They did what they had to do

Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885), in his official presidential portrait, painted in 1875. He was, of course, the greatest Civil War general, and while his presidential reputation was sullied by corruption by some people in his administration, historians in recent years have raised their view of his two terms in office. The ancestors of Grant’s father emigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony from England in the 1630’s.

The greenish-yellow area has been expanding north at an accelerating rate in the past few decades. The climate of New England was considerably colder than now during “The Little Ice Age,’’ 1300-1850.

“They [the Pilgrim Fathers] fell upon an ungenial climate, where there were nine months of winter and three months of cold weather and that called out the best energies of the men, and of the women too, to get a mere subsistence out of the soil, with such a climate. In their efforts to do that they cultivated industry and frugality at the same time—which is the real foundation of the greatness of the Pilgrims.’’

From the speech by Ulysses S. Grant at a New England Society Dinner in New York on Dec. 22, 1880.

Llewellyn King: Cynically denigrating the news media has become a mainstay — attacking the messenger rather than the message

Outside the Reuters news service building in Manhattan

Newspapers "gone to the Web" in California

— Photo by SusanLesch

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

In the 1990s, someone wrote in The Weekly Standard — it may well have been Matt Labash — that for conservatives to triumph, all they had to do was to attack the messenger rather than the message. His advice was to go after the media, not the news.

Attacking the messenger was all well and good for the neoconservatives, but their less-thoughtful successors, MAGA supporters, are killing the messenger.

The news media— always identified as the “liberal media” (although much of the news media are right wing) — are now often seen, due to relentless denigration, as a force for evil, a malicious contestant on the other side.

No matter that there is no liberal media beyond what has been fabricated from political ectoplasm. Traditionally, most news proprietors have been conservative and many, but not most reporters, have been liberal.

It surprises people to learn that when you work in a large newsroom, you don’t know the political opinions of most of your colleagues. I have worked in many newsrooms over the decades and tended to know more about my colleagues’ love lives than their voting preferences.

This philosophy of “kill the messenger” might work briefly but down the road, the problem is no messenger, no news, no facts. The next stop is anarchy and chaos — you might say, politics circa 2024.

Add to that social media and their capacity to spread innuendo, half-truth, fabrication and common ignorance.

There is someone who writes to me almost weekly about the failures of the media — and I assume, ergo, my failure — and he won’t be mollified. To him, that irregular army of individuals who make a living reporting are members of a pernicious cult. To him, there is a shadow world of the media.

I have stopped remonstrating with him on that point. On other issues, he is lucid and has views worth knowing on such subjects as the Middle East and Ukraine.

That poses the question: How come he knows about these things? The answer, of course, is that he reads about them, saw/heard the news on television or heard it on radio.

Reporters in Gaza and Ukraine risk their lives, and sometimes lose them, to tell the world what is going on in these and other very dangerous places. No one accuses them of being left or right of center.

But send the same journalists to cover the White House, and they are assumed to be unreliable propagandists, devoid of judgment, integrity or common decency, so enslaved to liberalism that they will twist everything to suit a propaganda purpose.

That thought is on display every time Rep. Elise Stefanik (R.-N.Y.), an avid Trumper, is interviewed on TV. Stefanik attacks the interviewer and the institution. Her aim is to silence the messenger and leave the impression that she isn’t to be trifled with by the media, shades of Margaret Thatcher. But I interviewed “The Iron Lady,” and I can say she answered questions, hostile or otherwise.

Stefanik’s recent grandstanding on TV hid her flip-flop on the events on Jan. 6, 2021, and failed to tell us what she would do if she were to win the high office she clearly covets.

I have been too long in the journalist’s trade to pretend that we are all heroes, all out to get the truth. But I have observed that taken together, journalists tell the story pretty well, to the best of their own varied abilities.

We make mistakes. We live in terror of that. An individual here and there may fabricate — as Boris Johnson, a former British prime minister, did when he was a correspondent in Brussels. Some may, indeed, have political agendas; the reader or listener will soon twig that.

The political turmoil we are going through is partly the result of media denigration. People believe what they want to believe; they can seize any spurious supposition and hold it close as a revealed truth.

You can, for example, believe that ending natural-gas development in the United States will lead to carbon reduction worldwide, or you can believe that the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection with loss of life and the trashing of the nation’s great Capitol Building was an act of free speech.

One of the more dangerous ideas dancing around is that social media and citizen journalists can replace professional journalists. No, no, a thousand times no! We need the press with the resources to hire excellent journalists to cover local and national news, and to send, or station, staff around the world.

Have you seen anyone covering the news from Ukraine or Gaza on social media? There is commentary and more commentary on social media sites, all based on the reporting of those in danger and on the spot.

This is a trade of imperfect operators, but it is an essential one. For better or for worse, we are the messengers.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

No engineers need inspect

“Harlem Bridge” (oil on canvas), by Anthony Dyke, a Norwich,, Vt., native who lives in Boston, at the “One Plus One’’ show at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Feb. 25.

Clear 'em out

Edited from a Wikipedia report:

The Suffolk County Courthouse, now formally the John Adams Courthouse, in Pemberton Square, in Boston. It houses the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and the Massachusetts Appeals Court. Built in 1893, it was the major work of Boston's first city architect, George Clough, and is one of the city's few surviving late 19th-Century monumental civic buildings.

“In a lesser chamber of Suffolk County Courthouse on a day in early August, 1965 – the hottest day of the year – a Boston judge slammed down his heavy gavel, and its pistol-like report threw the room into disarray. Within a few minutes, everyone had gone – judge, court reporters, blue-shirted police, and a Portuguese family dressed as if for a wedding to witness the trial of their son.’’

— From the short story “Palais de Justice,’’ by Mark Helprin (born 1947), American-Israeli writer

Amy Maxmen: Right wingers' battle against science and facts imperils public health

The American Institute for Economic Research, in the wealthy Berkshires town of Great Barrington, Mass. The right-wing think tank has been a center of anti-science activism, at least when the science is defended by Democrats.

— Photby Dariusz Jemielniak ("pundit")

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

Rates of routine childhood vaccination in America hit a 10-year low in 2023. That, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, puts about 250,000 kindergartners at risk for measles, which often leads to hospitalization and can cause death. In recent weeks, an infant and two young children have been hospitalized amid an ongoing measles outbreak in Philadelphia that spread to a day care center.

It’s a dangerous shift driven by a critical mass of people who now reject decades of science backing the safety and effectiveness of childhood vaccines. State by state, they’ve persuaded legislators and courts to more easily allow children to enter kindergarten without vaccines, citing religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs.

Growing vaccine hesitancy is just a small part of a broader rejection of scientific expertise that could have consequences ranging from disease outbreaks to reduced funding for research that leads to new treatments. “The term ‘infodemic’ implies random junk, but that’s wrong,” said Peter Hotez, a vaccine researcher at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas. “This is an organized political movement, and the health and science sectors don’t know what to do.”

Changing views among Republicans have steered the relaxation of childhood vaccine requirements, according to the Pew Research Center. Whereas nearly 80% of Republicans supported the rules in 2019, fewer than 60% do today. Democrats have held steady, with about 85% supporting. Mississippi, which once boasted the nation’s highest rates of childhood vaccination, began allowing religious exemptions last summer. Another leader in vaccination, West Virginia, is moving to do the same.

An anti-science movement picked up pace as Republican and Democratic perspectives on science diverged during the pandemic. Whereas 70% of Republicans said that science has a mostly positive impact on society in 2019, less than half felt that way in a November poll from Pew. With presidential candidates lending airtime to anti-vaccine messages and members of Congress maligning scientists and pandemic-era public health policies, the partisan rift will likely widen in the run-up to November’s elections.

Dorit Reiss, a vaccine policy researcher at the University of California Law San Francisco, draws parallels between today’s backlash against public health and the early days of climate change denial. Both issues progressed from nonpartisan, fringe movements to the mainstream once they appealed to conservatives and libertarians, who traditionally seek to limit government regulation. “Even if people weren’t anti-vaccine to start with,” Reiss said, “they move that way when the argument fits.”

Even certain actors are the same. In the late ’90s and early 2000s, a right-wing think tank, the American Institute for Economic Research, undermined climate scientists with reports that questioned global warming. The same institute issued a statement early in the pandemic, grandly called the “Great Barrington Declaration.” It argued against measures to curb the disease and advised everyone — except the most vulnerable — to go about their lives as usual, regardless of the risk of infection. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, warned that such an approach would overwhelm health systems and put millions more at risk of disability and death from COVID. “Allowing a dangerous virus that we don’t fully understand to run free is simply unethical,” he said.

Another group, the National Federation of Independent Business, has fought regulatory measures to curb climate change for over a decade. It moved on to vaccines in 2022 when it won a Supreme Court case that overturned a government effort to temporarily require employers to mandate that workers either be vaccinated against covid or wear a face mask and test on a regular basis. Around 1,000 to 3,000 COVID deaths would have been averted in 2022 had the court upheld the rule, one study estimates.

Politically charged pushback may become better funded and more organized if public health becomes a political flashpoint in the lead-up to the presidential election. In the first few days of 2024, Florida’s surgeon general, appointed by Ron DeSantis, the former Republican and still Florida governor, called for a halt to use of mRNA covid vaccines as he echoed DeSantis’s incorrect statement that the shots have “not been proven to be safe and effective.” And vaccine skeptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who is running for president as an independent, announced that his campaign communications would be led by Del Bigtree, the executive director of one of the most well-heeled anti-vaccine organizations in the nation and host of a conspiratorial talk show. Bigtree posted a letter on the day of the announcement rife with misinformation, such as a baseless rumor that covid vaccines make people more prone to infection. He and Kennedy frequently pair health misinformation with terms that appeal to anti-government ideologies like “medical freedom” and “religious freedom.”

A product of a Democratic dynasty, Kennedy’s appeal appears to be stronger among Republicans, a Politico analysis found. DeSantis said he would consider nominating Kennedy to run the FDA, which approves drugs and vaccines, or the CDC, which advises on vaccines and other public health measures. Another fotmer Republican candidate for president, Vivek Ramaswamy, had vowed to gut the CDC should he win.

Today’s anti-science movement found its footing in the months before the 2020 elections, as primarily Republican politicians rallied support from constituents who resented such pandemic measures as masking and the closure of businesses, churches, and schools. Then-President Donald Trump, for example, mocked Joe Biden for wearing a mask at the presidential debate in September 2020.

Democrats fueled the politicization of public health, too, by blaming Republican leaders for the country’s soaring death rates, rather than decrying systemic issues that rendered the U.S. vulnerable, such as underfunded health departments and severe economic inequality that put some groups at far higher risk than others. Just before Election Day, a Democratic-led congressional subcommittee released a report that called the Trump administration’s pandemic response “among the worst failures of leadership in American history.”

Republicans launched a subcommittee investigation into the pandemic that sharply criticizes scientific institutions and scientists once seen as nonpartisan. On Jan. 8 and 9, the group questioned Anthony Fauci, M.D., director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in 1984-2022 and a leading infectious-disease researcher. Without evidence, committee member Marjorie Taylor Greene (R.-Ga.) accused Fauci of supporting research that created the coronavirus in order to push vaccines: “He belongs in jail for that,” Greene, a vaccine skeptic, said. “This is like a, more of an evil version of science.”

Taking a cue from environmental advocacy groups that have tried to fight strategic and monied efforts to block energy regulations, Hotez and other researchers say public health needs supporters knowledgeable in legal and political arenas. Such groups might combat policies that limit public health power, advise lawmakers, and provide legal counsel to scientists who are harassed or called before Congress in politically charged hearings.

Other initiatives aim to present the scientific consensus clearly to avoid both-sidesism, in which the media presents opposing viewpoints as equal when, in fact, the majority of researchers and bulk of evidence point in one direction. Oil and tobacco companies used this tactic effectively to seed doubt about the science linking their industries to harm.

Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center, at the University of Pennsylvania, said the scientific community must improve its communication. Expertise, alone, is insufficient when people mistrust the experts’ motives. Indeed, nearly 40% of Republicans report little to no confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interest.

In a study published last year, Jamieson and colleagues identified attributes the public values beyond expertise, including transparency about unknowns and self-correction. Researchers might have better managed expectations around covid vaccines, for example, by emphasizing that the protection conferred by most vaccines is less than 100% and wanes over time, requiring additional shots, Jamieson said. And when the initial covid vaccine trials demonstrated that the shots drastically curbed hospitalization and death but revealed little about infections, public health officials might have been more open about their uncertainty.

As a result, many people felt betrayed when COVID vaccines only moderately reduced the risk of infection. “We were promised that the vaccine would stop transmission, only to find out that wasn’t completely true, and America noticed,” said Rep. Brad Wenstrup (R.-Ohio), chair of the Republican-led coronavirus subcommittee, at a July hearing.

Jamieson also advises repetition. It’s a technique expertly deployed by those who promote misinformation, which perhaps explains why the number of people who believe the anti-parasitic drug ivermectin treats covid more than doubled over the past two years — despite persistent evidence to the contrary. In November, the drug got another shoutout at a hearing where congressional Republicans alleged that the Biden administration and science agencies had censored public health information.

Hotez, author of a new book on the rise of the anti-science movement, fears the worst. “Mistrust in science is going to accelerate,” he said.

And traditional efforts to combat misinformation, such as debunking, may prove ineffective.

“It’s very problematic,” Jamieson said, “when the sources we turn to for corrective knowledge have been discredited.”

Amy Maxmen is a Kaiser Family Health News reporter.

Find shelter where you can

From Chiffon Thomas’s show “The Cavernous,’’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Conn., through March 17.

The museum says:

“Chiffon Thomas’s first solo museum exhibition will unveil a new body of work, including the artist’s first public sculpture. Thomas’s interdisciplinary practice, spanning embroidery, collage, sculpture, drawing, performance, and installation, examines the ruptures that exist where race, gender expression, and biography intersect. Thomas’s practice is informed by his background in education, percussion, and stop motion animation, as well as a childhood steeped in religion.’’

In Ridgefield’s rather spiffy downtown

— Photo by Doug Kerr

A physician’s memoir of a son’s and his own early-onset cancer

Sidney Farber, M.D. (1903-1973), of Children’s Hospital, Boston, with a patient. Dr. Farber, a pediatric pathologist, is regarded as the father of modern chemotherapy. The famed Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, in Boston, is named for him and philanthropist Charles Dana. Some of Dr. George H. Beauregard’s book, Reservation for 9, occurs at Dana-Farber.

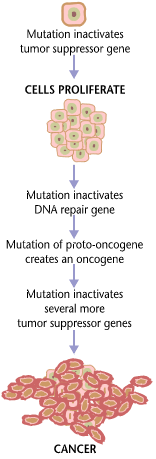

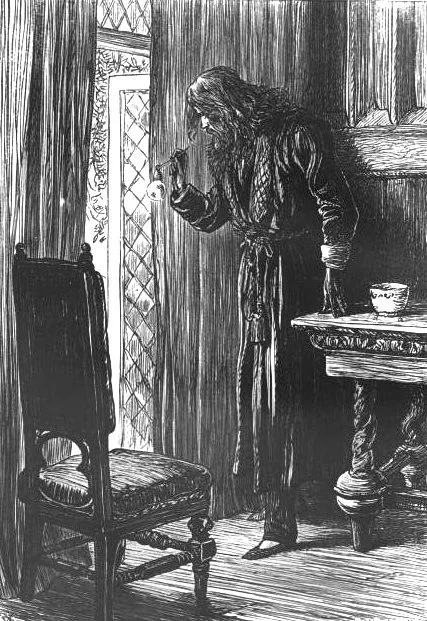

Numerous cell signaling pathways are disrupted in the development of cancer.

— Graphic by Roadnottaken

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I’ve been watching a physician/health-care executive friend, George H. Beauregard, prepare a book, yet to be published, titled Reservation for 9, that’s both a memoir and a medical saga, most of it set in Greater Boston.

The book tells how he and his son Patrick developed different advanced-stage early-onset cancers (early onset defined as cancers diagnosed in patients under 50), creating seismic changes in their lives, and those of their whole colorful nuclear family of six, that accompanied their illnesses. It’s a story about a complex family history, fear, grief and hope, along with the science and institutions of medicine, and provides much insight for others battling the disease.

There has been an alarming global increase in the incidence of cancer affecting younger adults. Patrick’s colorectal cancer was diagnosed when he was 29, and it killed him at 32, but not before he became an inspiring national spokesman for other victims. Dr. Beauregard, for his part, was diagnosed with bladder cancer at age 49 but is now apparently cured.

Patrick’s story continues to be cited in national news media, including recently in The Wall Street Journal.

Appearing as a guest on the Today Show on March 10, 2020, he said:

“In a situation like this, your mind can either liberate you or essentially incarcerate you...and you choose what to make of it.’’

“I don’t see the point in being negative in this. Negativity is only going to bring on more negativity. I choose to have a positive outlook and always have hope, and I don’t see why you would ever decide not to.”

Results from The Reproducibility Project: Cancer biology suggest most studies of the cancer research sector may not be replicable.

‘Getting back my humanity’

Carmichael Hall on the Rez Quad at Tufts

—Photo by Jellymuffin40

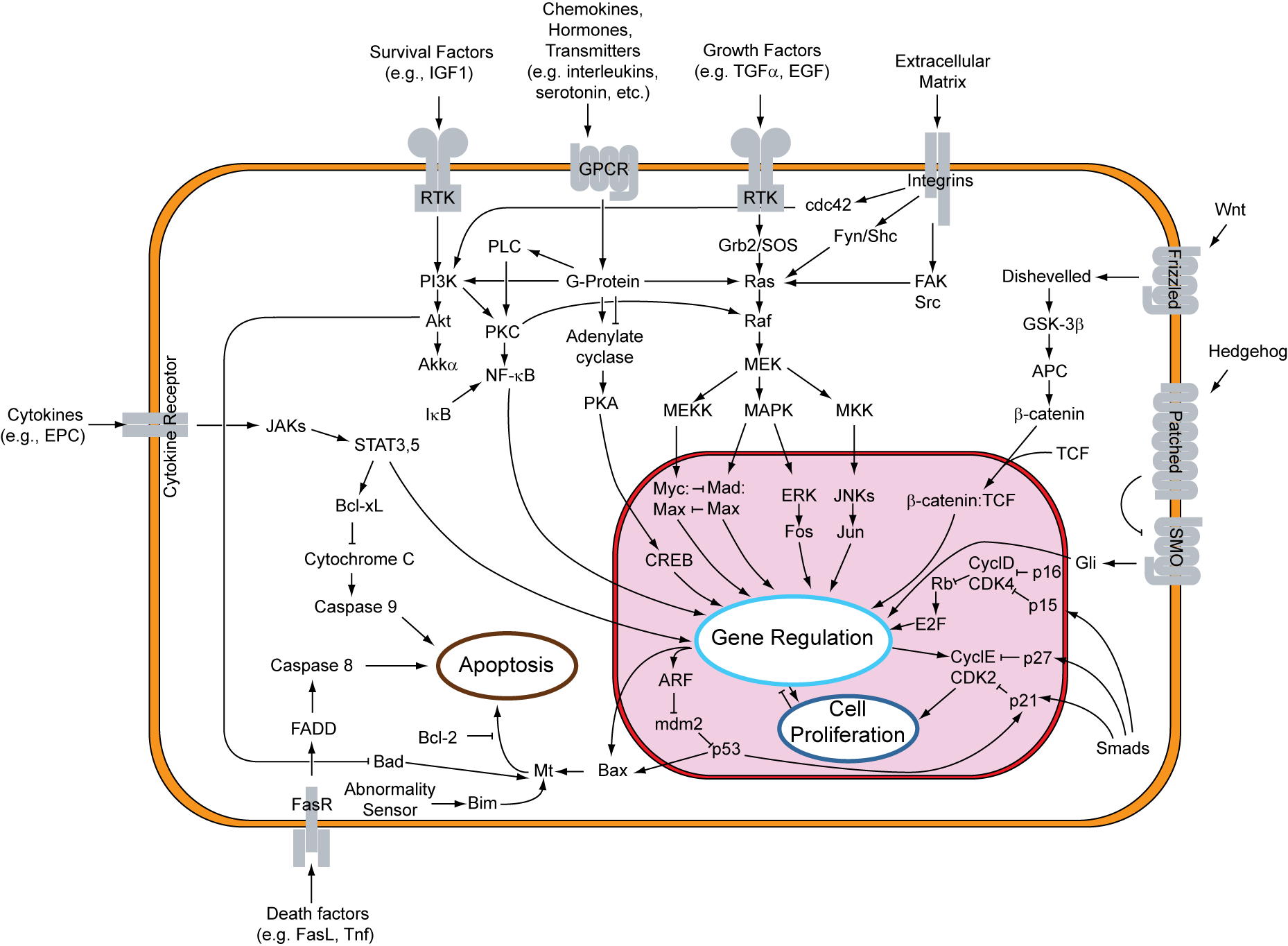

Tufts College circa 1854, on Walnut Hill, soon after its founding, in 1852.

Edited from a report by the New England Council, based on a Boston Globe story

“An initiative by Tufts University, has achieved remarkable success in recent years by allowing inmates to pursue and complete a college education. The Tufts University Prison Initiative at the Tisch College (TUPIT), at Tufts’s main campus, in Medford, Mass., established in 2016, fosters collaboration between Tufts faculty, students, and both incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. This partnership aims to address challenges related to mass incarceration and racial justice. TUPIT also provides a unique opportunity for students who begin their studies while incarcerated to continue and complete their education on the Tufts campus after their release.

“TUPIT was created by Hilary Binda, a senior lecturer at Tufts, and now the program’s executive director. TUPIT also includes the Tufts Educational Reentry Network, MyTERN, an accredited one-year college and reentry program for people post-incarceration.

“One of the program’s graduates, 33-year-old Juan Pagan, said in his graduation speech, ‘Professors affirming that I am worthy and have something positive to offer society is the greatest gift I have ever received. I now know that I can be an asset to my family and community because [the program] helped me gain back that ineffable part of me that prison repressed — my humanity.’’

Success enough?

Skylands, now Martha Stewart’s summer place in Seal Harbor, Maine, was built for auto mogul Edsel Ford.

“Don't give up. Defend your ideas, but be flexible. Success seldom comes in exactly the form you imagine.”

“So the pie isn't perfect? Cut it into wedges. Stay in control, and never panic.’’

― Martha Stewart (born 1941), lifestyle mogui

Travel, time and place

Left ,“Interior V ‘‘ (photograph on aluminum), by Rebecca Skinner. Right, “W. 42nd St.’’ (oil on panel), by Chris Plunkett, in the group show “Travelling,’’ at Fountain Street Fine Art, Boston.

The gallery says:

“‘Travelling’ suggests a sojourn to a destination in some form or another, and the concept of ‘place’ is examined along multiple vectors by this group of artists. Rebecca Skinner’s interior/exterior photographs of abandoned places contain a textural richness revealing a morphological study not merely of paint, brick, and wood, but also the chronological layers of story. The vibrant cityscapes that fluidly leap from the brush of Chris Plunkett….{T}he intensity of his palette turns recognizable metropolitan scenes into urban spectacles out of fondly remembered dreams.’’

Weird wonderland

“Iris Spring” (acrylic and oil canvas), by Maine-based artist Emilie Stark-Menneg, in the show “New England Now,’’ at the Shelburne (Vt.) Museum, May 11 to Oct.

— Photo courtesy of artist

The museum says:

“From Nathaniel Hawthorne to Stephen King, the depths of the psyche and the surreal have long fascinated New England artists. Twelve multidisciplinary artists from the region tap into a rich tapestry of mediums and techniques to create their perceptions of the ethereal grounded in topics of mythology, environmentalism, the ideals of beauty, transformation, and gender and cultural identity.’’

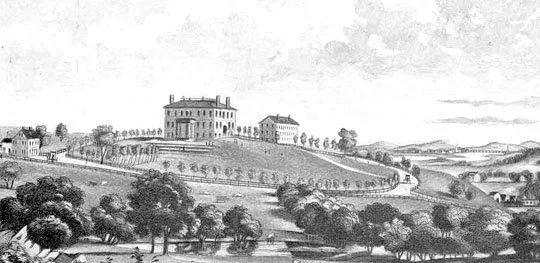

The House of the Seven Gables, in Salem, Mass., whose oldest part dates to 1668. It inspired Nathaniel Hawthorne to write his Gothic novel of the same name.

1875 illustration of Clifford Pyncheon in The House of the Seven Gables.

Mary Lhowe: The ‘lunchbox’ from offshore wind turbines

Text from ecoRI News article by Mary Lhowe

“Opponents of offshore wind offer different reasons for their position: fear of impacts on the marine ecology; fear of loss of income for fishers; fear of loss of tourism dollars and private property values due to the sight of the turbines on the horizon.

“The cloudy threat of wind projects off the New England coast comes with a golden — not silver — lining. That gold would arrive in the form of millions of dollars contractually promised to communities by developers in the form of mitigations, sometimes through a mechanism called host community or good neighbor agreements.

Even the towns and historic property owners who dread wind farms but yearn for funds to do worthy projects could be excused for reacting to mitigation deals in similar fashion to the character Gaz in the movie The Full Monty. Watching men audition for a new amateur dance troupe, Gaz observes the impressive talents of one particular auditioner, and mutters, “Gentlemen, the lunchbox has landed.”

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Wherever you go, there you are

“Then I was back in it.

The War was on. Outside,

in Worcester, Massachusetts,

were night and slush and cold,

and it was still the fifth

of February, 1918.’’

— From “In the Waiting Room,’’ by Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979)

Be like a mushroom

“Symbiosis,’’ by Natick, Mass.-based Rebecca McGee Tuck, in Boston Sculptors Gallery’s “Confluence’’ group show Feb. 1-Feb. 25.

The gallery says:

“Rebecca McGee Tuck takes inspiration from fungi, nature's own recyclers, digesting organic matter and replenishing the soil. Her mushroom sculpture erupts in a raucous celebratory array of colorful materials, urging us to emulate the mushroom’s mutual partnership and adopt mushroom-like practices—reduce, reuse, repurpose, and recycle—to sustain a harmonious relationship with our planet.’’

The former town seal of Natick, depicting John Eliot preaching to the Indians, set over a book representing the first Algonquian Bible.

Chris Powell: Conn.’s foolish EV promotion program

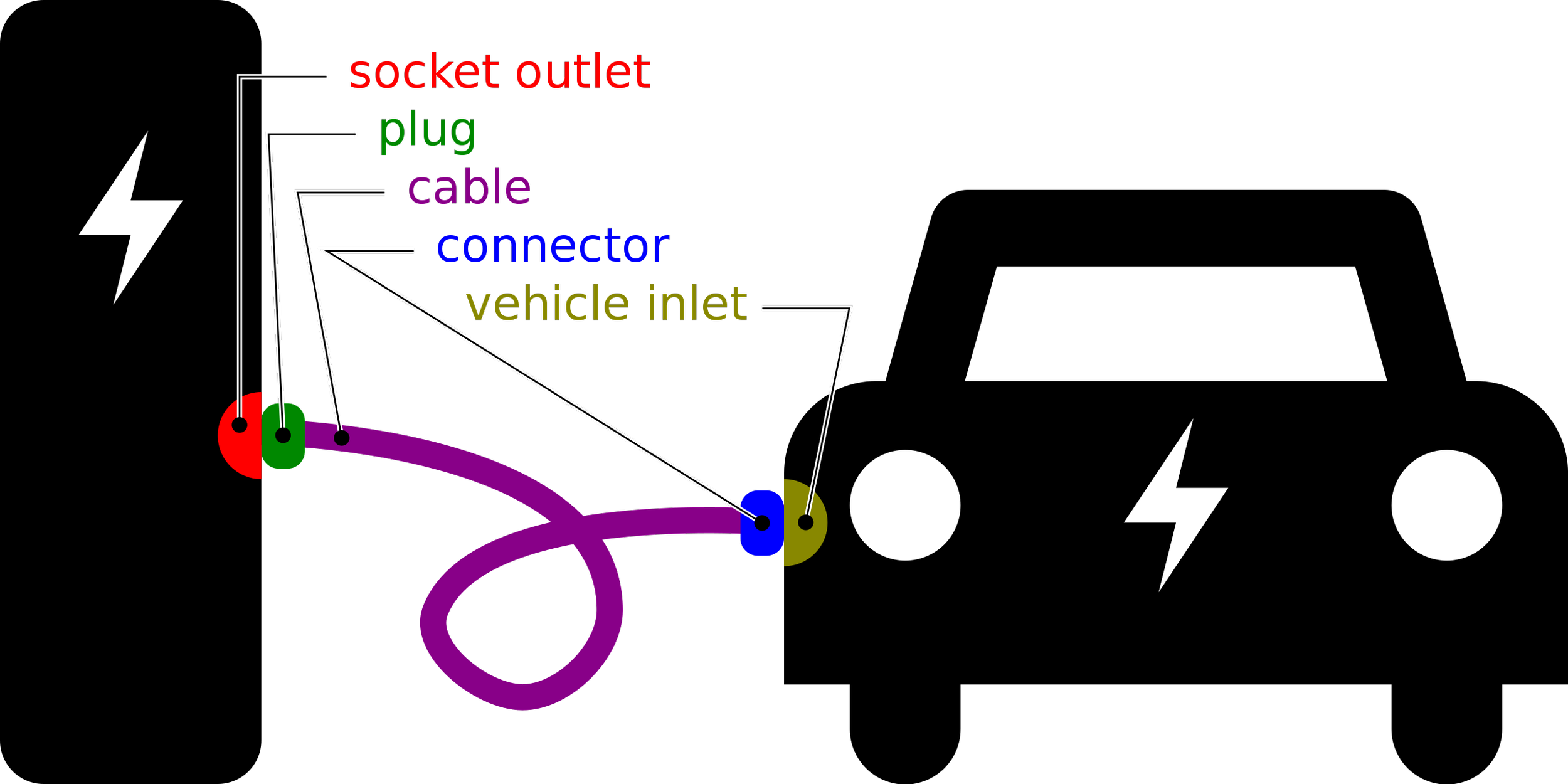

Graphic by Mliu92

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont and leaders of the Democratic majority in the General Assembly are planning to call a special session of the legislature next week to enact the strict California standards for auto emissions that were declined by the General Assembly's Regulations Review Committee in November. Back then two Democratic legislators on the committee from working-class districts seemed to understand that the California standards, outlawing sale of new gasoline-powered cars as of 2035, would leave the working class much poorer than the elites who can afford to toy with electric vehicles.

The governor is said to be giving assurances to legislators, especially those from racial and ethnic minority groups, that the ban on new gas-powered cars could be postponed by new legislation if the performance of electric cars doesn't improve as much as is hoped and if the necessary huge expansion of the state's electricity grid and production doesn't proceed fast enough. The governor and other advocates of the California standards insist that mass conversion to electric cars is inevitable.

But if electric cars are inevitable because they will be so good that everyone will demand them, why must consumer choice be prohibited? Why must Connecticut commit to an expansion of its electricity grid that will cost billions of dollars when there is no plan for it and no idea of how it is to be financed?

The inadequacy of electric vehicles was powerfully demonstrated by the recent frigid weather across the country, with thousands of EVs stranded because batteries don't hold their charges in extreme cold and charging stations are not nearly as common as stations only selling gasoline. And would the people of Connecticut approve outlawing new gasoline-powered cars in another 11 years if they had to decide right now on how to pay the conversion costs? Of course not.

The California standards legislation is mainly a lot of politically correct posturing to lock Connecticut into a future that almost certainly will not turn out exactly as hoped. It is a "buy now, pay later" scheme whose cost is open-ended.

Repealing or postponing the California standards if things don't progress as hoped won't be so easy. By that time, various interest groups will have sprung up to profit from the new policy whether it's working or not and they may be influential enough to block any changes.

Hearst Connecticut newspapers reporter and columnist Dan Haar has noted the special tawdriness of the special session idea. The Democrats, Haar writes, want to enact the California standards before the legislature's regular session begins in February, while the public is not paying close attention and public hearings won't be required.

Before anything is put into law, the governor and other advocates of the California standards should offer a detailed plan and specify its costs and its method of financing, thereby allowing the public to make an informed decision while there is still a choice about paying.

Besides, Connecticut has far more compelling claims on public policy and public finance than whatever its gasoline-powered cars may be contributing to "climate change." Nothing Connecticut or even the whole country can do with auto emissions will come close to offsetting the carbon dioxide and pollutants that inevitably will be put into the atmosphere in coming decades by China, India, and the rest of the developing world.

State government has been prattling about equalizing, integrating, and improving public education at least since the state Supreme Court decision in Horton v. Meskill, in 1977, and 47 years and tens of billions of dollars in extra expense later nothing of substance has changed. Indeed, in recent years Connecticut's per-pupil costs have risen even as school enrollment and student performance have declined.

On top of that, homelessness and crime now are rising in the state amid other signs of social disintegration.

So why should anyone think that state government will succeed with a similarly grandiose project, conversion to electric cars, and that even if it was successful it would make any practical difference anyway?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

And healthily ignore reality

“Withstanding the cold {in New England} develops vigor for the relaxing days of spring and summer. Besides, in this matter as in many others, it is evident that nature abhors a quitter.”

― Arthur C. Crandall, in New England Joke Lore: The Tonic of Yankee Humor

‘As Covid morphed’

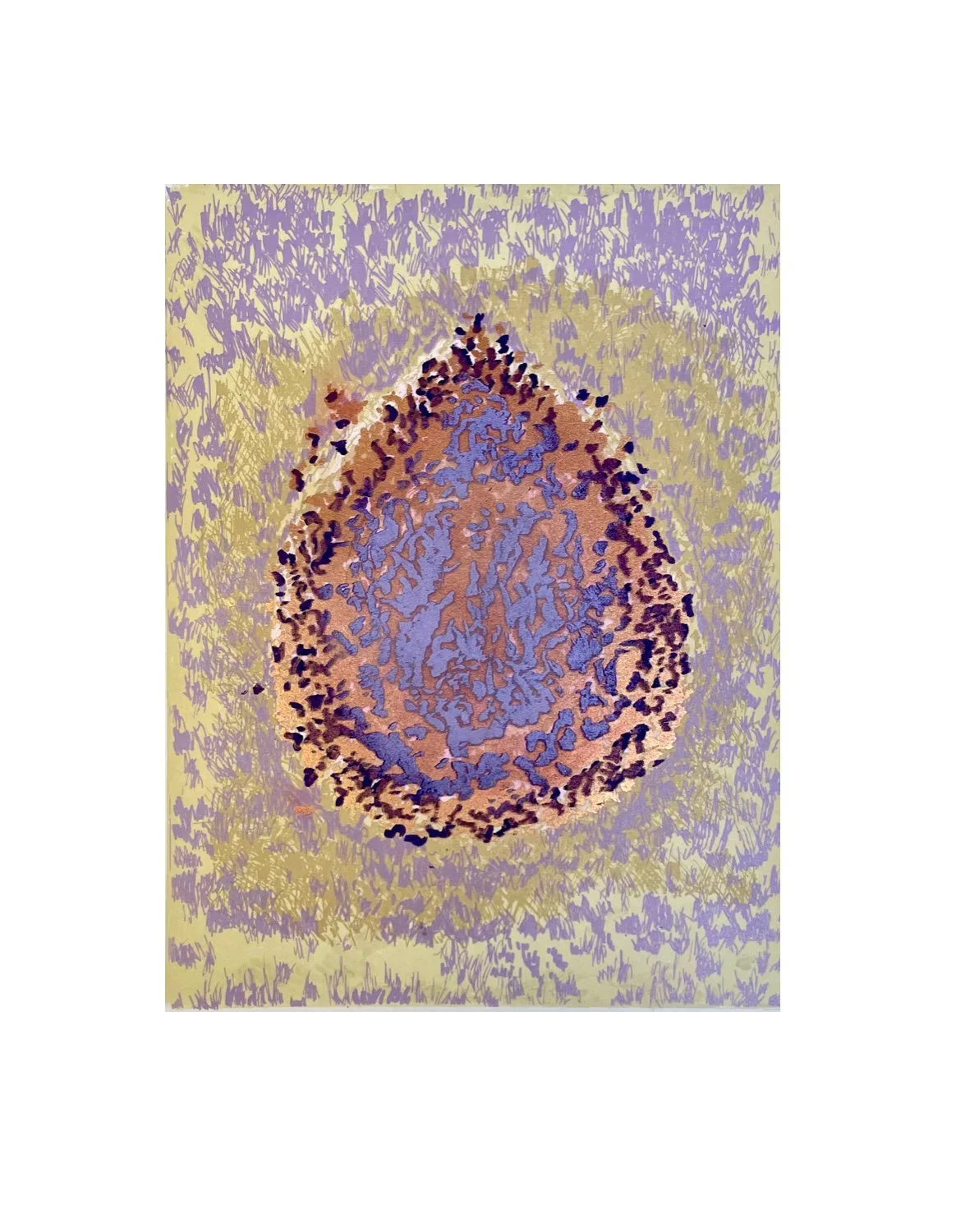

“Lavender Light,’’ by Phyllis Ewen, in her show “My Mind’s Eye,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, March 1-March 31. She lives in Somerville and Wellfleet, Mass.

She says:

“As Covid-19 continued and morphed, my art turned inward. A new series of lithographs reflected my changing state of mind and is continuing as is the pandemic. These lithographs come from MRI images of a brain.’’

“Guglielmo Marconi built the first transatlantic radio transmitter station on a bluff in South Wellfleet in 1901–1902. The first radio telegraph transmission from the United States to England was sent from this station on Jan. 18, 1903, a ceremonial telegram from President Theodore Roosevelt to King Edward VII. Most of the transmitter site is gone, however, as three quarters of the land it originally encompassed has been eroded into the sea. The South Wellfleet station's first call sign was "CC" for Cape Cod.’’

— Edited version of a Wikipedia entry

Not for book dropoffs

Outside the 1972 addition to the headquarters building of the Boston Public Library.

The front of the grand headquarters/main branch of the Boston Public Library, on Copley Square, one of America’s most beautiful public places. Designed by Charles McKim, the building was opened in 1895 as “a palace for the people.’’

(The editor of New England Diary, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

“Unhoused Bostonians continue to congregate around the main branch of the city library, a trend that’s unlikely to abate even if city housing investments start to pay off.

“Use of the sidewalk on Boylston Street beside the Boston Public Library (BPL) as a gathering spot for Boston’s homeless has produced some friction with passersby, mostly stemming from occasionally hazardous litter and some uncomfortable interactions with other library patrons.

“The BPL, city government and neighborhood groups have concentrated outreach efforts in the area, but it’s never gotten close to the level of obstruction and concern garnered at hotspots like Mass and Cass.’’

Back when it froze solid

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘When I was a kid we used to skate for several weeks each winter on a little pond in the woods near our house on the Massachusetts South Shore. It froze remarkably solid, especially considering that from time to time some salt water would get into it from a nearby marsh behind a beach.

We’d skate around in phases of euphoria and then sit by a fire we built along the shore, sometimes cooking hot dogs and marshmallows,. It’s surprising that we never ignited the thick stands of very dry-looking high sedge nearby. The boys would from time to time play chaotic games of hockey, using boots as goal markers.

In one of these games I fell on my right elbow, and was rewarded with a compound fracture. That in turn necessitated a hospital stay over the Christmas holidays of 1963 and some rather exotic procedures, presided over by a Dr. Mayo (!), whose first name is long lost to me.

Ah, the joys of morphine!

To hold my arm in the proper position for maximum healing, I had a cast around my chest for several months, with my arm stuck out as if I was about to shake hands. I still vividly recall the discomfort of taking tests with my left hand. And the itch under the cast…

I didn’t join in pond hockey games after that, though I went skating on the pond a few times, but its charms had faded for me.

Back in 2020, I lunched with a neighbor from those times, since deceased, who told me that no one skates on that pond anymore. The weather doesn’t stay cold enough, long enough anymore, he said.

Llewellyn King: Jimmy Carter haunts natural-gas decisions

Constellation’s Everett (Mass.) LNG Facility is the longest-operating liquefied natural gas (LNG) import facility of its kind in the United States.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The ghost of Jimmy Carter may be stalking energy policy in the White House and the Department of Energy.

In the Carter years, the struggle was for nuclear power. Today it is for natural gas and America’s booming liquefied-natural-gas future.

Decisions Carter took during his presidency are still felt today. Carter believed that nuclear energy was the resource of last resort. Although he didn’t overtly oppose it, he did damn it with faint praise. Carter, along with the environmental movement of the time, advocated for coal.

The first secretary of energy, James Schlesinger, a close friend of mine, struggled to keep nuclear alive. But he had to accept the reprocessing ban and the cancellation of the fast-breeder reactor program with a demonstration reactor in Clinch River, Tenn. Breeder reactors are a way of burning nuclear waste.

More importantly, Carter (ironically?), a nuclear engineer, believed that the reprocessing of nuclear fuel — then an established expectation — would lead to global proliferation. He thought that if we put a stop to reprocessing at home, it would curtail proliferation abroad. Reprocessing saves up to 97 percent of the uranium that hasn’t been burned up the first time, but the downside is that it frees bomb-grade plutonium.

Rather than chastening the world, Carter essentially broke the world monopoly on nuclear energy enjoyed, outside of the Soviet bloc, by the United States. Going forward, we weren’t seen as a reliable supplier.

Now the Biden administration is weighing a move that will curtail the growth in natural-gas exports, costing untold wealth to America and weakening its position as a stable, global supplier of liquified natural gas. It is a commodity in great demand in Europe and Asia, and pits the United States against Russia as a supplier.

What it won’t do is curtail so much as 1 cubic foot of gas consumption anywhere outside of the United States.

The argument against gas is that it is a fossil fuel, and fossil fuels contribute to global warming. But gas is the most benign of the fossil fuels, and it beats burning coal or oil hands down. Also, technology is on the way to capture the carbon in natural gas at the point of use.

But some environmentalists — duplicating the folly of environmentalism in the Carter administration — are out to frustrate the production, transport and export of LNG in the belief that this will help save the environment.

The issue that the White House and the DOE are debating is whether the department should permit a large, proposed LNG export terminal in Louisiana at Calcasieu Pass, known as CP2, and 16 other applications for LNG export terminals.

The recent history of U.S. natural gas and LNG has been one of industrial and scientific success: a very American story of can-do.

At a press conference in 1977, the then-deputy secretary of energy, Jack O’Leary, declared natural gas to be a depleted resource. He told a reporter not to ask about it anymore because it wasn’t in play.

Deregulation and technology, much of it developed by the U.S. government in conjunction with visionary George Mitchell and his company, Mitchell Energy, upended that. The drilling of horizontal wells using 3D seismic data, a new drill bit, and better fracking with an improved fracking liquid, changed everything. Add to that a better turbine, developed from aircraft engines, and a new age of gas abundance arrived.

Now the United States is the largest exporter of LNG, and it has become an important tool in U.S. diplomacy. It was American LNG that was rushed to Europe to replace Russian gas after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In conversations with European gas companies, I am told they look to the United States for market stability and reliability.

Globally gas is a replacement fuel for coal, sometimes oil, and it is essential for warming homes in Europe. There is no alternative.

The idea of curbing LNG exports, advanced by the left wing of the Democratic Party and their environmental allies, won’t keep greenhouse gases from the environment. It will simply hand the market to other producers such as Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

To take up arms against yourself, Carter-like, is a flawed strategy.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.