Logan in the '50s: Close parking and pew space

Seems to have been adequate parking close to the terminals at Logan International Airport in the late ‘50s! Note the chapel at the right. Perhaps such airport chapels were bigger then because the more dangerous aviation of the time pulled in more people to pray before takeoff, and to buy flight insurance.

Let behemoths bargain with behemoths

Behemoth and Leviathan, watercolor by William Blake from his Illustrations of the Book of Job.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

So consolidation of New England’s health-care biz continues apace. Two big Massachusetts-based health insurers – Harvard Pilgrim Health Care and Tufts Health Plan -- plan to merge. This follows Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Lahey Hospital merging this year into the very big Beth Israel Lahey Health, and Rhode Island-based CVS taking over health insurer Aetna. And huge Partners HealthCare, the Boston-based hospital and physicians network group (Massachusetts General Hospital, etc.), made a run this year at taking over Rhode Island-based Care New England. And the latter outfit was in failed talks to merge with Lifespan, a merger that economics might still force – to be followed by that merged creature being eaten by a Boston group, producing a flock of golden parachutes for redundant executives?

The economics of the health-care business mean that there will be more such mergers. Big will get bigger. This may include Partners coming back to Rhode Island to try to gobble up Care New England or Lifespan or both. Or maybe Beth Israel Lahey Health will try to invade the Ocean State.

With the huge economic power – especially pricing power – and lobbying clout of the new insurance behemoths, state regulators will have their hands full trying to regulate them. Still, the merger, which would affect several million New England customers and their families, would create an entity with impressive bargaining weaponry to curb the very high prices enabled by the size and global prestige of the hospital behemoths. So let ‘em merge.

The past and future of young people in politics

The replica of the U.S. Senate Chamber in the Edward M. Kennedy Institute. in Boston

In the following Q&A, New England Journal of Higher Education Executive Editor John O. Harney asks Mary K. Grant, president of the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate, about the institute’s work connecting postsecondary education to citizenship and upcoming elections.

(Last month, NEJHE posted a similar Q&A with Nancy Thomas, director of the Institute for Democracy & Higher Education at Tufts University’s Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life.)

Harney: What did the 2016 and 2018 elections tell us about the state of youth engagement in American democracy?

Grant: We are seeing a resurgence of interest in civic engagement, activism and public service among young people. From 2014 to 2018, voter turnout among 18- to 29-year-olds increased by 79%, the largest increase among any group of voters.

The 2016 election was certainly a catalyst for galvanizing renewed interest. Since 2016, we have seen increases in people being more engaged in organizing platforms, messages and movements to motivate their peers and adults. The midterm elections brought a set of candidates who were the most diverse in our history, entering politics with urgency and not “waiting their turns” to run for office. One of the most encouraging findings was that those who felt most frustrated were more likely to vote.

While young-voter turnout in the 2018 election was historically high, it was still just 31% of those eligible to vote. Democracy depends on the voice of the people. And a functioning democracy depends on participation, particularly in polarized times. Senator Kennedy said “political differences may make us opponents, but should never make us enemies.” He envisioned the Edward M. Kennedy Institute as a venue for people from all backgrounds to engage in civil dialogue and find solutions with common ground.

As a nonpartisan, civic education organization, the institute’s goal is to educate and engage people in the complex issues facing our communities, nation and world. Since we opened four years ago, we have had more than 80,000 students come through our doors for the opportunity to not only learn how the U.S. government works, but also to understand what civic engagement looks like. All of us at the Kennedy Institute see how important it is to give young people a laboratory where they can truly practice making their voices heard and experience democracy; our lab just happens to be a full-scale replica of the United States Senate Chamber.

Harney: How else besides voting do you measure young people’s civic citizenship? Are there other appropriate measures of activism or political engagement?

Grant: Voter turnout is one measure, but civic engagement is needed every day. Defined broadly, activism and civic citizenship are difficult to measure. We engage in our local, state and national communities in so many ways.

Our team at the institute values reports like “Guardian of Democracy: The Civic Mission of Schools” that discuss how the challenge in the U.S. is not only a lack of civic knowledge, but also a lack of civic skills and dispositions. Civic skills include learning to deliberate, debate and find common ground in a framework of respectful discourse, and thinking critically and crafting persuasive arguments and shared solutions to challenging issues. Civic dispositions include modeling and experiencing fairness, considering the rights of others, the willingness to serve in public office, and the tendency to vote in local, state and national elections. To address the critical issues and make real social change, we need a better fundamental understanding of how our government works. And we need better skills for healthy, respectful debate

Harney: What are the key issues for young voters?

Grant: The post-Millennial generation is the most racially and ethnically diverse generation in our history. Only 52% identify as non-Hispanic whites. As they envision their future livelihoods in an increasingly automated workplace, they are concerned about climate change and how related food security may affect the sustainability of daily life and they are concerned about income inequality, student debt, gun violence, racial disparities, and being engaged and involved in their communities.

The institute’s polling data indicated that interests for 18-34-year-olds were reflective of society as a whole, but gun rights and gun control, education and the economy would be among the most important as they are deciding on congressional candidates in the next election.

Young people are focused on the complex global issues that concern us all but with added urgency. A Harvard Institute of Politics Youth Poll this spring found that 18-29-year-old voters do not believe that the baby boomer generation—especially elected officials—“care about people like them.” And, they expressed concern over the direction of the country.

Harney: Are there any relevant correlations between measures of citizenship and enrollment in specific courses or majors?

Grant: In a democracy, we need all majors. And more importantly, we need students and graduates to know how to work together. In a global economy, people in the sciences, business and engineering work right next to people in the fields of social sciences. I had the privilege of leading two of the finest public liberal arts college and universities in the country. I am a firm believer that regardless of disciplinary area, problem-solving requires us to ask questions, to be curious and open-minded, to think critically and creatively, incorporate a variety of viewpoints and work in partnership with others. We need to understand how you take an idea, move it along and make it into something that can improve the common good.

Harney: Are college students and faculty as “liberal” as “conservative” commentators make them out to be?

Grant: From my own work in higher education, I can say that there is diversity of perspectives and viewpoints on college campuses, which is encouraging and exciting. Liberals and conservatives are not unique in the ability to hold on quite strongly to their own viewpoints. Anyone who has ever witnessed a group of social and natural scientists discuss research methodologies can attest to that. We all need to learn how to listen to ideas other than our own

Harney: What are ways to encourage “blue-state” students to have an effect on “red-state” politics and vice versa?

Grant: Part of the country’s challenge in civil discourse is that we stop listening or we are listening for soundbites to which we overreact. One of the most important skills that we can develop is the ability to listen actively. It’s truly remarkable what can happen when students have an opportunity to get to know and work and learn with their peers across the country and around the world

What we’re finding in our programs is that people are hungering for conversation, even on difficult matters. It’s similar to the concept of creating spaces on college campuses where you can intentionally connect with people. This coming fall, we’re using an award that we earned from the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania to pilot a program called “Civil Conversations.” The program is designed to help eighth through 12th grade teachers develop the skills necessary to lead productive classroom discussions on difficult public policy issues. We’re starting in Massachusetts and plan to expand to all the blue, red and purple states.

And for those coming to the institute, we convene diverse perspectives through daily educational and visitor programs where people can talk with and listen to others who might be troubled or curious about the same things you are. Our public conversation series and forums bring together government leaders with disparate ideologies and from different political parties who are collaborating on a common cause; we host special programs that offer insight into specific issues and challenges facing communities and civic leaders, and what change-makers are doing about it.

Harney: What role does social media play in shaping engagement and votes?

Grant: Social media have fundamentally changed not only how we get our information, but how we interact with each other. According to a Harvard Institute of Politics Youth Poll, more than 4-in-5 young Americans check their phone at least once per day for news related to politics and current events.

As social media reaches more future and eligible voters, and when civic education is lacking, those who depend on social media platforms are at risk of consuming inaccurate information. This underscores not only the need for robust civic education programs, but also those in media literacy.

Harney: How can colleges and universities work together to bolster democracy?

Grant: Anyone who spends time around young people or on a college campus feels their energy and can’t help but come away with a renewed sense of hope. Colleges can continue to work together and advocate for unfettered access to higher education for students in all areas of the country. More specifically, they can engage with organizations like Campus Compact, a national coalition of more than a thousand colleges and universities committed to building democracy through civic education and community development.

Harney: How will New England’s increased political representation of women and people of color affect real policy?

Grant: The increasingly diverse representation helps to broaden and deepen the range of perspectives, ideas and viewpoints that influence public policy. There is also a renewed energy that is generated and it encourages next generation leaders to get involved, run for office, work on campaigns and make a difference in their communities. The institute has held several Women in Leadership programming events that highlight the lack of gender equity and racial diversity in public office and provide opportunities for women to network and learn more about the challenges and the opportunities.

Harney: Do young voters show any particular interest in where candidates stand on “higher education issues” such as academic freedom?

Grant: Students may not be focused on “higher education issues,” per se, but they do have a lot to say about accessibility and affordability. This generation is saddled with an enormous amount of student loan debt. That is certainly one of their greatest concerns, particularly when it comes to the 2020 presidential race.

Academic freedom is important in making colleges and universities welcoming to the exchange of differing ideas, which is a bedrock of democracy. As a former university chancellor, I believe that it is essential to create an environment where we welcome a diversity of opinion. We need to model the ability to listen to and consider viewpoints that may be very different from our own. We need to show students that we can sit down with people who think differently, find common ground, and even respectfully disagree. That’s a key part of what the Edward M. Kennedy Institute is all about.

Investigating American identity

The gallery, part of the famous prep school in Exeter, N.H., says the show “features provocative works by Becky Alley and Melissa Vandenberg, who use common domestic items to explore themes of patriotism, war, and commemoration in our current cultural environment. Whether tongue-in-cheek, or an outright adverse critique, the artists focus on American identity, and our relationship to what we believe and why.’’

Gerald Mallon: Devotion and death in Vietnam

Mr. Mallon is at the left, with the M-16 and side arm. He wrote that the Marine at the right “had taken a couple of rounds in his pelvis and had his guts in a bag the next time we met, in St. Albans Naval Hospital (in New York). He weighed about 90 pounds and looked like a skeleton. I can't remember his name but he was eventually healed, gained some weight and was retired.’’

Mr. Mallon wrote: “The smoke is from napalm - this is the single most terrifying weapon I've ever witnessed. I was in Japan (106th Army Hospital Yokosuka) down the hall from the burn ward...that was almost unbearable to see and imagine the pain involved. No matter how f— up you were - there was always someone worse off.’’

I met Cpl. Richard Clark Abbate in early January 1968, when the 3rd Battalion, 27th Marines was formed at Camp Pendleton to be deployed to Vietnam. Richard, myself, L/Cpl. Richard Belcher and PFC Gary Trott constituted a gun team with the 1st Platoon of M “Mike” Company. As team leader, Richard was responsible and caring in executing his duties. He was older, married and had been in the Corps longer than any of us. As we served together, sharing the hardship of Vietnam, we came to like him as a friend and respect him as a leader.

On May 18, at 930 we were airlifted out by helicopter to join a battle that had developed as a result of a spoiling attack code-named Operation Allen Brook. On May 17 India Company had encountered strong enemy forces on Go Noi Island. It was not truly an island, but the monsoons would flood the Ky Lam, Thu Bon, Ba Ren, and Chiem Son rivers and isolate it. It was a staging area for elements of three Viet Cong (VC) battalions and a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regiment building up for an attack on Da Nang. It took about 20 minutes to fly from Cau Ha Base Camp to Go Noi Island. Upon landing, we could hear explosions and see the tracers of rifle and machine-gun fire. Mortar rounds were coming in on our direct front. Our platoon commander told us to drop our extra gear, get down and move to the front. Enemy fire was relentless, hot and heavy. The Landing Zone (LZ) was in a defilade with a river at our back so we began to crawl to the “sound of the guns.” Our company was spread out in an area that was exposed and in front of a tree line with only paddy dikes, scrub and elephant grass for cover.

We advanced into a hail of rifle and machine-gun fire, rocket-propelled grenades and mortar fire from well-concealed bunkers, and we were pinned down by the withering fire from behind a paddy dike. The cacophony was intense and the adrenaline shock of combat surreal in its intensity. The gunfire and flying shrapnel a foot above ground were so concentrated that getting up and moving meant certain death. Marines lay in front of us – dead and dying. Despite repeated attempts, we made little headway against the enemy defenders fighting from the bunkers. Unable to advance or withdraw, we called for 105mm artillery and 81mm mortar fire on the enemy positions in the tree line. We swept supporting fire swept back and forth, with it landing within 50 yards of our lines.

Over the next several hours I fired back and forth, saturating the tree line. My M-60 machine gun began to smoke and developed a feed malfunction. We sent our ammo humper, Gary Trott, back to get more ammunition, water and another barrel for the gun. Abbate and Belcher covered me as I crawled forward to reach a critically wounded Marine, PFC Donald Byron Jones, about 15-20 yards to our right front. He had been shot through the chest and was lying on his back in an exposed position. I reached him, grabbed his ankle and rolling on my side tried repeatedly to drag him, but his utility belt with the canteens attached dug into the sand and I couldn't move him. Jones was turning blue and choking, his eyes staring blankly into oblivion. I got over him and used two fingers to clear his mouth so that he could breathe. That was when Richard appeared and began to take off the utility belt by kneeling over him between Jones’s legs. I looked at Richard, saying nothing, and began to apply a pressure bandage to Jones’s chest wound. Richard was about a foot or two away from me to my left side. I struggled to focus my attention on Jones, blocking out everything else.

It felt like a baseball bat slamming me when the bullet hit. It went through my right elbow, spinning me around, and lodging in my upper left arm. Blood seemed to explode from Richard’s face as he pitched forward. He died instantly. Disoriented, I lay there for the next hour or so talking to Jones, trying to reassure him as he slowly choked to death. I slowed the bleeding from my elbow by tying a makeshift tourniquet and putting two fingers into the gaping hole in my joint. I had blood on my chest from the wound in my left arm, and was breathing tentatively: I thought that I had been shot in the chest and feared that I would choke to death like Jones. I made the usual bargain with God to save me. Hearing the roar of jets, I looked over my right shoulder. Two planes flying parallel to our lines seemed to peel off as four canisters of napalm, tumbling wildly, hit the tree line and exploded in a huge fireball. The napalm was close enough that I felt its heat on my face. I could taste the acrid vomit in my mouth and feared that I might burn to death in the next pass, but the fire’s volume subsided.

Dazed and weak, I was grabbed by the shoulders, jerked to my feet and half dragged to the LZ. My wounds were bandaged, morphine administered, and I was led to a waiting Medivac. Before they could load me and another casualty they had to get rid of two dead Marines to make room. The crewmen lifted a poncho and two bodies rolled out like nothing special. It was over for them and it didn’t matter anymore. The helicopter lifted off and soon I arrived nauseated and shaking at a surgical unit in Da Nang – my ordeal over.

That day still echoes in my memory. I’ve reflected on the randomness of death and how lucky I’d been. After all, the bullet that killed Richard had passed within inches of my face, sparing me.

I’ve always felt deep regret for Richard’s death. I should have known that he would come to help me because that was the Marine and man he was. I often replay the events of that day, feeling the ache of having lost a friend. I wonder what life would have held in store for Richard and our other fallen comrades if they hadn’t died in Vietnam, and I feel a deep sadness when thinking of their stolen futures. I don’t know if there were worse places to be than where we fought, but I am proud to have been with “Mike” Company on that day. Every Marine in 3/27 still remembers the brothers we left behind. Richard was, and is, my brother and I miss him even now. He was one of the finer men among the Marines I have known. War is fearful, dirty and brutal but my life’s trajectory has been set by the experience…

“Through our great good fortune, in our youth are hearts were touched by fire.”

-- Oliver Wendell Holmes

In the fighting on Go Noi Island, the four companies of 3/27 lost 172 dead, with another 1,124 wounded in action. Richard Clark Abbate was one of six Marines from M Company killed in action on May 18, 1968. Enemy casualties during Operation Allen Brook were 1,017 killed and three captured. {how many wounded?} The battle at Go Noi Island remains one of most harrowing and sanguinary combat operations in Vietnam but it eliminated any direct threat to Da Nang.

“This is my commandment, that ye love one another as I have loved you. Greater love hath no man than this; that he lay down his life for his friends.”

-- John 15: 12-13

Gerald (Jerry) Mallon lives in Michigan. He arrived in Vietnam a private first class and was promoted to lance/corporal after being shot.

He’s a fellow member of an email group including New England Diary editor Robert Whitcomb.

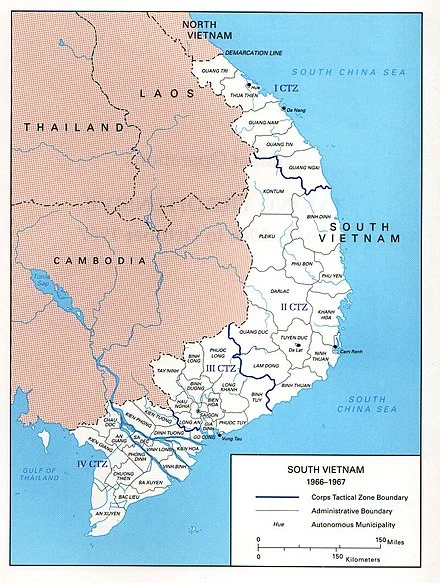

Open field fighting in Vietnam.

Da Nang, referenced in this essay, is on the ocean toward the upper right.

James P. Freeman: Hyannis's Famous Baxters succeed on sea and shore

— Photo by James P. Freeman

“As the son of a son of a sailor

I went out on the sea for adventure

Expanding the view of the captain and crew

Like a man just released from indenture”

-- Jimmy Buffet, “Son of a Son of a Sailor” (1977)

With thick fog lifting off a placid morning harbor over a pleasant Memorial Day weekend, Sam Baxter laughed at recalling a vivid memory he would just as soon forget.

Dressed for the sun and armed with a window-cleaner squeegee on a poll, he was clearing off 18 moisture-laden picnic tables on the patio at Baxter’s Fish N’ Chips, when, pausing for a moment, the thought struck him. “I used to do this on my great uncle’s boat,” he said, wincing. The vessel was, in actuality -- a black and white photo confirms -- a ferry boat named Gov. Brann that used to make excursions to and from Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard. In the 1970s it was converted into a floating ramshackle seafood courtyard with tables and benches and docked against the restaurant. Grueling drudgery for a youngster, it was Sisyphean work. But now, smiling, with the Gov. Brann long gone, Baxter admitted, “I like this better.”

Life has never been better at Baxter’s.

For one hundred years there has a been a business bearing the Baxter name at the end of Pleasant Street, just off Main Street in Hyannis, the largest of seven villages comprising the Town of Barnstable. Today’s iteration of commerce sits on pilings -- Baxter’s Wharf -- nestled within the innermost part of the harbor that connects with Lewis Bay, which connects with Nantucket Sound. The harbor is the largest recreational-boating port and second-largest commercial fishing port on Cape Cod, behind only Provincetown.

In fact, Hyannis Harbor has played a pivotal role in regional maritime lore: In 1602, Captain Bartholomew Gosnold was the first to survey the area; in 1639, settlers from England incorporated the Town of Barnstable; in 1666, Nicolas Davis, among the first settlers, built a warehouse for oysters on Lewis Bay; and, in 1840, over 200 shipmasters established dwellings in Hyannis and salt works became an important industry.

Furthermore: In 1849, Hyannis Harbor Light was built, marking the channel in Lewis Bay; in 1854, the first railroad cars reached Hyannis, signaling increased commercial development (by century’s end the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad had rails extending to Hyannisport Wharf, which hauled many tons of coal, fish and agricultural products); and, in 1928, Joseph P. Kennedy and his wife, Rose, purchased the Malcom Cottage in Hyannisport; an adjacent residence would later become the “Summer White House” under his son John F. Kennedy.

Today, the cedar-shingled Baxter’s building, painted in the classic seaside colors of gray with white trim, is nondescript and houses the Boathouse (a private club) and Fish N’ Chips (the public restaurant). The outside looks like the kind of place that Guy Fieri might discover on Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives.

But that wouldn’t do it justice.

At Baxter’s, genetics carry more ballast than aesthetics. Once inside you will understand. Five generations of history sway fore and aft before your eyes. The ghosts in these walls call you back in time. They almost dare you to immerse yourself in a time that was simpler but, for seafaring people like the Baxters, very difficult indeed. And dangerous.

The long lineage of Baxters on Cape Cod extends way, way back.

It begins with Benjamin D. Baxter.

Born on Camp Street in West Yarmouth, in January 1833, he was one of a family of 15 children. Like many boys at the time, he went to sea when he was 12. His life is captured in an extraordinary compendium entitled Hyannis Sea Captains. In 1939, author C.R. Harris wrote that the book was written as the last of the “deep water men of Hyannis” were leaving the good earth. And with them, he warned, “was going the record of adventure and achievement of … sturdy characters who were pioneers in the world of commerce through the medium of transportation by sail.” Baxter fit that description and was, by all accounts, a remarkable mariner.

Captain Baxter commanded the transport Promethus as well as two gunboats, the Vedette and the Chasseun, during the Civil War. Later, in the merchant service, he commanded the ships Nearchus and John N. Cushing. For years he traded in the East Indies. At one point, writes Harris, the Cushing was dismasted in a typhoon. Baxter “managed to sail it into a river, rigged a jurymast, with his crew, and sailed it to its destination, after it had been given up for lost.”

But it was his command of the Gerard C. Tobey for which he gained further esteem and “perpetuated the fame” of the bark for his speed records. Barks (derived from the French barques) are sailing vessels with distinctive rigging (three or more masts, having the fore and main masts rigged square and only the mizzen rigged fore and aft). During the golden age of sail, in the mid-19th Century, barks were the workhouses of the sea (analogous today to Boeing 737 jets, workhorses of the air). In 1878, Baxter retrofitted the Tobey with double topgallant and main skysails, both unusual with a bark. On the first leg of one of its last voyages, it sailed from Wiscasset, Maine, to Cardiff, Wales, in 18 days. (Today’s transatlantic crossing, with engines, is about seven days.) These boats were smaller than most other ocean-going ships and could sail with fewer crew members and so were cheaper to operate. \

After 30 years at sea, Baxter retired in Antwerp, Belgium, and engaged in the ship chandlery and outfitting business. Then, in ill health, he returned to Hyannis to spend his remaining days. (At one time he had a shoe store in what is now the Hyannis Inn, 209 Main St.) He died in April 1897 and is buried in Hyannis.

Captain Baxter had four daughters and one son. Benjamin D. Baxter Jr. was born on Park Square, in the Marcus Crocker House. Junior became a stevedore and U.S. shipping master. Notably, on Nov. 4, 1904, he was appointed by the U.S. director of customs as deputy collector and inspector for the District of Barnstable. In these roles Baxter oversaw much of the maritime commerce in Hyannis. Given the circumstances, he must have seen the potential at the end of Pleasant Street. The family had been operating the dock since the early 1900s.

So he bought the property in 1919.

The next generation of Baxters -- Benjamin D. Baxter and Warren Baxter Sr. (Sam’s grandfather) -- were fixtures on the Hyannis waterfront. At first, they had a fuel depot next to the Steamship Authority that served the local fleet and by the 1940s and 1950s a thriving fish market. Then Baxter’s Fish ‘n’ Chips opened in 1957, after Sam’s grandmother had started frying local fish. The fish market closed in 1966 as supermarkets became the primary retail distribution channel. But the next year, Baxter’s Boathouse opened as a “companion bar and restaurant to the more family-friendly fish and chips half,” reported The Cape Cod Times. The only alcohol served was Budweiser on tap and vodka with cranberries. Nothing else.

Ben Baxter was a scrappy character: a tinkerer, collector and restorer. He was also a fisherman and captain. He lived in a house on the water’s edge that was built in 1898 and flooded severely by three hurricanes in 1954. Among his special talents was sailing. He befriended and raced many Kennedys, including the future president. He actually had the audacity to beat John F. Kennedy and claimed, in 1993, that he had effectively retired the Scudder Cup.

The Baxter-Kennedy relationship is as long as a generational yardarm.

Evidence abounds in the restaurant. An envelope postmarked Aug. 3, 1961, contained a thank you note from the White House and addressed to Warren Baxter. Next to it, encased in glass, is a short companion article dated Aug. 16, 1961, from Time Magazine. It reads: “Baxter’s Fish Market was standing anxiously by, awaiting the order for lobsters and fish for chowder.” President Kennedy was entertaining Lester B. Pearson, then the Canadian prime minister, at the compound.

Warren Baxter Jr. (known as “Barney,” after Barnabas was rejected), a Marine Corps veteran, and Sen. Edward Kennedy were friends and the senator would patronize the restaurant to say hello and enjoy fried clams. Sam recalls -- casually and hilariously -- one day seeing Arnold Schwarzenegger, adorned with an apron, cooking his own swordfish in the kitchen. Just another day in the office…

Both the Boathouse and Fish N’ Chips are peppered with nautical artifacts and memorabilia. The late senator’s water skis hang from the ceiling. A buoy from the movie Jaws is tucked over a gable. And a ghost in living color eerily jolts your attention: a photo of the fishing boat Andrea Gail. Several times she was docked at Baxter’s before “The Perfect Storm,” of Oct. 29-Nov. 2, 1991, in which she went down.

Today, Baxter’s is run by Sam, now 47, and his brother named, appropriately, Ben, 54.

The fifth-generation Ben Baxter just retired from the Barnstable Police Department after 34 years of service. He bears an uncanny resemblance to his captain namesake, sans beard. They share something else, too. At their core they were journeymen. One cruised the high seas while the other patrolled the highs on the streets. You can picture them at a table in the Boathouse trading salty stories over rum and ribaldry. “Aye, Aye!”

Sitting with the brothers in their second-story office overlooking the harbor, the mood and the water glisten with nostalgia as friendly currents and conversations lead to the present. The crammed space is a tangle of wires and memories. Computers, not sextants, guide navigation and operation. The family institution reflects 2019.

While fish and chips are still the most popular items with customers, today’s menu features new takes and tastes, such as gluten-free selections and salads. Years ago the old chalk board menu was replaced with an electronic one. Today’s offerings include an all-natural proprietary Bloody Cocktail Mix (don’t ask for the secret recipe, you’ll have better odds of discovering a buried treasure off Nantucket) and, of course, colorful merch.

Some things change very little.

Business opens on the second Friday in April and continues through Columbus Day. Words like “consistency” and “quality” are imperatives. The Boathouse is a private club that requires membership. (Two years ago, celebrating its golden anniversary, $50,000 in membership proceeds were donated to charity.) Maintenance and insurance can be crushing. (Hurricane Bob, on Aug. 8 1991, flooded the entire space.) Many of the 75 seasonal staff return each summer (Adriano, manager and chef, has been a mainstay for 22 years; he is considered like family.) And already the next-gen of Baxters is onboard.

Incredibly, not one dime is spent on marketing or advertising. The brothers say word of mouth suffices – along with word of boat. The harbor side of the building comes with a dock letting boaters park and get food delivered to them. As Ben says, “Docking and dining is first come first serve, on Saturday and Sunday there is usually a wait time.”

“I’ve been here full time my whole life,” Sam quips, still cheerful after all these years. The brothers hope to be serving new generations for the rest of their lives, just as previous Baxter generations have done.

“Having a family-run business for over 50 years,” Ben ruminates, “is almost unheard of nowadays. Having a business located on the property our great grandfather started a hundred years ago is even more rare. It means a lot to me.” He adds, “I want my children to be proud of their name and heritage.”

For Sam and Ben the familiar refrain needs extension. They are literally sons of a son of a son of a son of a sailor.

A shorter version of this article appears in Cape Cod LIFE, where the article first appeared.

James P. Freeman is a New England-based writer. He is a former columnist with The Cape Cod Times and New Boston Post. His work has also appeared, besides in New England Diary, in The Providence Journal, The Cape Codder, golocalprov.com, nationalreview.com and insidesources.com.

William Morgan: The tackiness of license plate grieving

America has a bizarre relationship with memory. We are obsessed with memorials. Do we really believe that one more teddy bear, cellophane-wrapped bouquet of flowers, commemorative tattoo, or one more awful sculpted bas-relief will somehow make it easier to gloss over the inexplicable deaths in a Walmart shooting or a senseless war in Iraq?

The Rhode Island license plate that honors the families of American military personnel who have been killed in service is just the latest in this superficial exploitation of grief.

There is no fee for this plate, but one needs an Official Department of Defense Report of Casualty (DD Form 1300).

Aside from evoking sympathy, being a Gold Star relative might be insurance against tickets: What police officer will fine the mom or father of a son or daughter killed in an ambush in Afghanistan?

There does seem to be a correlation between tacky remembrance and bad design. While by no means the worst of the Ocean State's specialty plates, the Gold Star issue is a minor graphic disaster.

The designers of these special plates seemed concerned only with content, with the result that most of these are embarrassing messes.

The Gold Star Family plate has the folded casket flag in the background, a seal, and the scarecrow-like Iraq War version of a battlefield memorial: helmet, assault rifle, dog tags and boots.

A license plate ought to serve only two functions: revenue and vehicle identification. Political agendas, club affiliations, and historical events should have no place on auto tags. They are distracting visually, while they often make a mockery of what they purportedly hope to remember or honor.

Would this commemorative plate appeal to the mothers of Eric Garner or Michael Brown or Emmett Till?

If one's son/husband/wife/father/mother/brother/sister were killed in a secret operation in some godforsaken place like Niger, would a Gold Star Family license plate be the best way to ensure that these fallen warriors are not forgotten? Is this the most dignified way to remember them?

Princeton University has a tradition of placing a small bronze star beneath the dormitory window where an alumnus who was killed in service had lived. I taught at that university, and in my time there I could not pass by one of these simple, quiet reminders without being moved at the thought of such sacrifice.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian, essayist and author of many books.

Franklin's lightning rod and Mass. earthquakes

“When Benjamin Franklin {a Boston native who moved to Philadelphia} invented the lightning-rod, the clergy, both in England and America, with the enthusiastic support of George III, condemned it as an impious attempt to defeat the will of God. For, as all right-thinking people were aware, lightning is sent by God to punish impiety or some other grave sin—the virtuous are never struck by lightning. Therefore if God wants to strike any one, Benjamin Franklin [and his lightning-rod] ought not to defeat His design; indeed, to do so is helping criminals to escape. But God was equal to the occasion, if we are to believe the eminent Dr. Price, one of the leading divines of Boston. Lightning having been rendered ineffectual by the 'iron points invented by the sagacious Dr. Franklin,' Massachusetts was shaken by earthquakes, which Dr. Price perceived to be due to God's wrath at the 'iron points.' In a sermon on the subject he said, 'In Boston are more erected than elsewhere in New England, and Boston seems to be more dreadfully shaken. Oh! there is no getting out of the mighty hand of God.' Apparently, however, Providence gave up all hope of curing Boston of its wickedness, for, though lightning-rods became more and more common, earthquakes in Massachusetts have remained rare.”

― Bertrand Russell (1872-1970), from "An Outline of Intellectual Rubbish: A Hilarious Catalogue of Organized and Individual Stupidity''

Retail outlet business fading in N.E.

Street scene in 2012 during a street fair in Freeport, Maine, perhaps New England’s most famous retail outlet town. Business has been sliding since then.

— Photo by Dirk Ingo Franke

—

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Quite a few New England towns, such as Freeport (home of L.L. Bean) and Kittery, Maine, Westbrook, Conn., and Wrentham, Mass., have long positioned themselves as venues for higher-end retail outlets for national brands and gotten a hell of a lot of tax revenue from them. But Amazon and other online retailers are taking big bites out of them and many stores are closing. Some of the vacant space is being rented by local stores, but paying much lower rent than the prestige national brands did.

Housing is too expensive for many people. So how much of this dead retail space can be converted to housing; and if all or most of the stores now in these outlet malls close, can they be reconfigured into latter-day, mostly residential village centers or have to be demolished?

Don Pesci: Connecticut's identity crisis

“A rose by any other name,’’ Shakespeare wrote, “would smell as sweet.’’ However, we should never forget that naming is essential. No one appreciates this more than journalists and philosophers who are in the business of correctly naming people, things and ideas.

The name “Connecticuter” (pronounced Connetta-cutter) has cropped up recently as a possible name for people who live in Connecticut.

The name Connecticut itself, like other native-American place names, presents unique difficulties because they are tongue twisters. The tongue trips over Quinnipiac College; some talking heads invariably mispronounce it. Connecticut the place was named with reference to the river that flows through it, called by native-Americans Quinnehtukqut, which means "beside the long tidal river.

People who live in Connecticut have at various times been called Nutmeggers and Connecticuters. Research director for the nonprofit Public Religion Research Institute Natalie Jackson found this locution while searching through the U.S. Government Publishing Office Style Manual. The U.S. Government Printing Office conferred that title on Connecticut in 1945, and the Merriam-Webster Dictionary lists the definition of ‘Connecticuter’ as “a native or resident of the state of Connecticut.

The chief objection to this designation, a sour-tongued cynic might say, is that the name might have been proper in 1945, but currently the state is knee-deep in debt to the tune of $60 something billion, and progressives in the state’s General Assembly are loathed to balance their accounts by cutting labor costs; therefore, any nickname that hints at cutting -- Connetta-cutter – would be highly misleading, however politically useful.

Connecticut State historian Walt Woodward has put the state on the psychiatrist’s couch and suggested that Nutmeggers may have some difficulty naming themselves because of a longstanding identity and status problem: “For people who love Connecticut, and there are a lot of people who feel an intense connection to the state, they still have trouble coming up with — what is it that we love about Connecticut? What is our unique identity? Even though Connecticut has a definite identity and it is instinctively clear to people, it is hard for them to define. All that angst about identity sometimes gets focused on what we call ourselves.” Woodward prefers to call himself a Connectican.

U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy has promised to have a chat with Hartford Courant writers about this perplexing issue. One can only hope he will not propose a bill in the Senate formally nicknaming the Nutmeg State. That would only plunge in statutory cement the state’s angst, and most of us would still be wondering who we are. Actually, Connecticut had in the past defined itself rather modestly with respect to its contiguous states. We were less showy than Massachusetts, a haven from the angst-ridden lifestyle of the average New Yorker, and we were comfortable with our non-notoriety, provided we could hang on to our wealth and dignity.

Our sour cynic above might suggest “Conner’” as an appropriate nickname. Indeed, that is what the “Nutmegger” designation initially suggested. In the good old colonial days, Nutmegger vendors from Connecticut were known to spike their loads of nutmeg with wooden nuts cunningly fashioned in the form of nutmegs, a well know and under-appreciated con. Those folk from Connecticut, traders thought, were too clever by half. So long as the people of Connecticut were clever, the name stuck. It has long since gone out of fashion, as have other Connecticut designations: “The Constitution State” and “The Provision State”, so called because Connecticut was a provider of military wares to the fledgling government of the revolutionary republic.

Connecticut’s identity crisis, it should be noted, is of recent vintage. We have during the last three decades shed our historical identity as prudent and watchful guardians of the public purse. We have leveled the political playing field between Connecticut and contiguous states, New York and Massachusetts, by instituting an income tax, thus negating our political advantage as a tax haven and cost-conscious spender in New England. And we have lost a good deal of our bad-boy cleverness, except in the anarchical-sections of our cultural political barracks, where disruptive innovation is encouraged. Public school kindergarteners in once Puritan Connecticut may now enjoy in their classrooms the company of cross-dressing males. Pretty much all business activity in the state is encumbered with regulations and taxation, and we continue to pester with crippling and punishing regulations women’s health centers that will not allow abortionists to cross their lintels.

On the other hand, there are some enduring positives. We are still a small state, relatively speaking, and no politician can through legislation alter the state’s geographical location between Boston and New York. Despite the Connecticut’s rapid political change, we may still depend upon the four seasons visiting us at their appointed times. Even though all’s not right in the world, God is still in his Heaven and, as Otto von Bismarck used to say, “God has a special providence for fools, drunkards, and the United States of America.” Despite the reductionism of modern times, the state's motto still is "Qui Transtulit Sustinet" -- He Who Transplanted Still Sustains.

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn.-based essayist.

Jill Richardson: Race is a social construct invented for domination

From OtherWords.org

When I teach about race in sociology classes, I often begin by asking students how and when the idea of race came about.

Lesson one? Race is not a biological reality — it’s a social construct.

That doesn’t mean there’s no biological basis to it at all — anyone can tell the difference between different skin tones and understand the role that genetics play in passing on traits. However, if you were to try to divide the world into discrete racial categories based on genes, you couldn’t.

Where, exactly, in North Africa would you draw the line between black people and white people? Where in Central Asia is the split between Middle Eastern or European and Asian?

The racial categories we use today were created by humans, and they unfolded as they did because of our history. When Europeans came to this continent, taking land from (and often killing) Native Americans and enslaving Africans, they needed a justification and organization for their conquest and domination. They invented race to do that job.

Just because race is not a biological reality doesn’t mean it doesn’t matter — the consequences, after all, are all too real. One person could enslave another because of it.

Why do some racial groups do better than others in America? It’s not because one is genetically or culturally superior. It’s because people of color have been systematically disadvantaged throughout American history while white people have been advantaged over them.

When I teach this, I spend a lot of time detailing how as recently as a few decades ago, government programs facilitated white families owning their own homes in segregated neighborhoods while denying people of color opportunities for home ownership.

Many of the people who were helped or harmed by these policies are still alive, and they and their descendants are still affected in their wealth, health, education, and employment.

Obviously, America has come a long way from the 1600s — or even from the 1960s. But the El Paso shooter and the policies of the Trump administration show a continuity with America’s dark past.

In the first half of the 20th Century, our immigration policies reflected the notion of a white America, limiting or prohibiting people of color from coming to this country. The El Paso shooter believed in a white America. But Trump’s immigration policies validate that idea too.

Trump isn’t against all immigrants, seeing how he keeps marrying them. And his mom is one. But his Scottish mother and Czech and Slovenian wives fit within the notion of a white America. The people targeted in the recent ICE raids do not.

My great grandparents were poor, hardworking Eastern Europeans. The generations who came after them grew up attending American schools, holding jobs, and paying taxes. There’s no reason a Honduran, Filipino, or Mexican family arriving today cannot follow the same path my family did — no reason, that is, except discrimination on account of their skin color.

If we accept that Americans are people of all races, colors, and creeds, and if we accept America as a nation made up largely of immigrants, then all people can find a place here. If there is no “us” and “them,” then “we” don’t have to worry about “them.”

We can’t ignore the white supremacy baked into anti-immigrant notions that see people of color as un-American or as threats to America. When some advocate hateful ideas, others will act on them with violence.

Jill Richardson, a sociologist, is a columnist for OtherWords.org.

A project of the:

IPS logo

ABOUT

ARCHIVE

SYNDICATE

This is America: Make it an AK-47

“Carrot and Stick’’ (wood, paint), by Steve Novick, in his show “Approximation,’’ at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., Aug. 18-Nov. 10.

Exploring his Italian ancestry

Work by J.P. Terlizzi, in his show “Descendants,’’ a the Rhode Island Center for Photographic Arts, Providence, through Sept. 11.

The center says:

“‘Descendants’' explores the origins of personal identity as it relates to the artist’s Italian ancestry and is an attempt to preserve the artist’s past, connecting and honoring the generations that came before. Curiosity surrounding how the past relates to the present, and how the bloodline passed down through generations represents the passage of time are central to JP’s presentation of family and familial bonds. Terlizzi utilizes a digital composite photograph of his ancestors and then incorporates his own blood specimens onto microscope slides, stitching them on the image to create new family portraits as an archive and memorial.

Chris Powell: More realism needed in debating how to curb mass shootings in our crazy country

AK-47 Type 3A with ribbed stamped-steel magazine

Protesting President Trump's massacre condolence tour when it reached Dayton last week, a man held a sign reading, "You are why." But as objectionable as the president's demeanor often is, the protester's sign was just politically partisan wishful thinking.

For while the mass murderer in El Paso appears to have hated the illegal immigrants often disparaged by the president, the one in Dayton appears to have been a leftist, a supporter of Antifa and Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, as was the crazy who shot up the Republican congressional baseball team's practice in Arlington, Va., two years ago

On the weekend of the El Paso and Dayton massacres there were 50 shootings in Chicago, a city long under Democratic management in a heavily Democratic state. A few days ago two people were shot together in Hartford, and nearly every day produces shootings not just in Hartford but also in Bridgeport and New Haven, where there are hardly any Republicans. Shootings are now the way of life in Democratic urban America, and politicizing those shootings would impugn the president's most strident critics.

Good if the latest massacres induce Congress to pass legislation increasing background checks for gun purchases. But most purchases -- those made through licensed dealers -- already require background checks. The exceptions are guns sold privately, and these are seldom used in mass shootings. Indeed, most guns used in mass shootings have been obtained legally after background checks, and there does not seem to be anything in the records of the perpetrators in El Paso and Dayton that would have disqualified them from their guns. Most crazies are not criminals before their mass murders

Good also if Congress passes "red flag" legislation, establishing procedures for challenging a gun owner's fitness -- provided, of course, the procedures include sufficient due process. But a "red flag" law can work only if a gun owner advertises his guns, and few gun owners bent on mayhem are likely to do that.

Maybe large-capacity ammunition magazines should be prohibited, but empty magazines are easily replaced in two or three seconds

That leaves outlawing "assault weapons." But how are those to be defined other than by their ability to fire a series of bullets with repeated trigger pulls but without immediate reloading? Except for barrel size there is little difference in technology between "assault weapons" and ordinary handguns

For nearly all modern guns except shotguns are "semi-automatic." Fully automatic guns, guns that spray bullets by a single pull and hold of the trigger, are the only real military guns and their possession is already highly restricted. Few are in civilian hands.

Semi-automatic has been the norm with civilian guns since Connecticut's Sam Colt perfected the revolver almost two centuries ago.

As a practical matter an "assault weapon" is just any rifle that scares somebody.

So nearly all modern guns in civilian possession can be called "assault weapons," and if semi-automatic guns are to be outlawed, nearly all guns in civilian possession will be illegal. That would require more than tinkering with the Second Amendment. It would require repeal and confiscation.

The country is in a tough spot. It is full of both crazies and guns and the issue is far more difficult than its partisans let on. Whatever should be done, it will have to start with more clarity and honesty than the debate has provided so far.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

At a tabloid in the summer of '69

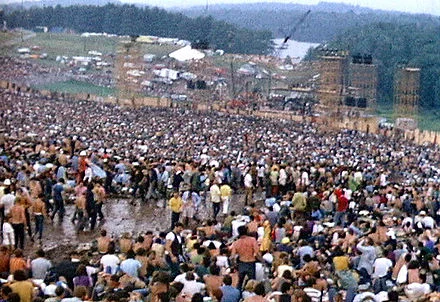

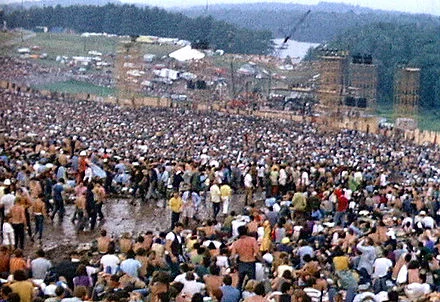

Fun in the mud in Woodstock

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Some of the elderly commentariat has turned to the 50th anniversary of “Woodstock,’’ that Aug. 15-Aug 18, 1969 musicale and bacchanal in Bethel, N.Y. The spectacle, which produced many, many photos of attendees in the mud as they listened to rock stars, has of course become listed as one of the great epochal events of the “Sixties’’ (which as a cultural phenomenon might be said to have begun after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, on Nov. 22, 1963, and ended with Richard Nixon’s resignation on Aug. 8, 1974). I can well imagine how boring many Millennials must find stories about Woodstock.

Woodstock, which happened at the tail end of Sixties prosperity, didn’t change much of anything. The late adolescents and young adults there moved on to get mostly conventional jobs and to raise families. Whatever the alleged “peace and love’’ elements, the “Woodstock Generation’’ turned out to be perhaps greedier and more self-absorbed, and less civic-minded, than their parents’ generation, if less bigoted on such matters as race and sexual preference and more open to equality for women. Still, Woodstock itself was admirably affable and peaceful, friends who were there told me. I suspect that some Boomers’ frequent references to the spectacle bespeak a desire to place themselves in a comforting cohort, and in history, a kind of anchoring, as they move into their last innings.

I am in that generation. Still in college, I had a summer job as a news assistant at the now long-dead tabloid the Boston Record American. I had no plans to go into journalism. The job, in the Record’s mostly unairconditioned (fans and salt tablets instead) but beautiful stone building in downtown Boston, was a lifeline for me when another summer job fell through at the last minute.

When word arrived in the smoky newsroom about “Woodstock,’’ the general reaction by the mostly gruff and Irish-and-Italian-American staff was that the event was just another stretch of idiocy by spoiled kids. “Why aren’t they working?” The reporters seemed to be far more interested in the continuing drama of what had come to be called simply “Chappaquiddick’’ on July 18 of that busy summer, in which Sen. Edward Kennedy drove off that infamous bridge, resulting in the drowning of his young woman passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne. (When I asked my father what Kennedy was up to, he replied: “He was looking for a soft dune.’’)

And my news room colleagues didn’t even seem to be very interested in the moon landing, which had come on July 18. Nothing could beat an old-fashioned scandal involving Massachusetts’s Royal Family.

Warming seas

Welcome to Cape Cod, circa 2100?

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

'I read the other week that the water temperature at an observation buoy in Nantucket Sound was a tropical 77 degrees! That recalled a new study by the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, in Portland, reporting on how “marine ecosystems around the world are experiencing unusually high ocean temperatures more frequently than researchers previously expected. These warming events, including marine heatwaves, are disrupting marine ecosystems and the people who depend on them.’’ The Gulf of Maine, by the way, is warming faster than 99 percent of the world’s ocean water. That’s rapidly changing marine life there.

To read more on the report, please hit this link.