Philip K. Howard: A radical centrist platform for 2020 --replace red tape with individual responsibility

Centrist politics don’t offer the passion of absolutist solutions. In the words of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.): “Moderate is not a stance. It’s just an attitude towards life of, like, ‘meh.’”

But electoral success in 2020 likely will hinge on who attracts the centrist voters. One issue seems to unite most Americans: Frustration with how government works. Political scientist Paul Light recently found 63 percent of voters support “very major reform” of federal government, up from 37 percent 20 years ago.

For several decades, Americans have elected “outsider” candidates who promise some version of Barack Obama’s “change we can believe in.” Yet nothing much changes. The elections of Obama and Donald Trump can be viewed as symptoms of unrequited reform. When Obama’s promise of change got bogged down, 8 million Obama voters turned around and voted for Trump. Now Trump’s promise to “drain the swamp” is headed towards futility, amounting to little more than reversing Obama-era executive orders.

What’s missing is a governing vision that makes Americans part of the solution. Only then can leaders attract the popular mandate needed to overcome the resistance of Washington. Only then will there be a principled basis for officials and citizens to make practical choices going forward.

The best model for modern government is to revive the framework of democratic responsibility designed by the Framers: Replace red tape with human responsibility at all levels of society. This governing vision, though centrist, requires a radical simplification of Washington bureaucracies.

Over the past 50 years, almost without anyone noticing as it happened, the jungle of red tape in Washington has grown progressively denser — at this point 150 million words of detailed statutes and regulations (over 180,000 pages of the Code of Federal Regulations and over 40,000 pages of the U.S. Code). The effects of this build-up include bureaucratic paralysis and pervasive micromanagement of daily choices throughout society.

Bureaucracy is staggeringly costly. Common Good’s 2015 report, “Two Years, Not Ten Years,” found that a six-year delay in permitting infrastructure more than doubles the effective cost of projects. Twenty states now have more non-instructional personnel than teachers in their schools, mainly to comply with legal reporting requirements. The administrative costs of American health care are estimated to be as much as 30 percent — that’s about $1 trillion, or $1 million per physician.

Bureaucracy is a prime source of voter alienation. Many Americans today don’t feel free to be themselves — almost any decision, comment, joke, or child’s play activity can involve legal risk. Rule books tell us how to correctly run schools and provide social services. Small businesses are put in an almost impossible position of being regulated by multiple agencies with detailed requirements — a family-owned apple orchard in New York state, for example, is regulated by about 5,000 rules from 17 different regulatory programs. Fear of offending employees leads many companies to impose speech codes that, studies suggest, exacerbate discriminatory feelings.

Since Ronald Reagan’s tenure in the White House, the Republican mantra has been deregulation. Yet what frustrates most Americans is not public goals, such as safeguarding against unsafe work conditions, but micromanaging exactly how to organize a safe workplace with thousands of detailed rules. One-size-fits-all regulations often drive Americans to resistance, because rigid rules don’t honor tradeoffs, local circumstances, or a sense of proportion in enforcement.

This reform vision is simple: Focus regulation on goals and guidelines. Simpler codes will allow Americans to understand what is expected of them and will afford them flexibility to get there in their own ways. The reform is also radical: Legacy bureaucracies must be largely replaced with these simpler codes. Detailed rules would be limited to areas such as effluent limits where specificity is essential. The resulting regulatory overhaul would be historic, comparable in magnitude to the Progressive Era.

Area by area, recodification commissions would propose to Congress new codes. Public goals that require practical choices, such as overseeing safe and adequate services, would allow flexibility and local innovation. Instead of Big Brother breathing down our necks, Washington would be more like a distant uncle, intervening only when citizens or local officials transcended boundaries of reasonableness.

Not that long ago, that’s how government was organized. The Interstate Highway Act in 1956 was 29 pages long. Ten years later, over 20,000 miles of highway had been built. By contrast, the most recent highway bill was almost 500 pages long, and implemented by thousands of pages of regulations.

Law is more effective when people focus on goals. The Constitution is only 15 pages long, but its principles nonetheless are effective to protect our freedoms. Agencies where officials take responsibility for ultimate goals, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention with its focus on disease reduction, accomplish more than those such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which is organized around rote compliance with thousands of rules.

No one designed the current bureaucratic tangle. It just grew and grew more, as each ambiguity sprouted a new rule. Leaders can’t lead it, because the rules trump common sense. But that’s precisely why a new movement is needed. Legacy bureaucracies never fix themselves.

Philip K. Howard is chair of Common Good and author of the new book Try Common Sense (W.W. Norton, 2019). Follow him on Twitter@PhilipKHoward.

TAGS ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ DONALD TRUMP BARACK OBAMA POLITICS OF THE UNITED STATES DEMOCRATIC PARTY REPUBLICAN PARTY 2020 CAMPAIGN FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

Let managers manage; watch the rowers from a fixed-up ‘Red Bridge’

The Henderson Bridge (aka “Red Bridge”) over the Seekonk River.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Some good and bad news in Rhode Island the past few days.

Let’s start with the bad news. The well-regarded and reformist Providence schools superintendent, Christopher Maher, has decided to step down. And while he gave a frequently used explanation for exits – to spend more time with his family – another reason seems to be that he’s frustrated by the bureaucratic limits on his ability to get things done to improve the city’s schools – improvement they urgently need.

The fact is that the superintendent needs far more freedom to improve the system. World War II Adm. Chester Nimitz famously said: “When you’re in command, command,’’ but the Providence schools chief is remarkably hamstrung. As Hillary Salmons, executive director of the Providence After School Alliance, told The Providence Journal in the Feb. 27 article “Another schools chief is leaving”:

“When the City Council controls any {expenditures} over $5,000 how can anyone manage his resources? It’s going to be hard to attract leadership with a district hamstrung by these structural impediments.’’

People in authority should be given, well, authority to do what needs to be done and of course be held accountable for their decisions. I keep citing my friend Philip K. Howard’s books on red tape and bureaucratic paralysis, the latest entitled Try Common Sense. It seems very appropriate here.

There need to be changes to enable future Providence school superintendents to actually manage their department.

xxx

On a happier note is news that the nearly crumbling Henderson Bridge (aka “Red Bridge”), connecting the East Side of Providence with East Providence, will be rebuilt in a fashion to make it more of a public asset.

The new version will be narrower, with only two lanes instead of the current unnecessary four lanes (put in for a superhighway that never happened), but will include bike/pedestrian paths in both directions. Thus the bridge will offer people in our area yet another way to enjoy the views up and down the Seekonk River as it enters Narragansett Bay, and get exercise while doing it. It will be a fine place from which to watch the Brown crew and other rowers on the river,

Kudos to the Rhode Island Department of Transportation for this plan.

By the way, my favorite writer about bridges and other transportation infrastructure is Henry Petroski – e.g., see his book The Road Taken: The History and Future of America’s Infrastructure.

Philip K. Howard: Red tape has replaced responsibility

For decades now, Americans have slogged through a rising tide of idiocies. Getting a permit to do something useful, say, open a restaurant or fix a bridge, can take years. Small businesses get nicked for noncompliance of rules they didn’t know. Teachers are told not to put an arm around a crying child. Doctors and nurses spend up to half the day filling out forms that no one reads. Employers no longer give job references. And, in the land of the First Amendment, political incorrectness can get you fired.

We’d all be better off without these daily frustrations. So why can’t we use our common sense and start fixing things?

But common sense is illegal in Washington. Red tape has replaced responsibility. No official has authority even to do what’s obvious. In 2009, Congress allocated $800 billion, in part to rebuild America’s infrastructure. But it didn’t happen because, as President Obama put it, there’s “no such thing as a shovel-ready project.” Even President Trump, a builder, can’t get infrastructure going. The entire government was shut down in a spat over one project, the Mexican border wall, that the parties don’t agree on. How about fixing the broke rail tunnel coming into New York?

Washington’s ineptitude is only the tip of the iceberg. A bureaucratic mindset has infected American culture. Instead of feeling free to do what we think is right, Americans go through the day looking over our shoulders: “Can I prove that what I’m about to do is legally correct?”

Every Republican administration since Reagan has promised to cut red tape with deregulation. “Washington is not the solution,” as Reagan put it: “It’s the problem.” But Washington has only gotten bigger during their terms in office. That’s because deregulation is too blunt: Americans want Medicare, clean water, and toys without lead paint.

Americans are not stupid. Government drives people nuts because it prevents anyone from being practical. Nothing’s wrong with requiring a permit for a new restaurant, but should you have to go to 11 different agencies? Who has the job of moving things along in Washington and making sure officials focus on real issues? That would be, uh, no one.

No one designed Washington’s giant bureaucracy either. It just grew, like kudzu, since the 1960s. Its organizing idea is to tell everyone exactly how to do everything correctly. Mindless compliance replaced human judgment. A new problem? Write another rule. The steady accretion of rules is why government has become progressively paralytic over the past few decades.

Back in the old days, of say, JFK or the late Sen. Majority Leader Howard Baker, government fixed problems by giving some official that job and then holding them accountable. Congress authorized the Interstate Highway System with a 29-page statute, and nine years later over 21,000 miles had been built. Today, the red tape would probably prevent it from being built at all.

It’s time to bite the bullet: Washington can’t be repaired; it must be replaced. Creating a coherent governing framework is not so daunting. Most bureaucratic detail is irrelevant when people are allowed to take responsibility again.

Instead of bickering over a laundry list of reforms, Americans should demand a few core principles:

* Radically simplify regulation. Law should set goals, not require mindless compliance with thousand-page rulebooks. Let Americans take responsibility and meet public goals in their own ways. More local control will not only work better but restore pride and self-respect.

* Accountability is key. Democracy is toothless without accountability. Accountability today is lost in legal quicksand and then strangled by public unions. Fairness should be protected with oversight, not exhausting lawsuits.

* Shake up Washington. Obsolete laws, bureaucratic stupor, partisan politics and lobbyists’ money all preserve the status quo. Reboot everything. Disrupt the electoral process by changing campaign rules. Move most agencies out of Washington — the bureaucratic culture there is toxic. Let the FDA go to Boston or San Diego. Send the worker safety agency to Ohio.

Experts say that change is impossible, pointing to the gridlock in Washington. Incremental change may be impossible, but big change is inevitable. Americans are fed up. That’s why they elected Donald Trump president and why Democrats are steering to the far left.

What’s missing is not public demand for change but a coherent vision of how Washington can work again. My proposal is basic: Replace the dense bureaucracy and put humans in charge again. Empower Americans, at all levels of responsibility, to make practical and moral daily choices. Then hold them accountable for how they do. Let Americans be American again.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, civic leader and writer, is chairman of Common Good and author of Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left.

Move the FDA to Boston?

]

Harvard Medical School quadrangle in Longwood Medical Area, Boston.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com:

One of the most intriguing of the ideas in \Philip K. Howard’s new book – Try Common Sense: Replacing Failed Ideologies of the Left and Right -- is to move a lot of federal operations out of Washington to get them away from the entrenched lobbyist-run corruption there and closer to the people and in some cases to outstanding local expertise. Such moves would liberate more federal employees to take decisions in the public interest.

The crux of Mr. Howard’s books is that people should exercise more individual judgment and take on more responsibility instead of turning over so much of their lives to regulations and legalism. They should be encouraged to exercise common sense.

“All the ligaments and tendons of Washington’s permanent apparatus – civil servants, lobbyists, lawyers, contractors, media and politicians – are conditioned to play their roles in its giant bureaucratic apparatus.’’ (I happen to think that the civil servants are the best of the lot….)

So Mr. Howard writes: “How can we govern sensibly or morally when officials in Washington refuse to change direction? The answer is that we can’t. …Why fight this culture head on? Start moving agencies out of Washington to places where people are not afraid of taking responsibility.’’ Big companies move all the time. Why not agencies? And some could be moved to places with considerably lower operating costs than metro Washington.

Mr. Howard suggests, for example, that the Food and Drug Administration’s headquarters could be moved to Boston or California, where there are many, many physicians, biologists and others in health-care-related fields. Or the Department of Housing and Urban Development could go to Detroit. Consider that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention works well with its Atlanta headquarters.

This redistribution would also more fairly share the vast wealth associated with the federal government, which is so heavily concentrated in the Washington, D.C., region, which vies with San Francisco as the richest metro area in America.

Whether or not you agree with Mr. Howard on this or that policy proposal, you have to give him credit for, as he told me, “trying to change how people think about’’ government and civil society/citizenship in general. That has to be the start.

Oh yes, let’s move all or part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to the great ocean research center of Woods Hole.

A view of downtown Woods Hole from the water, including Marine Biological Laboratory and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

'Try Common Sense'

— Graphic by Olga Generozova

Commentary has begun on Philip K. Howard’s new book, Try Common Sense, available Jan. 29.

TIME highlights it as a "Book to Read": "As the rhetoric between American political parties grows more tense, Philip K. Howard offers a solution based in practicality."

Reason.com says the book "offers up concrete proposals not just to reform government but to route around it and get on with our lives." Listen to the recent Reason Podcast interview with Philip here.

Leading thinkers such as Jonathan Haidt, Former Sen. Alan Simpson, Mary Ann Glendon and George Gilder have strongly endorsed the book.

On the other hand...a review by Mark Green in this Sunday's New York Times attacks the book, asking: "Is now really the best time for a jeremiad against 'regulation'?" Because the book attacks left-wing ideologies (as well as those on the right), it's perhaps not surprising that Green, a prominent left-wing partisan, doesn't deal with the actual themes of the book - including how to make regulation practical.

More to come soon...

On Jan. 30, Philip will be discussing Try Common Sense at Politics and Prose in Washington, D.C. The event is free and open to the public.

On Feb. 19, Common Good and The Center on Capitalism and Society at Columbia University will host a morning forum, Bureaucracy vs. Democracy, discussing the need to reboot legacy bureaucracies. Details will follow, but you can RSVP now by emailing rmgiverin@commongood.org.

Philip K. Howard: How to make a deal to address America's infrastructure crisis

A photo by Philip K. Howard in his "Peripheral Visions'' series, much of it about transportation infrastructure, some of it crumbling. To see more, please hit this link.

President Trump this week reiterated his commitment to “rebuild our crumbling infrastructure.” He called upon Congress to enact a law that “generates at least $1.5 trillion” and also to “streamline the permitting and approval process — getting it down to no more than two years, and perhaps even one.”

This would be an enormous boon to society, improving not only America’s competitiveness, but also creating a greener environmental footprint — while adding more than a million new jobs.

But environmental groups are lining up in opposition even before they’ve seen the details. Streamlining red tape, they argue, requires gutting environmental regulations. Are they really in favor of bloated processes that can take a decade or longer and produce impenetrable 5,000-page environmental review statements?

The facts are not on their side. A 2015 report by my organization, Common Good, found the following:

Other greener countries such as Germany approve large projects in less than two years, including environmental review.

A typical six-year delay in large projects more than doubles the effective cost of the projects.

Lengthy environmental reviews often harm the environment by prolonging polluting bottlenecks.

Modernizing America’s infrastructure is a necessity, not an ideology. Rickety transmission lines lose 6 percent of their electricity, the equivalent of 200 coal-burning power plants. About 2,000 “high-hazard” dams are in deficient condition. Century-old water-mains leak over 2 trillion gallons of fresh water a year. Over 3 billion gallons of gasoline are consumed by vehicles idling in traffic jams. Half of fatal car accidents are caused in part by poor road conditions.

Fixing this doesn’t require changing, much less gutting, environmental protections. Common Good has presented Congress with a three-page legislative proposal that creates clear lines of authority to make decisions on a timely basis: An environmental official would be authorized to focus the review on material issues, not thousands of pages of trivial detail; the White House could resolve disagreements among bickering agencies; federal law would preempt delays by state and local governments on interstate projects; and lawsuits would be expedited and limited to material environmental harms, not foot faults.

No one intended environmental review or permitting to take a decade. Current regulations say that analyses in complex projects should not exceed 300 pages. But the review for raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge, a project with virtually no environmental impact (it used the existing bridge foundations), was 20,000 pages including exhibits. This is bureaucratic insanity.

What the current process does is give environmental groups a veto. Just by threatening to sue, they can drag processes on for years. But where in the Constitution does it empower naysayers to call the shots? Environmental review should not be used to prevent elected officials from making decisions.

Funding is also obviously needed. The political deal is obvious: Democrats should agree to streamline permitting as long as Republicans provide adequate funding. Most roads and other such projects lack a revenue stream and require public funds. It’s a good investment, returning about $1.50 for every dollar spent, according to Moody’s. It’ll be an even better investment when effective costs are cut in half by streamlining permitting.

Trump’s initiative is a moral as well as a practical imperative. We are living off the infrastructure built by our grandparents and their grandparents. What shape will it be in when we bequeath it to our grandchildren?

New York has choke points that can’t tolerate any further delay. The two rail tunnels coming into Penn Station from New Jersey are over 100 years old, and were badly damaged by Superstorm Sandy. When they shut down for repairs the result is “carmageddon” — 25-mile gridlock.

The approach bridge to those tunnels is made of iron and wood, and occasionally catches fire or gets stuck when pivoting open for barge traffic — causing trains to wait for hours. The “Gateway project” for two new tunnels is essential to avoiding economic and environmental chaos, and almost ready for construction. It needs permits and money. Congress has to provide it.

On fixing America’s transportation woes, it’s time to link arms, not use any pretext to oppose this plan.

Philip K. Howard is chairman of the nonpartisan Common Good (commongood.org) reform organization and a New York-based civic leader, lawyer, author (including the best-selling The Death of Common Sense), and photographer. He's also an old friend, classmate and sometime colleague of New England Diary editor Robert Whitcomb. This piece first ran in The New York Post.

News as you move

Where we still read newspapers.

Photo by Philip K. Howard (www.philipkingphoto.com)

Mr. Howard is a New York-based lawyer, civic leader, author (including of the best-seller The Death of Common Sense) and photographer.

Philip K. Howard: 4 approaches to fixing America's infrastructure

An image from Philip K. Howard's "Peripheral Visions'' photos, which he has taken over the years, especially in cities. This goes along with his public-policy expertise in America's infrastructure, especially regarding transportation.

He says: "These images frame the repetitive patterns of daily landscapes that we feel but rarely consciously observe. Shot on 35mm film at slow shutter speeds to convey how most of us experience these moments, they are impressionistic, with large prints taking on a pointillistic quality.'' Mr. Howard's photos can been seen at philipkingphoto.com.

A new White House office of innovation, led by Jared Kushner, has been created to apply business techniques to make government work better. Leaving aside state enforcement powers, much of what government does is deliver (or subsidize) goods and services. What would have to change to make those government functions more business-like?

Fixing America’s fraying infrastructure, for example, enjoys broad public support. As a builder, President Trump would seem uniquely qualified to oversee this initiative. But government can’t seem to get projects moving. Only 3.6 percent of the $800 billion 2009 stimulus plan was put to use on transportation infrastructure. No one was able to make the needed choices—as President Obama put it, “there’s no such thing as shovel-ready projects.”

How would a business go about fixing America’s infrastructure? It would make choices in four broad categories, none of which Washington will do.

1. Set priorities. Washington has no action plan to rebuild the rickety power grid, or to prioritize interstate bottlenecks. It basically leaves the setting of projects to states and localities—as with the “bridge to nowhere.”

Solution: Put someone in charge of setting national priority projects, which then receive federal support. Australia, for example, has a central committee that receives applications from states and decides which get federal support.

2. Cut red tape. Decade-long review and permitting procedures compromise or kill projects by a) doubling the effective cost, b) creating uncertainty that discourages public and private capital from sponsoring projects, and c) skewing project design toward mollifying whoever threatens to sue. Lengthy environmental review—often thousands of pages of mind-numbing detail—turns out to be harmful to the environment in most cases, because it delays fixing polluting bottlenecks.

Solution: Set deadlines (two years maximum for major projects; six months for fix-it projects), and create clear lines of authority to make needed decisions. Only Congress can do this. Scores of well-meaning laws since the 1960s have resulted in a jumble of competing obligations and balkanized authorities, at the federal, state and local levels.

Clear lines of authority are essential; that’s how greener countries such as Germany are able to approve major projects within a 1-2 year timetable. The nonprofit Common Good, which I chair, has a three-page legislative proposal that: a) gives the chair of the Council of Environmental Quality, who reports to the president, the job of keeping environmental reviews focused on important issues; b) gives the director of the OMB the authority to resolve all interagency disputes and to balance competing regulatory concerns; c) preempts state and local approvals for national projects if their approval processes extend beyond federal timetable, and; d) expedites and limits lawsuits.

3. Outsource design and construction. Most businesses, like government, have no special know-how in large construction projects. Typically, businesses solicit “design-build-maintain” bids which put the contractor on the hook for long-term success of the infrastructure. Government, by contrast, tries to “spec” out every detail in advance—with the predictable result that government fails to anticipate contingencies and ends up paying for costly change-orders and higher maintenance.

Solution: Require best-practices procurement as a condition for federal infrastructure aid. Other countries, such as Australia, make much more use of so-called 3P arrangements (Public-Private partnerships), even in situations where the infrastructure has no revenue stream and the developer is repaid out of general tax revenues. It is generally more cost-effective to let private developers take the risks of the numerous contingencies and to bear the responsibility of maintenance.

4. Don’t be reluctant to invest in good projects. Businesses look at the return on capital invested. By most accounts, the economic benefits of fixing America’s infrastructure are huge—returning $5.20 on each $1 invested in modernizing the Interstate highway system, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers. Plus 2 million jobs. Plus a greener footprint.

A business would use whatever financing was available to achieve returns on this level. It would even raise price of products if it thought it customers saw the benefit. If a penny-pinching business let its physical plant deteriorate, to the harm of its customers, it would soon be taken over by someone else. Perhaps that’s what happened in the last election.

Solution: This should be the easiest change, because it requires no legal amendments. The Republicans’ refusal to consider any new revenue streams to fix broken infrastructure is another symptom of its dysfunction. Ask Alexander Hamilton: Raising revenues to invest for the greater good does not violate conservative principles. The decision here could hardly be more obvious: For example, a 25-cent rise in the gas tax, which has stayed at the same level for a quarter century, would finance about half of President Trump’s ten year trillion-dollar initiative.

Washington will resist these changes, because, unlike business, it doesn’t want to make new choices. That requires someone taking responsibility. In Washington, the deck is stacked for the status quo—no new infrastructure without a decade of review, no permit without approval from a dozen agencies, no new taxes even if traffic bottlenecks cost billions. No is everywhere. Maybe no is a good presumption for new laws, but not when government needs to deliver goods and services.

Back in the old days, when Washington leaders worked things out, the deal for an infrastructure initiative would be obvious. Democrats agree to streamline environmental review, and Republicans agree to raise taxes in exchange for a streamlined process that cuts costs in half.

Infrastructure is a kind of canary in the mine of democracy. Everyone says they want infrastructure, but there’s no movement. That’s because dense bureaucracy, by stifling any capacity to deliver projects in a reasonable time frame, has removed the oxygen of democracy. A congressional leader might be more amenable to funding infrastructure if he knows that his district’s stretch of Interstate 80 will get a new lane next year. What Washington needs is what every successful business has: a hierarchy of responsibility that allows responsible people to hammer out accommodations and start making decisions again.

Philip K. Howard is a New York City-based civic leader, author (The Death of Common Sense and The Rule of Nobody among them), lawyer and photographer. He is chairman of Common Good (common good.org), the legal- and regulatory-reform organization.

Philip K. Howard: Blame Congress for our crumbling infrastructure

The infamous Bayonne Bridge.

President Trump has signaled that one of his next big initiatives will be to jump-start a trillion-dollar program to rebuild America's fraying infrastructure. As a former builder, Trump would seem to be uniquely qualified to oversee this initiative.

Rebuilding infrastructure enjoys broad public support, unlike, say, the failed rewrite of Obamacare, The economic benefits will be huge — not only improving America's competitiveness, but returning upwards of $5 on each $1 invested, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers. Two million new jobs would be created.

But it's all talk. What's missing is pretty basic: No one has the authority to say Go. Although supposedly in charge of the executive branch, Trump finds himself in a kind of mosh pit of overlapping statutory responsibilities and inconsistent legal mandates.

Approval processes can take a decade or longer. Environmental reviews, meant to highlight important choices, obscure them in thousands of pages of mind-numbing detail.

For projects that survive this gantlet, the delay dramatically increases costs. Uncertainties over time and cost keep many projects on the sidelines.

Governing shouldn't be this hard. Traffic bottlenecks, overflowing wastewater, rickety power grids, and crumbling dams desperately need to be fixed. All that's needed are responsible officials to give permits and allocate funding.

Who's to blame here?

Shine the spotlight on Congress. For 50 years, under Democratic and Republican control alike, Congress has piled up law after law, many with absolute mandates to protect endangered species, preserve historic structures, guarantee access to the disabled and scores of other well-meaning goals.

The accretion of statutes is matched 10:1, more or less, by agency regulations written to implement Congress's mandates. All these laws give enforcement power to 18 or so separate federal agencies — sometimes all on the same project. To top it off, almost anyone can sue based on alleged failure to comply with any of the countless requirements.

It's amazing anything gets built.

The red-tape idiocies are illustrated by the project to raise the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge, which spans the Kill Van Kull connecting New York Harbor with the Port of Newark. The roadway is too low for the larger "post-Panamax ships" (designed for the newly-widened Panama Canal), and the Port Authority thought it needed to spend $4 billion to build a new bridge or tunnel.

Then a long-time Port Authority employee, Joann Papageorgis, figured out that the roadway could just be raised within the existing arch of the bridge. The solution was like a miracle: It not only reduced costs from $4 billion to $1 billion, but also had virtually no environmental impact since it used the same foundations and right of way as the existing bridge.

Raising the Bayonne Bridge roadway was pro-environmental in every meaningful way. It would permit cleaner, more efficient ships into Newark Harbor, and avoid the environmental havoc to surrounding neighborhoods of a new bridge or tunnel.

But no official had authority to approve it without hacking through a jungle of red tape.

Here's some of the red tape: a requirement to study historic buildings within a two-mile radius even though the project touched no buildings; notice to Native-American tribes around the country to participate even though the project would not be disturbing any new ground; and 47 permits from 19 different agencies.

It doesn’t get more complicated than this

The environmental review for this project — again, a project with virtually no environmental impact — was 20,000 pages, including appendices. Proceeding on an expedited timetable, permits were finally awarded after five years. Then some self-styled environmentalists sued claiming….you guessed it, "inadequate review." The Port Authority started construction anyway, and hopes to complete the project in 2019, 10 years after the application was filed.

Where is Congress?

Only Congress has the power to change old laws, to make sure they work in the public interest. Congress's responsibility also includes making sure laws work together. Viewed alone, a law may seem perfectly reasonable.

But if all the laws cumulatively harm the public, then Congress has the obligation to change them.

The problem is, in the vast majority of cases, Congress doesn't even have the idea of fixing old law. It treats old law like the Ten Commandments — except that now it's more like the Ten Million Commandments.

Like sediment in a harbor, the accretion of old law prevents America from getting where it needs to go. What's missing is not mainly money: President Obama had over $800 billion in the 2009 stimulus but, five years later, had been able to spend only 3.6 percent on transportation infrastructure. As he put it, "there's no such thing as shovel-ready projects."

What's missing is that no human has authority to use their common sense.

The harm to the public is intolerable. A study by Common Good, which I chair, found that the red-tape delays for infrastructure more than double the cost of large projects. The study also found that lengthy environmental review is dramatically harmful to the environment by prolonging polluting bottlenecks.

Environmental review is a good idea, but something is obviously amiss when the review of the environmental effects actually is environmentally harmful.

Greener countries like Germany are able to do environmental reviews and permitting on major projects in one to two years. The secret to their success is — hold on to your hats — to let officials take responsibility to make needed decisions.

All the red tape in America comes from a deliberate congressional philosophy to prevent humans from making decisions. Everything is preset in laws and rules. Thus, in American government, the concept of relevance is irrelevant.

That's why the Bayonne Bridge required a study of historic buildings even though no buildings were affected. That's why the new Tappan Zee Bridge project was required to do traffic studies even though the new bridge was not affecting traffic flow.

Restoring responsibility to officials to make decisions is the only way to end this red tape paralysis. It doesn't mean they can do whatever they want — they would still have to do an environmental review, accountable to the President and to courts in egregious cases.

But instead of overturning every pebble, officials could focus on what's important. "Oh, you're just raising the bridge roadway using the same foundations? Give 50 pages on construction impacts of the project" (not 20,000 pages).

Restoring clear lines of authority is actually simple. Common Good has proposed three pages of legislative fixes to make this vision a reality. The proposal empowers officials to determine the scope and adequacy of review, to intercede in inter-agency disputes and to expedite lawsuits to keep projects moving.

Trump recently signed an executive order designed to expedite approvals a little by giving coordinating authority to a designated official. That recommendation was based in part on Common Good's work. Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao declared recently: "Business as usual is just not an option anymore." Even Senate Democrats'' proposed infrastructure plan commits to "accelerated project delivery." But talking about fixing the problem isn't enough.

Trump ultimately doesn't have legal authority to ignore these statutory dictates. Congress created all this bureaucracy. Only Congress can fix it.

And how about funding the infrastructure initiative, whenever it materializes? Congress has its head in the sand here as well.

Trump has vowed to push for a decade-long, $1 trillion initiative. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, the infrastructure backlog is actually over $4 trillion, including: congestion on 40 percent of Interstate Highways; an antiquated power grid that wastes the equivalent of 200 coal-burning power plants; in New York State, 2,000 structurally deficient bridges and, in New York City leaky water mains that are almost a century old.

Delays on some of these projects could be disastrous. The two rail tunnels under the Hudson River, for example, are over 100 years old, and were damaged by superstorm Sandy. When they are forced to shut down for emergency repairs, the traffic jams could stretch for 25 miles.

Two new tunnels and other rail upgrades in and out of Penn Station are almost ready for construction. But this "Gateway Project" costs over $20 billion. Even with expedited reviews, and funding from state and local government, it will take a major financial contribution from Washington.

Yet Congress, or more accurately, the Republicans in Congress, refuse to advance any responsible plan to fund an infrastructure initiative. They don't dispute that infrastructure funding would be an excellent public investment — improving competitiveness, adding jobs and building a greener footprint. The sticking point is the Republican mantra — almost a theology — that they can never, never ever, raise any taxes.

Infrastructure does not, however, grow on trees. Trump in his campaign suggested that infrastructure could be funded with private investment.

Indeed, some infrastructure projects, such as transmission lines and toll roads, can be financed privately because they have revenue streams. But adding new lanes on congested highways, shoring up old dams and expanding sewage capacity will generally require public funding.

Where can infrastructure funding come from? One obvious source is the gasoline tax, which hasn't increased in 24 years. Raising the gasoline tax by 25 cents would raise over $40 billion per year, and fund most needed highway and transit projects. This could be supplemented by a "carbon tax" on other fossil fuels. Another funding source would be tax revenue from repatriated offshore corporate earnings.

New fees and taxes come out of our pockets, of course. But kicking the can down the road will cost us far more. An hour stuck in a traffic jam is multiple times more expensive than an extra 25 cents on each gallon of gasoline. Deferring maintenance is generally economically disastrous — increasing costs by a factor of 10, as occurred when the cables and girders of Williamsburg Bridge had to be replaced due to decades of neglect.

Doesn't Congress have a responsibility to do what's right here? Our parents and great-grandparents paid for the infrastructure that we now use. A great city, a great country, can't thrive with decrepit roads, rails and pipes.

Every time you're in a traffic jam — starting, say, this afternoon — think about Congress. It created a paralytic regulatory structure that prevents fixing infrastructure. Now it also refuses to help pay for it. Only Congress can cut these bureaucratic knots, raise funds, and get America moving again.

Philip K. Howard is chairman of Common Good, a legal- and regulatory-reform organization, a New York City-based civic leader, a lawyer, author of, most recently. The Rule of Nobody and a photographer.

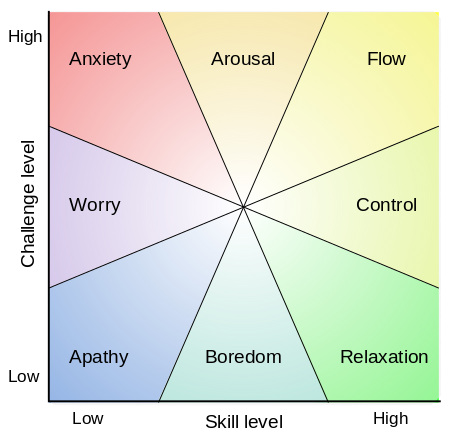

Philip K. Howard: Repairing Democracy in an age of distrust

Democracy can’t earn the allegiance of its citizens with centralized dictates. We need to have our say, and be free to do things in our own way. This crisis of democratic identity can’t be resolved merely with new policies at the top. Top-down government is itself the problem. Americans now have an historic opportunity to reimagine government. The key is to abandon the centralized operating philosophy which, in thousand-page rulebooks, purports to tell everybody how to do everything. Government must still protect against abuse—otherwise freedom will be destroyed by bad actors just as surely as it is by suffocating bureaucracy.

Americans now have an historic opportunity to reimagine government. The key is to abandon the centralized operating philosophy which, in thousand-page rulebooks, purports to tell everybody how to do everything. We need to re-empower human agency at all levels of society.

The Trump revolution was not a Republican revolution. It was a revolt against Washington. Voters wanted someone who would shake things up. The new President’s mandate is for change, but what kind of change? The campaign did not exactly illuminate a new vision for how to govern.

Since the election, Republican leaders have pulled off the shelf their standard agenda, including broad de-regulation. But I doubt if disaffected voters are dreaming about fixing Dodd-Frank or corporate taxes. Voters seemed to be lashing out in every direction. Many are upset at stagnant wages and a perception that jobs are disappearing.

But voters were angry at more than that. They seemed tired of being talked down to by political phonies and know-it-all bureaucrats. They were tired of political correctness and mindless bureaucracy in their schools, hospitals, and workplace. Anger comes from the gut, not the mind. No clear policy agenda emerged from the Trump campaign because the struggle was not about policy. It was about a sense of frustration, alienation, and powerlessness. There can be a kind of wisdom in crowds.

Democracy can’t earn the allegiance of its citizens with centralized dictates. We need to have our say, and be free to do things in our own way. This crisis of democratic identity can’t be resolved merely with new policies at the top. Top-down government is itself the problem. Americans now have an historic opportunity to reimagine government. The key is to abandon the centralized operating philosophy which, in thousand-page rulebooks, purports to tell everybody how to do everything. Government must still protect against abuse—otherwise freedom will be destroyed by bad actors just as surely as it is by suffocating bureaucracy.

But government can protect freedom by adopting an oversight role that guards against abuses rather than micromanaging daily choices. Communities ought to be able to run schools and provide services in their own way, within broad boundaries. Regulatory dross of all sorts—HIPAA privacy forms, and most warnings and disclaimers—should be revised or scrapped, because they insult our common sense and cumulatively interfere with our ability to focus on what’s important. There are some areas where centralized, detailed regulation is needed—say, pollution discharge limits. But in areas that hinge on human attitudes and competence—say, workplace safety or school discipline—too many rules and protocols are generally counterproductive. Far better for government to stand at a distance, making sure people don’t breach the boundaries of reasonableness.

Guarding outer boundaries is the traditional mechanism of law—acting as a kind of dike against misconduct. Law is vital to freedom because it affirmatively protects an open field of free interaction. Law sets “frontiers, not artificially drawn, within which men should be inviolable,” as Isaiah Berlin put it. Law today doesn’t protect an open field of freedom; it more often strangles daily choices with dictates that make no sense in the circumstances.

Scrapping the micro-regulation model is not a matter of degree—not merely cutting back on red tape. American government requires an historic shift of operating philosophy, one that puts humans back in the driver’s seat. Law must be the framework, but human responsibility must be the activating mechanism. The goal is to liberate people to try to do what’s right and sensible, accountable to those around them.

So far, so good. But there’s a bone here that will stick in throat of ideologues from both sides. Without a thick rulebook, the official must be free to use his or her best judgment. How else can he use common sense, when applying legal principles to the particular circumstances, to decide when conduct is unfair or unsafe? Oversight for results almost always requires human judgment. The paradox of freedom, forgotten in recent decades, is that empowering citizens requires empowering officials to fulfill their legal responsibilities.

This is not just the Hobbesian requirement of police protection. The interdependence of the modern world puts a huge burden on government oversight. People you don’t know are taking care of your loved ones in schools and nursing homes. How can you influence them if the official in charge is not empowered to act sensibly? The parents’ ideas don’t matter if the principal doesn’t have authority to act on them. The current void of human authority disempowers everyone. People don’t feel they, or anyone around them, can roll up their sleeves and fix things. The answer to every frustration is the same: “The rule made me do it.” (President Obama, explaining why the 2009 stimulus couldn’t be used to fix broken infrastructure: “There’s no such thing as shovel-ready projects.”)

The solution to powerlessness—the only solution—is to re-empower human agency at all levels of society. I’ll assert two first principles that hold the key to remaking a healthy democracy: Principle One: Human choice at implementation is required for accomplishment. Nothing good in the history of mankind was created except when a human, or group of humans, made it happen. Rules, and law in general, can prevent bad things from happening, and can establish protocols for joint action. But even those negative goals cannot be accomplished with a selfexecuting legal structure. Following rules mindlessly crowds out what Michael Polanyi called “tacit knowledge,” the vast store of instincts and know-how that resides in our subconscious.

Most people don’t know and cannot clearly articulate how they get things done. Trial and error—the opposite of compliance—is the secret sauce of progress. No endeavor can succeed, management expert Peter Drucker found, without “a principle of management that will give full scope to individual strength and responsibility.”

Principle Two: Personal ownership of choices is required for self-fulfillment. People want to make a difference. It gives us a sense of self-worth. Doing things in our own way requires freedom to adapt, adjust, and try new things. Being stymied by a rulebook, or trudging all day through compliance checklists, makes people miserable. Anomie, now hardened into anger, comes mainly from a feeling of personal unimportance. People with rote jobs have higher levels of stress and heart disease, while, paradoxically, people with more responsibility and personal risk feel less tension and are healthier.

Tocqueville here as in other areas put his finger on the misery of self-executing systems: “It is especially dangerous to enslave men in the minor details of life. For my own part, I should be inclined to think freedom less necessary in great things than in little ones” because, otherwise, “their spirit is gradually broken…” Humans need to be in charge. Only then can things get done sensibly. Only then does democratic accountability mean anything.

Today, the FAA certifies new aircraft as “airworthy” based on their expert judgment, not detailed specifications like how many rivets it has. This is not “de-regulation,” but an all too-rare liberation of American common sense inside government. When humans are allowed to take responsibility, law becomes far simpler and more effective. A few legal principles can replace a thousand rules if people are free to take responsibility for implementation. To regulate nursing homes, Australia replaced a thick rulebook with 31 results-oriented principles, such as to have a “home-like setting.” Within a short period nursing homes had improved markedly. Why? Professors John and Valerie Braithwaite found that all stakeholders—nurses, regulators, and families—now focused on making homes better instead of mindless compliance with a thousand input-oriented rules.

Letting humans focus on results would transform every area of public concern. For example, within a year we could get America rebuilding its decrepit infrastructure—just by giving an environmental official the job of deciding when there’s been sufficient environmental review. Today, multi-year environmental reviews obscure, not illuminate, vital issues, and often cause environmental harm by prolonging bottlenecks. Schools and government agencies would have a lot more zip if principals and managers could make basic personnel decisions without having to endure a years-long legal trials to prove that someone doesn’t do the job. Everybody knows who the bad teachers are; site-based oversight committees could guard against vindictive or unwise decisions. Recently Bill Bradley, Mitch Daniels, Tom Kean, and Al Simpson joined with the nonprofit Common Good, which I chair, to launch a campaign (“Who’s in Charge Around Here?”) advocating the radical simplification of government so that people can take charge again.

Human responsibility was, of course, the founding concept of our Republic: Elect and appoint people who have the job of using their best judgment for the common good. James Madison could hardly have been clearer: “It is one of the most prominent features of the Constitution, a principle that pervades the whole system, that there should be the highest possible degree of responsibility in all Executive officers thereof; anything, therefor, which tends to lessen this responsibility is contrary to its spirit and intention.”

Principles-based regulation would actually make law comprehensible to real people—a core tenet of the rule of law ignored by the mandarins in Washington. Again, Madison: “It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that the cannot be understood.” Democracy will be revitalized when officials can take responsibility for results. Focusing regulation on goals will also allow people in different communities to do things in different ways. They can take ownership of their choices. As legal philosopher Jeremy Waldron has argued, a principles-based structure offers humans the dignity of being able to argue about right and wrong with a real decision-maker. People won’t feel so powerless any more.

The Wages of Distrust

Distrust is the mortar that keeps the current America governing philosophy firmly in place. Distrust of democracy went into high gear in the 1960s, when we woke up to abuses of racism, pollution, lies about Vietnam, neglect of the disabled, and more. Making law as detailed as possible was the solution chosen to balance against supposedly bad values. There would be no room for abuses of authority if official decisions were prescribed in thick rulebooks. Even some libertarians joined in. They believe in the power of human freedom, of course, but legal control of officials is how they strive to preserve freedom.

Nobel economist Friedrich Hayek, usually a font of wisdom, pronounced in early writings that “government in all its actions . . . [should be] bound by rules announced and fixed beforehand.” It is now received wisdom, among liberal professors as well as industry lobbyists, that laws and regulations should be as detailed as possible. The Volcker Rule is 950 pages of casuistry because lobbyists wrote it that way. Obsessive legal control is a formula not for better freedom, but for mutual powerlessness: The tighter the shackles on the regulator, the tighter the shackles on the regulated. If the nursing home inspector is shackled to a thousand detailed rules, so are the nurses in the nursing home —even if the rules do little or nothing for the quality of the home. Freedom turns out to be a concentric concept. If the traffic cops aren’t free to do their job, then pretty soon you’ll be stuck in gridlock. The citizen’s vote matters only when the President is free to make genuine choices.

John Locke, no fan of centralized authority, concluded that “many things…must necessarily be left to the discretion of him that has executive power in his hands.” The fear that keeps everyone quivering in the legal jungle is also based on a misconception: There’s no need to trust any particular flesh-and-blood official. What’s required is to trust the framework of our republic—to rely on human checks and balances, in which each official is surrounded by other officials who check his fidelity to legal principles.

An official or judge is not, as Justice Benjamin Cardozo put it, “a knight errant roaming at will.” Just as free citizens are not free to breach contracts or cheat others, officials are constrained by their legal mandate. As Ronald Dworkin has put it: “Discretion, like the hole in a doughnut, does not exist except as an area left open by a surrounding belt of restriction…. An official’s discretion means not that he is free to decide without recourse to standards of sense and fairness.”1 Havel viewed democratic authority as a temporary delegation that “is lost when a person betrays that responsibility.”

Our paranoia about official authority is ironic. The rule of law famously fosters trust because it gives people confidence that, say, contracts will be honored and abuse not tolerated. What we’ve forgotten is that law itself is tethered to norms of good faith and reasonableness, applied by judges and officials taking responsibility to do justice in the particular case. Hayek himself recanted his views on the “supposed greater certainty [when]…all rules of law have been laid down in written and codified form.”

Law can only support freedom when a judge or official applies it in a way most people consider reasonable. “Law floats in a sea of ethics,” as Chief Justice Earl Warren put it. Without giving it much thought, Americans generally trust the judges and others who enforce broad principles of civil and criminal law. Government, too, must be tethered to norms of reasonableness. Putting official authority into solitary confinement, hemmed in by impregnable and obsessively detailed law, was supposed to enhance our freedom.

Instead, we locked ourselves in as well. The “simultaneous recession of both freedom and authority in the modern world” is no accident, Hannah Arendt observed. Without a coherent theory of authority, we are “confronted anew…by the elementary problem of human living-together.”

Rebuilding Trust Through Responsible Choices

Here we are in 2016, with half the country in revolt, needing to find a way to live together. We shouldn’t worry too much about abandoning the de facto technocratic regulatory system as it has evolved. Our government “has outgrown the structure, the policies and the rules designed for it,” Peter Drucker observed, with the result that it is “bankrupt, morally as well as financially.” It was an heroic effort but, like central planning, it was doomed to fail because it was built on “the arrogant belief, “as Vaclav Havel put it, “that the world is merely a puzzle to be solved, … a body of information to be fed into a computer in the hope that sooner or later it will spit out a universal solution.”

America requires a new operating philosophy that embraces the unavoidable humanness of governing. Getting past the pervasive distrust is the challenge. Years of public failure and powerlessness feed the distrust. If there were any trusting souls left in America, the 2016 campaign showed that it’s “us versus them.”

The stakes are high. Trusting cultures tend to prosper, as Francis Fukuyama and others have demonstrated, because people can stride toward their goals without fear of ambush. Shared values of fair dealing and common purpose are reinforced by shared norms of reciprocity; you do your part, others will do theirs. People feel they own their own choices, and feel comfortable with trial and error. Success feeds on itself.

Distrust, by contrast, corrodes the foundations for success. Like acid, it weakens our willingness to move forward because we don’t trust other people to do their part. People become defensive, and tiptoe through the day. Transactions slow to a crawl, or don’t happen at all. In Edward Banfield’s study of a backward village in Italy, pervasive distrust removed the conditions for cooperation. Neighbors could not get together to fix roads and other common resources. The local Mayor refused outside subsidies because, he said, his constituents would assume he would pocket much of it.

For the past half century, America has looked to law not only to change values, a good thing, but also to dictate daily choices. Now Washington overflows with law, but it is also a cesspool of distrust. As in Banfield’s village, America’s leaders can’t get together to fix broken roads. People in Washington also huddle within defensive bubbles, treating outsiders as enemies. Political leaders from different parties no longer break bread, much less forge deals to move forward. The White House has walled itself off from the Executive Branch it supposedly runs.

Do Americans really differ on basic values of hard work and fair play? I don’t think so. I think government drove us apart, with the best of intentions, by clogging up society with a giant bureaucratic hairball and by removing our ability to try to work things out for ourselves. People don’t want to be trapped in red tape, and they’re obviously sick of political leaders who act like “puppets…in a giant rather inhuman theatre,” as Havel put it.

Rebuilding trust starts at the top: Leaders must make choices that are trustworthy. President Trump will not be reluctant to start making decisions. But his decisions must be viewed as fair and sensible, with due respect for differing interests. Trust is also a two-way street. If Trump empowers others to do things in their own way, they will be more likely to reciprocate. If his decisions are viewed as high-handed, however, we’ll soon fall back into the maw of too much law. This is an historic and perilous moment. Change is overdue. But it’s not the change advocated by either party. The change needed, to liberate American citizens and to fix American government, is to return to our founding philosophy: to honor humans by creating a framework that empowers them to take initiative, act on their beliefs, and make a difference.

Philip K. Howard is chair of Common Good, a nonprofit government- and legal-reform group, and author, most recently, ofThe Rule of Nobody (2014). This piece first ran in The American Interest.

Philip K. Howard: Start rebuilding America's crumbling infrastructure now

This from our friend Philip K. Howard, who runs Common Good, a reform group:

American voters have rejected the ways of Washington. The challenge is to channel that populist force for positive change.

Here are two initiatives that could enjoy broad support:

1. Start rebuilding infrastructure now. Trump is committed to this, as are Democratic leaders, but he will be stymied unless Congress passes a simple bill creating clear lines of authority to make needed decisions. Otherwise projects will languish in bureaucracy for years as experts write foot-thick reports. (See Common Good’s report “Two Years, Not Ten Years”). The upside here is YUGE: Cut costs in half, build a greener footprint, and create 1.5 million new jobs.

2. Begin simplifying government. Red tape is choking America, including government itself. Trump should announce a new approach to regulating: Simplify law into goals and principles, so that it is understandable and people have room to use their common sense. He should also appoint an outside commission to recommend radically simplified structures. Governing sensibly is impossible in today’s red tape jungle.

If you agree, pass this note along. We have a vision to reconnect Washington to the rest of America.

Copyright © 2016 Take-Charge.org, All rights reserved.

A campaign brought to you by commongood.org.

Robert Whitcomb: Forever and a day to build something

Excerpted from Aug. 18 Digital Diary column in GoLocalProv.

Please, city, don’t hold this up too! MSI Holdings LLC wants a few waivers to build an 11-story retail/residential building on what is now a parking lot on Canal Street in downtown Providence, most notably a waiver that would let the owners exceed the official height limit for the neighborhood in the city’s zoning rules.

The Providence Business News also reports that “the applicant has requested waivers from the recess requirement, and ground floor and upper level transparency requirements for the portion of the building that faces a narrow alley, called Throop Street.’’ Few people would see that side.

The applicant ought to get the waivers promptly. Having lots of parking lots downtown in place of buildings is deadly. They shout urban decay. Density, on the other hand, speaks of vitality and prosperity. Jam in those buildings!

Time and time again, excessively rigid zoning rules have prevented what would be perfectly respectable structures from going up in Providence, or has grossly delayed them. The parking lot that this building would cover is an eyesore. Let’s get as much bustle as we canfrom people and businesses in downtown Providence, an eminently walkable place.

Which gets me to how long it takes to get anything done in Rhode Island.

The Rhode Island Department of Transportation expects to finally award a bid in October to build the long-delayed (for 10 years!) pedestrian bridge over the Providence River, with completion expected by November 2018. It looks like this thing will cost about $20 million.

The bridge will link College Hill and Fox Point with downtown, creating various commercial and other synergies. It should become a kind of tourist site and popular meeting place. Let’s hope that a brilliant architect designs it. Friedrich St. Florian?

Of course, because of the necessary oversight of publicly funded projects, the zoning-ordinance labyrinth, constituency politics and the vagaries of the economy, public projects usually take much longer than private ones. Still, 10 years is far too long! Businesses and individuals take negative notice of places where minor but needed repairs, such as filling potholes, let alone big projects, seem to take eons to happen. Such delays are particularly frustrating in a place as small as Rhode Island, where you might think it would be easier to get things done.

It’s a problem around America.

Common Good, run by my friend Philip K. Howard, has a very useful and proscriptive report out called Two Years, Not Ten Years: Redesigning Infrastructure Approvals that among otherthings discusses the huge costs of delaying infrastructure permits. To read the report, please hit this link.

Robert Whitcomb is the overseer of New England Diary.

Trying to put us back in charge

My old friend Philip K. Howard sent this along. It’s well worth reading, and joining Common Good. http://www.commongood.org/

-- Robert Whitcomb

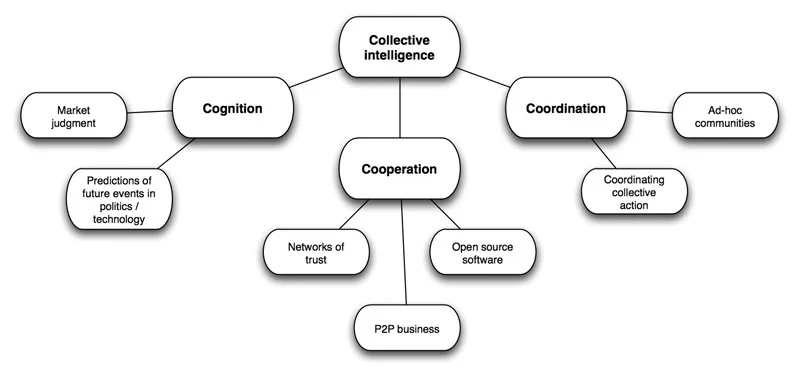

Common Good has launched a national bipartisan campaign – called “Who’s in Charge Around Here?” – to build support for basic overhaul of the federal government.

The campaign, which has been endorsed by leaders from both political parties, will show how to remake government into simple frameworks that let people to take charge again. Rules should lay out goals and general principles – like the 15-page Constitution – and not suffocate responsibility with thousand-page instruction manuals.

The campaign is co-chaired by former U.S. Sen. Bill Bradley (D.-N.J.) and Common Good Chair Philip K. Howard. Among those who have already endorsed the campaign are former Governors Mitch Daniels (R.-Ind.) and Tom Kean (R-N.J.), and former U.S. Sen. Alan Simpson (R.-Wyo.) who co-chaired the Simpson-Bowles Commission on government reform.

Americans are frustrated. They can’t take responsibility. Bureaucracy is everywhere. The president can’t fix decrepit roads and bridges. A teacher can’t deal with a student disrupting everyone else’s learning. Physicians and nurses take care of paperwork instead of patients. A manager can’t give an honest job reference. Parents get in trouble for letting their children explore the neighborhood. Washington does almost everything badly. Take any frustration, and ask: Who’s in charge around here? That’s a problem.

Modern government is a giant hairball of regulations, forms and procedures that prevent anyone from taking charge and acting sensibly. No one designed this legal tangle. It just grew, and grew, and grew, until common sense became illegal. That’s the main reason that government is paralyzed. That’s why it takes a team of lawyers to get a simple permit. Every year, the red tape gets denser.

Our campaign will use video and social media to drive a national conversation to return to Americans the freedom to let ingenuity and innovation thrive in their daily lives. The campaign’s first three-minute video, narrated by Stockard Channing, uses white-board animations to explain how government should work. Titled “Put Humans in Charge,” the video is available here.

Americans know that common sense has taken a backseat to stupidity, but political debate has not drawn a clear link to suffocating legal structures. The campaign features “The Stupid List” showing how obsolete and over-prescriptive bureaucracy undermines infrastructure and the environment, schools, health care, jobs and the economy. The Stupid List is available here.

“Whether you are Democrat or Republican, you are a citizen first,” said Co-Chair Bill Bradley. “A functioning government serves a citizen’s interests. We need sensible reform that encompasses compassion and responsibility. Common Good demonstrates such an outcome is not impossible.”

“Voter frustration with broken government will only grow until Washington reboots to reset priorities and cut needless bureaucracy,” said Co-Chair Philip K. Howard. “It’s time to mobilize for a dramatic overhaul – replacing mindless compliance with common sense. That’s the only way to liberate American initiative and make government responsive to modern needs. America’s global competitiveness depends upon it.”

The campaign’s Website is Take-Charge.org. The campaign is active on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. For further information, contact Emma McKinstry at emckinstry@highimpactpartnering.com.

Common Good (www.commongood.org) is a nonpartisan reform coalition whose members believe that individual responsibility, not rote bureaucracy, must be the organizing principle of government.

The founder and chairman of Common Good is Philip K. Howard, a lawyer and author of The Rule of Nobody (W. W. Norton) and The Death of Common Sense (Random House), among other books.

Philip K. Howard: Congress needs to clean out the stables of long-outdated laws

Government is broken. So what do we do about it? Angry voters are placing their hopes in outsider presidential candidates who promise to “make America great again” or lead a “political revolution.”

But new blood in the White House, by itself, is unlikely to fix things. Every president since Jimmy Carter has promised to rein in bureaucratic excess and bring government under control, to no effect: The federal government just steamed ahead. Red tape got thicker, the special-interest spigot stayed open, and new laws got piled onto old ones.

What’s broken is American law—a man-made mountain of outdated statutes and regulations. Bad laws trap daily decisions in legal concrete and are largely responsible for the U.S. government’s clunky ineptitude.

The villain here is Congress—a lazy institution that postures instead of performing its constitutional job to make sure that our laws actually work. All laws have unintended negative consequences, but Congress accepts old programs as if they were immortal. The buildup of federal law since World War II has been massive—about 15-fold. The failure of Congress to adapt old laws to new realities predictably causes public programs to fail in significant ways.

The excessive cost of American healthcare, for example, is baked into legal mandates that encourage unnecessary care and divert 30 percent of a healthcare dollar to administration. The 1965 law creating Medicare and Medicaid, which mandates fee-for-service reimbursement, has 140,000 reimbursement categories today and requires massive staffing to manage payment for each medical intervention, including giving an aspirin.

In education, compliance requirements keep piling up, diverting school resources to filling out forms and away from teaching students. Almost half the states now have more administrators and support personnel than teachers. One congressional mandate from 1975, to provide special-education services, has mutated into a bureaucratic monster that sops up more than 25 percent of the total K-12 budget, with little left over for early education or gifted programs.

Why is it so difficult for the U.S. to rebuild its decrepit infrastructure? Because getting permits for a project of any size requires hacking through a jungle of a dozen or more agencies with conflicting legal requirements. Environmental review should take a year, not a decade.

Most laws with budgetary impact eventually become obsolete, but Congress hardly ever reconsiders them. New Deal Farm subsidies had outlived their usefulness by 1940 but are still in place, costing taxpayers about $15 billion a year. For any construction project with federal funding, the 1931 Davis-Bacon law sets wages, as matter of law, for every category of worker.

Bringing U.S. law up-to-date would transform our society. Shedding unnecessary subsidies and ineffective regulations would enhance America’s competitiveness. Eliminating unnecessary paperwork and compliance activity would unleash individual initiative for making our schools, hospitals and businesses work better. Getting infrastructure projects going would add more than a million new jobs.

But Congress accepts these old laws as a state of nature. Once Democrats pass a new social program, they take offense at any suggestion to look back, conflating its virtuous purpose with the way it actually works. Republicans don’t talk much about fixing old laws either, except for symbolic votes to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Mainly they just try to block new laws and regulations. Statutory overhauls occur so rarely as to be front-page news.

No one alive is making critical choices about managing the public sector. American democracy is largely directed by dead people—past members of Congress and former regulators who wrote all the laws and rules that dictate choices today, whether or not they still make sense.

Why is Congress so incapable of fixing old laws? Blame the Founding Fathers. To deter legislative overreach, the Constitution makes it hard to enact new laws, but it doesn’t provide a convenient way to fix existing ones. The same onerous process for passing a new law is required to amend or repeal old laws, with one additional hurdle: Existing programs are defended by armies of special interests.

Today it is too much of a political struggle, with too little likelihood of success, for members of Congress to revisit any major policy choice of the past. That’s why Congress can’t get rid of New Deal agricultural subsidies, 75 years after the crisis ended.

This isn’t the first time in history that law has gotten out of hand. Legal complexity tends to breed greater complexity, with paralytic effects. That is what happened with ancient Roman law, with European civil codes of the 18th Century, with inconsistent contract laws in American states in the first half of the 20th Century, and now with U.S. regulatory law.

The problem has always been solved, even in ancient times, by appointing a small group to propose simplified codes. Especially with our dysfunctional Congress, special commissions have the enormous political advantage of proposing complete new codes—with shared pain and common benefits—while providing legislators the plausible deniability of not themselves getting rid of some special-interest freebie.

History shows that these recodifications can have a transformative effect on society. That is what happened under the simplifying reforms of the Justinian code in Byzantium and the Napoleonic code after the French Revolution. In the U.S., the establishment of the Uniform Commercial Code in the 1950s was an important pillar of the postwar economic boom.

But Congress also needs new structures and new incentives to fix old law.

The best prod would be an amendment to the Constitution imposing a sunset—say, every 10 to 15 years—on all laws and regulations that have a budgetary impact. To prevent Congress from simply extending the law by blanket reauthorization, the amendment should also prohibit reauthorization until there has been a public review and recommendation by an independent commission of citizens.

Programs that are widely considered politically untouchable, such as Medicare and Social Security, are often the ones most in need of modernization—to adjust the age of eligibility for Social Security to account for longer life expectancy, for example, or to migrate public healthcare away from inefficient fee-for service reimbursement. The political sensitivity of these programs is why a mandatory sunset is essential; it would prevent Congress from continuing to kick the can down the road.

The internal rules of Congress must also be overhauled. Streamlined deliberation should be encouraged by making committee structures more coherent, and rules should be changed to let committees become mini-legislatures, with fewer procedural roadblocks, so that legislators can focus on keeping existing programs up-to-date.

Fixing broken government is already a central theme of this presidential campaign. It is what voters want and what our nation needs. A president who ran on a platform of clearing out obsolete law would have a mandate hard for Congress to ignore.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, civic leader and writer, is the founder of the advocacy group Common Good and the author, most recently, of The Rule of Nobody.