Frank Carini: In search of old-growth forests

An old beech tree in the Rhode Island woods.

— Photo by Frank Carini

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

WARWICK, R.I. — Last winter Nathan Cornell accidentally found himself “walking into a different world,” one that isn’t protected from human intervention. For the past two years, the University of Rhode Island graduate has been searching for old-growth forests in Rhode Island.

He found one not far from his Warwick home.

His hunt for old-growth forests led him and Rachel Briggs to found the Rhode Island Old Growth Tree Society, a nonprofit determined to locate, document, map and advocate for the preservation of all remaining old-growth and emerging old-growth trees and forests in the state. This means trees and groups of trees that are 100 years old and older.

Cornell, with the help of licensed arborist Matthew Largess, owner of Largess Forestry, in North Kingstown, R.I. has so far identified more than a dozen potential old-growth pockets, including on the University of Rhode Island campus in South Kingstown and in Cranston, North Kingstown, Portsmouth, Warwick and West Greenwich.

In mid-July, the 24-year-old took this ecoRI News reporter on a walking tour of the hidden-in-plain-sight “5- to 10-acre” Warwick property owned by the Community College of Rhode Island and Kent Hospital. To listen to the audio story, click the bar at the top.

Anyone interested in joining the Rhode Island Old Growth Tree Society, can contact Cornell at ncornell@my.uri.edu. To read an opinion piece written by Cornell and recently published on ecoRI News, click here.

Frank Carini is co-founder and a journalist at ecoRI News.

Tips for New England gardeners in drought

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

For backyard gardeners, mild droughts and water-ban restrictions common during the summer can be a cause for concern. Kate Venturini Hardesty, a program administrator and educator with the University of Rhode Island’s Cooperative Extension, offers some tips for gardeners who are feeling the heat.

Let your lawn rest.

“Your lawn is on summer vacation,” she said. “Lawns are meant to go dormant in July and August. Many turf types are perennial species, so they rely on a break, much like the herbaceous perennials in our gardens. When we don’t allow them to rest, they’re weaker, just like you and I without a good night’s sleep. Refraining from watering the lawn saves a tremendous amount of water.”

While this may mean that your lawn is brown instead of a vibrant green, it will be beneficial for its overall health.

Don’t mow your lawn too low.

Mowing your lawn too far down will also have a negative impact on it. You don’t want to be the golf course of your neighborhood — the taller your grass is, the healthier it will be.

“The higher your mower is set, the deeper the roots are able to go underground to access soil moisture,” she said.

Water your crops and gardens as early in the day as possible.

“Don’t water any time but the morning,” she said. “It gives the plants some time to actually absorb the water before it evaporates.”

If you water at noon, you’ll lose a bunch of water to evaporation. If you water in the evening after the sun has set, you run the risk of causing fungal issues for your plants.

Know what plants are best for your garden.

When it comes to designing and planning your gardens and landscaping, it’s critical that you know which plants are the best suited for your space. Plants that are native to your area will generally do best because they evolved and are able to adapt to the way your local climate is changing on both the micro and macro levels.

The types of plants that are best to plant vary from garden to garden based on a variety of factors, including sun exposure, solid health, and drainage. Before you plant, do your research.

“A simple site assessment exercise can help you gather information about available sunlight and water, wind exposure, drainage and soil health,” she said. “The more information you have, the easier it is to choose plants that can tolerate the climate on your site.”

Venturini Hardesty said that, on average, New England tends to get about 45 inches of rain annually. If the average rain per week is about an inch, that leaves about seven weeks without rain, which happens to be almost the full length of the months of July and August.

The shifts that climate change will bring to backyard gardeners – and crop growing and planting as a whole – will need to be dealt with on a regional level, not in individual backyards, she said.

Cynthia Drummond: These clingers might send you to the ER

Clinging jellyfish

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

CHARLESTOWN, R.I. — Recent warnings about the presence of clinging jellyfish in some coastal ponds have caused a stir, because the tiny organisms sting, and they are difficult to spot.

People who use the ponds should be aware of the possibility they might encounter clinging jellyfish, or gonionemus vertens.

Katie Rodrigue, principal marine biologist with the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Marine Fisheries, has been monitoring clinging jellyfish, because while their sting is an unpleasant nuisance for most people, others may experience serious allergic reactions.

“The reason it’s a cause for concern is because, for some individuals, it can cause a severe sting,” she said. “In 2019, I believe it was, we had a couple of people end up in South County Hospital after being stung, because they had a pretty severe reaction to it.”

Clinging jellyfish have two life stages — a polyp and a medusa, which is produced by the polyp. The polyps, which are only about half a millimeter in size, are found in Rhode Island throughout the year and produce medusae in mid- to late summer. A single polyp will produce multiple medusae, and it is during this medusa stage that the organisms develop tentacles, and become jellyfish that sting.

“There’s two life stages of it, and the medusa stage is what we would recognize as the jellyfish — the bell with the tentacles,” Rodrigue said.

The clinging jellyfish is an invasive species that was first recorded on Cape Cod and in Groton, Conn., in the late 1800s. That population, which originated in the Eastern Pacific, declined as eelgrass beds died.

In the 1990s, clinging jellyfish began to make a comeback and are associated with a North Pacific species that produces more toxic stings.

How did this species get all the way to New England? Rodrigue said it could have made the trip as a polyp.

“Because that polyp stage can latch onto hard surfaces, it could have latched onto a ship’s hull,” she said. “I think one theory I read about was bringing oysters in. That could have brought in some of those polyps.”

What distinguishes clinging jellyfish is a reddish-brown “x” mark on the bell, but that marking doesn’t mean they are easy to detect.

“They’re really tough to see, especially during the day, and they get their name ‘clinging jellyfish’ because they like to hold on to eelgrass and other submerged vegetation,” Rodrigue said. “They sort of hide during the day and hang on, but if they get disturbed, say, if somebody’s walking through an eelgrass bed or something, they would release off of it and swim into the water column, and that’s when somebody would be able to encounter them.”

Clinging jellyfish have sticky tentacles, armed with cells with barbed structures called nematocysts, which contain venom.

“Those tentacles can kind of stick to your skin, and those nematocysts will fire,” Rodrigue said. “It’s almost like a tiny needle that penetrates the skin and it releases that venom into your skin, and that’s what causes the stinging sensation, and the tentacles have tons of nematocysts on them. Many jellyfish have this, and anemones, and other animals like that.”

Clinging jellyfish are active at night, hunting zooplankton.

“At night is when they’ll release themselves off of the eelgrass and then they’re in the water column, feeding on zooplankton,” Rodrigue said. “And so, they’ll be a little bit more mobile at night.”

So far this summer, clinging jellyfish have been recorded in Potter Pond in South Kingstown and parts of Ninigret Pond. In previous years, they have been documented in Point Judith Pond and the Narrow River. It’s important to keep in mind, however, that they could be living in other waterbodies and just haven’t been spotted yet.

Clinging jellyfish are not the only species that people should be watching for. Salt Ponds Coalition president Arthur Ganz, a retired marine biologist, said he had not been notified of any encounters with clinging jellyfish this summer and described the stinging sea nettle jellyfish as being far more numerous.

“Sea nettles are very abundant in the ponds, more so, I’m going to say, over the last 20 years,” Ganz said. “Their numbers have very much increased. We’d see them occasionally in the real hot summer, but now, they’re everywhere. I was out on my boat and I just looked down at my mooring and there was probably 20 within a square meter. So, they are the ones that are the biggest nuisance.”

More benign, non-stinging jellyfish species such as comb and moon jellies also inhabit the Ocean State’s coastal ponds.

“They don’t have obvious tentacles and they don’t bother people,” Ganz said. “It’s essentially the sea nettles that are the biggest problem.”

On the ocean side, beachgoers should steer clear of the cyanea, or lion’s mane jellyfish, which can grow to be very large and is armed with long, stinging tentacles.

“They’ll give you a nasty sting, and what happens with the cyanea is, on the ocean side, they’ll break up in the surf, so the tentacles are floating free, so even though you don’t have one right there in your vision, you could get nailed by the broken-up tentacles,” Rodrigue said.

She suggests people who plan to spend time in the calmer areas of the salt ponds, especially near eelgrass beds, wear protective clothing.

“If you’re going to be in one of these coastal-pond environments, an area that’s very calm and protected and has a lot of submerged vegetation, I suggest just covering up,” she said. “If there’s a barrier between the jellyfish and your skin, that’s going to be the best bet to avoid getting stung; waders, wet suit, even leggings will all help with that.”

People who are stung should apply plain, white vinegar to the affected area.

“What that’ll do is at least prevent any more stinging cells from firing,” Rodrigue said, adding that the old remedy of pouring urine on a sting is definitely not recommended.

“Do not do that,” she said. “If anything, that can actually make it worse. That, or using fresh water. A lot of people, because of the irritation, they might want to dump some cool, fresh water on it, but that’ll actually cause more stinging cells to fire on your skin.”

DEM asks people who encounter clinging jellyfish to contact the agency at 401-423-1923 or by email at DEM.MarineFisheries@dem.ri.gov. Reports can also be posted on Facebook or Instagram.

Cynthia Drummond is an ecoRI News contributor.

Frank Carini: Will federal reprieve be enough to save these very fast sharks?

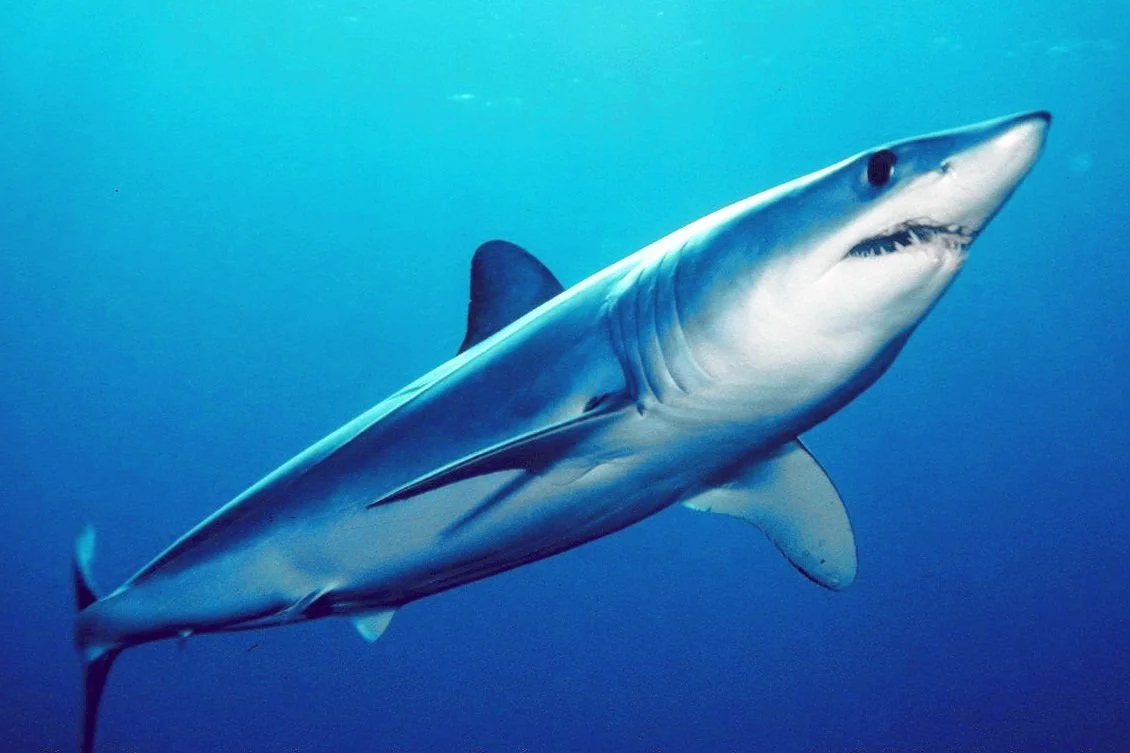

An Atlantic shortfin mako shark

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The world’s fastest-swimming shark is about to get a reprieve from overfishing.

Beginning July 5, the landing or possession of Atlantic shortfin mako sharks in the United States has been prohibited. This rule applies to commercial fishermen, recreational anglers and any dealers who buy or sell shark products. These sharks frequent southern New England waters.

The ban includes sharks that are dead or alive when captured, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries).

The recent decision has long been supported by shark-research organizations concerned about the significant issues that this species faces. Defenders of Wildlife and the Center for Biological Diversity sent a notice June 28 to Gina Raimondo, U.S. secretary of commerce, and Janet Coit, assistant administrator for NOAA Fisheries, of their intent to sue for failing to protect the shortfin mako shark under the Endangered Species Act.

“The shortfin mako shark is the world’s fastest-swimming shark, but it can’t outrace the threat of extinction,” Jane Davenport, a senior attorney at Defenders of Wildlife, is quoted in a press release about the organizations’ intent. “The government must follow the science and provide much-needed federal protections as quickly as possible. This will demonstrate America’s leadership in fisheries and ocean wildlife conservation both at home and on the world stage.”

The shortfin mako is a highly migratory species whose geographic range extends throughout the world’s tropical and temperate oceans. They can reach a top speed of 45 mph, and, like tunas and the white shark, shortfin mako sharks have a specialized blood vessel structure — called a countercurrent exchanger — that allows them to maintain a body temperature that is higher than the surrounding water. This adaptation provides them with a major advantage when hunting in cold water. As an apex predator, the species is an integral part of the marine food web.

The species, however, faces a barrage of threats, especially overfishing from targeted catch and bycatch. The species’ highly valued fins and meat incentivize this overexploitation.

“The shortfin mako shark has long been a target of commercial fisheries and consumers due to its excellent taste, and to sport fishermen for its spectacular strength and leaping ability,” said Jon Dodd, executive director of the Wakefield, R.I.-based Atlantic Shark Institute. “Unfortunately, those are the same issues that have resulted in the significant population decline of this iconic shark that required this complete and unprecedented closure.”

Dodd noted female mako sharks don’t reproduce until they are about 20 years old and weigh some 600 pounds.

“I’ve seen hundreds of mako sharks and exactly one that size in all my years researching this spectacular shark,” he said. “It’s amazing that they can even reach that age and size with all the fishing pressure and risks they face.”

Since mako sharks have few young, and they take time off between giving birth, Dodd said the numbers don’t favor their long-term survival without significant management changes.

Three years ago the International Union for Conservation of Nature classified the shortfin mako as “endangered” on its Red List of Threatened Species.

“The Fisheries Service failed to protect the shortfin mako despite an international scientific consensus that conservation action is urgently needed,” Alex Olivera, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, said in the June 28 press release that quoted Davenport. “Even as the rest of the world scrambles to save these sharks from extinction, they have no protections under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. That needs to change.”

On NOAA Fisheries’ species directory Web page for the shortfin mako shark, it reads: “U.S. wild-caught Atlantic shortfin mako shark is a smart seafood choice because it is sustainably managed and responsibly harvested under U.S. regulations.”

On the same page the federal agency notes that, according to the 2017 stock assessment, shortfin mako sharks are “overfished and subject to overfishing.”

In a 2019 assessment, the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) estimated that as much as 4,750 metric tons of mako shark were being taken on an annual basis.

“It was time to give the mako shark a break, but even so, we are still looking at a recovery that will take until 2070,” Dodd said. “This is not a quick fix by any means, and the mako still faces significant challenges.”

If ICCAT provides for U.S. harvest in the future, NOAA Fisheries could increase the shortfin mako shark retention limit, based on regulatory criteria and the amount of retention allowed by ICCAT. Until that happens, the retention limit will remain at zero, according to the agency.

Frank Carini is senior reporter and co-founder of ecoRI News.

Frank Carini: Working to reduce environmental impact of ocean racing sailboats

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

While the United States flails about trying to reduce its enormous share of world-altering climate pollution, one part of the transportation/recreational sector is routinely ignored: boating.

Yachting and sailing are steadily gaining in popularity, so an urgency to act is essential if greenhouse-gas emissions are to be significantly reduced.

Yes, sailing burns little fossil fuel, but the resources consumed to build some of these vessels is swelling.

For instance, over the past decade, the carbon footprint of 60-foot International Monohull Open Class Association (IMOCA) racing boats has grown by nearly two-thirds, from 340 to 550 tons — the equivalent of driving an average car 1.4 million miles, according to the 11th Hour Racing Team.

“This is an overall trend we see in pretty much any industry, driven by performance we have accelerated too fast in the wrong direction, and are only just waking up to reality,” according to Damian Foxall, sustainability program manager for the 11th Hour Racing Team. “The need to reduce our emissions in the marine industry is urgent — 50% by 2030, and that’s just eight years away. We are far away from that right now.”

The 11th Hour Racing Team is sponsored by 11th Hour Racing, a Newport, R.I.-based nonprofit that works with the sailing community and maritime industries to “advance solutions and practices that protect and restore the health of our ocean.”

Late last year the team published a report about the importance of building a more sustainable ocean racing boat and better understanding the industry’s environmental impact. It showed performance doesn’t need to be sacrificed to build a more environmentally friendly boat.

“Business as usual is no longer an option. While the performance sailing sector and much of the leisure marine industry is geographically centered in the global North and a few other well-off regions, we live in a fragile bubble of prosperity,” according to the report. “This alternative reality does not reflect either the reality for most of the world’s citizens, or the availability of the earth’s resources.

“Inherently tied to the ongoing growth of global economies, we would need 1.7 Earths each year just to maintain the situation for the average global citizen. Scaled to the typical lifestyles associated with the marine industry this is more like 5+ Earths each year: a growing annual debt,” the report says.

The 128-page report includes a detailed study of material life cycles and alternative composites, such as flax to replace ubiquitous virgin carbon fiber. About 80 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in a boat build are associated with the use of composite materials, most notably carbon fiber, which is perfect for racing because it is light and stiff. Reducing the use of this material and others would significantly lessen climate emissions tied to the building of a new racing boat, according to the 11th Hour Racing Team.

In fact, the 11th Hour Racing Team and its partners are advocating for radical change across the marine industry to transform the way boats are built. They believe that only by “prioritizing sustainability along with performance, can the marine industry take urgent action to fight climate change.”

Foxall recently told ecoRI News that sustainable sourcing and using as much renewable energy as possible are the two biggest things racing teams can do right now to lower their carbon footprints.

The 11th Hour Racing Team, for instance, now leases an electric support vessel during races, which has lowered climate emissions from both a transportation and manufacturing perspective.

Foxall said rule changes would require sailing teams to incorporate more sustainable materials into their design and build. He noted, for example, reused carbon fiber is mostly avoided because the virgin material makes for better performance. But if rules required every team to use recycled fiber, no team would have an advantage.

“In our sport, rules define what the boats are … as much as one team or a couple of teams or even an event might want to improve the footprints, that cannot happen until the rules incentivize it,” Foxall said. “And the rules for the longest time have incentivized performance, whether it is carrying more sacks of coal or corn from Australia to Europe or transporting more people from Europe to North America or now racing faster and going faster through the water. It’s all about performance.”

He added the sport can no longer “just make decisions based purely on performance. We need to be taking into account the direct and indirect impacts” on the environment.

The December report recommends establishing minimum standards on sourcing, energy, waste, and resource circularity; defining a threshold for carbon emissions based on life cycle assessment (LCA) data; incentivizing the marine industry to use its inherent capacity for innovation to focus on sustainability; and setting an internal price for carbon emissions.

Amy Munro, sustainability officer for the 11th Hour Racing Team, noted the building of a racing boat is a complex process involving a number of stakeholders, materials, and components.

“You need to break it down in detail to fully understand what are the major impacts,” according to Munro. “This is why we have meticulously measured the impact of every step in the design and build process of our new boat and conducted a life cycle analysis that helps to uncover underlying issues.”

Last month, Charlie Enright, 11th Hour Racing Team skipper, spoke at the U.N.-supported One Ocean Summit in Brest, France, to highlight key findings of the organization’s “Sustainable Design and Build Report,” notably the importance of industry-wide collaboration to push sustainable innovation to align with the Paris Agreement.

“Within our sport, for too long we have chased performance over a responsibility for the environment and people,” the Bristol, R.I., native told an audience of experts, politicians, activists, and decision-makers. “We must work together to reduce the impact of boat builds, adopt the use of alternative materials like bio-resins and recycled carbon, lobby for a change to class and event rules to reward sustainable innovations, and support races and events that are managed with a positive impact on our planet and people.”

Foxall noted about 50 percent of sailors are onboard when it comes to making their sport more sustainable. He said it is their responsibility to bring the others up to speed about the impacts of the climate crisis.

In an email to ecoRI News, Enright noted the sport’s awareness of climate and environmental issues is “definitely increasing.” He said big events such as The Ocean Race and the Transat Jacques Vabre have “strong sustainability policies” in place, including plastic-free race villages, onboard waste calculation initiatives, and efforts to educate teams and fans about these matters. “This is relatively new in our sport.”

The Ocean Race also runs an ocean science program in partnership with 11th Hour Racing, collecting data on water temperature, salinity, and other potential climate change impacts. The Transat Jacques Vabre uses the 11th Hour Racing Team’s Sustainability Toolbox, which, among other things, commits to efforts to limit waste, use renewable energy and reduce emissions wherever possible, as a framework for its own sustainability program.

“Of course there are those who need a bit more convincing on the importance of it,” Foxall said. “But, quite frankly … kids coming home from school today know what the issue is.”

In 2019, greenhouse-gas emissions from ships and boats in the United States alone totaled 40.4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. Globally, bulk carriers are the main source of shipping/boating climate emissions. Some 90 percent of world trade is carried across the world’s oceans by some 90,000 marine vessels. Carbon dioxide emissions from these vessels are largely unregulated.

Last year, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) did adopt exhaust emission standards for marine diesel engines installed in a variety of marine vessels, ranging in size and application from small recreational boats to large ocean-going ships.

While the shipping industry is responsible for a significant proportion of global climate emissions — if global shipping were a country, it would be the sixth-largest producer of greenhouse gases behind China, the U.S., Russia, India and Japan — the climate impacts of the recreational powerboat industry, most notably yachts, are considerable.

The propulsion systems on many yachts are arguably the least-efficient modes of transportation ever devised. The typical 40- to 50-foot yacht guzzles fuel.

U.S. recreational boaters spend about 500 million hours annually cruising fresh and salt waters. In 2010, more stringent EPA emissions standards for marine engines, both in-board and outboard, went into effect. But, unlike cars, private boats are not inspected. They can be checked by the Coast Guard or law enforcement, but there is no annual emissions check.

Many recreational boats and some jet-propelled watercraft have two-stroke engines. Conventional two-stroke engines produce about 14 times as much climate pollution as four-stroke engines.

Last year new U.S. powerboat sales surpassed 300,000 units for the second consecutive year, closing 2021 about 6 percent below record highs in 2020 and some 7 percent above the five-year sales average, according to the National Marine Manufacturers Association. In 2020, annual U.S. sales of boats, marine products and services totaled $49.3 billion, up 14 percent from 2019.

The oceans play an essential role in keeping atmospheric carbon dioxide in balance by absorbing about 30 percent of the CO2 that is released, from all sources. This blue carbon sink, however, has been working overtime since the Industrial Revolution began belching fossil fuels into the atmosphere.

The ocean, though, can only swallow so much of this colorless gas. When carbon dioxide is absorbed by seawater, chemical reactions occur that increase the acidity of the water through a process known as ocean acidification.

Acidifying marine waters are bad news for marine life with calcium carbonate in their shells or skeletons, such as oysters, corals, crabs, scallops, and mussels. Studies have found that more acidic salt waters make it more difficult for them to develop their hardened protection.

As of early last month, the recorded amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was a tick away from 418 parts per million (ppm) — well beyond the 350 ppm that climate scientists have deemed safe for humans, never mind most of the planet’s other living inhabitants.

“While the situation is extremely urgent and ‘business-as-usual’ is clearly no longer an option, it is still technically possible to close your eyes and look away,” Enright wrote. “This is why we have to act now and we have to create our own pressure. What we need is a radical change and one of the most important parts here is that the marine industry works together to achieve it.”

Frank Carini is co-founder and senior reporter of ecoRI News.

Azzam, at 592.5 feet, was the longest superyacht, as of 2020.

— Photo by ChrisKarsten

Frank Carini: Valiantly fighting epidemic of shoreline trash

During a single day in May 2019, Geoff Dennis and trusted sidekick Koda collected 282 balloons from the Little Compton, R.I., coastline. It was the duo’s largest balloon haul.

— Courtesy photos

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The mission is simple but the work is aggravating, especially since Geoff Dennis’ four-legged buddy no longer joins him on the almost-daily treks. Also, he doesn’t get paid.

For the past decade, the Little Compton, R.I., resident has been picking up other people’s trash that accumulates along the local shoreline. Between 2012 and 2020, Dennis picked up 35,607 pieces of litter from the banks of the Sakonnet River, at Goosewing Beach Preserve and a few other places. The vast majority of it was some form of plastic, from bottles to spent shotgun shells.

Despite “still missing my boy Koda” — his trusted black Lab died two days after Christmas 2020 at the age of 14 — the longtime quahogger and bird photographer remains a one-person cleanup crew.

“I miss him as much today as that last day with him,” Dennis said.

His immersion into litter began in 2012 while monitoring piping plovers at Goosewing Beach for The Nature Conservancy. The amount of plastic debris at his feet disgusted him.

When he returned, he picked up more than 100 Mylar balloons from the area. He’s been picking up coastline trash ever since. He’s bothered that 10 years later, most people still don’t seem to care about the state’s growing plastic problem.

Dennis said graduation time brings the greatest number of depleted balloons. July and August are the height of trash collection.

He recently tallied up his 2021 trash scorecard. Here is the breakdown:

Mylar balloons: 1,388.

Plastic bottles and aluminum cans: 1,349. He said year-end totals do not include old plastic bottles that have “become eggshell brittle and started the process of fragmenting. They go directly to trash.”

Plastic bottle caps: 1,209.

Latex balloons: 780. He said latex balloons are usually only the mouth piece, or ring piece, with attached ribbon. “I do find shredded pieces of latex too, but tally only the ring. Sometimes difficult to count when it may be a 30-plus mass of rings and tangled ribbon.”

Plastic straws: 328.

Spent plastic shotgun shells: 302.

Nips: 195.

Rubber gloves: 164.

Plastic and foam cups: 132. He said Dunkin’ Donuts (67) and Cumberland Farms (38) cups are the most common. “CF is still using foam cups and all found are foam. DD ceased using foam in 2020. Plenty of their paper cups were collected but are not in the tally.”

Golf balls: 119.

Plastic lids for plastic and foam cups: 104.

Plastic wads for shotgun shells: 86.

Plastic bags: 66.

Plastic cigarette lighters: 50.

Plastic K-cups: 45.

Since Dennis returned to Goosewing Beach 10 years ago to pick up Mylar balloons, there are 41,924 fewer pieces of litter along the Little Compton shoreline.

A trio of bills has been introduced during the current General Assembly session to address the Ocean State’s plastic pollution problem, including legislation to ban the sale of nips.

Frank Carini is senior reporter and co-founder of ecoRI News.

The Benjamin Family Environmental Center at the Goosewing Beach Preserve

The Sakonnet River as viewed from Portsmouth, R.I., looking south towards the ocean.

Roger Warburton: Nearby ocean warming a climate-change warning for New England

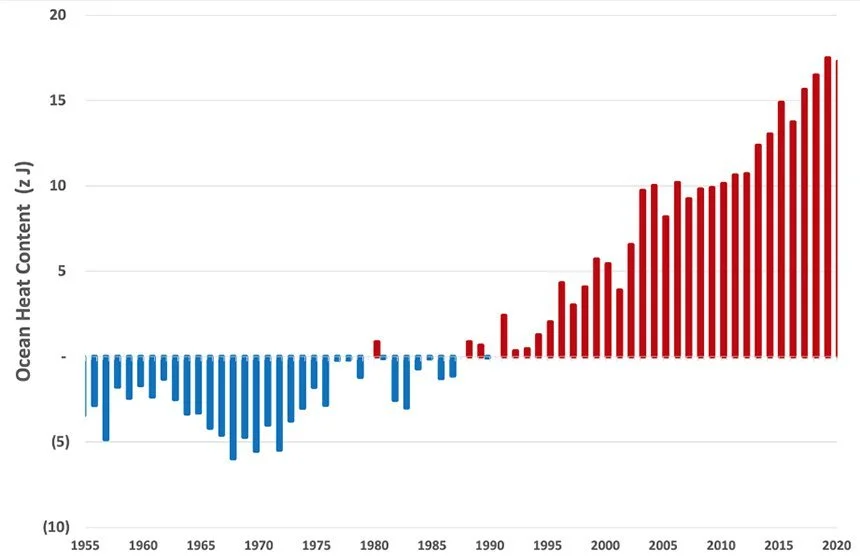

The changes in heat content of the top 700 meters of the world’s oceans between 1955 and 2020.

— Chart by Roger Warburton/NCEI and NOAA

New England’s historical and cultural identity is inextricably linked to the ocean that laps at nearly 6,200 miles of coastline. And the region’s ocean waters are warming, and not just a little.

The above chart shows just how much the ocean has warmed over the past 65 years and, due to the accumulation of greenhouse gases, the heat dumped into the ocean has doubled since 1993. It is even more concerning that ocean warming has accelerated since 2010.

The world’s oceans, in 2021, were the hottest ever recorded by humans.

The findings of the data from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), which is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), have been confirmed by Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, China’s Institute of Atmospheric Physics, and the Japan Meteorological Agency’s Meteorological Research Institute.

The news for New England is worse, as the ocean here is heating up faster than that of the rest of the world.

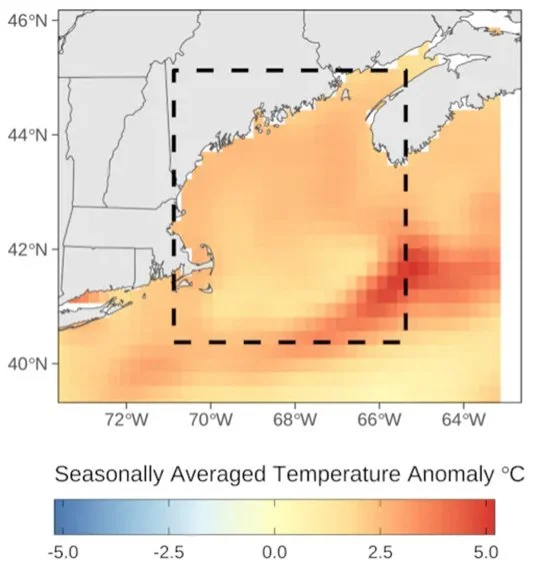

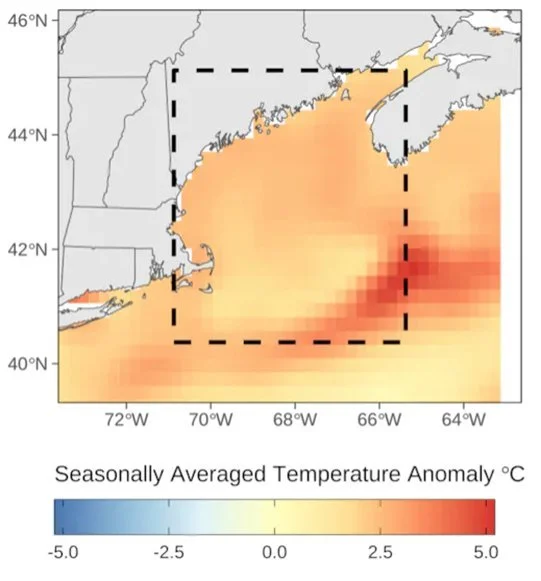

This map illustrates the seasonally averaged sea-surface temperature anomaly in the Gulf of Maine.

—Gulf of Maine Research Institute

The Gulf of Maine Research Institute announced that between September and November of last year, the warmth of inlet waters adjacent to Maine and northern Massachusetts was the highest on record.

“This year [the Gulf of Maine] was exceptionally warm,” said Kathy Mills, who runs the Integrated Systems Ecology laboratory at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute. “I was very surprised.”

The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than 96 percent of the world’s oceans, increasing at a rate of 0.1 degrees Celsius (0.18 degrees Fahrenheit) annually over the past four decades.

The increased concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere traps heat in the air. The air in contact with the ocean transfers heat to the ocean, increasing what is called the ocean heat content (OHC).

The first measurements of ocean data were taken on Capt. James Cook’s second voyage (1772-1775). Although not very accurate, those measurements were among the first instances of oceanographic data recorded and preserved.

Today, ocean measurements are taken by a variety of modern instruments deployed from ships, airplanes, satellites and, more recently, underwater robots. A 2013 study by John Abraham, a professor at the University of St. Thomas, contains an interesting historical overview of ocean measurements.

Abraham’s study used data from new instruments, such as expendable bathythermographs and Argo floats. The Argo program is an array of more than 3,000 autonomous floats that return oceanic climate data and has advanced the breadth, quality and distribution of oceanographic data.

As heat accumulates in the Earth’s oceans, they expand in volume, making this expansion one of the largest contributors to sea-level rise.

Although concentrations of greenhouse gases have risen steadily, the change in ocean-heat content varies from year to year, as the chart above shows. Year-to-year changes are influenced by events, such as volcanic eruptions and recurring patterns such as El Niño. In fact, in the chart one can detect short-term cooling from major volcanic eruptions of Mounts Agung (1963), El Chichón (1982) and Pinatubo (1991).

The ocean’s temperature plays an important role in the Earth’s climate crisis because heat from ocean surface waters provides energy for storms and influences weather patterns.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport, R.I., resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

References: Cheng, L. J, and Coauthors, 2022, “Another record: Ocean warming continues through 2021 despite La Niña conditions. Adv. Atmos. Sci., https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-1461-3.

Abraham, J. P., et al. (2013), “A review of global ocean temperature observations: Implications for ocean heat content estimates and climate change,” Rev. Geophys.,51, 450–483, https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/rog.20022.

Cynthia Hammond: Does Conn.-R.I. Amtrak bypass plan still live?

Amtrak Acela train near Old Saybrook, Conn.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

CHARLESTOWN, R.I.

A U.S. Department of Transportation “Providence to New Haven Capacity Planning Study” has some local officials wondering whether the original plan to run train tracks through sections of their town, and other Rhode Island and Connecticut towns, might not be dead after all.

The study is part of the Northeast Corridor 2035 Plan, or “C35,” a 15-year plan to guide investment in rail service in the Northeast.

The C35 describes the plan, which has an estimated cost of $130 billion, as the first phase of the long-term vision for the corridor described in the Federal Railroad Administration’s 2017 NEC Future plan, which includes “making significant improvements to NEC rail service for both existing and new riders, on both commuter rail systems and Amtrak.”

In 2016, Charlestown officials learned, by chance, that the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) had released its Tier 1 environmental impact statement (EIS) on a plan to straighten train tracks in the Northeast to accommodate high-speed rail service. The plan wasn’t met with broad enthusiasm.

The FRA had sent letters to affected towns and the Narragansett Indian Tribe in 2015, soliciting comments on the draft EIS, but according to a blog post on the plan by the Charlestown Citizens Alliance political action committee, there was no specific mention of new tracks going through Charlestown or other neighboring towns.

"Most of these governments have no recollection of receiving communication from the FRA,” the post read. “The letter does not say that new rails and a new rail route are proposed in your community. When no comments came from one of the most impacted towns, this should have suggested to the FRA that the local community and local stakeholders were not aware and engaged in the review process.”

The unpleasant surprise included in the plan was the Old Saybrook to Kenyon Bypass, which would have moved rail traffic directly through Old Saybrook, Conn., Westerly and Charlestown, bisecting neighborhoods, nature preserves and historic farms. The towns and Narragansett Indian Tribal officials fought the plan, and the Record of Decision, released in 2017, omitted the bypass.

But the omission didn’t mean that the bypass had simply gone away, and the Charlestown Citizens Alliance warned that the decision left the door open to a study which could resurrect the bypass.

The alliance’s blog post published after the decision reads: “The July 12, 2017 ROD calls for a study that could possibly bring back the Bypass. We will remain vigilant throughout this study process to work to stop the Bypass from being resurrected.”

In an effort to learn more about the FRA’s intentions, Town Council President Deborah Carney spoke last August with Amtrak’s chief executive officer, William J. Flynn, who said the most likely route for a New Haven to Providence high-speed rail track would be along the Interstate 95 corridor.

Carney, who said she had been put in contact with Flynn by a mutual acquaintance in Charlestown, acknowledged that while there is no guarantee that plans for the original bypass that would have bisected the town would not be revived, she felt reassured that the I-95 route would be preferred.

“They’re doing the feasibility study and analysis, so there’s no concrete plan at all, but [Flynn] said if they were to go forward with something, it would most likely either to parallel Route 95, like the northern part of the state, or it would involve improving the existing line that goes along the southern coast - where it is now.”

Rhode Island Department of Transportation (DOT) director Peter Alviti represents the state on the 18-member FRA Northeast Corridor Commission (NECC), which is studying rail demand and capacity in the Northeast New Haven to Providence rail corridor.

Alviti, and DOT intermodal programs chief Stephen Devine, met in November with Charlestown officials, Rhode Island state Rep. Blake Filippi, R-New Shoreham, and state Sen. Elaine Morgan, R-Hopkinton.

Alviti told the group the NECC would require a study of future ridership demand on the New Haven to Providence route before any decision was made. (DOT did not support the originally proposed Old Saybrook to Kenyon bypass.)

DOT spokesperson Charles St. Martin said in a recent emailed statement that his agency was counting on more public consultation this time around.

“Yes, RIDOT met recently with Charlestown officials regarding this proposal,” he said. “We told them we are aware that Amtrak is retaining a consultant to do an initial market study only to first determine the demand for higher speed services. This effort will be starting soon and will include a robust public participation component.”

St. Martin also noted, “Rhode Island’s position remains the same as in 2017, when the state indicated opposition of the bypass route in Charlestown.”

What still vexes some Charlestown officials, however, is the continued lack of any FRA response to the town’s inquiries.

In August 2021, at the request of the Town Council, town administrator Mark Stankiewicz wrote a letter to FRA interim administrator Amit Bose, asking for more information regarding the New Haven to Providence study.

After receiving no response to the first letter, Stankiewicz sent a second letter on Dec. 10, which read, in part, “Given the limited available information and the absence of any communication from the FRA, we are in a quandary as to how to ensure Charlestown receives timely information and is able to relay our input and concerns about the New Haven to Providence Capacity Planning Study.”

Charlestown Planning Commission chair Ruth Platner, who was not mollified by Flynn’s statements, said she had not expected the FRA to respond.

“I’m not surprised that they’re not answering, but I think it’s important that the town is asking,” she said. “The thing is, they took the [Old Saybrook to Kenyon] bypass out of the decision, but they didn’t replace it with anything, and the whole rail plan is based on the assumption that there’s going to be huge job growth in the big cities — in Washington, Philadelphia New York and Boston, but that’s not Rhode Island and that’s not Connecticut. The high-speed rail is to connect those big cities, and they want to do it, one way or another.”

Platner said she believed that pandemic-related changes which have made it possible for many Americans to move out of large cities and work from home will impact the study.

“I think what’s happened now, because of the pandemic, there’s kind of a wait and see, to see what this means for growth. Are the cities not going to grow?” she said.

Another factor to consider, Platner said, is the proximity of the I-95 corridor to the coast, and therefore, its vulnerability to rising sea levels.

“It’s a beautiful ride, and it’s right along the coast, and the water is right there. The tracks are going to be under water, so they have to do something, and the problem has to be solved, and it’s going to be solved with some sort of realignment away from the coast,” she said.

Carney said her concerns had been largely put to rest after her conversation with Flynn and the meeting with Alviti.

“In our conversations with Peter Alviti, and also William Flynn, it doesn’t seem as though that Old Saybrook to Kenyon is going to be revived, but I understand where people are coming from,” she said. “You know, if it’s their property that’s impacted, obviously they’re concerned about it, but I will say that Director Alviti kind of put our minds at ease, you know, in saying ‘This is not in the 10-year plan.’”

Platner, however, warned the affected towns to remain vigilant.

“The town of Charlestown needs to be involved, so that we can protect the people and the environment here,” she said. “What we don’t want is to have a plan be created that we don’t know about.”

The FRA did not respond to several requests for comment.

Cynthia Hammond is an ecoRI News contributor

Caitlin Faulds: Trying to save a drowning coastal marsh

Wenley Ferguson, of Save the Bay, and many others have spent more than five years trying to save the drowning Sapowet Marsh, in Tiverton. R.I. marsh.

— Photo by Caitlin Faulds/ecoRI News)

Common reed (Phragmites australis) is an invasive species in degraded marshes in the Northeast.

Salt marsh during low tide, mean low tide, high tide and very high tide (spring tide).

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

TIVERTON, R.I.

The grasses are dying. Clusters of broken, denuded stems stand in shallow pools of brackish water, making a patchwork of the low-lying marshlands.

The slow balding is invisible from the blacktop of Seapowet Avenue, hidden behind a thick curtain of phragmites. But standing boot-deep in the peat, surrounded by the sulfuric scent of decomposition, the bare ground is clear evidence of the steady saltwater creep happening in marshes across Rhode Island.

Spartina alterniflora, or smooth cordgrass, is notoriously salt-tolerant and a common feature in saltwater marsh environments.

“They can grow along the edge of the cove and get flooded twice a day, but they can’t grow in standing water,” said Wenley Ferguson, shovel in hand. All around, the sunlight glints off pools of standing water, unable to drain and slowly growing with each high tide.

The average sea level in Rhode Island has increased by about a foot since 1929. Storm surges and king tides have pushed further and further inland. Normally, the marsh would respond to the rising high-water line by matching the migration inland.

But with the sea on one side and a dense web of roads, development, cultivated fields, and invasive species on the other — and accelerated sea-level rise on its way — Sapowet Marsh has nowhere to move.

But Ferguson, the director of habitat restoration at Save The Bay, is working to save the marsh from that saltwater grave.

Ferguson has been working with the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) at the Sapowet Marsh Wildlife Management Area, a 260-acre state property, for more than five years now.

The coastal edge of Sapowet has seen more than 90 feet of shoreline erosion in the past 75 years. Under Ferguson’s watch, Sapowet has become home to the largest marsh migration facilitation project in the state — a small counter to the forces at play.

“When I say facilitate marsh migration,” she said, “it’s kind of like prepping the land for the marsh to migrate.”

Back in 2017 and 2018, Save The Bay and DEM, along with the Tiverton Conservation Commission, restored 9 acres of coastal grassland and reestablished beachside dunes on the northern side of the marsh to slow erosion.

Now the work has moved to the west and southeast sides of the marsh — and the strategy has changed to match.

Along the western front

The cordgrass roots are taut, but they cut easy. Just one stomp and the shovel sinks through the muck, water pooling up and over the toes of Ferguson’s black rubber boots.

It was a warm and clear November day — too warm, according to Ferguson. She packed for a cool fall day and wore a blue-flowered fleece, but 60 degrees means she’ll be sweating by midday.

Earlier in the week, Ferguson — along with a handful of DEM employees and volunteers — used shovels and a small excavator to dig a weaving network of runnels through the marsh. These shallow creeks will give the pooling water a route out to Narragansett Bay, allowing the area to slowly drain.

If the root zone of the marsh plants is able to dry even slightly, they will grow “healthy and happy,” Ferguson said. Healthy plants build up a stronger root base, and a stronger root base makes a coastline more resilient to erosion and sea-level rise.

But “we don’t want to drain it too fast,” she said. It has been three days since they dug the first runnels and the water level has dropped only slightly, exposing a few inches of bare mud — exactly as planned.

The standing water is thick with unconsolidated sediments and topped by a bacterial mat. If the water rushes out all at once, this sediment will pour into the bay. It’s better to dig in phases and let it settle out in the marsh, maintaining as much high ground as possible.

They are back on this day to adjust the runnels, excavating the areas where the muck has naturally dammed up. Lucianna Faraone Coccia, a Save The Bay volunteer and an environmental science master’s student at the University of Rhode Island, shovels out a cluster of grass roots.

“If that’s in there, it could plug up this whole runnel,” said Faraone Coccia, glancing down to point out a fiddler crab fumbling its way along the channel with its unbalanced claws.

With each shovel-full, the flow of water grows incrementally stronger and piles of dislodged peat beside the runnels grow larger.

“That’s technically considered fill,” said Ferguson, tossing another glob of peat toward the pile beside her. “We actually leave the peat on the marsh and we create these small little islands.”

These islands are about a chunk of peat thick —some 6-12 inches, not too high, Ferguson said — but that small elevation rise “is like a mountain in a marsh.”

Ferguson fought to keep the peat in the marsh, acquiring additional permits from the Coastal Resources Management Council, DEM’s Office of Water Resources, and the Army Corps of Engineers. This microtopography is essential for a healthy marsh surface, she said.

“These areas will just be a little higher, and they might recolonize,” Ferguson said. “And when I say might — they do recolonize.”

Within one season, the islands will host new sprouts of cordgrass, or they’ll prove high and dry enough to support clusters of high marsh grasses. The clusters of high grass will make ideal nesting habitat for the saltmarsh sparrow.

As healthy salt marsh has waned, so has the population of the saltmarsh sparrow — a bird that makes its nest out of a cup of dense high marsh grasses. The nests are built to withstand the highest moon tides, created with a dome so “the eggs float, but they don’t float out of the nest,” Ferguson said. But the area here is flooding too frequently, contributing to nest failure.

“That’s why these little islands that we’re creating are really valuable habitat,” Ferguson said.

Wenley Ferguson is constantly looking for clues to what shaped the marsh seen today.

Old ways and leftover lines

The state of marshes today are the result of centuries of human development and marshland intervention. According to Ferguson, nearly every marsh in the country holds some sort of historical impact. They are in no way pristine.

“So many of them were manipulated in this area for agricultural activity. And then in more recent years, we put roads along them,” Ferguson said. “We culverted them. We created duck habitat and impounded them. We filled them.”

From the 1700s to the 1900s, about 50 percent of marshes in the region were filled, according to Ferguson. Agricultural embankments have manipulated the marsh surface too, dating back to about the 1600s, when people started haying in these areas.

“The fresher the marsh grasses, the fresher the water table, the greater the value of the hay,” she said.

When she digs these runnels, Ferguson is always scouting for clues to what shaped the marsh seen today. A shovel full of root matter means a stagnant pool was once a field. Water pooling along straight lines could be a sign of an old embankment. Long straight trenches are likely remnants of old mosquito ditches — once made to reduce mosquito breeding grounds but now speeding marshland erosion.

The marsh’s tired past — coupled with its location in an old river valley whose steep sides make marsh migration difficult — spell out a challenging future.

“That’s why what we’re doing today is trying to restore some health of the marsh … under current conditions,” Ferguson said, “but always looking at where the marsh wants to go.”

An excavator heads into a thicket of phragmites growing on the eastern edge of Sapowet Marsh.

The eastern blockade

“Be careful of your eyes walking through this,” said John Veale, habitat biologist with DEM’s Division of Fish and Wildlife, as he pushed away the sharp corners of dozens of broken phragmites. “It can be a little bit dangerous.”

In the past century, invasive phragmites species — few native phragmites remain — have taken advantage of weakened saltwater marsh ecosystems to rampage through North American. The eastern edge of Sapowet Marsh, tucked below Old Main Road and several DEM-owned cornfields, is no different.

In many ways, phragmites are the perfect storm. Their feathery seed heads catch the light beautifully, but they also catch the wind and spread like wildfire. Once the seeds take hold, the reeds grow so densely they all but eliminate animal habitat and outcompete native grasses.

On Sapowet Marsh, it serves as an impenetrable blockade to marsh migration. Only a few grapevines are brave enough to reach their tendrils into the thicket. For the marsh to move away from the encroaching seawater, the phragmites need to loosen their hold. But that’s a notoriously difficult task.

“There’s no way we could do it with a shovel,” Ferguson said. “I mean, it’s just so hard. It’s one thing a little patch of phragmites. It’s another thing when it’s head-high.”

Mowing and burning do little to control phragmites, and pulling them out by the roots quickly proves costly. But like the smooth cordgrass, it is vulnerable to salt water. If Ferguson can drain the pooling fresh water and facilitate tidal flow up into the phragmites, they might dissipate — and the native grasses might have a chance at survival.

“We’re not going to get rid of the phragmites, but we can reduce the height and vigor of the phrag by facilitating that freshwater drainage,” she said.

Ferguson is in the early stages of battle on this front, just figuring out the plan. The phragmites grow 10-12 feet high in places, obscuring the lay of the land.

“There’s enough water,” Ferguson said. “It’s coming from someplace. I just can’t figure out the drainage cause it’s too thick.”

She has called in the help of an excavator. Within a few hours, the machine has established a clearing in the reeds and deepened part of a natural creek. Once some of the standing fresh water drains it will be easier to gauge the direction of the water flow.

Ferguson and her team intend to elongate the creek and the old agricultural ditches — putting past mistakes to better use — but for now the plan is still in development. Better to move slowly than be patching more mistakes up in a hundred years.

“The deterioration along the marsh edge is pretty remarkable, in a terrifying sort of way in my mind,” said Ferguson, pausing to point out a flock of buffleheads skimming into the water. “So that’s why we want to be really cautious on not making new openings for that erosion to expand upon.”

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

Caitlin Faulds: Trying to keep climate change from turning more toxic at N.E. waste sites

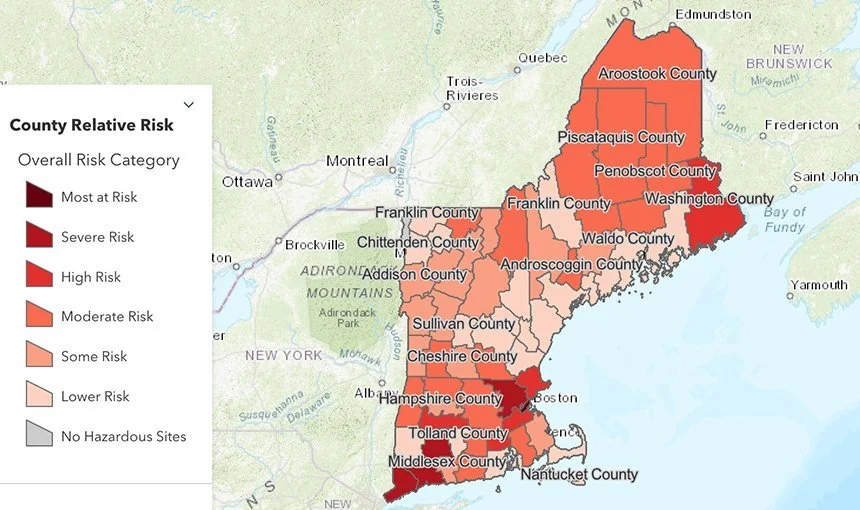

Providence County, in Rhode Island, and Suffolk County, in Massachusetts, are two of the most at-risk counties in New England from pollution buried at toxic sites.

— Conservation Law Foundation map

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Hazardous-waste sites and chemical facilities pockmark New England, leftovers of the region’s industrial past. And little action is being taken to prevent climate change from affecting these sites and cooking up a toxic future, according to analysts at the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF).

A regional report by CLF Massachusetts released this fall combined projections of climate risk with data on social vulnerability and hazardous- waste sites to build a comprehensive map of anticipated toxic-pollution risk from Connecticut to Maine. The results, which show that much of New England could face compounding threats, are startling — even to the mapmakers.

“I bought a house like six months ago … and was actually surprised by the number ... of [Superfund] sites that are in such close proximity to residential neighborhoods,” said Deanna Moran, CLF Massachusetts director of environmental planning. “It’s a little bit scary, but it’s a healthy amount of fear.”

In Rhode Island, Providence County was determined to be the county at highest risk, due to a combination of moderate wildfire risk, severe heat risk, high social vulnerability and 143 hazardous sites. Massachusetts’ s Suffolk County, which includes Boston, was deemed most at-risk in New England.

“A lot of people don’t realize how ubiquitous hazardous sites are, even Superfund sites are, throughout our region,” Moran said. “Even if a site is under remediation or fully remediated, those are the sites that we are still worried about because they were remediated without climate change at the forefront.”

The county-level analysis factors in risk associated with nearly 3,000 hazardous sites. These New England locations include landfills, Superfund sites, brownfields and 1,947 facilities across the region that generate large quantities of hazardous waste or are permitted for the treatment, storage or disposal of toxic chemicals. Many of these hazardous sites are aging, use failing technology, and/or do not have sufficient safeties in place to protect nearby communities in a warmer world, according to the CLF report.

“The techniques that we used to remediate those sites 20 years ago might not anticipate more extreme precipitation or flooding or heat,” Moran said, “and those are the ones that I think are really concerning ’cause they’re really not on the radar.”

Floods could damage infrastructure containing hazardous waste, trigger chemical fires, hinder technology monitoring toxic pollution, and create a toxic stew of floodwater and contaminants, according to the report. Rising temperatures could damage protective caps over contaminated properties and raise the toxicity level of some materials. Wildfires could ravage hazardous-waste sites, damaging protective infrastructure and releasing airborne contaminants.

The lineup of climate risks — which, according to CLF Massachusetts policy analyst Ali Hiple, were “weighted equally” in the report — paints a bleak scene of the region’s future, a future that has been glimpsed in isolated events across the country in recent years.

“Luckily, we have not seen that type of impact in the New England region yet, but we want to make sure that we’re being proactive now and not reactive later,” Moran said.

But despite knowing the dangers that climate poses, federal agencies “are not doing enough to address them, and that puts our communities in danger,” according to the CLF report. In 2019, a U.S. Government Accountability Office report suggested the Environmental Protection Agency should consider climate to ensure long-term Superfund site remediation and protection plans.

“We really just want to see the EPA really leading on this,” said Saranna Soroka, a legal fellow at CLF Massachusetts. “They’ve indicated they know the risk that climate change poses to these sites … but we want to see really consistent, really clear standards applied.”

Soroka noted that the federal agency could analyze climate impact as part of its existing Superfund-site review framework, which mandates site checks every five years. So far, climate analyses have not been incorporated, she said, despite EPA authority to do so.

“I think we’re well beyond the time of thinking through how we should be doing this,” Moran said. “We know the risks are real. In some cases, we’re already seeing them, and the time to be acting on them is now.”

Editor’s note: Here are links to EPA-designated Superfund sites in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

Todd McLeish: Small rodents play important roles in maintaining woodland ecosystems in N.E.

Female White-Footed mouse on sumac bush.

— Photo by Peterwchen

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When University of Rhode Island teaching professor Christian Floyd brought students in his mammalogy class to a nearby forest in September to set 50 box traps to capture mice and other small mammals, he was surprised the next morning when more than half of the traps contained a live white-footed mouse.

“I usually expect to catch three or four, and on a good year we’ll get about 12, but you never get 50 percent trap success,” URI’s rodent expert said. “White-Footed Mouse populations fluctuate in boom and bust years, and this year seems to be a boom year.”

Floyd speculated that abundant acorns, recent mild winters and healthy growth of concealing vegetation were probably factors in the unusual numbers of mice captured this year. But whatever the reason for their abundance, healthy mouse populations are a good sign for local forests.

A new study by scientists at the University of New Hampshire concluded that small mammals such as mice, voles, shrews and chipmunks play a vital role in keeping forests healthy by eating and dispersing the spores of mushrooms, truffles, and other fungi to new areas.

According to Ryan Stephens, the post-doctoral researcher at UNH who led the study, all trees form a mutually beneficial relationship with fungi. Healthy forests are dependent on hundreds of thousands of miles of fungal threads called hyphae that gather water and nutrients and supply it to the trees’ roots. In return, the trees provide the fungi with sugars they produce in their leaves. Without this symbiotic relationship, called mycorrhizae, forests would cease to exist as we know them.

Different fungal species enhance plant growth and fitness during different seasons and under different environmental conditions, so maintaining diverse fungal communities is vital for forest composition and drought resistance, according to Stephens.

But fungal diversity declines when trees die because of insect infestations, fires and timber harvests. That is why the role of small mammals in dispersing mushroom spores is so critical to forest ecology.

To effectively support healthy forests, Stephens said these animals must scatter spores of the right kind of fungi in sufficient quantities and to appropriate locations where tree seedlings are growing. But not every kind of small mammal disperses all kinds of spores, so it’s imperative that forest managers support a diversity of mammal species in forest ecosystems.

“By using management strategies that retain downed woody material and existing patches of vegetation, which are important habitat for small mammals, forest managers can help maintain small mammals as important dispersers of mycorrhizal fungi following timber harvesting” and other disturbances, Stephens said. “Ultimately, such practices may help maintain healthy regenerating forests.”

Distributing mushroom spores isn’t the only important role played by mice and voles in the forest environment. They are also tree planters.

“Almost all rodents cache food — they have a cache of acorns, seeds, maybe truffles, little bits of mushrooms,” Floyd said. “Our oak forests are probably all planted by rodents. They scurry around and dig holes and bury things.”

White-Footed Mice, which Floyd said are the most abundant mammal in Rhode Island, are also voracious consumers of the pupae of gypsy moths.

“For a mouse, gypsy moth pupae are like little jelly donuts; they’re a delicacy,” he said. “The theory is that when mouse numbers are high, they can regulate gypsy moth populations.”

Mice, voles, shrews and chipmunks are also the primary prey of most of the carnivores in the forest, from hawks and owls to foxes, weasels, fishers, and coyotes. These small mammals are a vital link in the food chain between the plant matter they eat and the larger animals that eat them.

Are these small mammals the most important players in maintaining healthy forests? Probably not. Floyd believes that accolade probably goes to the numerous invertebrates in the soil. But this new research on the dispersal of mushroom spores by mice and voles may move them up a notch in importance.

Todd McLeish is an ecoRI News contributor.

Todd McLeish: Weasels seem to be declining in New England and elsewhere in U.S.

The Long-Tailed Weasel seems to be the most common weasel in New England.

A Long-Tailed Weasel in winter coat

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A national study of weasels from across much of the United States has revealed significant declines in all three species evaluated, which has a local biologist wondering about the status of the animals in Rhode Island.

The study by scientists in Georgia, North Carolina and New Mexico found an 87-94 percent decline in the number of least weasels, long-tailed weasels, and short-tailed weasels harvested annually by trappers over the past 60 years.

While a drop in the popularity of trapping and the low value of weasel pelts is partially to blame for the declining harvest, the researchers still detected a significant drop in the populations of all three species.

“Unless you maybe have chickens and you’re worried about a weasel eating your chickens, you probably don’t think about these species very often,” said Clemson University wildlife ecologist David Jachowski, who led the study. “Even the state agency biologists who are charged with tracking these animals really don’t have a good grasp on what is going on.”

The three weasel species are small nocturnal carnivores that feed primarily on mice, voles, shrews, and small birds, often by piercing their preys’ skull with their canine teeth. The weasels prefer dense brush and open woodland habitats, where they search for prey among stone walls, wood piles, and thickets. Because of their secretive nature and cryptic coloring, they are difficult to find and observe.

By assessing trapper data, museum collections, state statistics, a nationwide camera trapping effort, and observations reported on the internet portal iNaturalist, the scientists found the animals to be increasingly rare across most of their range.

“We have this alarming pattern across all these data sets of weasels being seen less and less,” Jachowski said. “They are most in decline at the southern edges of their ranges, especially the Southeast. Some areas like New York and the Canadian provinces can still have some dense pop ulations in localized areas.”

Jachowski noted weasel populations in southern New England are likely facing similar declines as the rest of the country. He believes, however, there is the potential for some areas of the Northeast to still have robust numbers of weasels, especially long-tailed weasels, which are considered the most common of the three species.

Charles Brown, a wildlife biologist at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, who contributed data to the national study, said in his 20 years of monitoring mammal populations in the Ocean State, the only one of the three weasel species he has found is the long-tailed weasel.

“I’ve had a few infrequent encounters with them over the years and seen a few dead ones on the road,” he said. “A mammal survey done in the 1950s and early ’60s documented two short-tailed weasels, and those are the only records I’ve found for the species.”

Least weasels are not found within 300 miles of Rhode Island.

Brown has contributed 19 or 20 long-tailed weasel specimens to the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University over the years from many mainland communities, including Little Compton, East Providence, Warwick, and South Kingstown. Weasels are not known to inhabit any of the Narragansett Bay islands.

“It’s hard to say what their status is here,” he said. “Trappers might bring in one or two a year, and some years none, and we don’t have any other indexes to monitor them because they’re cryptic and we rarely see them.”

Brown said a monitoring program could be developed for weasels in the state using track surveys and camera traps, but because the animals have little economic value and do not cause significant damage, they have not been a priority to study.

“In a perfect world, I’d certainly like to try to find a specimen of a short-tailed weasel to see if they’re still around here, but I have nothing to go on about them from a historic perspective,” he said.

Data from the University of Rhode Island is helping to provide a current perspective of the species’ distribution. URI scientists recently concluded a five-year study of bobcats and the first year of a study of fishers, each using 100 trail cameras scattered throughout the state. Among the 850,000 images collected so far are about 150 photos of long-tailed weasels.

According to Amy Mayer, who is coordinating the studies, the weasel images were collected at numerous locations around the state, suggesting the population does not appear to be concentrated in any particular area of Rhode Island.

It is uncertain what could be causing the national decline in weasel numbers, though Jachowski and Brown believe the increasing use of rodenticides, which kill many weasel prey species, could be one factor. A recent study of fishers collected from remote areas of New Hampshire found the presence of rodenticides in the tissues of many of the animals.

“How it’s getting into the food chain in these remote areas, we don’t know,” Brown said. “There was some discussion that a lot of people go up there to summer camps, and when they close the camp up for the season, they bomb it with rodenticides to keep the mice out. That’s just speculation, but it makes sense.”

The decline of weasels may also have to do with changes to available habitat, the scientists said. The maturing of forests and decline of agricultural land has caused a reduction in the early successional habitats the animals prefer. Brown also believes the recovery of hawk and owl populations, which compete with weasels for mice and voles and which may occasionally kill a weasel, could also be a factor.

Jachowski said the findings from his national study have led to the formation of what he is calling a “weasel working group” to share data and discuss how to monitor the animals around the country. Brown is among the state biologists and academic researchers who are members of the group.

“We’re hoping the public will become involved, too, by reporting their sightings to iNaturalist,” Jachowski said. “We need to see where they persist, and then we can tease out what habitats they’re still in, what regions, and then do our studies to figure out what kind of management may be needed.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.e

Todd McLeish: Some photographers are dangerously disturbing birds

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The increasing popularity of bird photography and the desire of photographers to showcase their images on social media is raising concerns that birds are being harassed and disturbed, leading to potentially harmful effects on their health.

Bird-conservation organizations around the globe, from the National Audubon Society to Britain’s Royal Society for the Preservation of Birds, are asking bird photographers to avoid getting too close and reminding the photographers of the codes of ethics that many wildlife photography organizations have established.

Local wildlife advocates have noted that it’s also an increasing problem in Rhode Island.

“It’s definitely a problem here, and it’s getting worse,” said one longtime birder who wished to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals. “There are more photographers, and there are more forums that photographers can post their photos on. It’s an ego trip for them. They want to post their photos and get likes, and that leads them to harass the birds.”

Laura Carberry, refuge manager at the Audubon Society of Rhode Island’s Fisherville Brook Wildlife Refuge, and Rachel Farrell, a member of the Rhode Island Avian Records Committee, said getting too close to wild birds can pose serious dangers to them. Birds see people as predators, and when people approach, the birds must stop feeding and instead exert extra energy they may not have to escape the area. They also may be forced to leave their nests unattended, making their eggs and chicks vulnerable to predation, thermal stress, or trampling.

When a rare European bird was discovered at Snake Den State Park, in Johnston, R.I., last year and birders and photographers flocked to the site to observe the visitor, some photographers chased the bird across a farmer’s fields to get better photographs. Birders say that is a common occurrence whenever rarities are discovered.

Owls are particularly sensitive to disturbance, Farrell said, and the managers of Swan Point Cemetery, in Providence, have resorted to putting yellow caution tape from tree to tree around an area where great horned owls have nested in recent years to keep photographers from going too close.

“I remember seeing a photographer banging a stick against the bottom of a tree to get an owl to come out of its hole,” Farrell said.

Other birders recalled when a photographer played a recording of a screech owl for so long that one of the nestlings almost fell out of the nest because it was so distressed by the recording.

According to Carberry, Audubon has occasionally had to close parts of its refuges when owl nests have been discovered because photographers go off trail and disturb habitats to approach the nest. The organization has asked birders not to report where owls are nesting until after the breeding season to reduce the problem.

“We often tell people that if the bird is looking at you, you’re too close,” she said.

It’s not just a problem with photographers, however. Some birdwatchers are also at fault for similar behaviors. Some will play audio recordings of bird songs to attract the birds out into the open, for example, a practice condemned by ornithologist Charles Clarkson, the director of avian research at the Audubon Society of Rhode Island.

“The daily energetic demands of birds are extremely high, even when they are not actively nesting,” he said. “Distracting birds from essential tasks — foraging, preening, defending territory — can leave them in an energy deficit, which is difficult to make up,” he said. “To lure birds in using taped calls can have serious negative consequences for individual birds and even local bird populations where taped calls are used regularly. It’s best to leave birds be and use your own power of observation to find as many as possible.”

How to resolve the problem is unclear. Enforcing codes of ethics is difficult, and speaking up sometimes results in abusive responses. The Atlantic Flyway Shorebird Initiative is surveying birders and bird photographers to assess the scale of the problem and to see if educational messaging and communication tools could be developed to address the issue.

“I think folks lose sight of what they may be doing to the species they are trying to get a glimpse of or take a photo of,” Carberry said. “They should always think of the bird first and think if they are impacting it in any way. I think that if they put the birds’ needs first, they would be more careful about approaching a nest or getting a little too close.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Todd McLeish: Artificial light threatens animal populations

Light pollution is mostly unpolarized, and its addition to moonlight results in a decreased polarization signal.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Global insect populations have declined by as much as 75 percent during the past 50 years, according to scientists, potentially leading to catastrophic impacts on wildlife, the environment and human health. Most studies point to habitat loss, climate change, industrial farming and pesticide use as the main factors driving the loss of insects, but a new study in the United Kingdom points to another cause: light pollution.

The ever-increasing glow of artificial light from street lights, especially LED lights, was found to have detrimental effects on the behavior of moths, resulting in a reduction in caterpillar numbers by half. And since birds and other wildlife rely on caterpillars as an important food source, the consequences of this decline could be devastating.

According to Douglas Boyes of the British Center for Ecology & Hydrology, street lights cause nocturnal moths to postpone laying their eggs while also making the insects more visible to predators such as bats. In addition, caterpillars that hatch near artificial light exhibit abnormal feeding behavior.

But moths are not the only wildlife affected by artificial light.

Since most songbirds migrate at night, birds that have evolved to use the moon and stars as navigational tools during migration often become disoriented when flying over a landscape illuminated with artificial light.

“City centers that are very bright at night can act as attractants to migrating birds,” said ornithologist Charles Clarkson, director of avian research at the Audubon Society of Rhode Island. “They get pulled toward cities, and when they find themselves amid heavily lit buildings, they become disoriented, leading to a large number of window strikes and increased mortality.”

It is unclear why birds are attracted to lights, but studies have found increasing densities of migrating birds the closer one gets to cities.

“Birds probably see these cities on the horizon from a long distance, and they get pulled toward these locations en masse,” Clarkson said.

Street lights have also been found to be problematic to birds. Birds are active later into the evening when they are exposed to nearby artificial lighting at night, and they often sing later as well.

“Sometimes that might lead to more food availability, since lights attract insects,” Clarkson said. “But it also affects the physiology of the birds when they’re active when they should be sleeping. Some birds that live in heavily lit urban or suburban areas begin nesting earlier, too, up to a month earlier than they typically would. And that leads to a phenological mismatch between when food is traditionally available and when the chicks are hatching and need to be fed.”

Artificial lighting may cause other species to face a similar mismatch. Christopher Thawley, a lecturer and researcher in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Rhode Island, studied lizards in Florida and found not only that the reptiles advanced the onset of breeding when exposed to artificial light, but they also laid more eggs and even grew larger under artificial lighting conditions. Other kinds of wildlife could have comparable results.