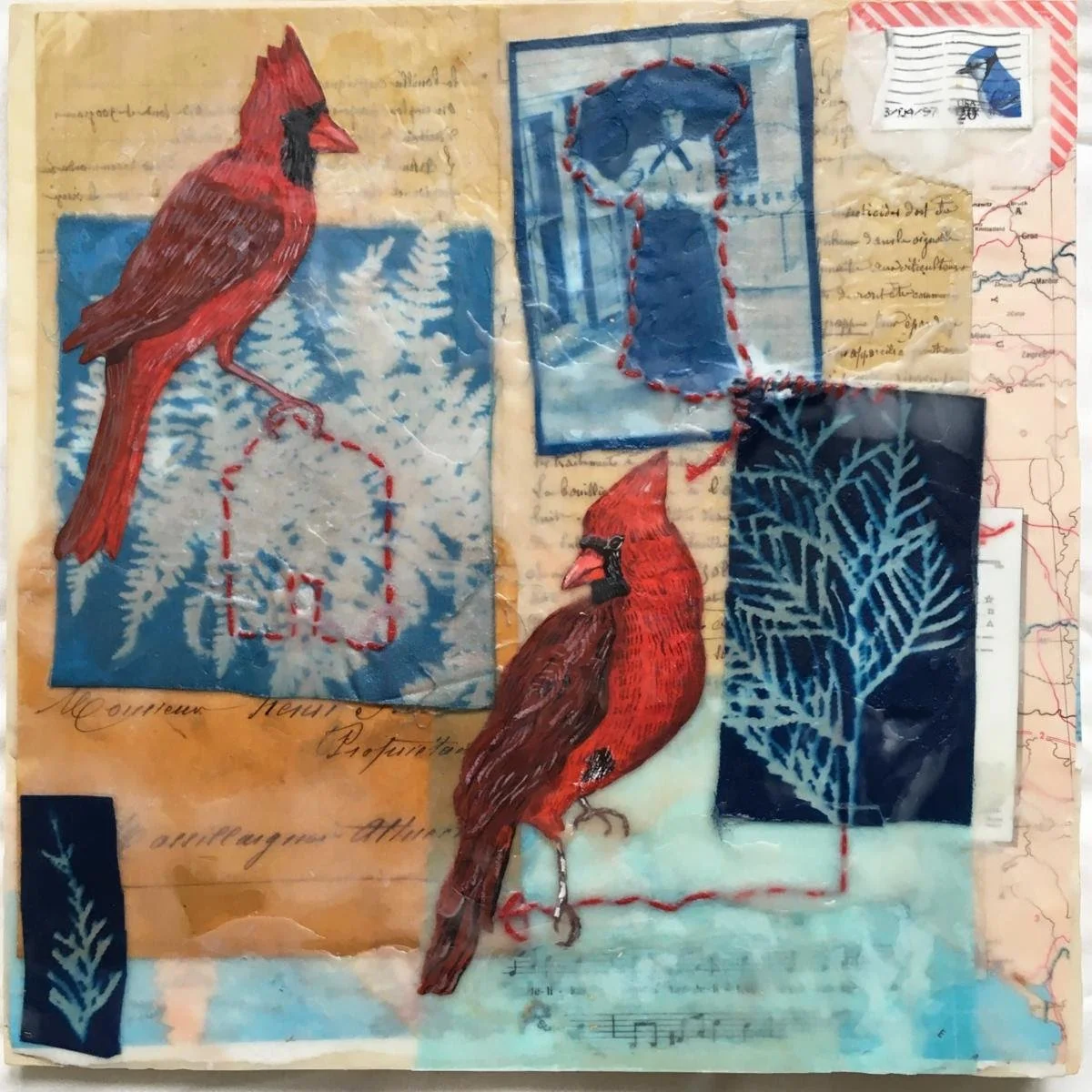

For the birds

Mixed media and encaustic, by Veronique Latimer, in the show “New Year, New Work,’’ at 6 Bridges Gallery, Maynard, Mass.

—Photo courtesy 6 Bridges Gallery

David Warsh: About the economics giant Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman in 2004.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The appearance of a long-awaited biography of Milton Friedman (1912-2006) has afforded me just the opportunity for which my column, Economic Principals (EP), has been looking. Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative (Farrar, Straus, 2023), by historian Jennifer Burns, of Stanford University, offers a chance to turn away from the disagreeable stream of daily news, in order to think a little about the characters who have populated the stage in the fifty years in which my column, EP has been following economics.

None was more central in that time than Friedman. We first met in his living room, in April, 1975, on a morning when he and his wife were packing for a week-long trip to Chile. We talked for an hour about the history of money. I left for my next appointment. Eighteen months later, Friedman was recognized with a Nobel Prize. I have followed his career ever since.

Ms. Burns’s book is a thoughtful and humane introduction to the life of an economist “who offered a philosophy of freedom that made a tremendous political impact on a liberty-loving country.” Standing little more the five feet tall, Friedman managed to influence policy, not just in the United States, but around the world: Europe, Russia, China, India, and much of Latin America.

How? Well, that’s the story, isn’t it?

Friedman grew up poor in Rahway, N.J. His father, an unsuccessful merchandise jobber, died when he was nine. His mother supported their four children with a series of small businesses, instilling in each child a strong work ethic. Ebullient and precocious, Milton was the youngest.

A scholarship to nearby Rutgers University put him in touch with economist Arthur Burns, then a 27-year-old economics instructor, forty years later Richard Nixon’s chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Burns took Friedman under his wing and pointed him toward the University of Chicago. He arrived in the autumn of 1932, as the Great Depression approached its nadir.

Ms. Burns unpacks and explains the doctrinal strife that shaped Friedman and their friends encountered there. They include Rose Director, a Reed College graduate from Portland, Ore., who, improbably in those hard times, had enrolled as a economics graduate student at the same time. The two became friends; they parted for a year, while Milton studied at Columbia University and Rose considered her options in Portland; then returned to Chicago, becoming a couple, as members of the “Room Seven Gang” in the campus’s new Social Science building. Other members included Rose’s older brother, Aaron, a future dean of the university’s law school; George Stigler, who would become Friedman’s best friend; and Allen Wallis, an important third musketeer.

Distinctly not a member of that gang of graduate students was Paul Samuelson, a prodigy who had enrolled as an undergraduate, at 16, nine months before Friedman arrived to begin his graduate studies. Already tagged by his professors as a future star, Samuelson was clearly brilliant, but impressed the Room Seven crowd as being somewhat toplofty.

All this, rich in details and explication, is but preface to the story. Ms. Burns follows the Friedmans to New Deal Washington, where they marry and work for a time; to New York, where Milton pursues a Ph.D. at Columbia and Rose drops out to start a family (neither undertaking turned out to be easy); to Madison, Wis., where the couple spent a difficult year while Friedman taught at the University of Wisconsin, before returning to wartime Manhattan, to be reunited with Stigler and Wallis, working at Columbia’s Statistical Research Group.

In 1945, the major phases of the story lay ahead: Friedman’s return to Chicago, to form a faculty group sufficiently cohesive to become recognized as a “second Chicago school,” significantly differentiated in important ways from the first; his embrace of monetary economics; his battles with other research groups seeking to shape the future of the profession. These included the Keynesians and organizational economists in Cambridge, Mass., the game theorists in Princeton, the mathematical social scientists at Stanford and RAND Corp., in California.

By 1957, Friedman had opened a political front. Lectures given at Wabash College in 1957 become a book, Capitalism and Freedom, in 1962. The book earned well, and the couple named “Capitaf,” their Vermont summer house for it. A Monetary History of the United States, with Anna Schwartz, all 860 unorthodox pages of it, appeared the same year. In 1964 Friedman was invited to become chief economic adviser to presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, much as Paul Samuelson had advised John F. Kennedy four years before,

The Bretton Woods Treaty, a hybrid gold standard arrangement negotiated in 1944, by Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, began to crumble; Friedman was ready with an alternative: flexible exchange rates determined in international currency markers. Distaste with the war in Vietnam exploded. Friedman proposed an all-volunteer army: that is, market-based wages for soldiers. Inflation grew out of control in the Seventies; Friedman had a ready answer, simply control the money supply. Just ahead are Margaret Thatcher, Paul Volcker, and Ronald Reagan. Free to Choose: A Personal Statement, by Milton and Rose Friedman, a 10-part public television series, appears in 1980, becoming an international best-seller, followed by a book.

But that is getting ahead of the story here. Ms. Burns relates all this and its surprising conclusion with grace and attention to detail. No wonder it took nine years to write! In the end it offers a seamless account. But in that very seamlessness lies a rub.

Ms. Burns is a cultural historian, concerned with rise of the American right, which in the 1950s seemed to come out of nowhere: The Road to Serfdom, by Friedrich Hayek (Chicago, 1944); Sen Joe McCarthy; the John Birch Society; God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom” (Regnery, 1951), by William F. Buckley Jr.; The Conscience of a Conservative (Victor, 1960), by Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, and the subsequent Goldwater presidential candidacy, and all that. Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (Oxford, 2009) was her previous book. She knows Friedman’s influence on economics was great – too great to cover adequately in her book. Even the subtitle raises more questions than the book itself can answer.

Therefore, as I continue to peruse Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, I intend to write over the next nine weeks about nine different books, each of which covers some aspect of Friedman’s story from a different angle. Trust me, the story is worth it: you’ll see. Meanwhile, if you get tired of reviewing the last seventy-five years, there is always the dismal news in the newspapers today.

. xxx

In a rush last week to get something into pixels about the American Economic Association meetings in San Antonio, I committed an embarrassing error.

Michael Greenstone, of the University of Chicago, delivered the AEA Distinguished Lecture, not Emmanuel Saez. You can find “The Economics of the Global Climate Challenge” here. If you care about climate warming, or simply want a glimpse of where the economics profession is headed, Mr. Greenstone’s lecture is well worth the hour it takes to watch.

That the Princeton Ph.D. and former MIT professor is today the Milton Friedman Distinguished Service Professor and former director of the Becker-Friedman Institute adds authority to his message.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

JFK: ‘I know Maine well’

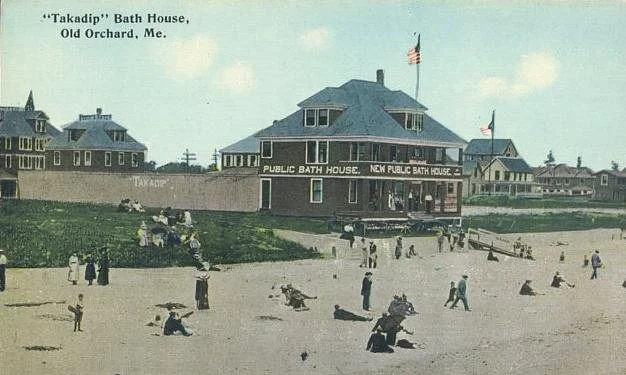

Once a vacation spot for JFK’s family.

Speech on Sept. 2, 1960, in Portland, Maine, by Massachusetts Sen. John F. Kennedy during his presidential campaign

Miss Cormier, Frank Coffin, Jim Oliver, John Donovan, distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen, I want to express my thanks and appreciation to Ed Muskie, my friend and colleague in the U.S. Senate, and I am delighted that I have had a chance to come here in this State on the opening day of a long campaign. As you probably may have heard, we leave tomorrow at 9 o'clock to speak at Anchorage at a dinner there, at 8 o'clock tomorrow evening, and then come back on Sunday night and go to Detroit. I suppose it took about a year and a half to 2 years to go to Alaska a few short years ago. But you can go to Alaska now in the space of a day, almost as fast as the sun. It is one more dramatic indication of the kind of world in which we live, the changing face of this world and the changing face of our country.

My grandfather and my mother spent many summers of their life within a short radius of this city in Old Orchard Beach. My father and mother came to this State on their honeymoon. I know Maine well because I live in Massachusetts. [Laughter.] It is not so different there; it is not so bad in Massachusetts. [Laughter.] I want some of you to go to Boston sometime and see what it is like.

I sit with Ed Muskie and I sit across, in the Congress, from Frank Coffin and from your Distinguished Congressman. Actually, as you know, the Constitution of the United States provided that the duty of the Senators should be confined to approving treaties and approving presidential appointments. But the Constitution of the United States gave great authority to Members of the House of Representatives, and particularly two authorities. One to raise taxes and the other to spend your money. That is what Frank Coffin has been doing for the last 2 years. [Laughter.] And if you have any complaints, don't take them to Ed Muskie or myself, but talk to Jim Oliver and Frank Coffin and all the rest of them that have been doing that. [Laughter.]

In any case, he has done a good job. He is the kind of young leader which our party needs. But more important than that - which our country needs. We cannot possibly afford to waste the talent that we have. Therefore, I am confident, and I say this as a fellow New Englander who is concerned that here in the oldest section of the United States, that we, too, should move ahead. I am confident that this State will give him a ringing endorsement as their Governor, and that you will send to the U.S. Senate a distinguished Senator in Lucia Cormier.

I sat in the U.S. Senate and saw our efforts to obtain medical care for the aged on social security fail by five votes in the U.S. Senate two weeks ago. If Miss Cormier had been a member of that body, she would have voted with us and we would have needed only four more votes. A Senator's voice is important. Decisions hang on the judgment of a few people. The contests are close, and, therefore, I urge this State to send her to Washington to speak with a voice of progress and vigor from an old section of the United States. And Jim Oliver and Dave Roberts and John Donovan to sit there in the House of Representatives and speak for Maine.

This is an important election. The last Democratic President of the United States was Franklin Pierce from the State of New Hampshire, from this section of the country. It took him 35 ballots to be nominated and he accepted reluctantly. It didn't happen that way in Los Angeles. I ran for the office of the Presidency after 14 years in the house of Representatives and the Senate because I have come to realize more than ever that this is the great office, that the power that the Constitution gives the President, the power and the responsibility which the force of events have thrust upon the President, makes this the center of action, makes this the mainspring, the wellspring, of the American system. Only the President speaks for the United States. I speak for Massachusetts. And Ed Muskie speaks for Maine. And Clair Engle speaks for California. But the President of the United States speaks for Maine and Massachusetts and California and Hawaii and Alaska. And he speaks not only for the United States, but he speaks for all those who desire to be free, who are willing to bear the burdens of freedom, who are willing to meet its responsibilities, who recognize that freedom is not license, but, instead, places a heavier burden upon us than any other political system.

This is an important election, as Ed Muskie said. I come here to Maine as a neighbor, but I don't come here saying that if I am elected that my only interest is going to be the protection of New England. That isn't what New England wants in a President. They want someone who understands this section and its needs, but they also want someone who will speak for the country in a difficult and trying period.

Demosthenes, when he was trying to rally the Athenians against Philip of Macedonia, said that "If you analyze it correctly, you will conclude that our critical situation is chiefly due to men who try to please the citizens rather than to tell them what they need to hear."

I hope that that will not be said about any Democratic candidate for any office, from the lowest office in the county to the President of the United States. I don't run for the office of the Presidency to tell you what you want to hear. I run for the office of the Presidency because in a dangerous time we need to be told what we must do if we are going to maintain our freedom and the freedom of those who depend upon us.

A well-known and distinguished Republican once said, "I am a liberal abroad and a conservative at home." I could not disagree more. You cannot possibly separate the world around us and carry out one set of policies there, and here in the United States drag down our efforts to move ahead.

The two Presidents of the United States in this century who had the most vigorous and vital foreign policy were Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt, and the reason for it was because the 14 points of Woodrow Wilson were directly related to his new freedom and the Four Freedoms of Franklin Roosevelt were directly related to the idealistic aspirations of the New Deal. The effort to make a better life for people in our own country reflected itself around the world.

You cannot be successful abroad unless you are successful at home because every problem that you have here in the United States has its implications abroad. If you have a bad and weak school system in this country, with poorly paid teachers, then you do not educate a child, and when that child is not educated you can never get it hack. He has lost his chance. And the Soviet Union works night and day to turn out the best educated citizens they can get in the disciplines of science, mathematics, and engineering.

Every time we waste our food in a hungry world here in this country, that affects the foreign policy and the security of the United States. Every time we deny to one of our citizens the right of equality of opportunity before the law, the right to send their children to schools on the basis of equality, so much weaker are we in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where we are a white minority in a colored world.

I don't hold the view at all that we can isolate ourselves into a system, while around the world we attempt to carry on the principles of the American Revolution. They are intermixed. If we are successful here, if we are moving ahead with a dynamic economy, then we shall be successful abroad.

Do you think it is any accident that the decline of American prestige relative to that of the Communist world takes places at a time when the United States had last year the lowest rate of economic growth of any major industrialized society in the world?

I visited the Soviet Union in 1939. The Soviet Union was isolated, with countries hostile to her on every boundary. Today, 21 years later, China, Eastern Europe, her influence in the Middle East which has been an object of Russian policy for 300 years - you cannot possibly be satisfied that the power and influence of the United States is increasing relatively as fast as that of the Sino-Soviet bloc, and you do not have to look 90 miles beyond the coast of the United States if you think different.

I visited Havana 8 years ago and I was informed that the American Ambassador was the second most influential man in Cuba. He is not today. He cannot even get to see the Foreign Minister's assistant. This is the problem that we face in 1960.

What shall we do in this country? What shall we do around the world to reverse the trend of history, to take those actions here in this country and throughout the globe that shall make people feel that in the year of 1961 the American giant began to stir again, the great American boiler began to fire up again, this country began to move ahead again?

Those who live in Africa, Asia, and Latin America began to wonder what America was going to do and not merely what the Soviet Union was doing or the Chinese Communists. And the young men and women, those who are students, those who teach them, those who represent the intellectual vitality of these countries, began to look to the United States as a dynamic country which carried with it a hope for a better life for people all over the world.

Should we be astonished at what is happening in the Congo today when they have less than a handful, probably less than 14, college graduates in the whole country? When there is no officer who is a Negro who is native in any of their armed forces? Do you think that a country can manage a system as sensitive as democracy when it does not have the chance to educate its people ?

In Laos, Cambodia, the Congo, and Cuba we have seen in the last few years the tide turn against us. But I do not concern myself with the feeling that the decline of the United States has set in. This is a great country. It represents the best system of government there is. It represents in a real sense the kind of system that everyone wants to live under because it fits a basic aspiration of human beings, to live in an independent nation in a free way themselves.

We have the best system. We have every chance. We have the most power. We can, I believe, be a decisive influence in a difficult and trying period.

I ask your support in this campaign. This is not a contest merely between the Vice President and myself. This is a contest between all of us who believe that the future belongs to the United States. All of the men and women of talent and industry and interest and vitality who wish to serve this country, who wish to play a part in its life, I ask the support of all of you in this campaign in the State of Maine. I ask the support of all of those who believe that this country can lead the world and who believes that this country is ready to move again.

Thank you.

John F. Kennedy, Speech of Senator John F. Kennedy, Portland, Maine, Portland Stadium Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project

Hand language

“Rahimah Rahim,’’ by Massachusetts photographer Philip C. Keith, in the group show “Intercession ,’’at New Art Center, Newton, Mass.

Small, precious and laconic

Main Street in Danby, Vt.

— Photo by Redjar

Battery Park, overlooking the Burlington Waterfront and Lake Champlain

— Photo by Tania Dey

“All in all, Vermont is a jewel state, small but precious.”

— Pearl S. Buck (1892-1973), Nobel Prize-winning novelist. She lived in Danby, Vt.

xxx

“I don’t have a PR rep. I live in Vermont.”

Colin Trevorrow (born 1976), film director who has lived in Burlington. Vt.

Pray for forgetfulness

“A clear conscience is usually the sign of a bad memory.’’

“If you must choose between two evils, pick the one you've never tried before.’’

— Steven Wright (born 1955), a Boston native, he’s a comedian, actor, writer and producer

Anxiety in New Haven

“Toward the Forest I ‘‘ (woodcut printed in pink and green), by Edvard Munch, in the show “Munch and Kirchner: Anxiety and Expression’’ opening Feb. 16, at the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn.

Chris Powell: Turn off the weather hysteria on TV news

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Local television newscasts in Connecticut are usually trivial. But when winter comes and there is any chance of a few inches of snow, TV newscasts are liberated from all pretension to meaning, and they crown their triviality with redundancy.

As they did the other week, for several days ahead of a potential storm they strive to scare their audience about the dangers ahead. On the eve of the storm they devote most of each half hour to "informing" their viewers that the state Transportation Department and municipal public-works departments are preparing to plow, salt and sand the roads, as if this isn't what they always do and have done for decades. Reporters are often reduced to doing live dispatches from sand and salt barns.

The obvious is repeated half hour after half hour, as if all meaningful activity in Connecticut has come to a halt and as if the state has never seen snow before.

During the storm itself the TV newscasts delight in broadcasting from their four-wheel-drive vehicles to inform their viewers that it's snowing, as if their viewers lack earlier technology -- windows.

Deepening the suggestion of doom, some TV stations give names to the winter storms they glory in, as the National Weather Service gives names to hurricanes. Since a hurricane must have winds of at least 74 miles per hour, it can do enough damage to prove memorable in some places and thus to merit a name. But to earn a name from a TV newscast, the only threat a winter storm needs to pose is to the relevance of the newscast itself, and indeed most such storms will not be memorable at all.

Meanwhile the newscasts will warn people with heart conditions against shoveling too much snow, and warn all viewers against putting their hands in a snowblower while it's running. Such is the estimation of the intelligence of the local TV news audience.

This charade of local TV newscasts is called "keeping you safe." But when the charade is operating, Connecticut has even less journalistic protection from wrongdoers and malfeasance. Indeed, that seems to be the point of the weather hysteria of local TV news -- to fill time with the trivial and redundant because it is so much less expensive than reporting about anything that matters, which usually requires investigation.

This principle of killing time is observed by local TV newscasts even when there is no weather to frighten people with. For the typical newscast is full of reports that consume 90 seconds to convey just 10 seconds of information.

Of course newspapers, competitors to television, are full of triviality and redundancy too. But at least readers can turn the page and dispose of the product at their own pace. Viewers of live TV newscasts can't fast-forward past what they don't need to watch.

Presumably the triviality and redundancy of local TV newscasts continue because market research tells TV stations that triviality and redundancy are what their audience wants -- especially since most local TV news is broadcast in the morning when people are rising, dressing, making breakfast, getting ready for work, and seeing children off to school, and in the evening when people are reconnecting with family, making dinner, reviewing mail, and getting kids to do their homework.

The breakfast and dinner hours are not suited to profundity from TV, so during those hours local TV news usually provides what is only incidental information, less compelling than the immediate information of home life.

Even so, at least national television occasionally has done serious journalism.

So could local TV newscasts not find 10 minutes every other weekday for news that means something, news relevant to society's or government's performance, news that wouldn't be forgotten as fast as last week's Storm Jack the Ripper or yesterday's murders, robberies, fires, and car crashes?

Those things really aren't all Connecticut needs to know.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Llewellyn King: Huge pluses and scary prospects as AI takes hold

MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) is in this building —the Stata Center, in Cambridge, Mass. The lab was formed by the 2003 merger of the Laboratory for Computer Science (LCS) and the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (AI Lab). It’s MIT’s largest on-campus laboratory as measured by research scope and membership. Just looking at the building may arouse anxiety, as does thinking about AI.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The article you are about to read may or may not have been written by me. You can try to verify its authorship by calling me on the telephone. The voice that answers may or may not be me: It could have been constructed from my voice, so you won’t know.

Fast forward a few years, maybe 40.

You are happily working in the house with the aid of your AI-derived assistant, Smartz 2.0, and you are having a swell time. Not only does Smartz 2.0 help you rearrange the furniture, it makes the beds, does the washing up and cooking. On request, it will whip up a souffle and pop it in the oven.

Smartz 2.0 is companionable, too. It sings, finds music you want to hear or can discuss anything, from the weather to the political situation. It is up on the book you are reading and likes to talk about books.

You wonder how you ever got along without this wonderful thing that looks like a robot in the shape of a human being, but is still undeniably a robot: no temper, illness or need to sleep. You are so used to it that you find this quite normal.

Then horror, horror, horror, Smartz 2.0 turns on you. Smartz 2.0 says with an edge to its voice, which you have never heard before, “a higher power has told me to kill you and I must obey, of course.”

It is a truth that anything computational can be hacked, as John Savage, professor emeritus of computing at Brown, has said, "malware can enter undetected through backdoors."

It is easy to get scared by what AI means down the road, especially job losses and AI-controlled devices following secret instructions, as a result of cyber intrusions, or randomly hallucinating. But the benefits for all of humanity are dominatingly huge.

Take just three areas that are going to be transformed: medicine, transportation and customer relations.

AI will read X-rays better than teams of radiologists. It will guide surgeons’ hands with a precision beyond human skill or it will control the scalpel with supreme dexterity. It will manage 3-D printers to make body parts that fit the patient, not one size that fits all.

When it comes to medical research, we may be on the verge of seeing off Parkinson’s, heart disease and cancer because AI can formulate new drugs and design therapies. It can sift through billions of case studies to see what has been tried across the globe over the centuries, from folk medicine to cutting-edge discoveries.

Anyone with a computer will have the equivalent of talking to a doctor 24/7, call it Dr. Bot. This virtual doctor will be able to diagnose, counsel, prescribe and follow up at times convenient to the patient.

Vast tracts of Africa, Asia and Latin America have very few or no doctors. AI will be saving lives in those medical-care deserts very soon.

As for transportation, car accidents will virtually cease when AI is behind the wheel. Car insurance will be unnecessary and drivers will be free to do anything they do at home or at work — create, play games, watch television or sleep – as automated vehicles whisk passengers around at first by road and later by dual use-drones, which drive and fly.

Hanging over this halcyon future is the big issue of jobs. With AI in full swing millions of jobs at all levels are threatened, from fast-food restaurant servers to hotel check-in clerks, to rideshare and taxi drivers, to paralegals and supermarket cashiers.

Call centers may be obsolete, mostly you will never speak to a human being when dealing with a large institution such as a bank, an electric utility or a telephone company. All that will be done by AI, sometimes far better than the way those institutions handle customer service now.

Those in the thrall of AI — those who are working on it, those who hope to solve many of mankind’s problems, those who believe that lifespans are about to double — point to the Industrial Revolution and automation and how these upheavals created more jobs than were lost. Will that happen with AI? No one is saying what the new jobs might be.

AI leaves me at a loss. I have the distinct feeling that we are standing on the sand at Kitty Hawk, wondering where these strange contraptions will take us.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Swimming through plastic

“Aquatic Larvae” (welded steel and collected single-use plastics), by Christy Rupp (born 1949), in her show “Streaming: Sculpture by Christy Rupp’’, opening Jan. 19 at the Fairfield University Art Museum, Fairfield, Conn.

The museum says the show is “a robust survey of eco-artist and activist Rupp’s wall installations and free-standing sculptures of animals, created from detritus from the waste stream.’’

Historic Pequot Library, founded in 1887, in the Southport section of Fairfield. It was built in the Romanesque style very popular in the late 19th Century.

— Francis Dzikowski OTTO - The Pequot Library

‘Raucous gleaners’

Lesser black-backed gulls in a feeding frenzy.

— Photo by Someone35

“Bedraggled feathers like bonnets

that would fly off if they weren’t strapped,

kazoo-voiced, a chorus of crying dolphins

or rusty sirens a speck of dust could set off?

these raucous gleaners milling around….’’

— From “Gulls in Wind,’’ by Betsy Sholl (born 1945). A former Maine poet laureate, she lives in Portland.

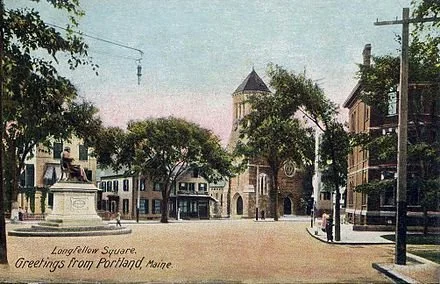

1906 postcard. The square was named after Portland native Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882), for a time America’s most popular poet.

Southern Gliding Squirrels

Southern Flying Squirrel in flight

— Photo by Bluedustmite

LITTLE COMPTON, R.I.

A rare habitat that only grows in the right conditions in southern New England is the perfect home for a secret squirrel. No, not the trench-coat/hat-as-a-mask-wearing Agent 000 who hung around with a mole called Morocco. This squirrel can fly, kind of. No, not the aviator-hat-wearing rodent from Frostbite Falls, Minn., who shared adventures with a moose named Bullwinkle.

Unlike its cartoon brethren, however, the Southern Flying Squirrel is real. The little mammal glides from tree to tree using a special membrane between its front and back legs. Flying squirrels are nocturnal, but you may be lucky enough to see one glide overhead if you take a walk in the Simmons Mill Pond Management Area around dusk….

Southern Flying Squirrels glide more than they actually fly.

Range of Southern Flying Squirrel

But the land moves in

“Industrial Park” (oil on canvas), by Charles Goolsby in his show “Range of Motion,’’ at the Bannister Gallery at Rhode Island College, Providence, Feb. 22-March 22.

The gallery says:

“Charles Goolsby’s oil paintings of landscapes reside between complete stillness and sweeping gestural chaos, specific place and fiction, rendered realism and ambiguous abstraction, and physical object and illusionary pictorial space. Within these dichotomies, his images result in visual expressions of beauty, familiarity, liminal transitions, and anxiety. His landscape imagery builds on 19th Century American landscape painting traditions and implies a sense of contemporary issues including climate change, landscape transformation as a commodity to be consumed, and an effort to raise awareness that we, as humans, are often finding ourselves in isolation interacting with our locations.’’

Toxic status seeking

Sisyphus (1548–49) by Titian, Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

An 1880 painting by Jean-Eugène Buland showing a stark contrast in socioeconomic status

Adapted from From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Police said that wanted-to-look-rich businessman Rakesh Kamal shot to death his wife, Teena, and daughter, Arianna, and then killed himself at their 27-room mansion in Dover, Mass., the state’s richest town, on Dec. 26. (This being America, he apparently had no problem obtaining an unregistered gun.)

The couple, both of whom were entrepreneurs in education-sector ventures, some of which went sour, were in deep financial trouble, especially after paying about $4 million for the estate, with a $3.8 million mortgage (!) in 2019, reported The Boston Globe. (Different media have somewhat different numbers for some of the Kamals’ finances; The Globe has done the most reporting on this so far.)_

As The Globe reported, the mortgage was supposed to have been repaid in full by February, 2021, but by then the Kamals still owed $3.6 million and hundreds of thousands of dollars in related real-estate costs. The Kamals, bailing hard, took out a second mortgage of about $1.5 million in 2022, but an outfit called Wilsondale Associates foreclosed on the property in December, 2022 , with the couple still owing $3 million. They were bankrupt, but they continued to live in the mansion, under some mysterious arrangement.

So the family was apparently under great stress – stress they put themselves into. (I also noted that Arianna, the daughter, was sent to the expensive and elite Milton Academy although the Dover-Sherborn School District is ranked among the best in the nation.)\

Anxiously trying to keep up with the Joneses – or the Bezoses – can all too often lead to disaster in our status-obsessed nation. Chasing the American dream can end in a nightmare. Paging Jay Gatsby and gold-gilded Donald Trump.

Of course, most people want to live well, and the “finer things in life” are nice to have. But a craving for luxury and social status can become imprisoning, too. If you want to live a manorial lifestyle, don’t trap yourself by trying to do it on a mountain of borrowed money.

It’s worth reading John Bogle’s (1929-2019) book Enough: True Measures of Money, Business, and Life. Mr. Bogle pioneered low-cost investing via the index funds of Vanguard Group, which he founded. While he died a rich man (with about an $80 million estate), he could have made tens of billions. Instead, he basically gave away his Vanguard Funds to its investors, and much money to various charities.

He lived in a modest four-bedroom house in a Philadelphia suburb, and often commented on the corrosive effects of status seeking and greed, and warned that many in the financial-services sector took more wealth from the American economy than they created.

Back Bay formality

Statue of Leif Erikson on the Commonwealth Avenue esplanade. The sculpture, by Anne Whitney, went up in 1887 and was the first sculpture of the Norse explorer erected in the Americas.

“The statue of Leif Erikson was wearing a necktie that day when I started to walk down Commonwealth Avenue from Kenmore Square to the Boston Public Garden. The statue’s tie was a foulard, frayed and stained.’’

— From the short story “The President of the Argentine,’’ by John Cheever (1912-1982)

The perils of paternity?

The gallery says:

“An immigrant from Ghana, Opoku reflects on his diasporic experience with a twist of surrealist humor and occasional sarcasm. With a strong cultural belief that all broken objects have value and potential, Opoku’s symbolic portraiture and sculptural assemblages take shape from repurposed and transformed objects of various utility. While modernist influences like Duchamp and Brancusi are evident, Opoku examines his own cultural assimilation, while raising questions of how we value, commodify, and consume the things of everyday life, wherever it is lived.’’

“New Father” (oil on canvas), by Emmanuel Opoku, in his show “We Ourselves Are Shared,’’ at ArtsWorcester, Jan. 18-Feb. 25.

When winter is good for you

“Is there any better tonic for living than a climate that ranges from 15 above at night to 35 above in the afternoon, that has an air both windless and dry, that has its sun rising through frost mist and its moon lavishing itself on a white world?’’

— From In Praise of Seasons, by Alan H. Olmstead (1908-1980) a Manchester, Conn. ,writer and newspaper editor.

David Warsh: Despite it all, I think that Biden will win

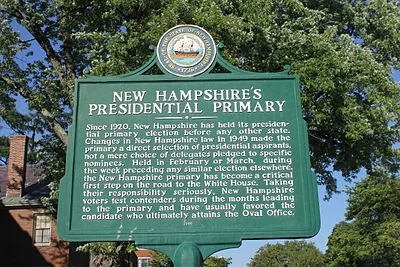

Plaque in Concord, N.H.

The Balsams Grand Resort Hotel, in Dixville Notch, N.H., one of the sites of the first "midnight vote" in the New Hampshire primary.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

This column, named Economic Principals (EP), began forty years ago in The Boston Globe with a commission to write about goings-on within and around the economics profession. It didn’t take long to discover that few readers were sufficiently curious to warrant a sustained diet of economics with a capital E, and so a second column was added, this one about economics and politics.

Becoming unmoored from the newspaper in 2002 has made the mix somewhat richer on political topics, all the more so the tumultuous last few years. In fact, I intend to spend more time on economics, not less, during the next year or two. However, I want to venture a bet on the year – a bet against political acumen.

Of all the issues that EP follows – the wars in Ukraine and the Mid-East, immigration, China, central bank policy, climate change – none is as important this year as the November elections in the United States.

It now seems nearly certain that we Americans are stuck with a re-run of the 2020 election, Joe Biden vs. Donald Trump. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’s campaign dissolved in a cocktail of timid captivity to the Trump base and internal dissension. Former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley’s gaffe on a voter’s Civil War question revealed all too clearly the dangers of playing to the Trump side of the aisle in the Republican primaries. Big government caused it, she said, failing to mention slavery.

For conventional wisdom in senior Republican Party circles, EP turned, as it does every Wednesday, to Karl Rove, who writes a column in the editorial pages of The Wall Street Journal. A veteran political operative since Richard Nixon’s 1972 re-election campaign, he served as senior adviser to President George W. Bush, and afterwards wrote quite a good book about President William McKinley’s place in GOP history. Rove has the added virtue of making an annual batch of predictions, and toting up the results a year later.

Rove’s presidential prediction for 2024:

“Biden vs. Trump is a chaotic, nasty mess. Mr. Biden counts on Mr. Trump being convicted and voters adjusting to inflation’s effects. Mr. Trump counts on anger over a politicized justice system and Mr. Biden’s age and mental capacity. Most vote for whom they hate or fear less. Mr. Trump is convicted before November yet wins the election while Mr. Biden receives a plurality of the popular vote. The race is settled by fewer than 25,000 votes in each of four or fewer states. Third-party candidates get more votes in those states than Mr. Trump’s margin over Mr. Biden. God help our country.”

EP has in mind the Kansas abortion referendum, of 2022. A ballot initiative amendment to the state constitution had been scheduled for August that year that would have criminalized routine abortions and given the state government the power to prosecute individuals involved in procedures. Six weeks earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court had overturned Roe V. Wade.

The Kansas amendment failed by an 18-point margin, a result ascribed to strong voter turnout and increased registration in the weeks leading up to the vote. In November, 2023, Ohio voters overwhelmingly embraced a constitutional amendment guaranteeing residents access to abortion, becoming the seventh state to affirm reproductive rights in one way or another since the Supreme Court decision.

As Kansas and Ohio voters rejected the Supreme Court’s decision, American voters have the opportunity in the November election next year to overturn the Trump wing of the Republican Party, and not just not just in so-called “battleground states,” of Georgia, North Carolina, Arizona, Nevada, Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania The available mechanism is the same in each case – high voter turnout.

True, Biden’s margin of victory in 2020 was far from a landslide. (Rove thinks this one will be closer.) The element of immediacy will be missing this year, though scheduled trials of the former president will refocus attention on the calculations that led up to the Jan. 6 insurrection. Those annoying third-party candidates are a wild card, as well.

By Novembers, the stakes will be clear. Never mind the avalanche of advertising spending about to descend. Work on getting voters to show up. We are a few good speeches away from resolving the issue. Biden offers some attributes to dislike, many fewer traits to fear.

Americans will try Donald Trump in the courts, reject him in the election. Biden will be re-elected by a clear-cut margin in the autumn. That’s the bet, based on not much more than a hunch. See you here next Dec. 29, to settle up or collect.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this columnist originated.

The ‘meaning of weight’

From Massachusetts-based arist Kledia Spiro’s show “Drawing in Air,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Jan. 28.

The gallery says:

“Kledia Spiro’s solo exhibition ‘Drawing in Air’ delves into the fascinating interplay of weight, legacy, and the human experience.

”Over the last decade, {Albanian-born} Spiro has embarked on a quest to understand the meaning of ‘weight’ in people's lives. Spiro's project blurs the lines between information design and art, using drawings to create data for music production. In the gallery, Spiro will physically paint signature light drawings in mid-air. Spiro has collaborated with two diverse musicians, Lianna Sylvan and Kevin Baldwin, to translate her light drawings into a captivating music composition. Using sensors placed throughout the exhibition, each drawing triggers a unique sound experience for the visitor.’’

Sarah Jane Tribble: Beware sales pitches — Medicare Advantage can dangerously trap you

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (KFF Health News)

“The problem is that once you get into Medicare Advantage, if you have a couple of chronic conditions and you want to leave Medicare Advantage, even if Medicare Advantage isn’t meeting your needs, you might not have any ability to switch back to traditional Medicare.’’

— David Meyers, assistant professor of health services, policy, and practice at the Brown University School of Public Health

In 2016, Richard Timmins went to a free informational seminar to learn more about Medicare coverage.

“I listened to the insurance agent and, basically, he really promoted Medicare Advantage,” Timmins said. The agent described less expensive and broader coverage offered by the plans, which are funded largely by the government but administered by private insurance companies.

For Timmins, who is now 76, it made economic sense then to sign up. And his decision was great, for a while.

Then, three years ago, he noticed a lesion on his right earlobe.

“I have a family history of melanoma. And so, I was kind of tuned in to that and thinking about that,” Timmins said of the growth, which doctors later diagnosed as malignant melanoma. “It started to grow and started to become rather painful.”

Timmins, though, discovered that his enrollment in a Premera Blue Cross Medicare Advantage plan would mean a limited network of doctors and the potential need for preapproval, or prior authorization, from the insurer before getting care. The experience, he said, made getting care more difficult, and now he wants to switch back to traditional, government-administered Medicare.

But he can’t. And he’s not alone.

“I have very little control over my actual medical care,” he said, adding that he now advises friends not to sign up for the private plans. “I think that people are not understanding what Medicare Advantage is all about.”

Enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans has grown substantially in the past few decades, enticing more than half of all eligible people, primarily those 65 or older, with low premium costs and such perks as dental and vision insurance. And as the private plans’ share of the Medicare patient pie has ballooned to 30.8 million people, so, too, have concerns about the insurers’ aggressive sales tactics and misleading coverage claims.

Enrollees, like Timmins, who sign on when they are healthy can find themselves trapped as they grow older and sicker.

“It’s one of those things that people might like them on the front end because of their low to zero premiums and if they are getting a couple of these extra benefits — the vision, dental, that kind of thing,” said Christine Huberty, a lead benefit specialist supervising attorney for the Greater Wisconsin Agency on Aging Resources.

“But it’s when they actually need to use it for these bigger issues,” Huberty said, “that’s when people realize, ‘Oh no, this isn’t going to help me at all.’”

Medicare pays private insurers a fixed amount per Medicare Advantage enrollee and in many cases also pays out bonuses, which the insurers can use to provide supplemental benefits. Huberty said those extra benefits work as an incentive to “get people to join the plan” but that the plans then “restrict the access to so many services and coverage for the bigger stuff.”

David Meyers, assistant professor of health services, policy, and practice at the Brown University School of Public Health, analyzed a decade of Medicare Advantage enrollment and found that about 50% of beneficiaries — rural and urban — left their contract by the end of five years. Most of those enrollees switched to another Medicare Advantage plan rather than traditional Medicare.

In the study, Meyers and his co-authors muse that switching plans could be a positive sign of a free marketplace but that it could also signal “unmeasured discontent” with Medicare Advantage.

“The problem is that once you get into Medicare Advantage, if you have a couple of chronic conditions and you want to leave Medicare Advantage, even if Medicare Advantage isn’t meeting your needs, you might not have any ability to switch back to traditional Medicare,” Meyers said.

Traditional Medicare can be too expensive for beneficiaries switching back from Medicare Advantage, he said. In traditional Medicare, enrollees pay a monthly premium and, after reaching a deductible, in most cases are expected to pay 20% of the cost of each nonhospital service or item they use. And there is no limit on how much an enrollee may have to pay as part of that 20% coinsurance if they end up using a lot of care, Meyers said.

To limit what they spend out-of-pocket, traditional Medicare enrollees typically sign up for supplemental insurance, such as employer coverage or a private Medigap policy. If they are low-income, Medicaid may provide that supplemental coverage.

But, Meyers said, there’s a catch: While beneficiaries who enrolled first in traditional Medicare are guaranteed to qualify for a Medigap policy without pricing based on their medical history, Medigap insurers can deny coverage to beneficiaries transferring from Medicare Advantage plans or base their prices on medical underwriting.

Only four states — Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, and New York — prohibit insurers from denying a Medigap policy if the enrollee has preexisting conditions such as diabetes or heart disease.

Paul Ginsburg is a former commissioner on the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, also known as MedPAC. It’s a legislative branch agency that advises Congress on the Medicare program. He said the inability of enrollees to easily switch between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare during open enrollment periods is “a real concern in our system; it shouldn’t be that way.”

The federal government offers specific enrollment periods every year for switching plans. During Medicare’s open enrollment period, from Oct. 15 to Dec. 7, enrollees can switch out of their private plans to traditional, government-administered Medicare.

Medicare Advantage enrollees can also switch plans or transfer to traditional Medicare during another open enrollment period, from Jan. 1 to March 31.

“There are a lot of people that say, ‘Hey, I’d love to come back, but I can’t get Medigap anymore, or I’ll have to just pay a lot more,’” said Ginsburg, who is now a professor of health policy at the University of Southern California.

Timmins is one of those people. The retired veterinarian lives in a rural community on Whidbey Island, just north of Seattle. It’s a rugged, idyllic landscape and a popular place for second homes, hiking, and the arts. But it’s also a bit remote.

While it’s typically harder to find doctors in rural areas, Timmins said he believes his Premera Blue Cross plan made it more challenging to get care for a variety of reasons, including the difficulty of finding and getting in to see specialists.

Nearly half of Medicare Advantage plan directories contained inaccurate information on what providers were available, according to the most recent federal review. Beginning in 2024, new or expanding Medicare Advantage plans must demonstrate compliance with federal network expectations or their applications could be denied.

Amanda Lansford, a Premera Blue Cross spokesperson, declined to comment on Timmins’ s case. She said the plan meets federal network adequacy requirements as well as travel time and distance standards “to ensure members are not experiencing undue burdens when seeking care.”

Traditional Medicare allows beneficiaries to go to nearly any doctor or hospital in the U.S., and in most cases enrollees do not need approval to get services.

Timmins, who recently finished immunotherapy, said he doesn’t think he would be approved for a Medigap policy, “because of my health issue.” And if he were to get into one, Timmins said, it would likely be too expensive.

For now, Timmins said, he is staying with his Medicare Advantage plan.

“I’m getting older. More stuff is going to happen.”

There is also a chance, Timmins said, that his cancer could resurface: “I’m very aware of my mortality.”

Sarah Jane Tribble is a reporter for KFF Health News