choosing to self-insure

Instead of buying homeowners insurance, you may choose to self-insure. Finance experts consider self-insurance to be a legitimate risk management strategy. But that’s only if you choose it with full knowledge of the risk exposure and financial consequences.

Self-insurance is a common component of large organizations’ overall risk strategy. For example, as many as 33% of privately employed workers nationwide are insured by employer-sponsored, self-insured group health plans. For many organizations, self-insurance is also common for workers’ compensation insurance.

For those homeowners wealthy enough to absorb a major uninsured loss, it makes sense to consider self-insurance.

Of course, there are some caveats.

First, homeowners need to be realistic about their ability to respond to a significant uninsured loss. Having a thorough knowledge of your personal financial situation – or access to a qualified financial planner – is critical.

Second, self-insurance is likely to be viable only for homeowners who own their homes outright. If there is a mortgage on the property, purchase of an insurance policy is typically required to protect the lender.

And finally, it’s important to remember that homeowners insurance is a “multi-peril” policy, which includes liability coverage for accidents. While the size of a property loss might be limited to the value of that property, liability risk is potentially unlimited.

Without homeowners insurance, potential liability exposure should be addressed in some other way – for example, through risk-control efforts such as warning signs or limiting guests on the property, or through some type of stand-alone personal liability insurance policy.

How long will the insurance crunch last?

Most insurers try to maintain stable rates and premiums. But historically, most property-liability insurance has followed a multiyear underwriting cycle. This cycle, from the standpoint of the insurer, goes from a high-premium/low-loss ratio to a low-premium/high-loss ratio, and back again.

This stems from several factors, including price competition within the insurance industry and uncertainty associated with future losses. The result is that when it comes to homeowners insurance, affordability and availability problems are often just temporary. Ultimately, supply and demand adjust, with a new market equilibrium arising as a natural part of the cycle.

Whether this will be the case for current issues in homeowners insurance depends on a number of challenges facing homeowners. There’s some reason for pessimism: Mortgage rates have recently hit their highest levels in over 20 years, and in the meantime, prices in many areas have skyrocketed.

Meanwhile, in 2023, the National Association of Realtors Housing Affordability Index reached its lowest level in almost 40 years. And the future impact of climate change on homeowners insurance losses remains uncertain at best.

Amid all this uncertainty, one thing is clear: Being, or aspiring to be, a homeowner is a real challenge these days.

Rick Gorvett is a professor of mathematics and economics at Bryant University, in Smithfield, R.I.

Rick Gorvett does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

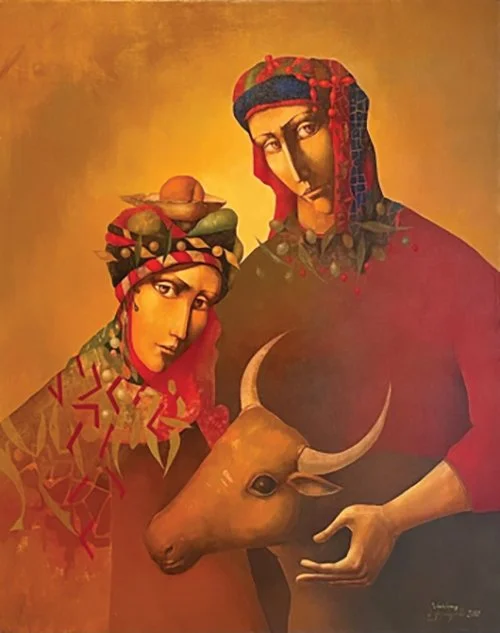

Very traditional marriage

“David and His Bride” (oil on canvas), by Vakhtang Sirunyan, in the show “Gandzaran! Notable Selections from Our Collection,’’ at the Armenian Museum of America, Watertown, Mass., through Aug. 4.

The museum explains:

“Drawing from the museum’s vaults—its ‘gandzaran’ —this exhibit showcases the development of Armenian art in the 20th and 21st centuries, from its origins in religious motifs to the Soviet period and its continuous reinterpretation among contemporary artists around the world.’’

William Morgan: It's time to retire stop signs

— Photo above by La Cara Salma

— Photos by William Morgan

Let’s face it, the days of the stop sign are over. The stop sign is an anachronism, as are simple courtesy and turn signals. Nobody pays attention to them anymore, so why do we keep them around? A stop sign can be confusing to, say, older people who might actually come to a complete stop, thereby creating a hazard and slowing the progress of all the other drivers who either ignore or do not recognize the purpose of the red metal octagon.

Stand at a busy street corner for a few minutes and count the number of cars that do not heed the stop sign. My experience of such an exercise invariably shows that a majority of motorists sail right through intersections without stopping; they might slow down for a moment, perhaps hesitating, vaguely remembering a forgotten but once ingrained habit. During a recent brunch at a restaurant on a busy Providence corner, I watched as nine out of ten cars failed to stop. The particular location is a block from an elementary school, yet the presence of crossing guard hardly seems make a dent in transgressions.

Rhode Islanders are certifiably among the nation’s worst drivers–the drivers least likely to abide by traffic rules. But I expect disobeying stop signs is a common American phenomenon–no one expects us to drive like the Swiss or the Swedes. Perhaps there are some national characteristics–anti-authoritarianism, visual impairment, stupidity–that make us want to transform a reasonable few extra seconds of pausing into a game of automotive chicken.

Maybe there’s a plot by insurance companies to raise premiums, and there’s is an army of lawyers who flood the airwaves and crowd the sides of highways with billboards asserting that they can monetize your car crash.

Eventually, I will get rear-ended by a distracted mother in her Ford Subdivision or a hedge-funder in his Mercedes Afrika Korps, or mauled by a super aggressive-looking pickup truck, the drivers all texting. Until then, I will try to retain my belief that obeying traffic rules is part of a greater social contract. Yet the failure to heed stop signs suggests a larger breakdown of society as a whole.

Like the use of cell phones while driving (illegal in my state), such actions point to a lack of connection with the world around you and your species. If you don’t make eye contact with a pedestrian, a bicyclist or another driver, you are closing down an opportunity to interact with another human, a fellow citizen. When I slow down or pull out of the way on a narrow street so that an oncoming car can pass through, I rarely get an acknowledgment, a wave of the hand, a mouthed thank you. I am just some unimportant loser in an 18-year-old Volvo who ought to give way to the driver of a hurrying urban assault vehicle on a self-important mission. My wife, however, says I am just invisible.

In neighboring Massachusetts, stop signs at dangerous intersections are getting blinking lights around their perimeters. This seems to me like the third stop light that was mandated on cars a few decades ago–and we know how effective they have been on cutting down on tailgaiting. Such well-intentioned gestures are only short-term bandages putting off the eventual removal of all these useless stop signs.

Let the all-out free-for-all begin.

William Morgan is an architectural writer based in Providence. His latest book is Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States.

From Hitler to Trump, the thirst for a dictator to quash perceived foes

A projected image of Trump, from behind a bulletproof shield, delivering his speech on Jan. 6, 2021, urging his followers, many of them violent, to march on the Capitol to overturn the election he lost.

And a hearty sieg heil!

Nazi rally in Nuremberg in 1934.

“History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.’’

— Quote attributed to Mark Twain (1835-1910)

You’ll hear some rhyming this week at the Republican National Convention, in Milwaukee.

Neo-fascist political commentator Nick Fuentes, in this logo, made contemporary use of the phrase “America First,’’ the isolationist movement before Pearl Harbor that included pro-Nazis, such as Charles Lindberg. He cited Trump and his presidency as an inspiration for his show.

Thoughts about beaches

Nauset Beach on Cape Cod, with eroding bluffs.

Popham Beach, Maine, on an evening in July.

Photo by Dirk Ingo Franke

View of Nantasket Beach, in Hull, Mass., in 1879, when it was a very popular resort for Bostonians.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

“Objects on the beach, whether men or inanimate things, look not only exceedingly grotesque, but much larger and more wonderful than they really are.’’

-- Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) in Cape Cod, published in 1865.

Sandy beaches, with dunes or bluffs behind, stony beaches and these days even disappearing beaches, draw us. I’ve lived near most major varieties.

Beaches invite long walks, and offer a wide-open view to the horizon, which we need in our all-too-indoors world. And they’re the best places for kite flying because they’re usually breezy; too bad that you don’t see as much kite flying these days. I mention in passing beaches as venues for sex. Bad manners.

They also offer surprises: The waves constantly bring in different things to look at – some beautiful, some hideous – maybe, if you’re unlucky, even a human body. Every day walking on a beach brings different revelations, especially when it’s stormy. You’ll find such treasures as colorful sea glass -- physically and chemically weathered glass found on salt-water beaches. There used to be a lot more before plastic (made from petrochemicals) took over much of the container business. Plastic bottles, etc., turn into microplastics that present a range of environmental woes.

Then there are skate-egg cases. But there are fewer interesting shells these days and, it seems, less driftwood. And far fewer horseshoe crab shells, in part because they’re being fished out for their blood for use in medical applications. You probably know that they aren’t real crabs, by the way, but, rather, related to spiders and scorpions. Creepy?

Then there are various kinds of seaweed, some of which are edible, and useful for other purposes, too, though they draw insects, some biting, to the beach, and can have a rank smell.

High summer on beaches thronged with people can be problematic. Best to go before Memorial Day and/or after Labor Day. Then you can hear the birds and the wind more than the yelps of vacationers; you’re more likely to avoid the screech of transitorily popular music, or cutting your feet on a beer can, and, if you’re casting for fish, less likely to catch someone in the eye.

I’ve been thinking a bit more about beaches these days because the last close relatives I’ve had on Cape Cod are selling their house in a village where we’ve had ancestors (many of them Quakers) since the 17th Century. There’s a beautiful sandy beach close by (though it’s eroding at an accelerating rate because of seas elevated by global-warming) that brought us many fine memories. The clean water is warm from late June to late September – in the 70s (F) – and there were/are graceful sand dunes we used to roll down as kids.

My paternal and laconic grandfather, who lived in West Falmouth after retirement, used to call the entire Cape “The Beach.’’

Hydrangeas bloom for several weeks.

— Photo by EoinMahon

Summer bloom bursts

How nice now to enjoy such spectacular blossoming of hydrangeas as distraction from so much grim news. Of course, most news in the media is grim: “If it bleeds it leads’’. Gotta turn it off now and then.

The mild and wet winter is being given much of the credit for the particularly vivid colors of these acid-and-coastal-loving bushes this summer, which can make walking around so cheery and make you forget that the most colorful time of the year is late spring and October, not mid-summer. There’s a great Robert Frost poem called “The Oven Bird,’’ that deals with this.

Now a lot of the blooms, which come in a range of colors, are fading.

‘Cancel space’

The Bearcamp River in South Tamworth, N.H., on the southern edge of the White Mountains

“No matter how tightly the body may be chained to the wheel of daily duties, the spirit is free, if it so pleases, to cancel space and to bear itself away from noise and vexation into the secret places of the mountains.’’

— Frank Bolles (1856-1894), writer and lawyer, in his book At the North of Beaucamp Water: Chronicles of a Stroller in New England

Inspired by Mid-Century Modern design

“Gioco Palla” (diptych) (oil on canvas), by Boston-based painter Susan Morrison-Dyke, in her show “A Roll of the Dice,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through July 28.

She says:

“Finding my inspiration in the sleek abstraction of Mid-Century Modern design, the inventiveness of cubism and the authenticity of primitive and ancient art, I often rely on intuition and spontaneity to guide my artistic process.’’

The gallery says:

“Morrison-Dyke’s vibrant abstract paintings juxtapose formal blocks of color with playfully drawn interpretations of natural and stylized forms.

“The improvisational quality of the work results from a decisive design structure, which underlies the artist’s use of inventive and painterly abstractions.’’

The Chapel at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, designed by Eero Saarinen, is a classic example of Mid-Century Modern design. It was opened in 1956.

— Photo by Daderot

Chris Powell: Extending medical insurance to illegal immigrants draws in more of them

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut's nullification of federal immigration law proceeded this month as state government extended its welfare system's medical insurance to illegal immigrant children by three years, from 12 and under to 15 and under. The children being added will be able to keep their state coverage until they turn 19 -- and maybe, as seems likely, by the time they turn 19 Connecticut will have extended eligibility to a higher age.

Such gradualism is how Gov. Ned Lamont and the Democratic majority in the General Assembly have been handling the issue for years now. They have been maintaining both that decency requires covering all illegal immigrant children and -- in contradiction -- that the state can afford to cover only a few thousand more every year. This gradualism obscures the budgetary and nullification issues enough that most people don't notice and make a fuss about them.

While the policy being pursued by state government may make political sense, it is still mistaken. Its logic is that Connecticut somehow can afford to lift all of Central America and much of the rest of the world out of poverty in the next decade, and it encourages more people to violate federal immigration law.

Advocates of extending the medical insurance to more illegal immigrant children note that even without such insurance Connecticut's hospitals will always have to treat illegal immigrant children when they come to emergency rooms with urgent conditions, and that when such patients or their guardians don't pay, hospitals essentially will transfer the expense to state government and patients who do pay for themselves.

But this rationale does not acknowledge that providing medical insurance to illegal immigrant children rewards and incentivizes illegal immigration to Connecticut and that if the state did not extend the insurance, the parents or guardians of the children being covered might relocate to other states providing coverage. It's not as if illegal immigrants in the United States have no choice but to live in Connecticut. Like everyone else they may look for the place where they are treated best.

While Governor Lamont supported the latest extension of insurance, when it took effect the other day he implied that he had some reservations about it, saying it should be accompanied by "comprehensive immigration reform." But of course it has not been accompanied by "comprehensive immigration reform," and the governor didn't specify what "comprehensive immigration reform" is.

Is it mass amnesty, making all illegal immigrants legal, as many other Democrats want?

Is it deporting all 12 million or so illegal immigrants estimated to be in the country, the objective that has been proclaimed by presidential candidate Donald Trump without an explanation of how the logistical difficulties would be met?

Is it to continue having open borders most of the time, as advocated by Connecticut U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy via the dishonest "compromise" legislation he proposed in February with Sens. James Lankford (R.-Okla.), and Kyrsten Sinema, the former Democrat and now nominal independent from Arizona?

In any case the millions of illegal and unvetted immigrants who have entered the country since President Biden took office are not an accident but policy, a policy of devaluing citizenship and hastening change in the country's demographics and its democratic and secular culture. Extending medical insurance to illegal immigrants -- on top of driver's licenses and other government identification documents, housing, and food subsidies -- is part of that policy. So is forbidding state and municipal police from assisting federal immigration agents, as Connecticut forbids them, thereby making itself a "sanctuary state."

If illegal immigration is never to be simply stopped and immigration law simply enforced, the country won't be a country anymore.

The United States long has welcomed immigration and should continue to do so. But immigration must be limited to what the country can assimilate in normal circumstances. A desperate national housing shortage, strain on hospitals, and schools overwhelmed with students who don't speak English signify the obliviousness to illegal immigration by both the federal government and state government.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Between the literal and abstract’

“Tokyo Moose” (acrylic and oil on canvas), by Patrick McCay, in his show “And She Feeds You Tea and Oranges That Come All the Way From China,’’ at Whistler House Museum of Art, Lowell, Mass.

The museum says:

“Patrick McCay’s work occupies the space between the literal and abstract. Skillfully orchestrated colors pepper the expressive surfaces of chosen icons. Grounded in a scaffold of remarkable drawings and an immediacy of gestural brushstrokes, he tempts and teases with a visual theatricality, adding the dignity of the ‘unknown’ to that which is all too well ‘known.’ McCay focuses his visual explorations within the imposed contours and attentive challenge of thematic expression.’’

Jordan Rau: The perils of nursing homes, in R.I. and elsewhere, ignoring minimum staffing rules

From Knight Family Foundation Health News

SMITHFIELD, Conn.

For hours, John Pernorio repeatedly mashed the call button at his bedside in the Heritage Hills nursing home in Rhode Island. A retired truck driver, he had injured his spine in a fall on the job decades earlier and could no longer walk. The antibiotics he was taking made him need to go to the bathroom frequently. But he could get there only if someone helped him into his wheelchair.

By the time an aide finally responded, he’d been lying in soiled briefs for hours, he said. It happened time and again.

“It was degrading,” said Pernorio, 79. “I spent 21 hours a day in bed.”

Payroll records show that during his stay at Heritage Hills, daily aide staffing levels were 25% below the minimums under state law. The nursing home said it provided high-quality care to all residents. Regardless, it wasn’t in trouble with the state, because Rhode Island does not enforce its staffing rule.

An acute shortage of nurses and aides in the nation’s nearly 15,000 nursing homes is at the root of many of the most disturbing shortfalls in care for the 1.2 million Americans who live in them, including many of the nation’s frailest old people.

They get festering bedsores because they aren’t turned. They lie in feces because no one comes to attend to them. They have devastating falls because no one helps them get around. They are subjected to chemical and physical restraints to sedate and pacify them.

California, Florida, Massachusetts, New York and Rhode Island have sought to improve nursing home quality by mandating the highest minimum hours of care per resident among states. But an examination of records in those states revealed that putting a law on the books was no guarantee of better staffing. Instead, many nursing homes operated with fewer workers than required, often with the permission of regulators or with no consequences at all.

“Just setting a number doesn’t mean anything if you’re not going to enforce it,” said Mark Miller, former president of the national organization of long-term care ombudsmen, advocates in each state who help residents resolve problems in their nursing homes. “What’s the point?”

Now the Biden administration is trying to guarantee adequate staffing the same way states have, unsuccessfully, for years: with tougher standards. Federal rules issued in April are expected to require 4 out of 5 homes to boost staffing.

The administration’s plan also has some of the same weaknesses that have hampered states. It relies on underfunded health inspectors for enforcement, lacks explicit penalties for violations, and offers broad exemptions for nursing homes in areas with labor shortages. And the administration isn’t providing more money for homes that can’t afford additional employees.

Serious health violations have become more widespread since covid-19 swept through nursing homes, killing more than 170,000 residents and driving employees out the door.

Pay remains so low — nursing assistants earn $19 an hour on average — that homes frequently lose workers to retail stores and fast-food restaurants that pay as well or better and offer jobs that are far less grueling. Average turnover in nursing homes is extraordinarily high: Federal records show half of employees leave their jobs each year.

Even the most passionate nurses and aides are burning out in short-staffed homes because they are stretched too thin to provide the quality care they believe residents deserve. “It was impossible,” said Shirley Lomba, a medication aide from Providence. She left her job at a nursing home that paid $18.50 an hour for one at an assisted living facility that paid $4 more per hour and involved residents with fewer needs.

The mostly for-profit nursing home industry argues that staffing problems stem from low rates of reimbursement by Medicaid, the program funded by states and the federal government that covers most people in nursing homes. Yet a growing body of research and court evidence shows that owners and investors often extract hefty profits that could be used for care.

Nursing home trade groups have complained about the tougher state standards and have sued to block the new federal standards, which they say are unworkable given how much trouble nursing homes already have filling jobs. “It’s a really tough business right now,” said Mark Parkinson, president and chief executive of one trade group, the American Health Care Association.

And federal enforcement of those rules is still years off. Nursing homes have as long as five years to comply with the new regulations; for some, that means enforcement would fully kick in only at the tail end of a second Biden administration, if the president wins reelection. Former President Donald Trump’s campaign declined to comment on what Trump would do if elected.

Persistent Shortages

Nursing home payroll records submitted to the federal government for the most recent quarter available, October to December 2023, and state regulatory records show that homes in states with tougher standards frequently did not meet them.

In more than two-thirds of nursing homes in New York and more than half of those in Massachusetts, staffing was below the state’s required minimums. Even California, which passed the nation’s first minimum staffing law two decades ago, has not achieved universal compliance with its requirements: at least 3½ hours of care for the average resident each day, including two hours and 24 minutes of care from nursing assistants, who help residents eat and get to the bathroom.

During inspections since 2021, state regulators cited a third of California homes — more than 400 of them — for inadequate staffing. Regulators also granted waivers to 236 homes that said workforce shortages prevented them from recruiting enough nurse aides to meet the state minimum, exempting them from fines as high as $50,000.

In New York, Gov. Kathy Hochul declared an acute labor shortage, which allows homes to petition for reduced or waived fines. The state health department said it had cited more than 400 of the state’s 600-odd homes for understaffing but declined to say how many of them had appealed for leniency.

In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed legislation in 2022 to loosen the staffing rules for all homes. The law allows homes to count almost any employee who engages with residents, instead of just nurses and aides, toward their overall staffing. Florida also reduced the daily minimum of nurse aide time for each resident by 30 minutes, to two hours.

Now only 1 in 20 Florida nursing homes are staffed below the minimum — but if the former, more rigorous rules were still in place, 4 in 5 homes would not meet them, an analysis of payroll records shows.

“Staffing is the most important part of providing high-quality nursing home care,” said David Stevenson, chair of the health policy department at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “It comes down to political will to enforce staffing.”\

The Human Toll

There is a yawning gap between law and practice in Rhode Island. In the last three months of 2023, only 12 of 74 homes met the state’s minimum of three hours and 49 minutes of care per resident, including at least two hours and 36 minutes of care from certified nursing assistants, payroll records show. One of the homes below the minimum was Heritage Hills Rehabilitation & Healthcare Center in Smithfield, where Pernorio, president of the Rhode Island Alliance for Retired Americans, went last October after a stint in a hospital.

“From the minute the ambulance took me in there, it was downhill,” he said in an interview.

Sometimes, after waiting an hour, he would telephone the home’s main office for help. A nurse would come, turn off his call light, and walk right back out, and he would push the button again, Pernorio reported in his weekly e-newsletter.

While he praised some workers’ dedication, he said others frequently did not show up for their shifts. He said staff members told him they could earn more flipping hamburgers at McDonald’s than they could cleaning soiled patients in a nursing home.

In a written statement, Heritage Hills did not dispute that its staffing, while higher than that of many homes, was below the minimum under state law.

Heritage Hills said that after Pernorio complained, state inspectors visited the home and did not cite it for violations. “We take every resident concern seriously,” it said in the statement. Pernorio said inspectors never interviewed him after he called in his complaint.

In interviews, residents of other nursing homes in the state and their relatives reported neglect by overwhelmed nurses and aides.

Jason Travers said his 87-year-old father, George, fell on the way to the bathroom because no one answered his call button.

“I think the lunch crew finally came in and saw him on the floor and put him in the bed,” Travers said. His father died in April 2023, four months after he entered the home.

Relatives of Mary DiBiasio, 92, who had a hip fracture, said they once found her sitting on the toilet unattended, hanging on to the grab bar with both hands. “I don’t need to be a medical professional to know you don’t leave somebody hanging off the toilet with a hip fracture,” said her granddaughter Keri Rossi-D’entremont.

When DiBiasio died in January 2022, Rhode Island was preparing to enact a law with nurse and aide staffing requirements higher than anywhere else in the country except Washington, D.C. But Gov. Daniel McKee suspended enforcement, saying the industry was in poor financial shape and nursing homes couldn’t even fill existing jobs. The governor’s executive order noted that several homes had closed because of problems finding workers.

Yet Rhode Island inspectors continue to find serious problems with care. Since January 2023, regulators have found deficiencies of the highest severity, known as immediate jeopardy, at 23 of the state’s 74 nursing homes.

Homes have been cited for failing to get a dialysis patient to treatment and for giving one resident a roommate’s methadone, causing an overdose. They have also been cited for violent behavior by unsupervised residents, including one who shoved pillow stuffing into a resident’s mouth and another who turned a roommate’s oxygen off because it was too noisy. Both the resident who was attacked and the one who lost oxygen died.

Bottom Lines

Even some of the nonprofit nursing homes, which don’t have to pay investors, are having trouble meeting the state minimums — or simply staying open.

Rick Gamache, chief executive of the nonprofit Aldersbridge Communities, which owns Linn Health & Rehabilitation in East Providence, said Rhode Island’s Medicaid program paid too little for the home to keep operating — about $292 per bed, when the daily cost was $411. Aldersbridge closed Linn this summer and converted it into an assisted living facility.

“We’re seeing the collapse of post-acute care in America,” Gamache said.

Many nursing homes are owned by for-profit chains, and some researchers, lawyers, and state authorities argue that they could reinvest more of the money they make into their facilities.

Bannister Center, a Providence nursing home that payroll records show is staffed 10% below the state minimum, is part of Centers Health Care, a New York-based private chain that owns or operates 31 skilled nursing homes, according to Medicare records. Bannister lost $430,524 in 2021, according to a financial statement it filed with Rhode Island regulators.

Last year, the New York attorney general sued the chain’s owners and investors and their relatives, accusing them of improperly siphoning $83 million in Medicaid funds out of their New York nursing homes by paying salaries for “no-show” jobs, profits above what state law allowed, and inflated rents and fees to other companies they owned. For instance, one of those companies, which purported to provide staff to the homes, paid $5 million to the wife of Kenny Rozenberg, the chain’s chief executive, from 2019 to 2021, the lawsuit said.

The defendants argued in court papers that the payments to investors and owners were legal and that the state could not prove they were Medicaid funds. They have asked for much of the lawsuit to be dismissed.

Jeff Jacomowitz, a Centers Health Care spokesperson, declined to answer questions about Bannister, Centers’ operations, or the chain’s owners.

Miller, the District of Columbia’s long-term care ombudsman, said many nursing home owners could pay better wages if they didn’t demand such high profits. In D.C., 7 in 10 nursing homes meet minimum standards, payroll records show.

“There’s no staffing shortage — there’s a shortage of good-paying jobs,” he said. “I’ve been doing this since 1984 and they’ve been going broke all the time. If it really is that bad of an investment, there wouldn’t be any nursing homes left.”

The new federal rules call for a minimum of three hours and 29 minutes of care each day per resident, including two hours and 27 minutes from nurse aides and 33 minutes from registered nurses, and an RN on-site at all times.

Homes in areas with worker shortages can apply to be exempted from the rules. Dora Hughes, acting chief medical officer for the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, said in a statement that those waivers would be “time-limited” and that having a clear national staffing minimum “will facilitate strengthened oversight and enforcement.”

David Grabowski, a health policy professor at Harvard Medical School, said federal health authorities have a “terrible” track record of policing nursing homes. “If they don’t enforce this,” he said, “I don’t imagine it’s going to really move the needle a lot.”

The KFF Health News data analysis focused on five states with the most rigorous staffing requirements: California, Florida, Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island.

To determine staffing levels, the analysis used the daily payroll journals that each nursing home is required to submit to the federal government. These publicly available records include the number of hours each category of nursing home employee, including registered nurses and certified nursing assistants, worked each day and the number of residents in each home. We used the most recent data, which included a combined 1.3 million records covering the final three months of 2023.

We calculated staffing levels by following each state’s rules, which specify which occupations are counted and what minimums homes must meet. The analysis differed for each state. Massachusetts, for instance, has a separate requirement for the minimum number of hours of care registered nurses must provide each day.

In California, we used state enforcement action records to identify homes that had been fined for not meeting its law. We also tallied how many California homes had been granted waivers from the law because they couldn’t find enough workers to hire.

For each state and Washington, D.C., we calculated what proportion of homes complied with state or district law. We shared our conclusions with each state’s nursing home regulatory agency and gave them an opportunity to respond.

This analysis was performed by senior KFFHealth News correspondent Jordan Rau, who wrote this article, and data editor Holly K. Hacker.

In Bellows Falls, Bug from the ‘70s;’ precontact petroglyphs

“Beep-Beep,’’ by Medora Hebert, at the Canal Street Gallery, Bellows Falls, Vt.

The Bellows Falls Petroglyph Site, an archaeological site containing panels of pre-European- contact Native American petroglyphs in Bellows Falls. They are a rarely seen assemblage of figures believed to be unique in New England.

Llewellyn King: Scotus mandates confusion, intense judicial power; myths about ‘faceless bureaucrats

Buildings in Washington, D.C., housing federal agencies.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Myths are powerful things. So powerful that one has been endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court and now has the federal government by the throat.

Its effects will be far-reaching and, at times, disastrous and dangerous. Although a conservative favorite, it will hurt business, in some cases, severely.

The myth is that the government is dominated by “faceless, unelected bureaucrats” with an agenda of their own. These bureaucrats, according to myth, are out to frustrate the will of Congress, avoid the courts and ignore their political masters.

In striking down the Chevron deference on June 28 – the actual case was Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo — the Supreme Court sided with critics of the bureaucracy, ending what has been an operational reality for 40 years.

The Chevron deference is a Reagan-area, bipartisan accommodation which recognized that when Congress makes laws in broad strokes and big declarations of intent, the intent often requires refinement of minute scientific detail, like parts per billion of carcinogens allowed in drinking water.

Under the Chevron deference, when Congress had been sloppy, or too general, in its legislation writing, the agencies were empowered to interpret the law and — with public and stakeholder input in the form of hearings and comment periods — make rules.

It is the crux of the administrative state. If those rules were seen to be “reasonable” they couldn’t be litigated: They got “deference.” Although they could be challenged, the implied immunity of deference was mostly honored.

Clinton Vince, who heads the U.S. energy practice at Dentons, the world’s largest law firm, told me that the Supreme Court has upheld Chevron 70 times and that it has been cited in cases 18,000 times. He was speaking on my PBS television program, “White House Chronicle.”

Now, many of the agency decisions, which affect everything from drugs and medical products’ safety to the protection of human health and the environment, to workplace safety, to aviation safety and to the supply of electricity will be made in myriads of court cases.

Vince said that while reasonable people will disagree on the extent of the national disruption, “I believe that there will be an avalanche of litigation by affected stakeholders of different ideologies and that an entirely different paradigm of agency regulation will occur when the courts, rather than the agencies, will be the dominant decision makers,” he said.

Under Chevron, the courts would write the fine print (promulgate is the term used) that Congress didn’t or was unqualified to define in its legislation.

This fine print, this rendition of what Congress intended, was implemented and seldom challenged in the courts because the understanding embodied in Chevron was that if the rules were reasonable the courts would stand back.

Conservative argument postulated that this rule-making in such areas as the environment, energy, health and labor favored the liberal biases of the permanent bureaucracy.

Charles Bayless, who has been president of two investor-owned electric utilities, in Arizona and Illinois, and of the West Virginia University Institute of Technology, and who has been a party to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission rule-makings, told me he fears widespread chaos, jammed courts and extensive “forum shopping.”

“Each side will find very liberal and very conservative circuits and find a plaintiff in that jurisdiction. As the judges cannot understand the science, the outcome is likely preordained,” Bayless said.

“Thus, the appeals courts will be jammed with appeals from jurisdictions with biased judges writing opinions where neither they nor the jury understand the science,” he said.

A judge in, say, Wyoming could be asked in one submission to rule on the safety — yes, the safety — of a treatment for malaria and in another on the allowable radioactive releases from a nuclear reactor. This is a recipe for confusion and bad law, which will affect business and the public in deleterious ways.

As someone who covered Washington for 50 years, I have to say that the bureaucracy gets a bad rap. It isn’t monolithic — as the word implies — and is made up of men and women, some of whom (as in any other large group) may be biased and unfit for what they do.

But it also has a huge number of hardworking, ordinary Americans. This is particularly so in agencies, such as the Food and Drug Administration and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which administer technologically and scientifically based law. I call them the “hard” agencies because they rely on scientific and engineering expertise in their operation.

It is pure myth that they constitute a swamp or that they have pre-set agendas. Oh, and they do have faces.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

His 'killing instinct'

Arthur Miller (1915-2005) at his wedding, in 1956, to his second wife, Marilyn Monroe (1926-1962). They were divorced in 1961.

“I don’t know, I just couldn’t bear the idea of people trying to destroy each other, ‘cause I sensed very early on that all real arguments are murderous. There was a killing instinct in there that I feared. So, I put it into the theater.”

—Arthur Miller, American playwright and essayist) and long-time resident of Roxbury, Conn.

Without a helmet

“Finding the Sweet Spot’’ (collage), by Essex, Conn.-based artist Molly Lund, in the show “Play, Pastimes and Recreation,’’ at Spectrum Art Gallery, Centerbrook, Conn., July 26-Sept. 14.

View from Essex Park

— Photo by Joe Mabel

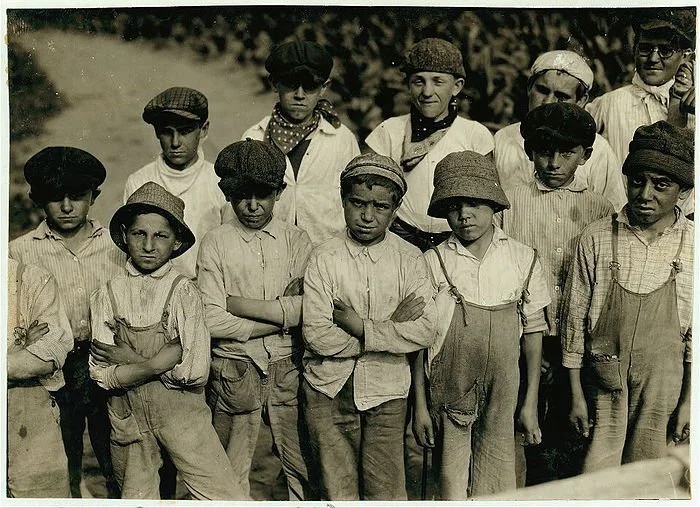

Conn. tobacco crop was once a big deal, if cancerous

Tobacco field with shade tents in East Windsor, Conn.

Field workers, all children, at the Goodrich Tobacco Farm near Gildersleeve, Conn., in 1917.

Text excerpted from a New England Historical Society report.

“The billowing white tents, once a feature of the northern Connecticut landscape, have almost disappeared, replaced by condos, parking lots and an Amazon warehouse. The vast acres of Connecticut Shade tobacco, 30,000 at their peak, have shrunk to just over 2,000.

“Cigar markers use Connecticut Shade as a wrapper – the outside of the cigar. It makes the finest wrapper in the world. As unlikely as it seems, Connecticut Shade ranks up there with tobacco from Cuba, Dominican Republic, Honduras, Mexico and Cameroon. Silky and golden, it looks good on a cigar.

“The highly prized tobacco is one of the priciest agricultural commodities on the planet. The leaves must be perfect – no holes or imperfections – for the ultimate appeal to the cigar smoker. It therefore requires more labor than other kinds of tobacco.

“The work begins in May, with weeding and transplanting seedlings. Then field workers fasten the plants to guide wires and spread cloth tents over them. As the plants grow, workers pick off shoots and tobacco worms. They harvest the leaves and bring them to sheds, where workers used to sew the leaves together and string them on wooden lathes. They’re hung up in the rafters where they cure, then they go to sorting sheds and warehouses.’’

Editor’s note: By the way, there’s a campy 1961 movie titled Parrish that’s set in the Connecticut tobacco country.

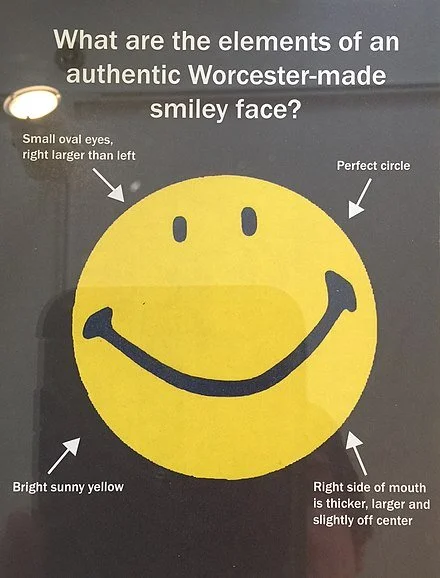

Happy and/or high in New England?

Hit this link for Smiley Face history.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Rankings of places and institutions are often full of baloney because they’re comparing apples and oranges, but not always.

Here’s one from last year that ranks, by certain criteria, the happiest states. This one ranked Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Connecticut, in that order, as the best.

Note that a cannabis company (!) did the rankings, in which, as in most rankings of states in health and other important criteria, the South is at the bottom.

Joy Organics said:

“There are lots of ideas as to what constitutes happiness for different people. With this research, we aimed to include a number of factors that either influence a state’s happiness or serve as indicators of it. Mental well being, support and suicide rates were weighted more heavily in the ranking, accounting for a larger proportion of each state’s overall score, as these were deemed to be the most important factors."

And easy access to marijuana products? Maybe not.

Away from it all

“Big Thompson Falls”,” (in Colorado) by Richard Sneary, in the annual “Green Mountain Watercolor Exhibition,’’ at the Galleries at Lareau Farm, Waitsfield, Vt., through July 20.