David Warsh: Ukraine and Iraq

Pink shows extent of Russian occupation now.

Bodies of civilians shot by Russian soldiers lie on a street in Bucha, Ukraine The hands of one of the victims are tied behind his back.

—- Ukrinform TV

A children's hospital in Mariupol, Ukraine, after a Russian airstrike The city was mostly destroyed last year by Russian forces.

— Photo from armyinform.com.ua

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The failures of Silicon Valley and Signature banks were an addictive story these last few days. Humiliation for the start-up sector. Red meat for progressives. Field maneuvers for the financial press. A stress test for the bank-regulatory system, which failed, and for the Biden administration, which passed. It was not, however, the most important story of the week.

The bigger story was the news of the first shots fired in the battle that looms in next year’s presidential election over U.S.-led NATO support for Ukraine in its resistance to Russia’s invasion.

Protecting the independent nation from Russian absorption “is not a vital US interest,” said Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis in a statement to Fox News host Tucker Carlson last week. A quartet of Washington Post (and their editors) promptly jumped on the news. DeSantis’s position “firmly [put] the potential presidential candidate on the side of Donald Trump, and at odds with top Congressional Republicans.”

The presidential-contender continued,

“While the U.S. has many vital national interest – securing our borders, addressing the crisis of readiness with our military, achieving energy security and independence, and checking the economic, cultural, and military power of the Chinese Communist Party – becoming further entangled in a territorial dispute between Ukraine and Russia is not one of them.”

Two days later, the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal headlined “DeSantis’s First Big Mistake.” The two-term Florida governor enjoys a a reputation as “a fearless fighter for principle who ignores the polls,” the editorialists noted. “Then how to explain his puzzling surrender this week to the Trumpian temptation of American retreat?” The editorialists answered their own question before providing an out:

“The argument goes that Mr. DeSantis is reading the political mood. About 40 percent of Republicans say that the U.S. is providing “too much support” for Ukraine, up from 9 percent in March last year. Yet some of this is a function of polarized U.S.p olitics. Many Republicans oppose helping Ukraine because Mr. Biden is doing it, an the mirror image is Democrats from an anti-war left putting Ukrainian flag stickers on their electric cars…. Mr. DeSantis is clearly still refining his views and his remarks on Ukraine left some room to improve them later.”

The spectacle of the two American wings of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire disagreeing so sharply about a fundamental matter presage a far wider and more complicated battle next year.

I’ve criticized NATO enlargement for twenty-five years. I was therefore painfully conflicted by Vladimir Putin’s ham-handed invasion of Russian’s southern neighbor. It may have been understandable, but it was profoundly wrong. Still, I think of myself as center-left. How is it I now find myself allied with Tucker Carlson, Donald Trump, Ron DeSantis and Keri Lake?

I can only dream that they finally listened to me. Or, more likely than that, to Jeffrey Sachs, head of Columbia University’s Earth Institute, a long-time center-left maverick (see his “The Ninth Anniversary of the Ukrainian War;”, to veteran antiwar-journalist Seymour Hersh (“Who’s your George Ball?”; or even to film-maker Oliver Stone (“Ukraine on Fire”).

I don’t have poll numbers to show it, but my hunch is that something like 40 percent of all Democrats also have begun to believe that the U.S. is spending too much money or risk on Ukraine’s defense of itself, though President Biden and Senate leaders of both parties continue to strongly support the funding the war. DeSantis, like Trump, may suspect as much himself. He is an opportunist, as all politicians are, though less nimble than Trump.

I expect that Joe Biden and the Congressional leadership will have the advantage in 2024. I disagree with Biden’s foreign policy but I will vote for him if he runs again. Probably he will win – it won’t be easy for a Republican candidate to run on a call for retreat (never mind all the domestic issues!)

But a second term for the aging Biden would mean he will have to bear the burden if the defense of Ukraine ultimately fails. That depends on what happens on the battlefield, of course, where the advantages seems mostly to be Putin’s. When the war ends, political realignment in America will begin.

. xxx

Twenty years ago today, the morning of March 19, 2003, a U.S.-dominated coalition of forces began bombing Baghdad. The US had demanded that Saddam Hussein leave Iraq within 48 hours. When he didn’t, coalition forces attempted to kill him and his sons in the first hour of their “shock and awe” invasion. They didn’t succeed. President George W. Bush went on television that evening to describe the purpose the war to follow: “to disarm Iraq, to free its people, and to defend the world from grave danger.”

The invasion of Iraq was the fulcrum on which much has shifted since. In a speech to the Munich Conference on Security Policy, in February 2007, Vladimir Putin dissented sharply from Washington’s vision of a unipolar world and warned against further NATO expansion along Russia’s southern borders. It is worth noting that Putin borrowed heavily from the US playbook for his invasion of Ukraine last year, including the attempted decapitation of the Zelensky government leadership team.

It didn’t work any better in Kyiv than in Baghdad.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Say goodbye to the Monroe Doctrine

John Quincy Adams, who as President James Monroe’s secretary of state, was one of the fathers of the Monroe Doctrine, which was announced on Dec. 2, 1823.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Everybody agreed that the language was blunt. China’s president, Xi Jinping, last week told a national audience, “Western countries led by the United States have implemented all-round containment, encirclement and suppression of China, which has brought unprecedented grave challenges to our nation’s development,” Xi was quoted as saying by the official Xinhua News Agency.

The next day Gen. Laura J. Richardson, commander of the U.S. Southern Command, which is responsible for South America and the Caribbean, testified before the House Armed Services Committee that China and Russia were “malign actors” that are “aggressively exerting influence over our democratic neighbors…” She continued:

Among other activities, China has built a massive embassy in the Bahamas, just 80 kilometers (50 miles) off the coast of Florida. “Presence and proximity absolutely matter, and a stable and secure Western Hemisphere is critical to homeland defense.

The day after that, Saudi Arabia and Iran agreed to re-establish diplomatic ties, The Middle East powers have a long history of conflicts. China hosted the talks that led to the breakthrough. Peter Baker, of The New York Times, wrote,

This is among the topsiest and turviest of developments anyone could have imagined, a shift that left heads spinning in capitals around the globe. Alliances and rivalries that have governed diplomacy for generations have, for the moment at least, been upended.

With good books piling up on my side table – Accidental Conflict: America, China, and the Clash of False Narratives (Yale, 2022), by Stephen Roach; Danger Zone: The Coming Conflict with China (Norton, 2022), by Hal Brands and Michael Beckley; Cold Peace: Avoiding the New Cold War (Liveright, 2023), by Michael Doyle – I decided instead to look back at a 12-year old book, Time to Start Thinking: America in the Age of Descent (Atlantic Monthly Press), by Edward Luce.

Roach, an economist, is a former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia. Brands, a historian, is a professor at Johns Hopkins University. Beckley, a political scientist, is an associate professor at Tufts University. Michael Doyle, a political scientist, is a professor at Columbia University.

But Luce is the U.S. national editor and columnist of the Financial Times, and his column last week appeared under the headline, “China is Right about U.S. Containment,”

[L]oose talk of U.S.-China conflict is no longer far-fetched. Countries do not easily change their spots. China is the middle kingdom wanting redress for the age of western humiliation; America is the dangerous nation seeking monsters to destroy. Both are playing to type.

The question is whether global stability can survive either of them insisting that they must succeed. The likeliest alternative to today’s U.S.-China stand-off is not is not a kumbaya meeting of minds but war.

When I picked up Luce’s The Time to Start Thinking, what struck me was how pessimistic his tone was. He had taken nine months off from his newspaper, traveling for six months and writing for three. He recorded encounters with all kinds of Americans, mostly powerful, some without power. His title came from the Sir Ernest Rutherford, winner of the 1908 Nobel Prize in Chemistry: “Gentleman, we have run out of money. It is time to start thinking.” I was reminded immediately of Aaron Friedberg’s The Weary Titan: Britain and the Experience of Relative Decline, 1895-1905.

Luce was writing in the aftermath of a lengthy recession, the Tea Party election, the 2008 financial crisis, and the debacle of the U.S. war in Iraq. The last chapter begins, “Why the coming struggle to reverse America’s decline faces long odds.” It concludes, “The truth is America’s stock has been falling around the world for quite a while…. Simply proclaiming the superiority of the American model is not helping anyone’s credibility.” Ahead lay the presidencies of Donald Trump and Joe Biden, and an ill-understood war in Ukraine.

Yet last week Luce was warning against the folly of trying to “contain” China’s expansion on the basis of the Cold War blueprint that worked well against the Soviet Union, encouraging the U.S. to compete on its merits instead. “Unlike the USSR, which was an empire in disguise, China inhabits historic boundaries and is never likely to dissolve. The U.S. needs a strategy to cope with a China that will always be there… Betting on China’s submission is not a strategy.

Instead, Luce counseled, the U.S. should muster its revolve and rely on its advantages. It has “plenty of allies, a global system that it designed, better technology, and younger demographics.” China is aging, its growth is slowing, though its leaders nurse ambitions not to change, but to set the rules of the game. The big difference that Luce stressed in 2012, while China is still flush, the US has overspent.

So what will it be? War over Taiwan? A symbolic moon-race to AI? Or a sometimes-smoldering era of systemic competition in all four corners of the earth? We are not out of money, but it is well past the time to start thinking.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Will geoengineering be needed to stem global warming?

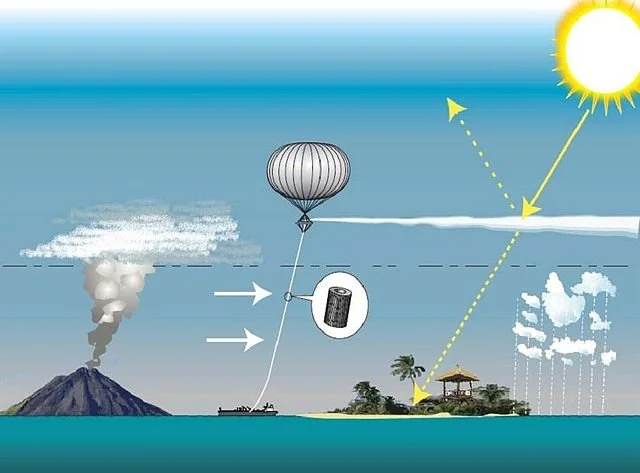

Proposed solar geoengineering using a tethered balloon to inject sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Of the three broad approaches to coping with the effects of global warming – reduction of greenhouse-gas emissions; various adaptations to a warmer world, and solar-radiation management – it is the idea of climate intervention, or “geoengineering,” as its enthusiasts often describe it, that engenders the most fear.

We know that the natural version works: Volcanic eruptions over the millennia have demonstrated that much. Volcanic dust spewed into high altitudes has reduced temperature over significant portions of the Earth’s surface in the past, by making the atmosphere more reflective of the sun’s rays.

But the idea of deliberately pumping sulfates into the stratosphere to reduce global temperatures appears to some so risky, if only by dint of the “not-to-worry” incentive it seems to imply, that some climate scientists – their opinions buttressed by Under a White Sky, the book and Snowpiercer, the film – have called for a ban any geoengineering research at all.

That would clearly be foolish. The good news is that Science magazine last month reported that the first cautious attempts to understand the Earth’s “radiation budget” have begun. Prodded by Congress, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has launched a program to understand “the types, amounts and behavior of particles naturally present in the stratosphere.” SilverLining, an interesting non-governmental lobbying organization, is also involved.

[T]the balloons and high-altitude aircraft in the program aren’t releasing any particles or gases. But the large-scalefield campaign is the first the U.S. government has ever conducted related to solar geoengineering. It’s very basic research, says Karen Rosenlof, an atmospheric scientist at NOAA’s Chemical Sciences Laboratory. “You have to know what’s there first before you can start messing with that.”

An appropriately cautious beginning. I don’t know how humankind will gradually solve the climate-change problem, but I am pretty confident that it will, through some combination of alternative fuels; massive adaptations, both physical and social; and, probably, some degree of geoengineering. I am reminded of the Christian hymn text that William Cowper wrote , in 1773, so apropos today that it is worth quoting at some length. A great deal has happened in those 250 years, of course, so feel free to substitute “Evolution” for “God,” if you prefer. It still scans.

God moves in a mysterious way,

His wonders to perform;

He plants his footsteps in the sea,

And rides upon the storm.

Deep in unfathomable mines

Of never failing skill;

He treasures up his bright designs,

And works His sovereign will.

Ye fearful saints fresh courage take,

The clouds ye so much dread

Are big with mercy, and shall break

In blessings on your head.

Judge not the Lord by feeble sense,

But trust him for his grace;

Behind a frowning providence,

He hides a smiling face….

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

David Warsh: Defense of and attack on government debt

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Weary of reading play-by-play stories about the Treasury Department’s efforts to manage in light of the hold-up by right-wing Republicans over reaching the federal debt ceiling – impoundment decisions, discharge petitions and various accounting maneuvers – I took down my copy of Barry Eichengreen’s In Defense of Public Debt (Oxford, 2021) to remind me of what, at bottom, the fracas is all about.

Eichengreen, an economic historian at the University of California at Berkeley, is still not yet a household word in homes where economics is dinner-table conversation, though earlier this month he was named (with four others) a distinguished fellow of the American Economic Association, the profession’s highest honor.

He was recognized chiefly for having written Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression 1919-1939 (Oxford, 1992), which has become the standard account of how the Great Depression was so globally damaging – the role that the gold standard played in transmitting around the world its origins in the United States.

But it was sheer good citizenship that led Eichengreen and three other experts – Asmaa El-Ganainy, Rui Esteves and Kris James Mitchener – to write what their publisher describes as “a dive into the origins, management, and uses and misuses of sovereign debt through the ages.” Their Defense turns out. too, to be useful in looking ahead to what is said to be a looming crisis of global debt. .

Their book begins with another dramatic moment of American civic life: Sen, Rand Paul (R.-Ky.) inveighing in December 2020, against government borrowing earlier that year on news of the outbreak of the global Covid pandemic:

How bad is our fiscal situation? Well, the federal government brought in $3.3 trillion in revenue last year and spent $6.6 trillion, for a record-setting $3.3 trillion deficit. If you are looking for more Covid bailout money, we don’t have any. The coffers are bare. We have no rainy day fund. We have no savings account. Congress has spent all of the money.

Paul’s alarm was based on a fundamental insight, Eichengreen and his co-authors write, namely that governments are responsible for their nations’ finances. If they borrow frivolously, or excessively, bad consequences usually follow, On the other hand, if national governments fail to borrow in a genuine emergency – to fight a war deemed necessary; to staunch a financial panic; to facilitate a domestic political pivot – even worse damages might ensue. The sword is two-sided: Public debt has its legitimate uses, after all. .

A market for sovereign debt has existed for millennia. Kings and war-lords borrowed, most often to wage war. They paid exorbitant interest rates because they often defaulted. It was only in the 17th Century, as modern nations began to emerge, that viable institutions of public debt were established, first in England and the Netherlands.

Constitutional governments, with legislatures and parliaments, made it possible for would-be lenders to participate in decisions to borrow, to engineer realistic hopes of getting their money back, as they turned in the coupons they clipped from their government bonds in exchange for semi-annual payments of interest. Advice and consent became part of the game.

From the beginning, there was ambivalence. In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith himself warned that it would be all to easy for nations to borrow profligately against the promise of future tax revenues, Eichengreen noted. Smith made an exception mainly for war. As it turned out, the stabilization of British government debt markets organized by Robert Walpole after the disastrous South Sea Bubble, which popped in 1720, became the original military industrial complex. Many scholars credit superior borrowing capacity for Britain’s eventual victory in the Napoleonic Wars.

Government borrowing expanded to other purposes in the 19th Century, Eichengreen writes, especially for investments in canals and railroads intended to foster geographic integration and growth. Central banks learned how to halt financial panics by serving as lenders of last resort.

In the 20th Century, he says, the emphasis shifted again, this time to social services and transfer payments. Government borrowing financed the creation of the modern welfare state. And, of course, governments continue to shoulder the responsibility to maintain overall financial stability.

Today, the argument is between “conservative” radicals who hope to disassemble the welfare state, and radical “progressives,” who seek to expand it with little concern for the dangers of borrowing too much. In the center are a large corps of sensible citizens, such as Eichengreen, who seek to harness the existing system of taxing and borrowing and spending to let it work in a sensible and less expensive manner.

The market for government debt has survived, Eichengreen notes, “indeed thrived, for the better part of five hundred years.” It is an indispensable part of the world’s fiscal plumbing. Tinkering with it is fine; holding it hostage makes no sense at all. In Defense of Public Debt is an excellent primer on all these issues. I haven’t done it justice, but I started too late, and have run out of time.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Deconstructing Hayek; does market get technology’s direction right?

John Singer Sargent's iconic World War I painting “Gassed”, showing blind casualties on a battlefield after a mustard gas attack. The same chemists’ work had resulted in creating highly useful fertilizers — and poison gas and very powerful explosives.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I was looking forward to the session on Hayek at the economic meetings in New Orleans last week. As a soldier of the revolution, I had learned a good deal from Hayek back in the day, when his occasional pieces sometimes appeared in Encounter magazine. (I knew Hayek had been the prime mover behind the founding of the classically liberal pro-markets Mont Pelerin Society in 1947; knew, too, that Encounter has been partly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency, in 1953, in an effort to counter Cold War ambivalence.

I understood that Hayek was one of a handful of economists who had been especially influential before John Maynard Keynes swept the table in the Thirties. Others included Irving Fisher, Joseph Schumpeter, A.C. Pigou, Edward Chamberlin, and Wesley Clair Mitchell. What revolution? We journalists were hoping to glimpse economics whole. The economists whom we read (and other social scientists, historians, and philosophers) seemed as blind men handling an elephant. Each described some part of the truth.

The session devoted to Bruce Caldwell’s new biography, Hayek: A Life: 1899-1950 (Chicago, 2022), didn’t disappoint. Presiding was Sandra Peart, of the University of Richmond, an expert on the still-born Virginia school of political economy of the Fifties (as opposed to the Chicago school of economics), with which Hayek was sometimes connected. Cass Sunstein, of the Harvard Law School; Hansjörg Klausinger, of Vienna University of Economics and Business; and Vernon Smith, of Chapman University, zoomed in. Steven N. Durlauf, of the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy (and editor if the Journal of Economic Literature); Emily Skarbek, of Brown University, were present discussants; as was, of course, Caldwell himself. The reader-friendly Hayek: A Life was itself the star of the show: a gracefully documented and thoroughly knowledgeable story of Vienna, New York, Berlin, London and Chicago, during those luminous years. I look forward to the second volume, 1950-1992.

Then I walked half a mile down New Orleans’ Canal Street to hear the American Economic Association Distinguished Lecture by Daron Acemoglu, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This was a very different world from that of Hayek.

For one thing, “Distorted Innovation: Does the Market Get the Direction of Technology Right?” wasn’t really a lecture at all. It was a technical paper, presenting a simple mode of directed technology, with which Acemoglu has been working for twenty-five years, followed by discussions of several examples of what Acemoglu described as instances in which technologies have become distorted by shifting incentives: energy, health and medical markets; agriculture; and modern automation technologies. The paper begins in jaunty fashion,

There is broad agreement that technical change has been a major engine of economic growth and prosperity during the last 250 years, However not all innovations are created equal and the direction of technology matters greatly as well.

What constitutes the “direction of technical change?” Acemoglu offered a striking example. Early 20th-century chemists in Germany, led by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch, developed an industrial process for converting atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia. Synthetic fertilizers thereby rendered commercial, greatly improved agricultural yields around the world. But the same processes were employed in industrial production of potent explosives and poisonous gases which killed millions of soldiers and civilians during World War I. Which direction might an effective social planner have preferred?

One view, the one for which Hayek is famous, is that the market is the best judge of which technologies to develop. There may be insufficient incentives to innovate initially, but once the government provides the requisite research infrastructure and support, it should stand aside. What the market thinks right, meaning profitable, is right, in this view.

Diametrically opposite, Acemoglu said, is the view that the politicians, planners and bureaucrats can decide on these matters as well as or even better than markets, and therefore they should set both the overall level of innovation and seek to influence its direction. This is welfare economics, a style of economic analysis pioneered after 1911 by A.C. Pigou, then the professor of economics at Cambridge University, and, for twenty-five years, perhaps the most influential economist in the world.

In his paper Acemoglu sought to describe an intermediate position, in which markets exist to experiment in order to determine which innovations are feasible, whereupon planners have a role in applying economic analysis to gauge otherwise unexamined side-effects of various sorts that may arise from a pursuing a particular path.

It was an unusual lecture, pitched to the level of a graduate seminar, and even before Acemoglu finished, individuals began drifting off to dinner engagements. The good news is that there is a book on its way. Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity (Public Affairs),by Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson will appear in May. Still better news is that it tackles head-on questions about automation, artificial intelligence, and income distribution that currently abound.

With three big books behind him — Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy; Why Nations Fail; and The Narrow Corridor, all with James Robinson, of the University of Chicago Harris School – behind him, Acemoglu is among the leading intellectuals of the present day. As heir to the leadership roles played by Paul Samuelson, Robert Solow, and Peter Diamond, he packs intuitional punch as well. Pay attention! Get ready for a battle royale.

The tectonic plates of scientific economics are shifting — large-scale processes are affecting the structure of the discipline. That revolution I mentioned at the beginning? The one in whose coverage we economic journalists are engaged? Its fundamental premise is that, while politics always plays a part in the background, economics makes progress over the years. In other words, Hayek takes a back seat to Acemoglu.

David Warsh: Support Ukraine but study the path to war

"The Chateau" at St. Basil College, in Stamford, Conn., was originally a college dormitory and now houses the Ukrainian Museum and Library of Stamford.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I have lived with the possibility of war in Ukraine for a long time, first as a newspaper columnist, then as a newsletter writer (and a long-ago war correspondent). I wrote against further NATO enlargement soon after Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary were admitted – gingerly at first, more firmly once I began covering the Harvard-Russia scandal in the mid-’90s.

Boris Yeltsin’s selection of Vladimir Putin to be his successor didn’t seem surprising. Unlike Hillary Clinton, I was not shocked when, in 2012, Putin took back the helm from Dimitri Medvedev. Putin wasn’t a czar, but by then he was steering Russia’s course.

The events of 2014 did alarm me – Putin’s plans for a gradual takeover of Ukraine, foiled by US-supported demonstrations in Kyiv’s Maiden Square, followed by Russia’ stealth repossession of the Crimean peninsula. In 2016, expecting that Clinton would be elected, I began writing Because They Could: The Harvard-Russia Scandal (And NATO Expansion) after Twenty-five Years (Create Space, 2018)

Instead Donald Trump was elected. His longstanding relationship with Russian government and various Russians put the matter on hold. Joe Biden defeated Trump four years later and the momentum of NATO expansion was seamlessly reasserted, notably with signing on Nov. 10, 2021 of a U.S.-Ukraine Charter of Strategic Partnership. Barely three months later, Putin attempted his ill-fated blitzkrieg. The subsequent invasion was mostly turned back, except in the eastern Donbass region.

What’s done is done. The issue seems to me to have been decided, mostly by the citizens and soldiers of Ukraine. The U.S. may or may not bear responsibility for having fomented the war by pressing the boundaries – and the culture – of NATO ever closer to Russia, but having reached this point in Putin’s war on Ukraine, America has no honorable alternative but to stay the course until Putin stands down. He will do so only after more defeats on the battlefield; after taking account of the devastation he has caused, no less to his own country than to Ukraine; and to Russia’s reputation forever. His pursuit of restoration of Russian status as a superpower was a pipedream.

What is next? Partition is apparently what the Pentagon expects, once Russia’s spring offensive grinds to a halt. That makes sense to me. Russia gets to keep portions of Eastern Ukraine that it already possesses. Ukraine retains what it has already recaptured; remains independent; and gradually becomes a member of NATO and the European Union.

In the meantime, continued support for Ukraine is about to become a matter of partisan politics in the 2024 presidential election campaign. So much the better: it will be one more litmus test with which to separate the real Republican Party from Trumplican rear-guard. The war in Ukraine offers an opportunity to begin to put US politics together again.

It is time to begin to gather assessments of America’s behavior in world affairs during the last thirty years. Historian M. E. Sarotte has made an especially good start with her most recent book, Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post- Cold War Stalemate (Yale, 2021), but, as she notes, her account covers only the beginning; it ends in 1999. Her next volume presumably will cover the years to 2016. By that time, today’s war will be over, and the saga of the post- Cold War world ripe for a third volume.

Frank Costigliola’s biography Kennan: A Life between Two Worlds (Princeton, 2023) adds some details to the story of diplomat George Kennan’s famous op-ed piece opposing NATO expansion, “A Fateful Error,” in The New York Times, in 1996, but we will have to wait some time for a dispassionate biography of Strobe Talbott, President Clinton’s old Oxford friend, the architect of NATO expansion. Newspaper journalists, Peter Baker of The Times foremost among them, can be expected to begin to illuminate some shadows.

The change of heart about the war that I’m describing – putting aside for now the idea of joint responsibility in favor of rendering sufficient support to Ukraine, whatever it costs, until independence and peace are won – has been a long and painful time in coming. America has not done well in its three major wars in my adulthood – Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq. In Ukraine, it finally seems vital to stay the course.

xxx

I caught a windjammer of a cold over the holidays and failed to post to EcononomicPrincipals.com in timely fashion what he had written before the storm. He put it up when calm returned. Apologies to those accustomed to reading it there.

More to the point, all good wishes to readers for the coming year.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Those missed Nobel Prizes

Front side of a Nobel Prize.

Photo by Jonathunder

SOMERVILLE, Mass.,

When Dale Jorgenson died last summer, of long Covid, at 89, sighs were heard throughout the worldwide community of measurement economists. Had the Swedish authorities at long last been preparing to recognize the founder of modern growth accounting? Did the Reaper rob the Harvard University econometrician of his Nobel Prize?

Probably not. It seemed that, barring exigency, the Nobel panel had decided long ago to pass him by. It was left to Martin Baily, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, to tell The Wall Street Journal’s James Hagerty that Jorgenson “should have been awarded a Nobel Prize….” The same has been said of many other often-nominated candidates, including, for example, American novelists Philip Roth, of Connecticut, and John Updike, of Massachusetts.

On a memorial service yesterday, in Harvard’s Memorial Church, it almost didn’t matter. The talk was of families, friendships, skits (including one in which Jorgenson was portrayed as Star Trek’s Mr. Spock): the old days, when the Harvard Economics Department’s youngers members and their students were housed in a converted hotel across the street from IBM’s mainframe computers. Colleagues Barbara Fraumeni, Mun Sing Ho and Benjamin Friedman spoke; so did Jorgenson’s former student Lawrence Summers. Another former student, Ben Bernanke, whose undergraduate thesis Jorgenson supervised, missed the service, on his way to Stockholm to share a Nobel Prize; the two had remained in life-long touch.

Still, the question remained, why not Jorgenson?

Certainly it was not for lack of dominating achievements in his chosen field, of growth and productivity measurement. Born in 1933, Jorgenson grew up in Montana, attended Reed College, in Portland, Ore., and, in 1959, received his PhD from Harvard, where future Nobel laureate Wassily Leontief had supervised his thesis. He took a job at the University of California at Berkeley, where he taught the graduate theory course.

In 1963 Jorgenson published “Capital Theory and Investment Behavior.” When a committee selected the 20 most important papers that the American Economic Review had published in its centenary celebration, Jorgenson’s article was among them – the only contribution to have appeared in print immediately, without the customary wait for referee reports. The 13-page paper was revolutionary in two ways, according to Robert Hall, of Stanford University:

It combined finance with the theory of the firm to generate a coherent theory of the firm’s purchase of capital inputs, an area of considerable confusion prior to Jorgenson’s work. And it also laid out a paradigm for empirical research that called for serious economic theory to provide the backbone of the measurement approach. Jorgenson showed how to integrate data and theory.

As Berkeley boiled over with student protests in the 1960s, its best economists began to leave for Harvard: first Richard Caves and Henry Rosovsky, then David Landes, and, in 1969, Jorgenson. They were part of Harvard’s response to having been eclipsed in economics beginning 25 years earlier, by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Kenneth Arrow, Zvi Griliches, Martin Feldstein, and John Meyer were recruited as well, from Stanford, Chicago, Oxford and Yale respectively.

In 1971, Jorgenson won the bi-annual John Bates Clark Medal, awarded for contributions to economics before the recipients turned 40, as had Griliches, in 1965, and Arrow, in 1957. Feldstein would be similarly recognized in 1977.

Jorgenson’s contributions continued at a steady pace for more than 50 years at Harvard. The most significant of these was a successful campaign to produce industry-by-industry input-output tables with which to elucidate national income accounts prepared in the 1930s. Aggregate growth accounting depended fundamentally on the concept of value-added, according to John Fernald, author of a comprehensive account of Jorgenson’s career.

But Evsey Domar had written as early as 1961 that value-added accounting was only “shoes lacking leather and made without power.” To identify the changes occurring in productivity a complete set of input-output tables would be required, disaggregated by industry, linking Leonief/Jorgenson accounting with the old national income accounts designed by Nobel laureate Simon Kuznets. .

Working with Ernst Berndt, Frank Gollop and Barbara Fraumeni, among others, Jorgenson gradually created a granular new account of the sources of growth, differentiating between inputs of capital (K), labor (L), energy (E), and materials (M). The purchase of services (S) were subsequently broken-out. Hence the KLEMS system of productivity and growth accounting, now used by governments around the world. Jorgenson served as president of the American Economic Association in 2000.

I knew Jorgenson as news people know their subjects, and I have known many of his students, too. I never followed growth accounting closely, though I read Diane Coyle’s beguiling little book GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History (Princeton, 2014), and I was sufficiently absorbed by Fernald’s Intellectual Biography of Jorgenson to suspect that a second golden age of nation income and productivity accounting, or perhaps one of platinum, already has begun. (For an especially artful introduction to the KLEMS system, see Emma Rothschild’s essay, “Where is Capital?” in Capitalism: A Journal of History and Economics).

Nor do I know much about early 19th Century naval history. There was, however, something in Jorgenson’s leadership style (and a leader he unmistakably was) that reminded me of the lore surrounding Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson – his precise and formal manner, clipped speech, wry humor, zest in explaining to friends the innovations he prepared, and the admiration and loyalty he elicited from his students and colleagues.

Hearing their stories over the years, I was reminded one day of the signal that Nelson sent his squadrons as the battle of Trafalgar was about to begin – “England expects that every man will so his duty.” Never mind that “the little touch of Dale in the night” sometimes meant wakefulness on nights before examinations. More often his most successful students spoke of encouragement and surprising warmth. Further evidence of the inner man: a 50-year marriage to a professionally successful wife, two children (he worked at home three days a week) and three grandchildren.

If Jorgenson’s sense was that the Swedes, too, would do their duty, apparently they did not conceive their duty quite the same way. Perhaps the pride he took in his work was too obvious to them. He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1989, sometimes seen as a consolation prize. Perhaps too much umbrage had been given MIT; there were those 13 volumes of Jorgenson’s collected papers, published with the author’s subvention, five more than those of Paul Samuelson; Griliches had been embarrassed to publish one. (The one-time collaborators (“The Explanation of Productivity Change,” in 1967) were often nominated together for their complementary work.)

Griliches died in 1999; Jorgenson soldiered on, adding to his portfolio the economics of energy, the environment, emerging nations’ development, and even pandemics, via the KLEMS system. He became embedded in the major tax debates of the day. But the attention that theoretical economists paid to increasing returns to scale beginning in the ‘80’s was of little interest to an apostle of neo-classically based empirical analysis.

Jorgenson was sometimes called a “Reedie,” after the selective college he attended, celebrated for a distinctive sort of intellectuality, rivaled by Cal Tech, Swarthmore College and St. Johns College. Some 1,500 undergraduates today, 175 faculty members, providing constant feedback but no grades in real time, a measure thought to encourage hard work and long horizons. Only after they had graduated and applied to graduate schools were their transcripts revealed. Legend had it that Jorgenson was among the handful who over the years had received straight A grades in all his courses, and perhaps a few beyond. Certainly he received encouragement from Carl M. Stevens, a 1951 Harvard PhD in economics then teaching at Reed.

Touring a plaza of his hometown library that had been named for him, the author Phillip Roth was asked if the cold-shoulder from the Swedish Academy bothered him. “Newark is my Stockholm,” Roth replied. Reed College was Jorgenson’s Newark; bi-annual KLEMS project meetings are his Stockholm.

David Warsh, veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Tech presbyopia helped cause crypto apocalypse

Number of Bitcoin transactions per month (logarithmic scale)

“Valhalla in Flames,’’ by Max Bruckner.

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

I have paid little attention to the collapse of crypto-mania because, since it has been clear all along that it was a fraud perpetrated on the greedy and gullible by a coterie of tech-savvy young.

The so-called crypto currencies were simply unregulated banks, their accounting dubious, their lending practices opaque, their valuations in public markets jacked up to preposterous heights by leverage. As Wall Street Journal columnist Greg Ip wrote in a piece published Nov. 27

While bankruptcy filings aren’t entirely clear, they describe many of the largest creditors as customers or other crypto-related companies. Crypto companies, in other words, operate in a closed loop, deeply interconnected within that loop but with few apparent connections of significance to traditional finance. This explains how an asset class once worth roughly $3 trillion could lose 72% of its value, and prominent intermediaries could go bust, with no discernible spillovers to the financial system.

Block chain technology, on the other hand, has interested me ever since Bitcoin, in 2008, introduced its possibilities to the modern world. Interested, that is, but not enough to do much about it.

It is no accident that the best timeline on the inspiration behind block chain technology I could quickly find last week was published by the Institute of Charters Accountants of England and Wales (ICAEW). That is because the ICAEW, with its 150,000 well-compensated members, and their counterparts enrolled in similar organizations around the world, represent the profession of trusted book-keepers whose livelihoods are threatened in some degree by the new digital technology. Threatened someday, that is – not all at once, but eventually, in 10 to 20 years.

Nor is it surprising that the ICAEW is pretty good on the details of the invention of the threat to the accountancy profession. (Here is a slightly more informative version.) A couple more clicks led to this highly readable digest, The little-known history of block chain, as told by its inventors, by Greg Hall, on a Bitcoin Association Web site.

It turns out that the inventors of the technology behind block chain were working for Bellcore, descendent of the old Bell Laboratories, owned in 1991 by the seven Baby Bells, when they began discussing how it might be possible to time-stamp a digital document. Stuart Haber had a PhD in computer science from Columbia University, Scott Stornetta was a Stanford-trained physicist. They shared an interest in cryptography, a lively topic at the time.

Stornetta knew how easy it was to doctor a digital document without anyone noticing. Society depends on trustworthy records – that is where the bookkeepers came in. But if a transition to entirely digital documents was inevitable, the problem was to create immutable records.

Haber and Stornetta figured out how. Hall writes, “The solution was to use one-way hash functions, take requests for registration of documents (which mean the hash values of the documents), group them into ‘units’ (blocks), build the Merkle tree and create a linked chain of hash values.” They presented their work to an international cryptology conference in Santa Barbara; block chain was born. For a better feel for the inventors, and the work that they did, watch the 10-minute YouTube interview at the end of Hall’s piece.

In 1998 a reclusive Hungarian computer scientist and lawyer named Nick Szabo began experimenting with a digital currency he called Bit Gold. In 2000, German cryptologist and software engineer Stefan Konst published a theory of cryptographically secured chains of data.

But only in 2008 did developers, working under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto, publish a workable model of a distributed ledger by then known as block chain. Bitcoin, the killer application, appeared the next year. And in 2014, a block chain 2.0 version was separated from the Bitcoin asset and offered for other kinds of transactions-reporting applications. By then cloud computing was a fact. The human block chain – the accounting profession with their ledgers and books – had been put on notice. Audit robots? Not so fast!

The Bitcoin world, though a reality, is still thronged with crypto-market evangelicals. To get out of it, I turned to Distributed Ledgers: Design and Regulation of Financial Infrastructure and Payment Systems (MIT, 2020), by Robert Townsend, a professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Townsend is a remarkable scholar. A general equilibrium theorist, trained at the University of Minnesota, he taught at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Chicago for 30 years.

In 1993, he published The Medieval Village Economy: A Study of the Pareto Mapping in General Equilibrium Models (Princeton.) and, in 1997, began his continuing Thailand Project (sample paper: The Village Money Market Revealed: Credit Chains and Shadow Banking). By 2021, he spent a year as the senior research fellow at the Bank for International Settlements, the central bankers’ central bank,” in Basel, Switzerland. And when disparate central bank digital currencies, with their distributed ledgers, are eventually stitched together, that is where the reconciliation will take place.

The cryptocurrency craze, a fraud of memorable proportions, was based on an acute case of what the legendary economic historian Paul David decades ago labeled technological presbyopia – the tendency to see clearly events as they will be, far ahead in time, while overlooking all the necessary steps to get there. For a sense of how long it takes for a new discovery to realize its full technological potential, read Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Crucial Technology (Scribner, 2022), by Chris Miller. Look for a similarly highly readable a book about distributed ledgers to appear in, say, another thirty years.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: Tim Ryan says time to ‘Leave the age of stupidity behind us’

“An Allegory of Folly” (early 16th century), by Quentin Matsys

— EC Publications

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was the one ostensible mistake I made in what I wrote about the run-up to what did in fact turn out to be a nobody-knows-anything election.

To my mind, the most interesting contest in the country is the Senate election involving 10-term Congressman Tim Ryan and Hillbilly Elegy author J. D. Vance, a lawyer and venture capitalist. That’s because, if Ryan soundly defeats Vance, he’s got a good shot at becoming the Democratic presidential nominee in 2024.

Even now I don’t think that I was altogether wrong.

Thanks to the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal, we know why Ryan lost. Vance, who was on the ballot because Donald Trump endorsed him, trailed Ryan by significant margins until mid-summer. That was when Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell invested more than $32 million in the Ohio Senate race, via a super-PAC he controlled, 77 percent of all Republican campaign media spending in the Ohio election after mid-August. Most of it was negative “voter education,” enough to tip the balance against “taxing-Tim” for having voted for various Biden measures. The power of money in American elections may be a scandal, but by now it has been well-established by the Supreme Court as a fact of life.

It seems nearly certain to me that the next president will be someone born in the ‘70’s, not the ‘40’s. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat was probably correct when he wrote last week that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is likely to be the Republican nominee. DeSantis, 44, was born in 1978.

Douthat may have been wrong, however, in thinking that DeSantis’s “sweeping success” in his re-election campaign validated the theory that “normal” doesn’t have to mean “squishy.” The tough-guy approach worked well in Florida. DeSantis was “an avatar of cultural conservatism, a warrior against the liberal media and Dr. Anthony Fauci, a politician ready to pick a fight with Disney if that’s what the circumstances require.”

But a better-mannered Donald Trump may not be what the majority of voters will be looking for in the next election. Tim Ryan, 49, was born in 1973. If you have time, and want a lift, watch Ryan’s 15-minute concession speech to get a feel for the man. Pay special attention to the six-minute mark, where Ryan speaks to the audience beyond the room he is in.

The words in that middle portion of that speech strike a powerful chord: “This country, we have too much hate, too much anger, there is way too much fear, way too much division. We need more love, more compassion, more concern for each other. These are important things. We need forgiveness, we need grace, we need reconciliation. We do have to leave the age of stupidity behind us.”

There are many question to be answered. First among them: are Ryan and his family willing to undertake a two-year front porch campaign? If so, a 10-term former congressman has a reasonable chance to win both the Democratic Party’s nomination, and the 2024 election itself.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

David Warsh: About ‘The Untold Story of Russiagate’

Trump campaign manager and pro-Russia operator at the 2016 Republican National Convention.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

In the summer of 2016, somebody, perhaps Vladimir Putin himself, sketched a peace plan for Ukraine. The provenance of the proposal remains deliberately vague. Had the suggestion been accepted, it would have avoided Russia’s war on its neighbor five years later. The so-called “Mariupol plan,” named for eastern Ukraine’s largest industrial city, would have split off four prosperous Donbass counties to form an autonomous republic, to be led by Viktor Yanukovych, the deposed president of Ukraine who had fled Kyiv for Russia two years before. In effect: East and West Ukraine

The trouble is, the proposal was conveyed, via intermediaries, amid elaborate secrecy, to just one man, U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump. Rival candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton, the former secretary of state, would certainly reject the plan were she to be elected. So the loosely worded proffer was said to be enhanced by a sweetener: Russia would take a hand in the American election, denigrating Clinton through a massive hacking campaign.

That’s the burden of a Sunday magazine article in Nov. 6 The New York Times Magazine: “The Untold Story of ‘Russiagate’ and the Road to War in Ukraine,” by reporter Jim Rutenberg. It is a long and complicated tale, and sticks closely the NYT’s editorial position: that Russia’s war was unprovoked by NATO expansion.

In fact, the story of the “Grand Havana Room meeting,” atop 666 Fifth Ave. in Manhattan, between Trump’s campaign manager, Paul Manafort , and Konstantin Kilimnik, manager of Manafort’s international consulting office in Kyiv, has been told before, though never as concisely as has Rutenberg: by the Mueller Report on Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election, the thousand-page Senate Intelligence Committee report, and by The Atlantic’s George Packer in his review of Andrew Weissmann’s book about his service as a top aide to former FBI director Robert Mueller, Where the Law Ends: Inside the Mueller Investigation.

Ruteberg drew on these accounts, and on his own reporting, in a mostly successful attempt to connect two narratives. “Thrumming below the whole (U.S.) election saga was another story – about Ukraine’s efforts to establish a modern democracy….”

From the platform battles of the Republican National Convention to the turmoil of the transition to the first impeachment, the main business of the Trump presidency all had to do with Ukraine. “Even now” he writes, “some influential voices in American politics, mostly but not entirely on the right, are suggesting that Ukraine make concessions of sovereignty similar to those contained in Kilimnik’s plan, which the nation’s leaders categorically reject.”

I was especially struck when I came across this passage:

As [Paul] Manafort rose to become Trump’s campaign chairman – and as Russian operatives were hacking Democratic Party servers – the candidate took stances on the region that were advantageous to Putin’s ambitions for Ukraine. Ahead of the Republican National Convention in Cleveland in July, Trump shocked the American foreign-policy establishment by voicing only tepid support for NATO. He also told aides that he didn’t believe it was worth risking “World War III” to defend Ukraine against Russia, according to the Senate intelligence report released in the summer of 2020.

That was, I thought, Trump in a nutshell. Candid, shrewd, perhaps even wise… and profoundly dishonest. After all, Manafort was a veteran political operative, who had served in the Reagan administration until leaving to form a foreign-relations consulting firm with his friend Roger Stone. He had been deeply involved in Ukrainian politics, mostly with pro-Russian factions, for more than a decade. What in the world was he doing suddenly showing up as Trump’s campaign manager barely two months before the election?

Three weeks after the convention, Manafort was forced to resign, after his name turned up on a suspicious Ukrainian payroll ledger. Starting in 2017, he was charged with multiple felonies, and convicted of many of them, Trump pardoned him in December 2020.

Rutenberg’s story reinforced my conviction that the endless harping of the editorial pages of The Wall Street Journal on “the Steele dossier” and Special Counsel John Durham’s lengthy investigation of FBI methods in dealing with it were red herrings of the first order. The investigations that began even before Trump took office had almost nothing to do with the discredited campaign documents. The various probes were motivated by suspicions of extensive conflicts of interest, and the fact that his campaign and presidency were chock-full of persons who had done business with Russia.

It matters because, not for the only time, Trump’s political instincts were canny, reflecting the unarticulated preferences of many American voters, perhaps a majority, to live in a peaceful, if imperfect world. Had Trump been able to do a deal with Putin along the lines of the Mariupol plan, many Ukrainian and Russian lives would have been saved. Trump almost certainly would have been re-elected, American democracy would have been further damaged, perhaps irreparably. Things turned out as they should have, at least until Russia invaded Ukraine. .

That is emphatically not to say that peace negotiations shouldn’t be pursued in this dreadful war. Republican opposition to continuing high levels of aid to Ukraine is growing, according to recent polls. Fifty-seven Republican congressmen and eleven senators voted against Biden’s $40 billion aid package earlier this year. New positions in both parties will take shape after the mid-term elections.

Meanwhile, Axios reports that Trump is eager to announce a third run for the presidency. Bring it on! American democracy learned a great deal about its weaknesses and strengths during the five years it was enrolled in Trump University. The experience produced a close call, but dangerous times make for lasting lessons. Two or three years of post-graduate education will produce still more insight into the inner workings of a strong democracy.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: Will the GOP abandonUkraine soon after the mid-term election?

— Map by Viewsridge

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Only a few days before an election is no time to be a columnist. This column is written some distance from Washington, D.C., but Edward Luce, of the Financial Times, is there in the thick of things. On Oct. 29, in “America’s Brittle Consensus on Ukraine,’’ he wrote “In the Republican quest to make a scorched earth of Biden’s presidency nothing will be sacred, including Ukraine’s military pipeline.” The “pro-Putin wing” of the GOP is still a minority, Luce added, but “almost every Republican will back {likely next House Speaker Kevin} McCarthy’s likely effort to impeach Biden and hold the U.S. debt ceiling hostage to their demands.”

That much, at least, remains to be seen. The presumptive speaker will settle on his plans only after the election results are known and thoroughly construed. Until then there remains a possibility that McCarthy’s Trump-based agenda will dissipate in a mood of grudging forgiveness following what may turn out to be a nobody-knows-anything election.

“The fact remains, however, that fifty-seven House Republicans and eleven senators voted against Biden’s $40 billion Ukraine aid package earlier this year. And though it hasn’t yet sunk in, Russian president Vladimir Putin took an active hand in the US election Thursday when, in an important speech, he asserted there were

“[T]wo Wests – at least two and maybe more but two at least – the West of traditional, primarily Christian values, freedom, patriotism, great culture and now Islamic values as well – a substantial part of the population in many Western countries follows Islam. This West is close to us in some things. We share with it common, even ancient roots. But there is also a different West – aggressive, cosmopolitan, and neocolonial… a tool of neoliberal elites [embracing what I believe are strange and trendy ideas like dozens of genders or gay pride parades].’’

He might as well have identified them as being, in his view, Republicans and Democrats.

Putin believes this is the basis for his war on Ukraine. It may be MAGA’s view as well. I don’t believe it is McCarthy’s. It certainly is not mine. But it will take time to work out the distinction. Less than a week before a very important election is no time to try.

Meanwhile, I’ve been been reading Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate (Yale, 2021), by M.E. Sarotte; Macroeconomic Policies for Wartime Ukraine (Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2022), by Kenneth Rogoff, Maurice Obstfeld, and seven others; “Warfare without the State,’’ Adam Tooze’s recent criticism of the CEPR plan; and “Russia’s Crimea Disconnect’’, by Yale historian Timothy Snyder; and Johnson’s Russia List, more or less daily.

Halloween was scarier than usual this year.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: The WSJ ‘contains multitudes’

On Chicago’s Lakefront.

— Photo by Alanscottwalker

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

A headline on a story Oct. 21 in the in The Wall Street Journal revealed “Chicago’s Best-Kept Secret: It’s a Salmon Fishing Paradise; Locals crowd into inlets off Lake Michigan to catch fish imported from West Coast to counter effects of invasive species.”

Between vignettes of jubilant fishermen braving the lake-front weather, reporter Joe Barrett offered a concise account of how Great Lakes wildlife managers have coped with successive waves of invasive species over eighty years of globalization. In the beginning were native lake trout, apex predators thriving on shoals of perch. Sea lampreys arrived in the Forties, through the Welland Canal, which connects Lake Ontario with Lake Erie. The blood-sucking eels devastated the trout population, while alewives, another invasive species, grew disproportionately large with no other to prey on them.

Authorities controlled the lampreys with a new pesticide in the mid-Sixties, and imported Coho and later Chinook salmon from the West Coast to rejuvenate sport fishing. Fingerling salmon hatched in downstate Illinois nurseries were released in Chicago harbors, to return to the same waters to spawn at maturity. Meanwhile, ubiquitous European mussels, released from ballast tanks of ships entering the lakes via the St. Lawrence Seaway, improved water clarity, but consumed nutrients needed by small fish. As a native of the region, I remember every wave.

A Coho salmon.

I was struck by the artful sourcing of Barrett’s story. He quoted fishermen Andre Brown, “a 51-year-old electrician from Oak Park;” Martin Arriaga, “a 59-year-old truck driver from the city’s Chinatown neighborhood,” and Blas Escobedo, 56, “a carpet installer from the Humboldt Park neighborhood.”

Providing the narrative were Vic Santucci, Lake Michigan program manager for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, and Sergiusz Jakob Czesny, director of the Lake Michigan Biological Station of the Illinois Natural History Survey and the Prairie Research Institute. The Illinois Department of Health chimed in with its recommendation: PCB concentration in the bigger fish meant no more than one meal a month.

Barrett did not mention the dangerous jumping Asia carp that now threaten to enter Lake Michigan; nor the armadillos, creeping north from Texas into Illinois, with global warming: much less the escalating crime rates in Chicago, which have McDonald’s threatening to move out of the city. But then his was a story about fishery management. And that’s what I like about the WSJ: it contains multitudes.

Earlier last week I had sought to convey to visiting friends the different sensibilities among the newspapers I read. I prize The New York Times for any number of reasons, but its concern for the future of democracy in America often seems overwrought. I look to The Washington Post for editorial balance (never mind the “Democracy Dies in Darkness” motto), and to the Financial Times for sophistication. But it is hard to exaggerate how much I enjoy The Wall Street Journal. I worked there for a time years ago; that surely has something to do with it. But I think it is the receptivity of its news pages I so admire. Like Joe Barrett’s fish story, its sentiments are inclusive. Read it if you have time.

Despites its sale to conservative newspaper baron Rupert Murdoch, the WSJ has preserved the separation between sensible news pages, its worldly cultural and lifestyle coverage, and its fractious editorial pages. Those editorial pages are still recovering from their enthusiasm for Donald Trump, and I sometimes think as I read them that they pose a threat to democracy, if only by their preference for derision. But still I read them, so they must be doing something right.

Barely two weeks remain before the mid-term elections. The races that interest me most are those seeking common ground: Ohio, Alaska, Pennsylvania, and Oregon. There will be time afterwards to sift the results. Is American democracy in danger? I doubt it. E pluribus unum! with a certain amount of thoughtful guidance along the way.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: The arduous advance of economics as seen through Nobel prizes

The Nobel Prize in Economics committee took note about this famed film, which revolves around a local banking crisis in The Great Depression.

STOCKHOLM

Eight economists have received invitations to Stockholm in December, three of them living, five of them dead. Three will show up, to accept their Nobel Memorial Prizes in the Economic Sciences. The five Spirits summoned, all but one laureates themselves, are still teaching, though only as textbook legends. A sixth Specter, significant to the story, did not make the list. He died in 2018.

Ben Bernanke, an applied economist who gradually became a central banker, and theorists Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig, who remained university professors for forty years, were recognized last week for two particular papers about banking and financial crises they wrote in 1983

“Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance and Liquidity,” by Diamond and Dybvig, in the Journal of Political Economy; and “Nonmonetary effects of the financial crisis in the propagation of the Great Depression,” by Bernanke, in the American Economic Review, were the only the first statements of the problems on which they intended to work. Many other technical papers followed, at first by the authors themselves, then by members of growing community of fellow-researchers determined to extend the boundaries of the field.

Neither of those first two papers settled anything. Together, however, they announced research projects that constituted “discoveries,” in the language of the citation, which, in the course of time, and in combination with the insights of many others, “improved how society deals with financial crises” – a key condition of many Nobel Foundation economics prize.

How? By demonstrating to a new generation of researchers how to approach exploring the previously uncharted territory of “financial intermediation,’’ meaning the operations of the institutions that occupied the larges space between two well-established regions: Keynesian macroeconomics, and its preoccupation with business cycles; and “monetarism,” a somewhat old-time fascination with the history and theory of money and banking.

In other words, this year’s prize recognizing the financial macroeconomics that has begun to emerge like a new textbook chapter from the void is more rhetorically powerful than it seemed, at least in the course of the usual show-business ceremony with which the prize was announced Oct. 10.

A 72-page essay on the scientific background of the award spelled out the story for those with the curiosity and patience to read. It tells a story of how economics makes progress: one generation of economists feasts on the glory of another. That is, newcomers to the discipline supplant one source of excitement with another. In this case, the new excitement arrived just in time.

. xxx

From the very beginning of their modern science, in the 18th Century, the background citation asserts, economists were well aware of the existence and nature of banks, of course. David Hume and Adam Smith were well aware of how bankers took deposits and then extended much more credit than the cash reserve they kept in the till. Hume and Smith knew all about the panics that regularly occurred when all the depositors wanted their money back at the same time. (The long Nobel citation mentions the Frank Capra movie, It’s a Wonderful Life.) Smith reasoned that free competition among banks would solve the problem, as long as lenders were prudent and followed the “real bills” rule.

During the 19th Century, economists mostly left the discussion of banks to bankers (Henry Thornton) and journalists (Walter Bagehot) while they worked on the problems of supply and demand that they cared about most. What they called “general equilibrium theory” emerged. Only in 1888 did the pioneering mathematical economist and statistician Francis Ysidro Edgework construct the first model of fractional banking.

Fast forward to the years after World War II, when economists began to write much more in mathematics instead of natural language, the better to be clearer among themselves. The ramifications of competition gradually became clear by formally modeling it as though it were perfect. And the first major payoff of mathematical language was the discovery that, at least in some important ways, everyday competition definitely wasn’t perfect. A model of monopolistic competition had emerged in the 1930s, a little too early for the Nobel Committee to take note of it; the first economics prize wasn’t given until 1969. Meanwhile, banking, whatever it was, remained the business of bankers.

In the 1970s, a significant part of the excitement in mainstream economics had to do with something called the Modigliani-Miller theorem. The authors, Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller, had met in the 1950s as colleagues at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh. In 1958 they agreed to teach a course in corporate finance in the business school there. What emerged was what Peter Bernstein, in Capital Ideas, The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street (1992), called “the bombshell assertion.” This was the proposition that, thanks to the principle of arbitrage, the ratio of debt to equity in a firm’s capital structure didn’t matter; Under perfect competition, in the absence of frictions and asymmetries of all sorts, no matter how the firm was financed, the enterprise value of the firm would be the same.

Enter financier Michael Milken, who in the 1970s pioneered modern high-yield (“junk”) bonds. Soon the debt-based restructuring takeover boom of the 1980s was underway. Modigliani was recognized in 1985 by the Nobel Committee “for his pioneering studies of savings and financial markets.” Five years later, Miller shared the prize with two other pioneers in finance for, in his case, his collaboration with Modigliani on the article “The Cost of Capital, Corporate Finance and the Theory of Investment.”

It was amid this commotion that the situation arose in which Diamond and Dybvig took up their challenge. Many banks in the 1980s were large and ubiquitous around the world, and enormously profitable. But why did they exist at all? In 1980, the author of one survey of the literature on banking stated: “There exist a number of rival models and approaches which have not yet been forged together to form a coherent, unified and generally accepted theory of bank behavior.”

Diamond and Dybvig did just that, according to the citation, offering two critical insights in the process. There were “fundamental reasons why bank loans are a dominant source of financing in the economy” for one thing, and “for why banks are funded by short-term, demandable debt.” For another, that meant that “banks are inherently fragile and thus subject to runs.”

. xxx

Bernanke approached the problem of financial intermediation from a different direction – from curiosity about the mechanisms of business cycles characteristic of the Keynesian macroeconomics that he studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dale Jorgenson had been Bernanke’s adviser at Harvard College. Stanley Fischer supervised his dissertation, along with Rudiger Dornbusch and Robert Solow. He finished “Long-term commitments, dynamic optimization, and the business cycle” in 1979 and took a job at Stanford University.

As the Nobel citation puts it:

“The dominant explanation at the time for why the Great Depression was so deep and prolonged was due to Milton Friedman and his wife, Anna Schwartz (1963). They argued that the waves of banking crises in 1930–1933 substantially reduced the money supply and the money multiplier. The failure of the Fed to offset this decline in money supply in turn led to deflation and a contraction in economic activity.’’

Friedman had moved from Chicago to San Francisco, where he taught part-time at nearby Stanford. There was not much other than traditional money and banking in A Monetary History of the United States, by Friedman and Schwartz, The citation continues,

Bernanke (1983) proposed a new (and in his view complementary) explanation of why the financial crisis affected output. According to this view, the services that the financial intermediation sector provides, including “nontrivial market-making and information gathering,” are crucial for connecting lenders to borrowers. The bank failures of 1930–1933 hampered the financial sector’s ability to perform these services, resulting in an increase in the real costs of intermediation. Consequently, borrowers – particularly households, farmers and small businesses – found credit to be expensive or unavailable, which had a prolonged negative effect on aggregate demand. Bernanke combines examination of historical sources, statistical analysis, and (at the time) recent theoretical insights to build this argument.

The lingering controversy between Keynesians and monetarists persists even today – about the cause, length, and depths of the Great Depression – was it the result of bad monetary policy carried out by the Federal Reserve Board in the United States, according to Friedman, or the outcome a worldwide series of accidents dating from World War I, in MIT’s Paul Samuelson’s view?

The citation states:

“To be clear, Bernanke’s analysis does not engage in the discussion of what caused the initial economic downturn in the late 1920s that subsequently escalated into the Great Depression, and this was not the focus of Friedman and Schwartz either. Similarly, when we discuss the Great Recession below, the core issue is not about its origins but on the mechanisms by which the recession played out.’’

Whatever the case, though, Bernanke stated his own view when, in 2002, in an important speech as a governor of the Fed at a celebration for Friedman’s 90th birthday, he concluded:

“Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.”

The citation, however, sticks to what happened in 1983:

“From the perspective of the contributions by Diamond and Dybvig, Bernanke’s work can be seen as providing evidence supporting their models. Specifically, he provides evidence that bank runs can lead to financial crises (as in Diamond and Dybvig, 1983), which in turn leads to prolonged periods of disruption of credit intermediation, consistent with bank failures destroying the valuable screening and monitoring services banks perform (as in Diamond, 1984).’’

Thus the guest list for this year’s prize celebration includes Bernanke, Diamond and Dybvig. Perhaps the authorities will find a seat as well for Stanley Fischer, former president of the Bank of Israel. But the honored ghosts whose earlier work the three displaced will be present as well: Modigliani and Miller; Samuelson, Friedman and Anna Schwartz, Only Dr. Schwartz failed to receive the ultimate diploma, but then the centrality of A Monetary History was not yet apparent in 1976, neither was the extent of her contribution to it, when Friedman received his prize.

As for what happened in 2008, the prize citation has nothing to say. Wall Street Journal columnist Greg Ip noted that “Outside of a footnote, the committee managed to ignore Mr. Bernanke’s central role in responding to that crisis.’’ The Swedes chose to tell the story from its beginning, instead of its end. What, then, did we learn from the 2008 crisis? We’ll have to wait a little longer for that prize.

Meanwhile, what about that sixth Specter, the uninvited guest at the banquet?

That would be Martin Shubik, of Yale University, a long-time player in the Nobel nomination-league, who supervised both Diamond and Dybvig in their graduate studies. Shubik himself had worked, for a dozen years without conspicuous success, on the more forbidding problem of integrating the production of money and banking into the market system Not long before he died, he believed he had solved it. A paperback edition of (2016), with Eric Smith, appears next month.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville, Mass.-based economicprincipals.com.

David Warsh: Exploring ‘quantum weirdness’

Main building of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, in Stockholm.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I spent its time last week reading up quantum entanglement. Instantaneous connections between far-apart locations – the possibility of “spooky action at a distance” that was dismissed by Einstein – turns out to have become the basis of quantum computing and fail-safe cryptography.

First I read The New York Times story: Nobel Prize in Physics Is Awarded to 3 Scientists for Work Exploring Quantum Weirdness. by Isabella Kwai, Cora Engelbrecht and Dennis Overbye. I especially liked the part about John Clauser’s duct-tape and spare-parts experiment in a basement at the University of California at Berkeley that opened the laureates’ path to the prize. (Stories in The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times each had distinctive strong points as well.)

The Times story led me back to MIT physicist/historian David Kaiser and his 2011 book, How the Hippies Saved Physics: Science, Counterculture, and the Quantum Revival. I didn’t read it when it appeared, having a mild prejudice against hot tubs, psychedelic drugs and saffron robes. I was wrong. I ordered a copy last week.

Next was a Science magazine piece from 2018 by Gabriel Popkin that showed the discoveries well on their way to acceptance: Einstein’s ‘spooky action at a distance’ spotted in objects almost big enough to see.

Then came a Scientific American article, The Universe Is Not Locally Real, and the Physics Nobel Prize Winners Proved It, by David Garisto, that seemed to me to offer the most lucid explanations of the profound uncertainties involved. These are more daunting than ever in the face of irresistible technological evidence that they exist.

At that point I returned to the Nobel announcement, and skimmed the citations in the scientific background to see if the story was as I had been taught (by my mother, Annis Meade Warsh, who was herself entangled with science and religion!). Sure enough there among the citations was the history of the argument, from Erwin Schrödinger, in 1935; to Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen, in 1935; to David Bohm, in 1951; to John Stewart Bell, in 1964; and to Stuart Freedman and Clauser (the former having been Clauser’s graduate student), in 1972. Imagine my surprise last year when I discovered the distinguished historian of physics John Heilbron was reading Bohm’s last book, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, the very title recommended to me by my mother not long after its publication, in 1980. I checked Wholeness out from the library. I could not fathom the implicated order.