Boston’s housing-creation Drought worsens

Excerpted and edited from a Boston Guardian article.

After booming during Mayor Marty Walsh’s years, construction of new apartments, condos and homes in Boston has plunged.

The drop-off began in mid-2022 as the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates to battle inflation and as Boston Mayor Michelle Wu shifted city housing policy away from her predecessor’s pro-growth approach.

During her first months in office, Wu unveiled an ultimately unsuccessful plan to bring back a form of rent control, while also vowing to hike affordable housing and energy efficiency for new housing developments.

And while Marty Walsh had focused on boosting the volume of new housing produced by encouraging private-sector development, Wu refocused city efforts on building more public housing.

Now the decline appears to be gaining speed, with the city’s Building Department issuing just building permits for just 72 new housing units in March, according to a review of city records….

This caps a dismal, seven-month run in which housing starts in Boston have fallen to their lowest levels since at least 2018.

Lineage in history

“material research,’’ by Alia Farid, at her show at Johnson-Kulukundis Gallery, in Cambridge Mass.

The gallery explains:

The show displays “large, greenish-blue resin panels embedded with family photographs, spiritual charts, and historical documents. The work explores themes of lineage, memory and geopolitical histories, reflecting personal and collective identities shaped by migration, cultural traditions and archival storytelling. The image below reflects small, irregularly shaped blue ceramic fragments resting on a textured greenish surface, casting soft shadows.’'

Chris Powell: Elections are insecure without proof of citizenship; then why the extra grades?

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Having fallen in love with executive orders even more than his predecessor did, President Trump is coming down with a bad case of megalomania. He has little authority to command the states to follow any particular election procedures, as he presumed to do with another executive order the other day. Congress can do that but not the president on his own.

Connecticut Secretary of the State Stephanie Thomas properly called the order “another unlawful and unconstitutional overreach into our electoral processes."

But as a matter of policy in regard to the order's most important component, Trump is right and Thomas is wrong.

Trump wants people to be required to provide proof of citizenship when registering to vote. While the law requires citizenship for voting in federal and state elections, Connecticut and most other states don't require proof of it -- a birth certificate, passport, or naturalization document. Registrants are required only to affirm their citizenship under penalty of perjury.

Of course few officials check.

Thomas echoed the weak objections to requiring proof of citizenship for voter registration: Many people don't have or have misplaced their birth certificates. Many don't have passports. Many have changed their names but have not updated their identification documents.

While these are fair concerns, conscientious people can address them easily enough, even as government already often requires people to produce identification for purposes far less important than voting.

These days in Connecticut even grizzly old graybeards are being ‘‘carded" in the supermarket when buying beer. In Connecticut you can't legally drive a car without a driver’s license and the car must be registered with the state and covered by insurance. Those things require producing identification. So does boarding an airplane. Such requirements are inconveniences, especially for the poor people Democrats prattle about, but there are good reasons for them and Secretary Thomas hasn't proposed repealing them.

Being a good citizen requires some effort. It is not too much to ask people to maintain proof of citizenship in the face of the devaluation of citizenship that was undertaken by previous national administrations and continues to be advocated by most Democratic officials in Connecticut, whose belief in illegal immigration has made the state a “sanctuary" obstructing enforcement of immigration law.

Many Democrats in Connecticut and elsewhere advocate letting non-citizens vote, at least in municipal elections. Indeed, in 2022 New York City, a Democratic bastion and ‘‘sanctuary city," enacted an ordinance to let non-citizens vote in city elections, contradicting New York's state constitution. Last month the state's Supreme Court nullified the ordinance.

Secretary Thomas says Connecticut already has “strong and secure elections," but that claim is undermined by recent election fraud involving prominent Democrats in Bridgeport and Stamford. Many municipalities in Connecticut seem unable to tabulate elections fully in less than two or three days, leaving plenty of room for fiddling with close results when observers have gone to sleep.

Republicans in Congress support legislation to require proof of citizenship for voting, but it will be blocked by Democrats in the Senate, just as similar legislation would be blocked in Connecticut by the big Democratic majority in the General Assembly.

As long as Connecticut refuses to confirm the eligibility of voters, its elections won't really be secure.

WHY THE EXTRA GRADES?: A state legislator has noticed the disaster of social promotion in Connecticut's public schools. State Rep. Tami Zawistowski (R-East Granby) has introduced a bill to require high-school graduates to show they can read at an eighth-grade level.

Of course there are 12 grades in public education, but even the low bar proposed by Zawistowski may terrify educators. Her bill might have a better chance if it linked graduation to a fourth-grade reading level.

Zawistowski's honesty about education raises a good question: Whether the standard is to be eighth grade or fourth grade, why is Connecticut bothering with all those extra grades?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Shifting roles of technology’

“Thin Ice,’’ by Joseph Smolinski, at Real Art Ways, Hartford, Conn., through April 23.

His Web site says that Mr. Smolinski is a multidisciplinary artist and educator who lives and works in New Haven. “His practice questions the shifting roles of technology within communication networks, energy and oil companies, and the industrial agricultural infrastructure, which indelibly shape the so-called natural environment.’’

Jennifer Tucker: Trump opens new front in culture wars

The Smithsonian Building (aka “The Castle”), in Washington.

Jennifer Tucker is a professor of history at Wesleyan University.

She does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article, except for the picture above, is from The Conversation.

MIDDLETOWN, Conn.

I teach history in Connecticut, but I grew up in Oklahoma and Kansas, where my interest in the subject was sparked by visits to local museums.

I fondly remember trips to the Fellow-Reeves Museum, in Wichita, Kansas, and the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. A 1908 photograph of my great-grandparents picking cotton has been used as a poster by the Oklahoma Historical Society.

This love of learning history continued into my years as a graduate student of history, when I would spend hours at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum learning about the history of human flight and ballooning. As a professor, I’ve integrated the institution’s exhibits into my history courses.

The Trump administration, however, is not happy with the way the Smithsonian Institution and other U.S. museums are portraying history.

On March 27, 2025, the president issued an executive order, “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” which asserted, “Over the past decade, Americans have witnessed a concerted and widespread effort to rewrite our Nation’s history, replacing objective facts with a distorted narrative driven by ideology rather than truth. Under this historical revision, our Nation’s unparalleled legacy of advancing liberty, individual rights, and human happiness is reconstructed as inherently racist, sexist, oppressive, or otherwise irredeemably flawed.”

Trump singled out a few museums, including the Smithsonian, dedicating a whole section of the order on “saving” the institution from “divisive, race-centered ideology.”

Of course, history is contested. There will always be a variety of views about what should be included and excluded from America’s story. For example, in my own research, I found that Prohibition-era school boards in the 1920s argued over whether it was appropriate for history textbooks to include pictures of soldiers drinking to illustrate the 1791 Whiskey Rebellion.

But most recent debates center on how much attention should be given to the history of the nation’s accomplishments over its darker chapters. The Smithsonian, as a national institution that receives most of its funds from the federal government, has sometimes found itself in the crosshairs.

America’s historical repository

The Smithsonian Institution was founded in 1846 thanks to its namesake, British chemist James Smithson.

Smithson willed his estate to his nephew and stated that if his nephew died without an heir, the money – roughly US$15 million in today’s dollars – would be donated to the U.S. to found “an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.”

The idea of a national institution dedicated to history, science and learning was contentious from the start.

In her book The Stranger and the Statesman, historian Nina Burleigh shows how Smithson’s bequest was nearly lost due to battles between competing interests.

Southern plantation owners and western frontiersmen, including President Andrew Jackson, saw the establishment of a national museum as an unnecessary assertion of federal power. They also challenged the very idea of accepting a gift from a non-American and thought that it was beneath the dignity of the government to confer immortality on someone simply because of a large donation.

In the end, a group led by congressman and former president John Quincy Adams ensured Smithson’s vision was realized. Adams felt that the country was failing to live up to its early promise. He thought a national museum was an important way to burnish the ideals of the young republic and educate the public.

Today the Smithsonian runs 14 education and research centers, the National Zoo and 21 museums, including the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which was created with bipartisan support during President George W. Bush’s administration.

In the introduction to his book Smithsonian’s History of America in 101 Objects, cultural anthropologist Richard Kurin talks about how the institution has also supported hundreds of small and large institutions outside of the nation’s capital.

In 2024, the Smithsonian sent over 2 million artifacts on loan to museums in 52 U.S. states and territories and 33 foreign countries. It also partners with over 200 affiliate museums. YouGov has periodically tracked Americans’ approval of the Smithsonian, which has held steady at roughly 68% approval and 2% disapproval since 2020.

Smithsonian in the crosshairs

Precursors to the Trump administration’s efforts to reshape the Smithsonian took place in the 1990s.

In 1991, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which was then known as the National Museum of American Art, created an exhibition titled “The West as America, Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820-1920.” Conservatives complained that the museum portrayed western expansion as a tale of conquest and destruction, rather than one of progress and nation-building. The Wall Street Journal editorialized that the exhibit represented “an entirely hostile ideological assault on the nation’s founding and history.”

The exhibition proved popular: Attendance to the National Museum of American Art was 60% higher than it had been during the same period the year prior. But the debate raised questions about whether public museums were able to express ideas that are critical of the U.S. without risk of censorship.

In 1994, controversy again erupted, this time at the National Air and Space Museum over a forthcoming exhibition centered on the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima 50 years prior.

Should the exhibition explore the loss of Japanese lives? Or emphasize the U.S. war victory?

Veterans groups insisted that the atomic bomb ended the war and saved 1 million American lives, and demanded the removal of photographs of the destruction and a melted Japanese school lunch box from the exhibit.

Meanwhile, other activists protested the exhibition by arguing that a symbol of human destruction shouldn’t be commemorated at an institution that’s supposed to celebrate human achievement.

Republicans won the House in 1994 and threatened cuts to the Smithsonian’s budget over the Enola Gay exhibition, compelling curators to walk a tightrope. In the end, the fuselage of the Enola Gay was displayed in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. But the exhibit would not tell the full story of the plane’s role in the war from a myriad of perspectives.

Trump enters the fray

In 2019, The New York Times launched the 1619 project, which aimed to reframe the country’s history by placing slavery and its consequences at its very center. The first Trump administration quickly responded by forming its 1776 commission. In January 2021, it produced a report critiquing the 1619 project, claiming that an emphasis on the country’s history of racism and slavery was counterproductive to promoting “patriotic education.”

That same year, Trump pledged to build “a vast outdoor park that will feature the statues of the greatest Americans to ever live,” with 250 statues to mark the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

President Joe Biden rescinded the order in 2021. Trump reissued it after retaking the White House, and pointed to figures he’d like to see included, such as Christopher Columbus, George Washington, Betsy Ross, Sitting Bull, Bob Hope, Thurgood Marshall and Whitney Houston.

I don’t think there is anything wrong with honoring Americans, though I think a focus on celebrities and major figures clouds the fascinating histories of ordinary Americans. I also find it troubling that there seems to be such a concerted effort to so forcefully shape the teaching and understanding of history via threats and bullying. Yale historian Jason Stanley has written about how aspiring authoritarian governments seek to control historical narratives and discourage an exploration of the complexities of the past.

Historical scholarship requires an openness to debate and a willingness to embrace new findings and perspectives. It also involves the humility to accept that no one – least of all the government – has a monopoly on the truth.

In his executive order, Trump noted that “Museums in our Nation’s capital should be places where individuals go to learn.” I share that view. Doing so, however, means not dismantling history, but instead complicating the story – in all its messy glory.

The Conversation U.S. receives funding from the Smithsonian Institution.

Safer than Viagra

“Love Potion Number 9”(Posca on paper), by Mel Bernstine, at Bernay Fine Art, Great Barrington, Mass., through April 27.

How Main Street, Great Barrington, will look very soon.

The huge Economic Impact of New England higher Education

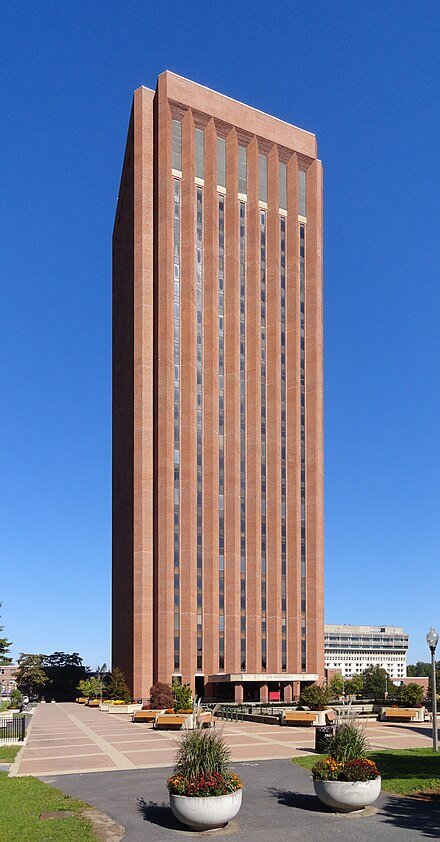

The rather ominous-looking W.E.B. Du Bois Library, at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, built in the late 1960’s, is the tallest academic research library in the world, at 26 stories.

BOSTON

Edited from a report by The New England Council (NEC) and the New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE)

These two organizations have once again partnered to release fact sheets highlighting the economic impact of the higher-education sector in the region.

These highlight the economic impact that colleges and universities have in each state, as well as aggregate data for the entire region.

Data points covered include total economic impact, federal tax revenue generated, jobs in the higher education sector, jobs created in the state, total number of institutions, total students, and students awarded a Pell Grant.

Some highlights include:

The higher education sector in New England had a total economic impact of $26.5 billion in 2024.

New England colleges and universities employed nearly 276,972 people, and served over 1.1 million students in 2024.

In New England, higher education was responsible for creating over 562,640 jobs in 2024.

Colleges and universities in New England generated $1.1 billion in federal tax revenue in 2024.

The data was compiled by NEBHE and is available to all New England Council members to use in their own advocacy efforts. You can download the fact sheets here:

For more information, please contact NEC Director of Federal Affairs Mariah Healy or NEBHE Associate Director of Policy and Research Robert Merth.

Colleen Cavanaugh: Precious offspring in my Yard

Male black swallowtail butterfly

The soft cooing of a mourning dove greets me. My eyes open as light slips between the slats of the blinds. The room brightens. The cats playfully pounce on my feet as I try to burrow deeper under the blanket. If I don’t feed them soon, their attacks will grow in ferocity, so I bound out of bed.

Throwing on my favorite jeans and a blue and white flannel shirt, I walk to the kitchen and feed Ollie and Lilly, finally appeasing their relentless mewing. As they eat, I pour a cup of steaming coffee into my to-go mug and I happily march outside to my garden.

“See you later, cats,” I call.

My coffee is hot and a little bitter, but that doesn’t matter. The sky is brightening. With a relaxed sigh, I bend over and peek at emerging seedlings. As I shamelessly congratulate myself on each garden victory, I am gleefully chattering aloud. Thankfully, only the birds can hear me. This is my spring ritual.

Later in the day, I carefully guide a young rosemary seedling into a fiery red pot, introduce a sage plant to a mustard yellow pot with green horizontal stripes, and tuck a delicate-leafed thyme into a brightly patterned blue and white checkered pot. I then sprinkle dill seeds into the soil of an old jade green pot that I found buried in a corner in my shed.

I happily arrange the haphazard pot display just outside the vegetable garden along the wooden fence. The juxtaposed colored pattern, a virtual 3-D representation of a Mondrian painting, seems to bounce and shout in the sun, beckoning the warm rays to join in a dance of photosynthesis. I am proud of my herb garden. The rosemary, sage and thyme come to life.

The dill flourishes — ethereal with its green fronds creating an intricate blanket of lace.

Over the years I have obsessively collected more pots than I needed through yard sales, gifts from friends and serendipitous purchases. Their bright colors, assurances of fertility promotion and promises of culinary conquests still seduce me.

This morning, during my habitual inspection, I spot several small, wiggling insects crawling among the dill. The closer I get and the more intensely I peer, the more green worms I see crawling. Concerned that these invaders would ravage my dill, I pluck a few out and squish them.

A day or two later at a community farm where I volunteer, I mention my new find to my friend Sheila. I often seek her help with my gardening questions.

“Sheila, I found dark green worms all over my dill this morning. I’m not sure what they are but they’re voraciously eating my dill.”

Sheila quietly shifts her focus to me from the tomatoes she is planting, raising her bushy, caterpillar-like gray eyebrows in consternation.

“Those are probably larvae of the black swallowtail butterfly,” she says matter of factly.

I am mortified but also relieved that I had not disclosed the details of my heartless killing spree to Sheila. I know this species of butterfly, whose males have exquisite black wings with small yellow and blue markings. My gardens have always been blessed with the flurry of monarchs and black swallowtails filling the sky. It’s a sight I rejoice in, and now I am saddened by my carelessness .

Returning home, I dutifully rush to the dill pot and carefully examine the remaining caterpillars. It’s as if a veil has been lifted and only now can I truly see the intricate markings of these enchanting insects. They are adorned with black, green, yellow and white horizontal stripes.

Fortunately, many are still crawling on, and chomping at, the dill. Over the next few days, I monitor them closely and am amazed at how quickly they grow but at the same time, a little saddened by how rapidly my dill is diminishing. My luscious dill is now a pot of spindly, naked stalks. Still, I feel protective of the caterpillars. I count them daily and am heartbroken when I realize their numbers are dwindling.

I diligently research the black swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes) and discover it also eats parsley. Apparently the larvae and caterpillars consume the greens of the Apiaceae family, which include carrots, dill and parsley.

And so, as the dill disappears, I gently pick up each caterpillar and transport it reverentially across the garden to my bed of parsley, placing each of them on a different parsley leaf or stem. I perform this parade of salvation many times, coaxing the caterpillars in a quiet, soothing voice, confident that I could save their population.

“Come with me, little Baxter.”

“Wait until you see what I have for you, sweet Penny.”

“Oh yes, my little Katie. You will be so happy.”

I named each of them, hoping that my silly anthropomorphic greetings will encourage their survival. I am more than eager to share my parsley with them, especially if this sacrifice could save my new friends.

However, over the next several days, the parsley remains untouched. The caterpillars continue to disappear and soon there are none.

Over the next month, the garden flourishes. Neighbors stop to comment on the beautiful allium and iris in the spring. The scent of lavender soon fills the air. Roses and clematis climb rickety trellises. I have planted many pollinators and native plants so that the bee and butterfly populations grow exponentially. rickety trellises.

In August, the dahlias start to bloom, and so there is an additional exuberance of color emerging along the driveway.

One day in early September, on a return trip from the grocery store, I notice a small black swallowtail on the driveway. I hurriedly place my grocery bags down and rush over to examine the tiny insect. It is barely moving its wings. I know it is injured. I gently pick it up and place it amongst a bed of zinnias. I can only hope that it will survive.

Later in the day, when I return to the yard to search for the butterfly. I find it motionless. Its beautiful wings lie still in the garden. I gingerly cradle its lifeless form and carry it to my study. Every day I open the small wooden jewelry box I have placed it in.

I wondered if the butterfly remembered me and had returned home to die.

Maybe it was one of the caterpillars I had transported across the yard with my silly, affectionate whispers. Maybe it was Penny or Katie. Now it is an integral part of the story of my home. Over time, its color fades, its fragile wings fall apart and one day I cannot find it.

The following spring, I plant butterfly weed, Joe Pye weed, ironweed and many other perennials I know butterflies are attracted to. In the summer, when I sit quietly in my Adirondack chair in the middle of my garden, I can see beautiful monarchs and swallowtails, hovering over flowers, drinking nectar and filling my home with their beauty. Each year the garden grows larger, colors are more vibrant and I see the gently beating wings of the precious offspring of the Baxters, Katies and Pennys from years ago.

Colleen Cavanaugh, of Bristol, R.I., is a obstetrician and gynecologist in private practice, a writer and a former ballet dancer. She recently completed her first novel, Astral Ballerinas.

Colleen Cavanaugh © 2025

‘Porous boundaries’

From Linda Leslie Brown’s show “Circulations,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through April 27.

The gallery says:

“{Boston-based} Linda Leslie Brown’s sculptures explore the transformative exchanges between nature, objects, and the viewer’s creative perception. Her works are rich with allusions to the body, while simultaneously evoking a new, transgenic nature—one where corporeal and mechanical entities merge and recombine. The sculptures suggest a world that is both fluid and uncertain, where the boundaries between organic and synthetic are porous and ever-shifting.’’

Finally, Mass. South Coast passenger trains again!

An MBTA train heads toward Boston from its New Bedford station.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The MBTA’s South Coast Rail is finally providing service between Boston, Fall River and New Bedford. As people get used to it, it will take more and more cars off the roads over the next few years and will help trigger economic development and housing construction in the two cities, which could sorely use it.

The South Coast had passenger-train service until the ‘50s, when America’s excessive dependence on cars, compounded by the start of the Interstate Highway System and a generalized government neglect of public transportation, led to its demise. Now it’s catchup.

But the $1 billion South Coast project has taken decades to get done, largely because of short-sighted nimbyism.

Consider that the construction took much longer and cost a lot more because local foes fought the most direct route, which would have involved carefully cutting through a swamp via an old rail-line route that was used until the ‘50s. Opponents cited rare turtles and salamanders. But it stretches credulity that a rail line (much narrower than a highway) would have posed much of a problem to these creatures if a proposed trestle bridge and other adjustments had been made to the swamp route to protect wildlife.

Of course, multilane roads do far, far more damage to wildlife, via vehicles running them over, air pollution, runoff from oil, gasoline and other vehicle liquids, and global warming, than trains do. And having to go in a zigzag route added 20 minutes to the South Shore to Boston trip, making it less competitive with cars.

It’s no secret that it has become outrageously easy in litigious America for small groups to block big projects for years, although they are manifestly in the general public interest. You can never please everyone. Government needs boosted eminent-domain and other powers to move faster.

xxx

Speaking of traffic, a study has confirmed what I have long suspected: Our ever-increasing traffic density can be blamed in part on the popularity in America of huge, gas-guzzling SUVs, in addition to a growing population, lousy public transit, and sprawl development.

Researchers looking at traffic in Minneapolis-St. Paul found that SUV popularity reduced the capacity of highway lanes by 9.5 percent between 1995 and 2019.

Further, while SUV drivers perceive themselves to be safer than in less, er, formidable vehicles, they are big killers of the pedestrians and people in small cars they crash into. One might also note SUV’s high profiles combined with blinding LED headlights serve to blind drivers coming from the opposite direction.

Whatever! Americans love big cars and go deep into debt to drive them. For that matter, they like big in general when they can afford it – including huge houses.

How to win and lose

“Mrs. (Isabella Stewart) Gardner in White’’ (1922), by John Singer Sargent.

“Win as though you were used to it, and lose as if you like it.’’

— Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840-1924), American art collector, philanthropist, and patroness of the arts. She founded the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, in Boston, which has a spectacular collection, though slightly less so after the world’s greatest art theft, in 1990. Its perpetrators have not been caught.

The art of data

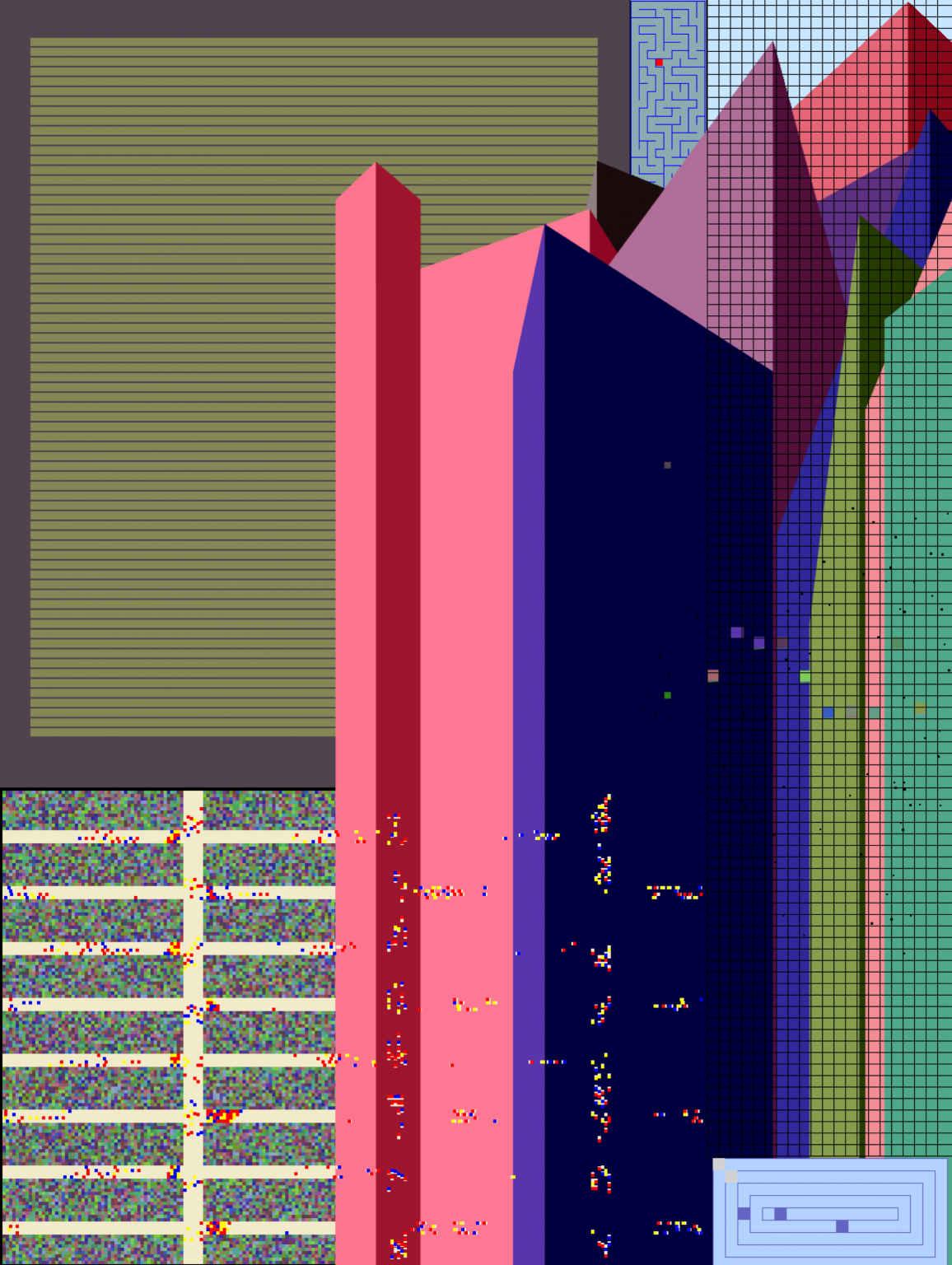

“ComplexCity” (detail), by John Simon Jr., in the group show “Data Infused,’’ at the University of Connecticut Contemporary Art Galleries, Storrs, Conn.

— Courtesy of the artist

The curator explains:

“Data Infused’’ showcases seven artists who use data as both a design material and a medium for creative expression. Moving beyond data visualization, these artists explore data's potential in artistic storytelling, transforming raw information into tangible art forms. By doing so, they reimagine data's role, emphasizing its cultural, social and artistic significance.

“The participating artists bridge traditional art practices such as drawing, printmaking, painting, sculpture, performance, and sound, with innovative digital techniques. These include custom code, algorithms, Artificial Intelligence (AI), CNC and laser etching, digital photography, and pen plotting. Their work is displayed through a wide array of media; including digital monitors, NFTs, murals, photography, sculptures, public art, and painted or printed surfaces. Data Infused will include a sampling of some of their artistic processes, offering audiences a deeper understanding of how data is transformed into unique creative outputs.’’

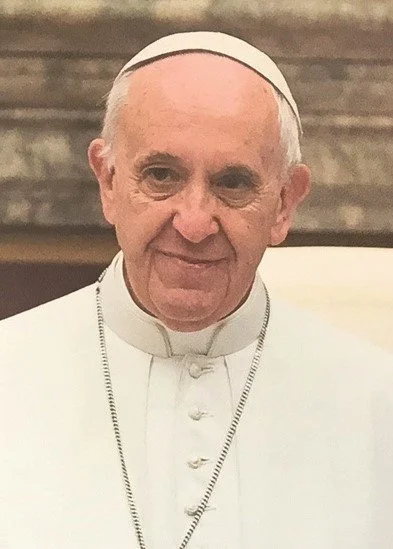

Joelle Rollo-Koster: Pope Francis has urged deep and sometimes painful engagement with History and politics

Pope Francis on April 25, 2017, when he gave a TED talk.

From The Conversation (except for image above)

Joëlle Rollo-Koster is a professor of Medieval history at the University of Rhode Island

She does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

KINGSTON, R.I.

In January 2025, while doing research at the Vatican archives, I heard Pope Francis’s Sunday prayers in St. Peter’s Square. The pope reflected on the ceasefire that had just gone into effect in Gaza, highlighting the role of mediators, the need for humanitarian aid, and his hope for a two-state solution.

“Let us pray always for tormented Ukraine, for Palestine, Israel, Myanmar, and all the populations who are suffering because of war,” he concluded. “I wish you all a good Sunday, and please, do not forget to pray for me. Enjoy your lunch, and arrivederci!”

A few weeks later, Francis was admitted to the hospital, where he remained for more than a month, receiving treatment for double pneumonia.

In those weeks of uncertainty, I thought back to the pope’s words that Sunday afternoon. They encapsulate Francis’ image: a spiritual leader using his influence to try to bring peace. He is also a down-to-earth man who wishes you “buon appetito.”

Francis does not fear addressing contemporary politics, unlike many of his predecessors. And some popes have closed their eyes to not just current events but past ones: learning and history that threatened their vision of the church.

As a medievalist, I appreciate Francis’ contrasting approach: a religious leader who embraces history and scholarship, and encourages others to do the same – even as book bans and threats to academic freedom mount.

Infamous index

For 400 years, the Catholic Church famously maintained the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, a long list of banned books. First conceived in the 1500s, it matured under Pope Paul IV. His 1559 index counted any books written by people the church deemed heretics – anyone not speaking dogma, in the widest sense.

Even before the index, church leaders permitted little flexibility of thought. In the decades leading up to it, however, the church doubled down in response to new challenges: the rapid spreading of the printing press and the Protestant Reformation.

The Catholic Counter-Reformation, which took shape at the Council of Trent from 1545-1563, reinforced dogmatism in its effort to rebuke reformers. The council decided that the Vulgate, a Latin translation of the Bible, was enough to understand scripture, and there was little need to investigate its original Greek and Hebrew version.

Bishops and the Vatican began producing lists of titles that were forbidden to print and read. Between 1571-1917, the Sacred Congregation of the Index, a special unit of the Vatican, investigated writings and compiled the lists of banned readings approved by the pope. Catholics who read titles on the Index of Forbidden Books risked excommunication.

In 1966, Pope Paul VI abolished the index. The church could no longer punish people for reading books on the list but still advised against them, as historian Paolo Sachet highlights. The moral imperative not to read them remained.

The title page of a version of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, published in 1711. National Library of Slovenia/Drw1 via Wikimedia Commons

Historian J.M de Bujanda has completed the most comprehensive list of books forbidden across the ages by the Catholic Church. Its authors include astronomer Johannes Kepler and Galileo, as well as philosophers across centuries, from Erasmus and René Descartes to feminist Simone de Beauvoir and existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre. Then there are the writers: Michel de Montaigne, Voltaire, Denis Diderot, David Hume, historian Edward Gibbon and Gustave Flaubert. In sum, the index is a who’s who of science, literature and history.

Love of humanities

Compare that with a letter Francis published on Nov. 21, 2024, emphasizing the importance of studying church history – particularly for priests, to better understand the world they live in. For the pope, history research “helps to keep ‘the flame of collective conscience’ alive.”

The pope advocated for studying church history in a way that is unfiltered and authentic, flaws included. He emphasized primary sources and urged students to ask questions. Francis criticized the view that history is mere chronology -– rote memorization that fails to analyze events.

In 2019, Francis changed the name of the Vatican Secret Archives to the Vatican Apostolic Archives. Though the archives themselves had already been open to scholars since 1881, “secret” connotes something “revealed and reserved for a few,” Francis wrote. Under Francis, the Vatican opened the archives on Pope Pius XII, allowing research on his papacy during World War II, his knowledge of the Holocaust and his general response toward Nazi Germany.

In addition to showing respect for history, the pope has emphasized his own love of reading. “Each new work we read will renew and expand our worldview,” he wrote in a letter to future priests, published July 17, 2024.

Today, he continued, “veneration” of screens, with their “toxic, superficial and violent fake news” has diverted us from literature. The pope shared his experience as a young Jesuit literature instructor in Santa Fe, then added a sentence that would have stupefied “index popes.”

“Naturally, I am not asking you to read the same things that I did,” he stated. “Everyone will find books that speak to their own lives and become authentic companions for their journey.”

Citing his Argentine compatriot, the novelist Jorge Luis Borges, Francis reminded Catholics that to read is to “listen to another person’s voice. … We must never forget how dangerous it is to stop listening to the voice of other people when they challenge us!”

When Francis dies or resigns, the Vatican will remain deeply divided between progressives and conservatives. So are modern democracies – and in many places, the modern trend leans toward nationalism, fascism and censorship.

But Francis will leave a phenomenal rebuttal. One of the pope’s greatest achievements, in my view, will have been his engagement with the humanities and humanity – with a deep understanding of the challenges it faces.

Colorful and Threatened necrophiliac

Female American Burying Beetle.

Excerpted and edited from an ecoRI News article by Frank Carini.

Series note: The region’s collection of native species is under threat on several fronts, most notably from humanity’s shortsightedness. Humans aren’t giving the natural world the space it needs and deserves. We’re crowding out non-human life, which, in turn, makes nature less productive and us less healthy. Wild New England examines the animals and insects most at risk.

The American Burying Beetle, thanks to the efforts a decade ago by third-graders at St. Michael’s Country Day School in Newport, is Rhode Island’s state insect. The students’ effort helped raise awareness about this orange-spotted insect with an interesting occupation.

After sniffing out a freshly dead animal from up to 2 miles away, the rare beetle, whose continued existence is listed as threatened, joins a mate in burying the carcass, stripping it of fur or feathers, rolling it into a ball, and covering it in oral and anal fluids to preserve it as a shelter and food source for the pair’s litter of larvae.

Nicrophorus americanus, the largest carrion beetle in North America, is native to at least 35 states and the southern borders of three eastern Canadian provinces.

When the cold rains killed the spring

— Photo by W.carter

“You expected to be sad in the fall. Part of you died each year when the leaves fell from the trees and their branches were bare against the wind and the cold, wintery light. But you knew there would always be the spring, as you knew the river would flow again after it was frozen. When the cold rains kept on and killed the spring, it was as though a young person died for no reason.”

― Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), in A Moveable Feast, his memoir of his days as a young man in Paris.

“A Rainy Day in Boston” (1885), by Childe Hassam (1859-1935).

Essence of mountain

“Cannon (Mountain) Abstract’’ (oil on canvas), by Kim Drucker Stockwell, at the Gallery at WREN, Bethlehem, N.H., in her joint show with Kristine Lingle, “Vistas and Visions,’’ through April 25.

The gallery says:

“This exhibition of northern landscapes will evoke calm, peace and contemplation.’’

Chris Powell: Political correctness flusters response to assault in school; cannibal and gambling updates

Downtown Waterbury, called “The Brass City” in its industrial heyday.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Three principles of Connecticut's political correctness have collided sensationally in Waterbury, where two middle-school students recently assaulted two other students. The victims, twin 13-year-old sisters new to the school, are of Arab descent and wore Muslim hijabs that were ripped off, so the alleged perpetrators, ages 12 and 11, are suspected of religious or ethnic prejudice. That would make the assault a “hate crime," and a political fuss is being made about it.

Children are often cruel and stupid and pick on others simply for being different. So it's just as plausible that the assault was motivated by ordinary cruelty and stupidity rather than any serious animus toward religion or ethnicity. Waterbury police are investigating and maybe they'll find out, though the public may not be told, because of those colliding principles of political correctness.

Those principles are:

1) Perpetrators of “hate crimes" should be more severely punished than perpetrators of ordinary crime because ordinary enforcement of criminal law doesn't demonstrate political correctness.

2) Short of murder, children misbehaving in school shouldn't be charged criminally or even punished at all, just referred to social workers.

3) Crime by juveniles should be handled secretly so there can never be any accountability for them or the government.

The collapse of discipline in public education argues for serious and visible punishment of students who commit assault -- something more ominous than the Waterbury middle-school principal's squishy statement about “respect, inclusivity and kindness," something requiring suspension from school and reparations to the victims.

But in the end little can be done with 11- and 12-year-olds except to watch them grow up. School authorities should be held to account but the ‘‘hate crime" crowd should can its bluster.

CANNIBAL WATCH: Questions posed by Republican state senators to the state Psychiatric Security Review Board about Tyree Smith, the murderer-cannibal whom the board recently paroled have turned out to be good ones.

In response the other week, the board's executive director, Vanessa Cardella, confirmed that despite the heavy supervision the parolee is receiving at the group home where he has been placed -- six state employees or contractors are keeping an eye on him -- he still will have plenty of time to be out and about on his own.

Cardella didn't know how much the supervisors will be paid for working on the parolee's case, but it seems likely to be many thousands of dollars a year.

Most people may not understand the necessity for the murderer-cannibal's parole and its expense. Indeed, they may be shocked and appalled. But they shouldn't blame the board, for it is only following the law, which calls for the perpetrator's release if the board thinks he'll be fine if he adheres to the conditions of his parole, which include medication.

Of course there can be no guarantee. Serious risk to the public will continue, which is why a better outcome would have been to keep the man residing in a comfortable room at the state's high-security mental hospital. This probably would be less expensive as well.

But that better outcome requires changing the law about acquittals by reason of insanity. The law simply shouldn't allow release of murderers before their old age. Republican legislators, a small minority in the General Assembly, should submit such legislation even though the Democratic majority will reject it. For at least then some Democrats may be asked to explain why people should feel good about the outcome of the murderer-cannibal's case.

THE PERFECT TAX: A recent study by the state Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services found that people addicted to gambling constitute less than 2 percent of Connecticut's population but produce more than half the state's sports betting revenue and a fifth of its revenue from all forms of gambling.

While the department sees this as a problem with a huge human cost, elected officials see it as a political solution -- the perfect tax. A tiny and disparaged minority finances a disproportionate share of state government and that human cost is not on state government's books.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

A northern visitor helps make me a fine day

A common loon in breeding plumage.

A couple of weeks ago I was sauntering along a twisting path of beach sand, through waist-high salt marsh cordgrass, on Gaspee Point, in Warwick, R.I., and passed a now vacant skeleton of an osprey platform on top of a telephone pole. Ospreys had not yet arrived here on upper Narragansett Bay, although there have been two recent osprey sightings 25 miles south, at Newport and Jamestown.

In the distance, I could see Providence’s skyline and wind turbines. Then I heard a “brrup. brrup’’ from a flock of Brandt geese swimming in sunlit shallows. Their voices would end in a higher octave and become a chorus of gabble and grunting. I wondered what they could be communicating to each other.

There were high clouds to the southwest in the otherwise cloudless blue sky. A small propeller-driven plane sounded in the distance. The wind and gently curling waves together made a whooshing noise.

A single Brandt floated near the shore, preening, while two other Brandt pushed their dark beaks into the sand and gravel bottom. They ingested tiny rounded beach stones to help digest their favorite meal, eelgrass, which they rolled into bite-size-balls before swallowing.

I saw a flash of white about 200 yards out from the beach, and quickly reached for my monocular, hoping to get a clearer view. I caught sight of him before he disappeared below the surface. I thought: “It is a solitary common loon…wow…wintering here on the bay…so lucky to see it.” I wondered where his summer home in the North Woods might be. I assumed that it was a male, but I couldn’t be certain.

In the winter, the male loons lose their elegant, “tuxedo-like” plumage, becoming a monotonous black/white. Their breeding plumage, from March to October, is a checkerboard, including a dazzling, vertical-bars, black/white “scarf.” Loons’ summer homes are pristine and remote ponds and lakes in New England’s North Woods and in Canada.*

In the winter, loons are lone visitors spread out on Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island Sound and Long Island Sound.

In the summer they make unforgettable, ethereal calls that echo off mountains, and across lakes and ponds, in the North Country. But in winter, they are silent. They are amazing swimmers with large, black web feet that let them to dive very deep, and swim long distances underwater chasing fish, their prey. Loons can be traced back to archaeopteryx in Mesozoic times. They are large birds, nearly three feet long, but clumsy flyers.

I rested my creaky, tired legs on a silver-gray, driftwood seat (about 10 feet long) with cement blocks substituting as legs. It was fairly comfortable as I scribbled in my notebook.

Then I shouted out to a friend who almost daily strolls along the shore using his bright red walking poles. He’s about 50 yards away from me, so I’m shouting, “Hey, Harry, it’s me…John…!” Harry’s retired now, and on most days walks in a five-mile loop from his house along Gaspee Point. I had last talked with him when he was raking the last autumn leaves in his yard.

Always nice to chat a bit with Harry. That, and seeing a wintering loon on our precious bay, made for a fine day.

***

*Ancient people called, among other things, Maritime Archaic People, Circumpolar People, and Lost Red Paint People, saw loons as connected to the spirit world, including the afterlife. Their territory included Demark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Latvia, the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Labrador, Newfoundland and Maine. They lived off the sea as fishermen and hunters of seals, and were skilled boat builders, navigators and tool makers. Loons fascinated such famed writers of the past as Henry David Thoreau, E.B. White, Edwin Way Teale, his wife, Nellie Teal, and the still very much alive John McPhee.

John Long is a Warwick-based writer.