‘Sculptural perches’

“Perch,’’ by Jean Shin, at Appleton Farms, Ipswich, Mass. Studio shot.

Appleton Farms explains:

“‘Perch’ explores temporality (ecological and agricultural time) and regeneration. Bobolinks—songbirds who make the migratory journey from the Southern Hemisphere and whose populations are in decline—are the primary birds that use Appleton’s grasslands and hayfields as their nesting site. Shin created sculptural platforms made from Appleton’s fallen and dead trees that visitors can engage with, as they become participants in this critical monitoring throughout the project’s run. Within the nesting area, Shin will create sculptural perches made from fallen trees and salvaged copper in which male bobolinks can perch to search for mates and mark their territory.’’

Llewellyn King: Fusion power is looking more than dreamlike

Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) facility in Devens, Mass.

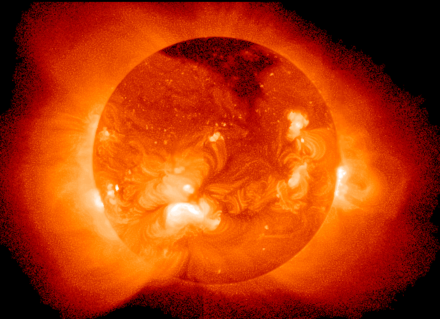

The Sun (here in X-ray) like other stars, is a natural fusion reactor, where stellar nucleosynthesis transforms lighter elements into heavier elements with the release of energy.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Fusion power, the Holy Grail of nuclear power for decades, may finally be within our grasp.

If the scientists and engineers at Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), a company with close ties to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Plasma Science and Fusion Center, are right, fusion is nearly ready for power market entry.

CFS, based in Devens, Mass., says it will be ready to ship its first devices in the early 2030s.

That is astounding news, which has been so long in the making that much of the nuclear industry has failed to grasp it.

I first started writing about fusion power in the 1970s. Having been on hand for many of its false starts, I was one of the doubters.

But after I visited the CFS factory in Devens and saw the precision production of the giant magnets, which are the key to the company’s system, I am on my way to being a believer.

I think that it’s likely that CFS can manufacture a device they can ship to users — utilities or big data centers — in the early 2030s. If so, the news is huge; it is a moment in science history like the first telephone call or the first incandescent light bulb.

Governments, grasping the potential for clean and essentially limitless power without weapons proliferation or radioactive waste, have lavished billions of dollars on fusion energy research worldwide. Intergovernmental effort in recent years has concentrated on the Joint European Torus (JET), which has wrapped up in Britain, and the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), a mega-project, involving 35 nations, is ongoing in France. Both are firmly in the category of scientific research.

But in the commercial world, there is a sense that fusion power is at hand, and many companies have raised money and are pressing forward. In the front of that pack is CFS.

There are two different technologies chasing the fusion dream: magnetic fusion energy (MFE) and inertial fusion energy (IFE). The former is where plasma at millions of degrees is contained in a magnetic bottle. The trick here isn’t in the plasma, but in the bottle.

A version of MFE, called the tokamak, is the technology expected to produce the first power plant. Worldwide dozens of startups are looking at fusion and in the United States, eight are considered frontline.

The other method, IFE, consists of hitting a small target pellet with an intense beam of energy, which can come from a laser or other device. It is still in the realm of research.

CFS has raised over $2 billion and is seen by many as the frontrunner in the fusion power stakes. It has been supported from its inception in 2018 by the Italian energy giant ENI. Bill Gates’s ubiquitous Breakthrough Energy is an investor. Altogether there are about 60 investors, mostly looking for a huge return as CFS begins to sell its devices.

According to Brandon Sorbom, co-founder and chief scientist at CFS, the big advance has been in the superconducting magnets that create containment bottles for plasma. He told me this had enabled them to design a device many times smaller than had previously been possible.

What makes CFS magnets different and revolutionary is the superconducting wire that is wound to make the magnets.

Think of the tape in a tape recorder, and you have an idea of the flat wire, called HTS, that is wound into each magnet. The HTS tape is first wound into VIPER cable, or NINT pancakes — acronyms for two types of magnet technology, developed by MIT in conjunction with CFS. Then the VIPER cable, or NINT pancakes, are assembled into magnets which make up the tokamak.

This superconducting wire enables a large amount of current to course through the magnet at many times the levels which have been unavailable previously. This means that the device can be smaller — about the size of a large truck.

The next stage is to complete the first full demonstration device at CFS, known as SPARC. Already, it is half-built and should become operational next year.

After that will come the first commercial fusion device, called ARC, which may be deployed in a decade. It will contain, as Sorbom said, “a star in a bottle using magnetic fields in a tokamak design,” and perchance bring abundant zero-carbon energy to users near you.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

whchronicle.com

The thrill is gone

Photo by J. Pinta (Redline2200)

By June our brook's run out of song and speed.

Sought for much after that, it will be found

Either to have gone groping underground

(And taken with it all the Hyla breed

That shouted in the mist a month ago,

Like ghost of sleigh-bells in a ghost of snow)—

Or flourished and come up in jewel-weed,

Weak foliage that is blown upon and bent

Even against the way its waters went.

Its bed is left a faded paper sheet

Of dead leaves stuck together by the heat—

A brook to none but who remember long.

This as it will be seen is other far

Than with brooks taken otherwhere in song.

We love the things we love for what they are.

— “Hyla Brook,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963). The brook was near the property where Frost lived with his family in 1900-1911

‘Whispers of the Wild’ in a resort town

“As the Sun Sets,’’ by Jessica Fligg, in the joint show with Linda McDermott,“Whispers of the Wild: Imagery of Land and Life,’’ at the WREN Gallery, Bethlehem, N.H., through June 23.

Bethlehem in 1883, as it was becoming a major summer resort.

Judith Graham: Older women’s health is woefully understudied

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

“This is an area where we really need to have clear messages for women and effective interventions that are feasible and accessible.’’

—Jo Ann Manson, chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston

Medical research has shortchanged women for decades. This is particularly true of older women, leaving physicians without critically important information about how to best manage their health.

Late last year, the Biden administration promised to address this problem with a new effort called the White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research. That inspires a compelling question: What priorities should be on the initiative’s list when it comes to older women?

Stephanie Faubion, director of the Mayo Clinic’s Center for Women’s Health, launched into a critique when I asked about the current state of research on older women’s health. “It’s completely inadequate,” she told me.

One example: Many drugs widely prescribed to older adults, including statins for high cholesterol, were studied mostly in men, with results extrapolated to women.

“It’s assumed that women’s biology doesn’t matter and that women who are premenopausal and those who are postmenopausal respond similarly,” Faubion said.

“This has got to stop: The FDA has to require that clinical trial data be reported by sex and age for us to tell if drugs work the same, better, or not as well in women,” Faubion insisted.

Consider the Alzheimer’s drug Leqembi, approved by the FDA last year after the manufacturer reported a 27% slower rate of cognitive decline in people who took the medication. A supplementary appendix to a Leqembi study published in the New England Journal of Medicine revealed that sex differences were substantial — a 12% slowdown for women, compared with a 43% slowdown for men — raising questions about the drug’s effectiveness for women.

This is especially important because nearly two-thirds of older adults with Alzheimer’s disease are women. Older women are also more likely than older men to have multiple medical conditions, disabilities, difficulties with daily activities, autoimmune illness, depression and anxiety, uncontrolled high blood pressure, and osteoarthritis, among other issues, according to scores of research studies.

Even so, women are resilient and outlive men by more than five years in the U.S. As people move into their 70s and 80s, women outnumber men by significant margins. If we’re concerned about the health of the older population, we need to be concerned about the health of older women.

As for research priorities, here’s some of what physicians and medical researchers suggested:

Heart Disease

Why is it that women with heart disease, which becomes far more common after menopause and kills more women than any other condition — are given less recommended care than men?

“We’re notably less aggressive in treating women,” said Martha Gulati, director of preventive cardiology and associate director of the Barbra Streisand Women’s Heart Center at Cedars-Sinai, a health system in Los Angeles. “We delay evaluations for chest pain. We don’t give blood thinners at the same rate. We don’t do procedures like aortic valve replacements as often. We’re not adequately addressing hypertension.

“We need to figure out why these biases in care exist and how to remove them.”

Gulati also noted that older women are less likely than their male peers to have obstructive coronary artery disease — blockages in large blood vessels —and more likely to have damage to smaller blood vessels that remains undetected. When they get procedures such as cardiac catheterizations, women have more bleeding and complications.

What are the best treatments for older women given these issues? “We have very limited data. This needs to be a focus,” Gulati said.

Brain Health

How can women reduce their risk of cognitive decline and dementia as they age?

“This is an area where we really need to have clear messages for women and effective interventions that are feasible and accessible,” said JoAnn Manson, chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and a key researcher for the Women’s Health Initiative, the largest study of women’s health in the U.S.

Numerous factors affect women’s brain health, including stress — dealing with sexism, caregiving responsibilities, and financial strain — which can fuel inflammation. Women experience the loss of estrogen, a hormone important to brain health, with menopause. They also have a higher incidence of conditions with serious impacts on the brain, such as multiple sclerosis and stroke.

“Alzheimer’s disease doesn’t just start at the age of 75 or 80,” said Gillian Einstein, the Wilfred and Joyce Posluns Chair in Women’s Brain Health and Aging at the University of Toronto. “Let’s take a life course approach and try to understand how what happens earlier in women’s lives predisposes them to Alzheimer’s.”

Mental Health

What accounts for older women’s greater vulnerability to anxiety and depression?

Studies suggest a variety of factors, including hormonal changes and the cumulative impact of stress. In the journal Nature Aging, Paula Rochon, a professor of geriatrics at the University of Toronto, also faulted “gendered ageism,” an unfortunate combination of ageism and sexism, which renders older women “largely invisible,” in an interview in Nature Aging.

Helen Lavretsky, a professor of psychiatry at UCLA and past president of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, suggests several topics that need further investigation. How does the menopausal transition impact mood and stress-related disorders? What nonpharmaceutical interventions can promote psychological resilience in older women and help them recover from stress and trauma? (Think yoga, meditation, music therapy, tai chi, sleep therapy, and other possibilities.) What combination of interventions is likely to be most effective?

Cancer

How can cancer screening recommendations and cancer treatments for older women be improved?

Supriya Gupta Mohile, director of the Geriatric Oncology Research Group at the Wilmot Cancer Institute at the University of Rochester, wants better guidance about breast cancer screening for older women, broken down by health status. Currently, women 75 and older are lumped together even though some are remarkably healthy and others notably frail.

Recently, the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force noted “the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening mammography in women 75 years or older,” leaving physicians without clear guidance. “Right now, I think we’re underscreening fit older women and overscreening frail older women,” Mohile said.

The doctor also wants more research about effective and safe treatments for lung cancer in older women, many of whom have multiple medical conditions and functional impairments. The age-sensitive condition kills more women than breast cancer.

“For this population, it’s decisions about who can tolerate treatment based on health status and whether there are sex differences in tolerability for older men and women that need investigation,” Mohile said.

Bone Health, Functional Health, and Frailty

How can older women maintain mobility and preserve their ability to take care of themselves?

Osteoporosis, which causes bones to weaken and become brittle, is more common in older women than in older men, increasing the risk of dangerous fractures and falls. Once again, the loss of estrogen with menopause is implicated.

“This is hugely important to older women’s quality of life and longevity, but it’s an overlooked area that is understudied,” said Manson of Brigham and Women’s.

Jane Cauley, a distinguished professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health who studies bone health, would like to see more data about osteoporosis among older Black, Asian, and Hispanic women, who are undertreated for the condition. She would also like to see better drugs with fewer side effects.

Marcia Stefanick, a professor of medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine, wants to know which strategies are most likely to motivate older women to be physically active. And she’d like more studies investigating how older women can best preserve muscle mass, strength, and the ability to care for themselves.

“Frailty is one of the biggest problems for older women, and learning what can be done to prevent that is essential,” she said.

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter.

Baseball and civilization

Connie Mack on an 1887 baseball card.

“Humanity is the keystone that holds nations and men together. When that collapses, the whole structure crumbles. This is as true of baseball teams as any other pursuit in life.’’

— Connie Mack (1862-1956), Major League catcher, manager and owner. He was a native of tiny East Brookfield, Mass.

The Keith Block, formerly the East Brookfield Municipal Building.

Mysteries of the past

Installation view of the show “Not a Story to Pass On,’’ of Jennifer Davis Carey and Scarlett Hoey, at the Danforth Art Museum, Framingham, Mass.

A matter of 'marital privacy'

“Late every night in Connecticut, lights go out in the cities and towns, and citizens by the thousands proceed zestfully to break the law.’’

—From the March 10, 1961, issue of Time magazine on the now long gone Connecticut law banning contraceptives. In 1879, Connecticut enacted a statute that banned the use of any drug, medical device or other instrument used to prevent contraception.

In its 1965 ruling Griswold v. Connecticut, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the U.S. Constitution protects the liberty of married couples to use contraceptives without government restriction. The Connecticut law, they decided, violated the "right to marital privacy".

Toward megalopolis on the ‘Vermonter’

“Southbound” (pastel), by Ann Wickham, in the show “White River Junction: A Pastel Perspective, ‘‘ at the Long River Gallery, White River Junction, Vt., through July 31.

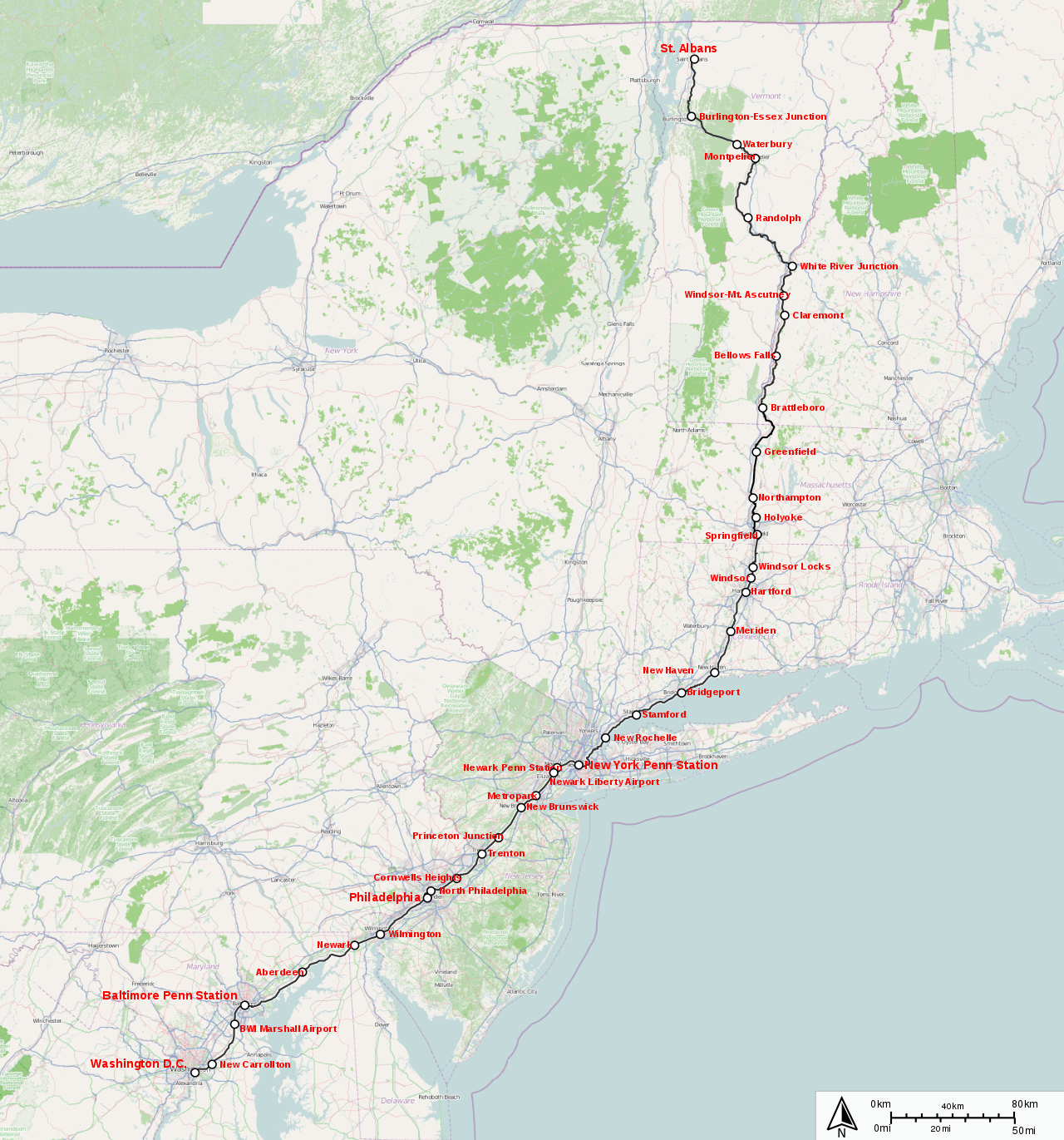

Map of Amtrak’s “Vermonter” route

— by Jkan997

Then better get off the road

“Sleepless” (acrylic on linen), by Boston-based artist J.S. Dykes, at the Cape Cod Museum of Art, Dennis, Mass., through July 14.

On the Bass River in Dennis.

Scargo Tower, at the top of Scargo Hill, in Dennis.

Chris Powell: Coaching a college basketball team is easier than legislating

Dan Hurley

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Celebrating Dan Hurley's decision this week to keep coaching the men's basketball team at the University of Connecticut, state House Speaker Matt Ritter confirmed a thought previously reserved for cynics.

That is, UConn's success with basketball is state government's great rationalization for giving the university whatever it wants financially year after year.

Ritter said: "I think there are times when legislators wonder, 'Why UConn? Why higher education?' There were comments about how we were giving so much money to UConn even this year. But Dan Hurley and [women's basketball coach] Geno Auriemma are four million more times popular than the most popular state legislator."

True. But then in a crucial respect the coaching jobs are much easier than those of state legislators -- at least the jobs of legislators who aspire to serve the public interest.

All the coaches have to do to please their constituents is win basketball games. Their players are united on this objective.

The coaches have luxurious contracts that indemnify themselves against failure, as was recently demonstrated by UConn's embarrassing and spectacularly expensive experience with former men's basketball coach Kevin Ollie.

There are no luxurious contracts for state legislators. They are elected for two-year terms with part-time salaries for what is often full-time work or close to it.

Their teams aren't unified. No, their constituents have a thousand objectives, many of them contradictory.

While UConn always gets plenty of money despite its many management failures and financial excesses, state legislators have to find money themselves, first to pay for government and then for their own campaigns.

But most of a legislator's constituents want someone else to pay for the goodies government gives them. As the economist Frederic Bastiat put it long ago, "Government is the great fiction by which everybody tries to live at the expense of everybody else."

And even when the public interest is clear, there is usually a venal special interest with enough politically active adherents to get their way amid the public's obliviousness.

The popularity of Hurley and Auriemma might crash as soon as they had to assemble a state budget or take a position on a controversial policy issue -- say, having 6-foot-4, 240-pound transgender players on high school and college women's basketball teams.

If many state legislators are the tools of special interests, it's because so few of their constituents pay attention that making any friends requires being a tool.

MONEY WON'T FIX SCHOOLS: What exactly does it mean that the state Education Department has instructed its commissioner to look into improving the finances of Hartford's ever-struggling school system?

Certainly there is much to improve. The academic performance of the city's students long has been terrible. Hartford's schools are facing a $40 million budget deficit and laying off hundreds of employees even as the system has tens of millions of dollars of emergency federal aid waiting to be spent.

Republicans in the state Senate have good questions about the state's intervention: Will state money be spent? Will Education Department employees be embedded in the Hartford school administration? Who will make decisions? Will labor contracts be reviewed? Will other struggling school systems in the state get similar evaluations? (They should.)

The most important question here may be whether schools can accomplish much of anything when most of their students lack responsible parents and are largely neglected. Since this may be the most important question, it has never been asked officially.

In any case there is a small indication of progress. Hartford school officials lately have been openly complaining that their schools are being drained financially by tuition transfers required by the regional "magnet" schools craze prompted in the Hartford area by the long-running Sheff v. O'Neill school desegregation case. The magnets are also draining the city's neighborhood schools of their better students. Measured by educational and integrational results, the Sheff case has been a billion-dollar disaster.

Money will never solve the education problem. It's a matter of far bigger issues that politics isn't ready to face.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years. (CPowell@cox.net) .

Llewellyn King: Will AI be mankind’s greatest adventure so far? There’s hope and fear

MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, in Cambridge, Mass. Its architecture can produce some of the anxiety that goes with the AI revolution. We’re in an increasingly strange world.

Some ways in which an advanced misaligned AI could try to gain more power.

Hit this link for video on the birth of artificial intelligence, whose founding as a discipline happened at Dartmouth College back in the summer of 1956.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

A new age in the human experience on Earth is underway. It is an age of change as profound — and possibly more so — than the Industrial Revolution with the steam engine introducing the concept of post-animal labor, known as shaft horsepower.

Artificial intelligence in this new age is infiltrating in all areas of human endeavor.

Some things, it will change totally, like work: It will end much menial work and a whole tranche of white-collar jobs. Some it will enhance our lives beyond imagination, such as in medicine and associated longevity.

Some AI will threaten, some it will annihilate.

It will test our understanding of the truth in what has become a post-fact world. The veracity of every assertion will be subject to investigation, from what happened in history to current election results. It will end much menial work and a whole tranche of white-collar jobs.

At the center of the upheaval in AI is electricity. It is the one essential element — the obedient ingredient — for AI.

Electricity is essential for the computers that support AI. But AI is putting an incalculable strain on electric supply.

The United States Energy Association, at its annual meeting, learned that a search on Google today uses a tenth of the electricity as the same search on ChatGPT.

Across the world, data centers are demanding an increasing supply of uninterruptible electricity 24/7. Utilities love this new business, but they fear that they won’t be able to service it going forward.

Fortunately AI is a valuable tool for utilities, and they are beginning to employ it increasingly in their operations, from customer services to harnessing distributed resources in what are called virtual power plants, to such things as weather prediction, counting dead trees for fire suppression, and mapping future demand.

Electricity is on the verge of a new age. And new technologies, in tandem with the relentless growth in AI use, are set to overhaul our expectations for electricity generation and increase demand for it.

Fusion power, small modular reactors, viable flexible storage in the form of new battery technology and upgraded old battery technology, better transmission lines, doubling the amount of power that can be moved from where it is made to where it is desperately needed are all on the horizon, and will penetrate the market in the next 10 years.

Synchronizing new demand with new supply is yet to happen, but electricity provision is on the march as inexorably as is AI. Together they hold the keys to a new human future.

A new book by Omar Hatamleh, a gifted visionary, titled This Time It’s Different, lifts the curtain on AI. Hatamleh, who is chief AI officer for NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, in Greenbelt, Md., says, “This time, it truly is different … Witness AI’s awakening, revealing its potential for both awe-inspiring transformation and trepidation.”

Hatamleh organized NASA’s first symposium on AI on June 11 at Goddard. Crème de la crème in AI participants came from OpenAI, Google, Microsoft, Nvidia, Qantm AI, Boeing and JP Morgan.

The consensus view was, to my mind, optimistically expressed by Pilar Manchon, Google’s senior director of AI, who said she thought that this was the beginning of humankind’s greatest adventure. The very beginning of a new age.

A bit of backstage criticism was that the commercial pressure for the tech giants to get to market with their generative AI products has been so great that they have been releasing them before all the bugs have been ironed out — hence some of the recent ludicrous search results, like the one from this question, “How do you keep the cheese on pizza?" The answer, apparently, was with “glue.”

However, these and other hallucinations won’t affect the conquering march of AI, everyone agreed.

Government regulation? How do you regulate something that is metamorphosing second by second?

A word about Hatamleh: I first met him when he was chief engineering innovation officer at NASA in Houston. He was already thinking about AI in his pursuit of off-label drugs to treat disease, and his desire to cross-reference data to find drugs and therapies that worked in one situation, but hadn’t been tried in another, especially cancer. This is now job No. 1 for AI.

During Covid, he wrangled 73 global scientists to produce a seminal report in May 2020, “Never Normal,’' which predicted with eerie accuracy how Covid would affect how we work, play, socialize and how life would change. And it has. A mere foretaste of AI?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

In a beautiful but sometimes grim region

“Pears,’’ by Audrey Shachnow, in the show’”, through Oct. 20, “Sculpture at The Mount’,’ the former (mostly) summer estate, in Lenox, Mass., in the Berkshires, of Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Edith Wharton (1862-1937). Ms. Wharton wrote a grim classic novel titled Ethan Frome about characters in the Berkshires.

The Mount staff says:

“‘Sculpture at The Mount’ showcases a diverse range of sculptures of varying scale and media produced by emerging and internationally established artists. This immersion of art in the natural world is free and open for the public to explore.’’

Liberate the fish? Keeping the pond less than ‘great’

Fish ladder, dam and waterfall at the Ipswich (Mass.) Mills Historic District, with mill pond, dating to the 17th Century, behind it.

— Photo by Mmangan333

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Here’s a quintessentially New England story about a heated debate in the Massachusetts North Shore town of Ipswich over whether to take down the Ipswich Mills Dam and fish ladder. The current dam was built in 1908, but there’s been a dam there since the 17th Century. It’s a reminder of the town’s industrial past. The idea, which seems to be supported by the majority of town residents, is to let the Ipswich River flow freely again, with associated environmental benefits, including better fishing and flood control.

But many love the pond that the dam created -- just to look at it and its waterfall, as well as for the skating and, I suppose, swimming, that it provided.

Lots of dams were built (and rebuilt) from colonial days to the early 20th Century to create waterfalls to power mills in New England towns large and small – at first to mill corn and for sawmills -- and many of us like those historic reminders, though few of the remaining mills serve any practical purpose anymore. But of course letting the rivers flow freely (when beavers allowed it), as they did when Native Americans lived along them, is much more “historic.’’

By the way, my parents lived for a few years on a mill pond in Norwell, Mass. The size of the pond could be adjusted by raising or lowering a board at the dam. The idea was to keep the pond at under 10 acres. If it got bigger than that, it would be classified under state law as a “great pond,’’ to which the public would have access.

'Deconstructing and rebuilding'

“Heart Relic” (conte and charcoal on paper, fabric, thread, found wood, soil), by Luba Shapiro Grenader, in her show “Lament & Renewal: Restringing the Heart, Reviving the Self,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, July 5-28.

The artist, based on the Massachusets North Shore and an immigrant from Russia, says:

“This work is a contemplation on personal loss and global change. Seeing those close to me suffer through illness and pain is excruciating; global suffering echoes this personal grief. While I find beauty in the act of drawing, I find solace in deconstructing and rebuilding. Threads make connections between the drawn elements and beyond – connecting the physical and ethereal. Cloth reimagines the drawings by mending the forms and extending the images.’’

What the Lobster Institute does

Lobsters awaiting purchase in Trenton, Maine

— Photo by Billy Hathorn

Edited from a New England Council article

ORONO, Maine

“The University of Maine has named Maine native and UMaine graduate Christina Cash to head up its Lobster Institute. Cash had served as the interim director since last summer, succeeding previous executive director Richard Wahle, who retired. Cash has been with the Institute since 2021, serving as assistant director of communication and outreach before coming into the interim role.

“Cash previously served as an advancement officer at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences and as program and development director at the Frances Perkins Center. She expressed her goals for the Lobster Institute, which include expanding student opportunities and programs at the Darling Marine Center, in Walpole.

“‘It is an honor to be in this position as a liaison between industry and the university,’ Cash said. ‘There’s so much going on in the lobster world right now and I look forward to collaborating with partners from industry, management and academia on research that can help the fishery.’

“Established in 1987, the Lobster Institute has been a center for discovery, innovation, and outreach for the University of Maine regarding the sustainability of the vital American lobster fishery for the U.S. and Canada. Research projects over the years have included an analysis of how rapid Arctic change has impacted fisheries and fishing communities, supporting research into lobster byproducts, and a study on how commercial lobstering data can be used to inform offshore wind farm developments. Serving as UMaine’s laboratory for marine research, Darling has undergone a $5.2 million waterfront infrastructure improvement project to enhance its research and business incubator projects.’’

Charles Colgan: Warming seas are slamming coastal economies

MIDDLEBURY, Vt.

Ocean-related tourism and recreation supports more than 320,000 jobs and US$13.5 billion in goods and services in Florida. But a swim in the ocean became much less attractive in the summer of 2023, when the water temperatures off Miami reached as high as 101 degrees Fahrenheit (37.8 Celsius).

The future of some jobs and businesses across the ocean economy have also become less secure as the ocean warms and damage from storms, sea-level rise and marine heat waves increases.

Ocean temperatures have been heating up over the past century, and hitting record highs for much of the past year, driven primarily by the rise in greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels. Scientists estimate that more than 90% of the excess heat produced by human activities has been taken up by the ocean.

That warming, hidden for years in data of interest only to oceanographers, is now having profound consequences for coastal economies around the world.

Understanding the role of the ocean in the economy is something I have been working on for more than 40 years, currently at the Center for the Blue Economy of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies. Mostly, I study the positive contributions of the ocean, but this has begun to change, sometimes dramatically. Climate change has made the ocean a threat to the economy in multiple ways.

The dangers of sea-level rise

One of the big threats to economies from ocean warming is sea-level rise. As water warms, it expands. Along with meltwater from glaciers and ice sheets, thermal expansion of the water has increased flooding in low-lying coastal areas and put the future of island nations at risk.

In the U.S., rising sea levels will soon overwhelm Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana and Tangier Island in Chesapeake Bay.

Flooding at high tide, even on sunny days, is becoming increasingly common in places such as Miami Beach; Annapolis, Maryland; Norfolk, Virginia; and San Francisco. High-tide flooding has more than doubled since 2000 and is on track to triple by 2050 along the country’s coasts.

Satellite and tide gauge data show sea-level change from 1993 to 2020. National Climate Assessment 2023

Rising sea levels also push salt water into freshwater aquifers, from which water is drawn to support agriculture. The strawberry crop in coastal California is already being affected.

These effects are still small and highly localized. Much larger effects come with storms enhanced by sea level.

Higher sea level can worsen storm damage

Warmer ocean water fuels tropical storms. It’s one reason forecasters are warning of a busy 2024 hurricane season.

Tropical storms pick up moisture over warm water and transfer it to cooler areas. The warmer the water, the faster the storm can form, the quicker it can intensify and the longer it can last, resulting in destructive storms and heavy downpours that can flood cities even far from the coasts.

When these storms now come in on top of already higher sea levels, the waves and storm surge can dramatically increase coastal flooding.

What Hurricane Hugo’s flooding would look like in Charleston, S.C., with today’s higher sea levels.

Tropical cyclones caused more than $1.3 trillion in damage in the U.S. from 1980 to 2023, with an average cost of $22.8 billion per storm. Much of that cost has been absorbed by federal taxpayers.

It is not just tropical storms. Maine saw what can happen when a winter storm in January 2024 generated tides 5 feet above normal that filled coastal streets with seawater.

A winter storm that hit at high tide sent water rushing into streets in Portland, Maine, in January 2024.

What does that mean for the economy?

The possible future economic damages from sea-level rise are not known because the pace and extent of rising sea levels are unknown.

One estimate puts the costs from sea-level rise and storm surge alone at over $990 billion this century, with adaptation measures able to reduce this by only $100 billion. These estimates include direct property damage and damage to infrastructure such as transportation, water systems and ports. Not included are impacts on agriculture from saltwater intrusion into aquifers that support agriculture.

Marine heat waves leave fisheries in trouble

Rising ocean temperatures are also affecting marine life through extreme events, known as marine heat waves, and more gradual long-term shifts in temperature.

In spring 2024, one third of the global ocean was experiencing heat waves. Corals are struggling through their fourth global bleaching event on record as warm ocean temperatures cause them to expel the algae that live in their shells and give the corals color and provide food. While corals sometimes recover from bleaching, about half of the world’s coral reefs have died since 1950, and their future beyond the middle of this century is bleak.

Healthy coral reefs serve as fish nurseries and habitat. These schoolmaster snappers were spotted on Davey Crocker Reef near Islamorada in the Florida Keys. Jstuby/wikimedia, CC BY

Losing coral reefs is about more than their beauty. Coral reefs serve as nurseries and feeding grounds for thousands of species of fish. By NOAA’s estimate, about half of all federally managed fisheries, including snapper and grouper, rely on reefs at some point in their life cycle.

Warmer waters cause fish to migrate to cooler areas. This is particularly notable with species that like cold water, such as lobsters, which have been steadily migrating north to flee warming seas. Once-robust lobstering in southern New England has declined significantly.

How three fish and shellfish species migrated between 1974 and 2019 off the U.S. Atlantic Coast. Dots shows the annual average location. NOAA

In the Gulf of Alaska, rising temperatures almost wiped out the snow crabs, and a $270 million fishery had to be completely closed for two years. A major heat wave off the Pacific coast extended over several years in the 2010s and disrupted fishing from Alaska to Oregon.

This won’t turn around soon

The accumulated ocean heat and greenhouse gases in the atmosphere will continue to affect ocean temperatures for centuries, even if countries cut their greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050 as hoped. So, while ocean temperatures fluctuate year to year, the overall trend is likely to continue upward for at least a century.

There is no cold-water tap that we can simply turn on to quickly return ocean temperatures to “normal,” so communities will have to adapt while the entire planet works to slow greenhouse gas emissions to protect ocean economies for the future.

Charles Colgan is director of Research for the Center for the Blue Economy at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Middlebury (Vt.)

Charles Colgan receives funding from several sources including NOAA and Lloyds of London. He was an author of the 5th National Climate Assessment chapter on oceans and the 4th California Climate Assessment chapter on coasts and oceans.

Taking it underground, away from the horse manure

Photo of the opening, on Sept. 1, 1897, of the first subway in the United States, a segment of the Green Line tunnel between Park Street and Boylston stations.

Horse-drawn beer wagon in Boston in early 20th Century.

Loneliness and landscape

Video still from Lake Valley, by American artist Rachel Rose, at Burlington (Vt.) City Arts.

The gallery says Lake Valley is a “visually rich animated video incorporating themes from children’s literature to create a dreamlike story about loneliness and imagination.’’

She looks at how mankind’s changing relationship to landscape has shaped storytelling and belief systems.

Burlington is sited spectacularly on Lake Champlain.